A Hacker’s Dream: How the UK Could Undo Apple’s Security

Apple Says No: How the UK’s Spy Plan Could Break the Internet

TL;DR:

UK demanded Apple create a backdoor into iCloud’s Advanced Data Protection (ADP) encryption in January 2025, aiming to access all user data globally under the Investigatory Powers Act, sparking a privacy vs. security debate.

Potential abuses include cybersecurity risks (e.g., exploitation by hackers like in the Salt Typhoon breach), scope creep into mass surveillance, erosion of trust in Apple, and threats to human rights, as ruled by the European Court in Podchasov v. Russia.

Privacy advocates argue encryption protects against cyberattacks, while the UK claims it hampers crime investigations; experts say no “safe” backdoor exists, suggesting targeted alternatives like metadata analysis.

Apple, a $3.5 trillion private entity, disabled ADP in the UK on February 21, 2025, prioritizing global user security over compliance, clashing with government expectations and risking industry precedent for firms like Google and Meta.

Geopolitically, it strains US-UK Five Eyes ties, sets a precedent for nations like China, damages the UK’s tech reputation, and weakens cybersecurity amid rising threats, with the US and Apple pushing back via legislation and defiance.

And now for the Deep Dive…

Introduction

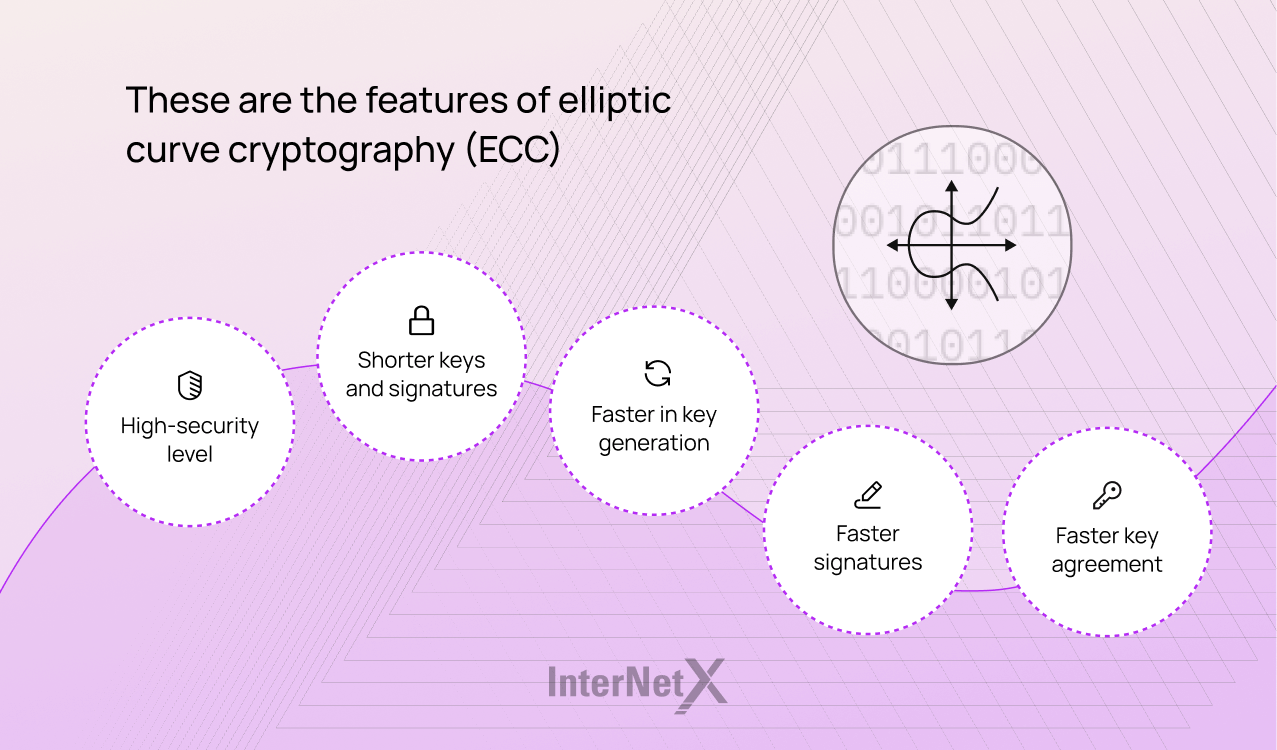

In a revelation that has sent shockwaves through the tech world, the United Kingdom’s Home Office issued a clandestine directive in January 2025, demanding that Apple dismantle the end-to-end encryption safeguarding its iCloud Advanced Data Protection (ADP) service—a feature that ensures only the user holds the cryptographic keys to their data, rendering it inaccessible even to Apple itself. This isn’t a targeted request for specific accounts tied to criminal investigations; it’s a blanket order, compelling Apple to engineer a systemic backdoor that would expose the encrypted backups, photos, and notes of over a billion users worldwide, far beyond the UK’s jurisdiction. Encryption, the mathematical bedrock of digital security, leverages complex algorithms like AES-256 and elliptic curve cryptography (ECC) to transform plaintext into ciphertext, ensuring that intercepted data remains unintelligible without the corresponding private key. This technology underpins everything from secure messaging to financial transactions, making it a cornerstone of modern privacy. The UK’s move, shrouded in secrecy under a gag order from the Investigatory Powers Act (IPA) of 2016, has thrust the perennial clash between individual privacy and governmental oversight into a new, volatile spotlight, with Apple and the United States vociferously resisting a demand that could fracture global trust in digital ecosystems.

The potential for abuse inherent in this backdoor is staggering, rooted in both technical vulnerabilities and human overreach. Cybersecurity experts warn that introducing a deliberate weakness into Apple’s encryption—say, by embedding a master key or a key escrow system—creates an exploitable flaw that transcends the UK’s stated intent of combating terrorism and child exploitation. Such a backdoor, even if initially controlled by a trusted authority, could be reverse-engineered or stolen, as evidenced by the 2024 Salt Typhoon breaches, where Chinese hackers exploited court-mandated telecom backdoors to surveil U.S. targets, including the FBI. The technical reality is unforgiving: encryption is a binary proposition—either it’s secure for all or vulnerable to all. A backdoor could enable mass decryption of iCloud data, exposing everything from personal photos to corporate secrets, and historical precedents like the NSA’s PRISM program, revealed by Edward Snowden, suggest that scope creep is inevitable once such capabilities exist. Beyond state actors, rogue hackers or authoritarian regimes could weaponize this flaw, endangering activists and journalists who rely on ADP’s security, a concern underscored by the European Court of Human Rights’ 2024 ruling in Podchasov v. Russia, which deemed encryption weakening a violation of privacy rights.

This demand pits privacy against national security in a way that defies easy resolution, while simultaneously dragging private enterprise into a quagmire of public safety obligations. The UK justifies its stance with the “going dark” argument—law enforcement’s oft-cited lament that end-to-end encryption, which uses protocols like Diffie-Hellman key exchange to establish secure channels, blinds them to critical evidence in serious crimes. Yet, cryptographers counter that no backdoor can be “safe”: any mechanism granting government access—perhaps a split-key system where the Home Office holds one half—introduces a single point of failure that undermines the entire security architecture. Apple, a private entity with a $3.5 trillion market cap, has built its brand on privacy, embedding features like Secure Enclave and hardware-backed key derivation to protect user data. The IPA’s Technical Capability Notice, however, asserts extraterritorial authority, demanding Apple reengineer its global systems, a clash that pits corporate autonomy against state power. Rather than comply, Apple disabled ADP for UK users on February 21, 2025, a move that preserves its principles but leaves British customers exposed, highlighting the irreconcilable tension between a company’s duty to its users and a government’s claim to public safety—an impasse with no middle ground.

Geopolitically, the UK’s gambit threatens to unravel alliances and ignite a cascade of consequences. The U.S., a Five Eyes partner, has reacted with fury, with lawmakers like Senator Ron Wyden and Representative Andy Biggs decrying the order as a “foreign cyberattack” that jeopardizes American data security. On February 26, 2025, Director of National Intelligence Tulsi Gabbard called it a “clear and egregious violation” of privacy, hinting at retaliatory limits on intelligence-sharing under the CLOUD Act. The technical ripple effect is equally dire: if Apple capitulates, nations like China or Russia could demand identical access, leveraging the IPA’s precedent to pierce ADP’s 256-bit symmetric keys and ECC-based protections, potentially forcing Apple to exit markets entirely. The UK’s tech reputation is at stake too—experts like Signal’s Meredith Whittaker warn it risks becoming a “pariah” as firms like Google and Meta, who’ve resisted similar pressures, watch closely. Amid escalating cyber threats—think Salt Typhoon’s telecom incursions—the U.S. Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA) doubled down on end-to-end encryption in December 2024, amplifying the stakes. Apple’s defiance, met with U.S. legislative moves like Wyden’s draft bill to curb foreign encryption demands, signals a brewing transatlantic rift that could redefine digital sovereignty and security for decades.

Background: The UK’s Demand and Apple’s Encryption

The United Kingdom’s push to undermine Apple’s encryption infrastructure began in earnest with a covert order issued in January 2025 under the Investigatory Powers Act (IPA) of 2016, a legislative framework granting authorities sweeping surveillance powers, including the issuance of Technical Capability Notices that mandate tech firms to decrypt data on demand. This specific directive, revealed by The Guardian on February 7, 2025, doesn’t target individual suspects but instead demands unrestricted access to all iCloud data protected by Apple’s Advanced Data Protection (ADP) feature—a mechanism rolled out in 2022 to extend end-to-end encryption to backups, photos, and notes, covering roughly 90% of a user’s iCloud content. Unlike narrower warrants, this order’s global scope threatens the security of over a billion Apple users, from London to Los Angeles, by requiring a systemic alteration to ADP’s cryptographic architecture, which relies on 256-bit AES keys and elliptic curve cryptography (ECC) for key derivation. Compounding the audacity, a gag order under Section 87 of the IPA forbids Apple from publicly acknowledging the demand, shrouding it in secrecy until leaks forced it into the open, sparking outrage over its extraterritorial overreach and technical implications.

Apple’s encryption framework, particularly ADP, represents a pinnacle of cryptographic engineering designed to thwart unauthorized access—even by Apple itself. At its core, end-to-end encryption ensures that data is encrypted on the user’s device with a private key stored in the Secure Enclave, a dedicated hardware subsystem using a tamper-resistant ARM coprocessor to manage cryptographic operations like key generation via the Elliptic Curve Integrated Encryption Scheme (ECIES). When ADP is enabled, iCloud data is encrypted with a unique 256-bit AES key, itself encrypted with the user’s private key, which Apple cannot access; this ciphertext is then synced to Apple’s servers, indecipherable without the user’s device-specific credentials. The company has long championed privacy as a “fundamental human right,” a stance crystallized in its 2016 refusal to unlock an iPhone for the FBI in the San Bernardino case, where it argued that creating a backdoor—essentially a software bypass to brute-force the device’s 10,000-iteration PBKDF2-derived passcode—would endanger all users. That defiance set a precedent Apple now invokes, with CEO Tim Cook reiterating in a February 2025 statement to The Washington Post that any weakening of ADP’s protections would be a “grave disappointment” to its user base, reflecting a corporate ethos rooted in technical integrity over governmental compliance.

The timing of the UK’s demand aligns with a crescendo of cyber threats that have rattled global security, most notably the Salt Typhoon campaign, a Chinese state-sponsored operation that infiltrated U.S. telecom networks in late 2024, exploiting court-mandated backdoors to harvest call records and metadata from thousands of targets, including lawmakers and FBI agents. Reported by Ars Technica on February 7, 2025, this breach underscored the fragility of systems compromised for law enforcement access, amplifying the UK’s urgency to pierce Apple’s defenses amid fears of similar vulnerabilities going unaddressed. The Home Office justifies its order by arguing that end-to-end encryption creates a “black box” for investigators, obstructing efforts to track terrorists plotting via iMessage or pedophiles sharing files through iCloud—a position echoing the FBI’s “going dark” rhetoric. Yet, this justification hinges on a shaky premise: that Apple can selectively unlock ADP without dismantling its security wholesale, a notion cryptographers dismantle by pointing to the indivisible nature of symmetric-key systems, where a single compromised key unravels the entire chain of trust.

The technical infeasibility of the UK’s demand lies in the architecture of ADP itself, which eschews centralized key escrow—where a third party holds decryption keys—in favor of a decentralized model where only the user’s device can perform the necessary cryptographic handshake. Implementing a backdoor might require Apple to rewrite iOS and macOS to insert a secondary keypair, perhaps using a government-held public key to encrypt a duplicate of the user’s private key, which could then be decrypted by authorities with the corresponding private key. Such a scheme, however, introduces a catastrophic single point of failure: if that government key is leaked—whether through hacking, insider threats, or coercion—the entire ADP ecosystem collapses, exposing data globally. The Electronic Frontier Foundation warned on February 21, 2025, that this isn’t hypothetical; historical breaches like the 2013 NSA key compromise via contractor leaks demonstrate the peril. Apple’s response—disabling ADP for UK users rather than complying—sidesteps this trap but leaves British customers reliant on standard iCloud encryption, which Apple can decrypt, illustrating the stark trade-off between compliance and security.

The UK’s gambit also reflects a broader geopolitical calculus, leveraging its Five Eyes intelligence partnership to assert dominance in a digital arms race where encryption is both shield and sword. The order’s timing, post-Salt Typhoon, suggests a panicked bid to preempt cyber threats, yet it risks alienating allies like the U.S., where lawmakers view it as a sovereignty violation, per The Washington Post’s February 13 coverage. The BBC noted on February 7 that the Home Office frames this as a national security imperative, citing cases where encrypted data stalled investigations into child exploitation networks—a visceral appeal to public safety. But the technical reality undermines this narrative: ADP’s use of per-device key derivation and hardware-backed entropy (via the Secure Enclave’s TRNG) means no universal unlock exists without rewriting the system from the ground up, a process Apple deems infeasible without betraying its global user base. This standoff, rooted in the clash between IPA’s legal muscle and ADP’s cryptographic rigor, sets the stage for a showdown with far-reaching implications, as Apple digs in and the UK doubles down.

Potential Abuses of an Encryption Backdoor

The introduction of an encryption backdoor, as demanded by the UK government from Apple in January 2025, carries profound cybersecurity risks that extend far beyond its intended use. Such a backdoor—potentially implemented as a secondary keypair embedded within Apple’s Advanced Data Protection (ADP) framework—would fundamentally weaken the 256-bit AES encryption and elliptic curve cryptography (ECC) that safeguard iCloud data, creating an exploitable vulnerability ripe for abuse by hackers, cybercriminals, and hostile nation-states. The technical reality is stark: any mechanism allowing government access, such as a split-key system where the UK Home Office holds a decryption key, introduces a single point of failure that could be targeted through sophisticated attacks like side-channel cryptanalysis or social engineering to extract key material. A chilling real-world example emerged in late 2024 with the Salt Typhoon breach, where Chinese state-sponsored hackers infiltrated U.S. telecom networks, exploiting court-mandated backdoors to harvest call records and metadata from thousands, including FBI agents, as reported by Bank Info Security on February 6, 2025. This incident illustrates how backdoors, once created, become magnets for exploitation, undermining not just individual privacy but entire systems—a risk Apple’s refusal to comply seeks to avert.

Beyond immediate cybersecurity threats, the UK’s backdoor mandate opens the door to scope creep, where a tool designed for targeted investigations morphs into a mechanism for mass surveillance, echoing historical abuses by intelligence agencies. The UK’s Investigatory Powers Act (IPA) Technical Capability Notice demands blanket access to ADP-encrypted data, not merely assistance with specific accounts—an unprecedented escalation that could enable real-time decryption of all iCloud traffic if paired with automated key retrieval systems. Cryptographers warn that such capabilities, once integrated into Apple’s servers, could be repurposed for widespread monitoring, leveraging techniques like deep packet inspection to flag and decrypt communications en masse. The Snowden leaks of 2013, detailed by The Guardian on September 6, 2013, provide a sobering parallel: the NSA and GCHQ covertly inserted backdoors into commercial encryption software, siphoning off vast troves of personal data under programs like PRISM, far exceeding their legal mandates. This slippery slope suggests that the UK’s current justification—combating terrorism and child exploitation—could easily expand into routine surveillance of ordinary citizens, a prospect made more feasible by the IPA’s extraterritorial reach.

The erosion of trust in Apple and the broader tech ecosystem is another inevitable casualty of an encryption backdoor, with ripple effects that could destabilize consumer confidence and empower authoritarian regimes. Apple’s ADP relies on a hardware-backed Secure Enclave to generate and store private keys, ensuring that even the company cannot access user data—a promise that has bolstered its reputation as a privacy-centric brand, as noted in its February 7, 2025, response to The Washington Post. Introducing a backdoor would shatter this trust, signaling to users that their iPhones and iPads—secured by a 10,000-iteration PBKDF2 passcode derivation—are no longer impregnable, potentially driving them to less secure alternatives. Worse, the precedent set by the UK could embolden nations like China and Russia to demand reciprocal access, as highlighted by Amnesty International on February 14, 2025. These regimes could exploit the same backdoor—perhaps by coercing Apple to hand over the UK’s decryption key or replicating the exploit—to target dissidents, a scenario where a single leaked key could decrypt billions of files globally, amplifying the damage far beyond Britain’s borders.

Human rights concerns further underscore the backdoor’s perils, particularly for activists, journalists, and dissidents who depend on encrypted communication to evade persecution. ADP’s end-to-end encryption, using Diffie-Hellman key exchange to establish secure channels, is a lifeline for these groups, ensuring that intercepted data remains ciphertext without the user’s private key, stored securely in the Secure Enclave. A backdoor, however, would expose this data—imagine a journalist’s source list or an activist’s protest plans—laying bare vulnerabilities that authoritarian governments could exploit, as Human Rights Watch warned on February 14, 2025. The European Court of Human Rights’ landmark ruling in Podchasov v. Russia, reported by the Electronic Frontier Foundation on March 5, 2024, explicitly condemned encryption weakening as a violation of Article 8 privacy rights, arguing that backdoors enable “general and indiscriminate surveillance” by compromising all users’ security. The UK’s demand directly contravenes this precedent, threatening the very populations encryption was designed to protect.

Finally, the technical and ethical fallout from a backdoor transcends national boundaries, intertwining cybersecurity, trust, and human rights into a single, precarious knot. Implementing the UK’s request might involve Apple deploying a firmware update to silently install a government-accessible key, perhaps using a zero-knowledge proof to mask its presence—an endeavor that, while theoretically possible, would be detectable by security researchers, as Wired speculated on February 10, 2025. Once exposed, the backlash could cripple Apple’s $3.5 trillion market cap and spark a exodus from iCloud, while simultaneously handing authoritarian regimes a blueprint to replicate the exploit. The Salt Typhoon breach already demonstrated how backdoors amplify state-sponsored hacking; coupling this with GCHQ’s history of mass interception, per The Guardian’s 2018 report, paints a dystopian future where privacy is a relic. The UK’s push, far from a surgical tool, risks unleashing a global cascade of abuse, where the only winners are those who thrive on insecurity.

Privacy vs. National Security: A Perennial Tension

The UK government’s case for compelling Apple to introduce an encryption backdoor hinges on a national security argument that portrays end-to-end encryption as an impenetrable barrier to law enforcement, stymieing investigations into terrorism, child exploitation, and organized crime. As articulated by the Home Office in a statement reported by The Guardian on February 7, 2025, the Advanced Data Protection (ADP) feature—encrypting iCloud data with 256-bit AES keys derived via elliptic curve cryptography (ECC) and stored in the Secure Enclave—renders critical evidence inaccessible, even under lawful warrants issued pursuant to the Investigatory Powers Act (IPA). This argument aligns with the “going dark” narrative long championed by the FBI, which contends that modern cryptographic protocols like Diffie-Hellman key exchange and per-device key derivation create a digital black box, thwarting real-time interception of communications or retrospective decryption of stored data. UK officials point to specific cases—such as encrypted iMessage threads linked to terror plots or iCloud-hosted child abuse imagery—where the lack of a master key or backdoor has stalled prosecutions, framing Apple’s refusal to comply as a direct threat to public safety in an era of escalating cyber-enabled crime.

In stark opposition, privacy advocates and Apple itself assert that encryption is not a luxury but a vital shield against both cyberattacks and government overreach, preserving a digital ecosystem where users retain sovereignty over their data. ADP’s architecture, which encrypts data on-device using a hardware-backed random number generator (TRNG) within the Secure Enclave to seed unique keys, ensures that even Apple cannot access user backups—a design hailed by the Electronic Frontier Foundation on February 21, 2025, as a bulwark against breaches like the Salt Typhoon hack that exploited telecom backdoors in 2024. This protection extends beyond personal convenience to societal resilience: without robust encryption, sensitive data—from medical records to corporate IP—becomes low-hanging fruit for state-sponsored hackers or rogue actors, as evidenced by China’s infiltration of U.S. networks. Privacy proponents argue that backdoors, far from enhancing safety, erode a fundamental right enshrined in rulings like the European Court of Human Rights’ Podchasov v. Russia decision, weakening public security by exposing all users to the same vulnerabilities that law enforcement seeks to exploit, a point Apple underscored when it disabled ADP for UK users rather than comply.

The tension between these poles often frames privacy and national security as a zero-sum game, but cryptographers and security experts dismantle this as a false dichotomy, asserting that no backdoor can be engineered without jeopardizing the entire system. Introducing a government-accessible key—say, a secondary ECC public key paired with a private key held by the Home Office—requires rewriting ADP’s key management, likely embedding a firmware-level bypass that could decrypt the AES-256 ciphertext protecting iCloud data. Yet, as Johns Hopkins cryptologist Matthew Green told Wired on February 10, 2025, this isn’t a “magic wand” solution: any such weakness, once introduced, becomes a universal exploit, vulnerable to reverse-engineering or theft via attacks like differential power analysis on the Secure Enclave. The Salt Typhoon breach, detailed by Bank Info Security on February 6, 2025, proves this risk isn’t theoretical—hackers exploited similar backdoors to devastating effect. The expert consensus is unambiguous: encryption’s strength lies in its uniformity; puncturing it for one compromises all, a reality that renders the UK’s demand technically untenable.

Alternative solutions exist that sidestep this cryptographic conundrum, offering law enforcement viable paths to intelligence without shattering encryption’s foundations. Techniques like metadata analysis—examining call logs, geolocation, or IP traffic preserved outside ADP’s encrypted scope—can map criminal networks without decrypting content, a method the FBI has leveraged successfully in past cases, per The Washington Post’s February 13, 2025, coverage of U.S. lawmakers’ rebuttals to the UK order. Device forensics, too, can extract plaintext from seized iPhones using physical access to bypass lock screens via tools like Cellebrite’s UFED, without requiring Apple to rewrite iOS or embed a backdoor—a process Ars Technica noted on February 7, 2025, as a proven workaround. These targeted approaches, bolstered by international cooperation under frameworks like the CLOUD Act, preserve encryption’s integrity while addressing the “going dark” challenge, yet the UK’s blanket demand eschews such nuance, prioritizing immediate access over long-term security.

This standoff encapsulates a perennial tension that defies resolution through technical compromise, forcing a reckoning over values as much as mechanisms. Privacy advocates, including Privacy International in a February 12, 2025, statement, warn that backdoors don’t just undermine rights but invite abuse, echoing the NSA’s PRISM overreach revealed in 2013—a program that hoovered up data far beyond its mandate. Conversely, the UK’s insistence, backed by real threats like those uncovered in encrypted terror plots, carries visceral weight, yet its solution risks amplifying the very cyber vulnerabilities it aims to combat, as CISA’s December 2024 guidance on end-to-end encryption emphasized. Apple’s defiance—rooted in the impossibility of a “safe” backdoor and the global stakes of its $3.5 trillion ecosystem—casts the debate as a litmus test for digital governance, where the choice between privacy and security may prove illusory if neither can be assured in a weakened system.

Private Enterprise vs. Public Safety: Whose Responsibility?

Apple’s stance as a private entity in the face of the UK’s January 2025 demand to unlock its Advanced Data Protection (ADP) encryption underscores a resolute commitment to user trust and product integrity, prioritizing these over compliance with governmental edicts. ADP, introduced in 2022, extends end-to-end encryption to iCloud data using 256-bit AES keys paired with elliptic curve cryptography (ECC) for key derivation, all managed by the Secure Enclave—a hardware subsystem that ensures Apple itself cannot decrypt user backups, photos, or notes. This design, as Apple reiterated in a statement to The Washington Post on February 7, 2025, reflects a deliberate choice to embed privacy as a “fundamental human right” into its ecosystem, a principle that has fueled its defiance since the 2016 San Bernardino case, where it refused to bypass an iPhone’s 10,000-iteration PBKDF2 passcode. With a $3.5 trillion market cap and a global brand synonymous with security, Apple’s economic stakes amplify this resolve—any backdoor, such as a firmware-injected secondary keypair, risks alienating a user base that expects its devices to remain impregnable, a trust that underpins its dominance in the tech market.

In contrast, the UK government leverages the Investigatory Powers Act (IPA) of 2016 to assert that private enterprises like Apple bear a public safety responsibility, mandating technical assistance to law enforcement through mechanisms like Technical Capability Notices. The IPA’s Section 255 empowers authorities to compel firms to decrypt data or render it “intelligible,” a requirement the Home Office argues is critical to pierce ADP’s encryption and access evidence in investigations ranging from terrorism to child exploitation, as detailed by The Guardian on February 7, 2025. This public safety narrative casts tech giants as indispensable partners in crime prevention, a view bolstered by the “going dark” problem—where protocols like Diffie-Hellman key exchange thwart lawful intercepts. The UK envisions a system where Apple might integrate a government-held decryption key into its servers, enabling real-time access to iCloud ciphertext, yet this expectation clashes with the technical reality that such a key would require a complete overhaul of Apple’s decentralized encryption model, exposing a fundamental disconnect between state authority and corporate architecture.

The clash of interests crystallized when Apple, rather than acquiescing, disabled ADP for UK users on February 21, 2025, a move reported by the Electronic Frontier Foundation that preserved its global security standards while leaving British customers reliant on standard iCloud encryption—decryptable by Apple under warrant. This decision reflects a deeper tension between corporate autonomy and state power: Apple contends that rewriting iOS to embed a backdoor—perhaps via a Secure Enclave firmware update delivering a UK-accessible ECC public key—would compromise all users, not just those in the UK, a stance rooted in the indivisible nature of cryptographic trust. The IPA’s extraterritorial scope, however, asserts jurisdiction over Apple’s U.S.-based operations, raising the question of where the line should be drawn. Does a private entity’s duty to its shareholders and customers outweigh a government’s claim to public safety, especially when compliance could unleash a cascade of vulnerabilities, as seen in the Salt Typhoon telecom breaches of 2024? Apple’s refusal suggests it prioritizes its sovereign design choices over yielding to a foreign mandate, a defiance that tests the limits of state coercion.

The broader implications for the tech industry loom large, as the UK’s precedent-setting demand threatens to ensnare other giants like Google and Meta in a web of similar obligations. Google’s Encrypted Client Hello (ECH) and Meta’s WhatsApp, both reliant on end-to-end encryption using protocols like TLS 1.3 and Signal’s double-ratchet algorithm, could face parallel Technical Capability Notices, forcing a reckoning over whether privacy features remain viable, as Ars Technica speculated on February 7, 2025. A successful UK push could normalize backdoors—imagine Google embedding a key escrow system in Android’s SafetyNet or Meta altering WhatsApp’s X3DH key exchange—eroding the competitive edge of secure ecosystems. Privacy International warned on February 12, 2025, that this precedent would embolden authoritarian regimes to demand equivalent access, amplifying global risks. Apple’s $3.5 trillion valuation and its peers’ market heft mean that caving to the UK could shift industry norms, compelling firms to weigh compliance costs against the loss of user trust—an economic and ethical bind.

Perhaps most critically, the UK’s demand risks a chilling effect on innovation in secure technologies, stifling the development of next-generation encryption that companies like Apple rely on to counter escalating cyber threats. The creation of ADP itself—integrating hardware-backed entropy from the Secure Enclave’s TRNG with cloud-based encryption—was a response to breaches like the 2014 iCloud hack, a trajectory Bank Info Security highlighted on February 6, 2025, as evidence of tech’s proactive security evolution. If backdoors become standard, engineers may hesitate to deploy advanced systems—say, quantum-resistant algorithms like lattice-based cryptography—fearing mandated weaknesses, as CISA’s December 2024 guidance urged against. Wired noted on February 10, 2025, that Apple’s disablement of ADP in the UK signals a retreat from innovation under pressure, a cautionary tale for an industry where security is both a selling point and a survival strategy. This clash, then, isn’t just about Apple versus the UK—it’s about who ultimately shapes the future of digital safety: private enterprise or public authority.

(Pictured above: Diffie-Hellman key exchange)

Geopolitical Impact: A Global Domino Effect

The geopolitical ramifications of the UK’s January 2025 demand that Apple install a backdoor into its Advanced Data Protection (ADP) encryption system reverberate far beyond its borders, placing immediate strain on the historically robust US-UK relationship, particularly within the Five Eyes intelligence-sharing alliance. This alliance, comprising the US, UK, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand, relies on seamless cooperation under agreements like the CLOUD Act, which facilitates cross-border data access for law enforcement while preserving encryption standards. However, the UK’s secret Technical Capability Notice, issued under the Investigatory Powers Act (IPA) and exposed by The Washington Post on February 7, 2025, has provoked a fierce backlash from US lawmakers, with Senator Ron Wyden and Representative Andy Biggs labeling it a “foreign cyberattack waged through political means.” In a letter to Director of National Intelligence Tulsi Gabbard, reported by Computer Weekly on February 13, 2025, they urged a reevaluation of intelligence-sharing and cybersecurity cooperation, threatening retaliatory measures such as restricting the UK’s access to Five Eyes resources. This rift stems from the technical reality that a backdoor—potentially a government-held ECC private key embedded in ADP’s 256-bit AES framework—would expose American users’ data, undermining trust in a cornerstone of transatlantic security collaboration.

Beyond bilateral tensions, the UK’s move sets a perilous global precedent, inviting a domino effect where other nations, notably China and India, could demand equivalent access to Apple’s encrypted systems, further eroding international encryption standards and igniting debates over digital sovereignty. If Apple were to comply, it might integrate a key escrow system or firmware update to bypass the Secure Enclave’s hardware-backed key derivation, a change that would be universal, not UK-specific, due to the indivisible nature of end-to-end encryption. Human Rights Watch warned on February 14, 2025, that authoritarian regimes could exploit this precedent, leveraging their own surveillance laws—China’s Cybersecurity Law or India’s IT Act—to coerce Apple into decrypting iCloud data, potentially exposing billions of files globally. This would weaken standards like TLS 1.3 or the Signal Protocol, which rely on uncompromised cryptography, and fuel a race to the bottom in digital sovereignty, where nations assert control over tech firms at the expense of universal security. The Guardian noted on February 26, 2025, that such demands could fragment the internet, pitting national interests against a cohesive global digital framework.

Economically, the UK risks tarnishing its reputation as a tech leader, sliding toward what Signal president Meredith Whittaker called a “pariah” status in a February 2025 critique cited by Privacy International. The IPA’s extraterritorial reach, compelling Apple to alter its global ADP infrastructure, could drive the company to withdraw critical features—or even its entire market presence—from the UK, a scenario Apple hinted at in its March 2024 parliamentary submission, per The Guardian on February 7, 2025. This withdrawal, already partially realized with ADP’s disablement for UK users on February 21, 2025, as reported by the Electronic Frontier Foundation, would deal a blow to consumers reliant on Apple’s ecosystem and to the UK economy, which touts tech innovation as a growth engine. A broader exodus by tech giants like Google or Meta, facing similar pressures, could shrink the UK’s digital market, costing jobs and investment while boosting competitors like the EU or US, where encryption protections remain stronger—an outcome that contrasts sharply with the UK’s post-Brexit tech ambitions.

The cybersecurity landscape faces an equally dire shift, with the UK’s backdoor demand amplifying vulnerabilities to state-sponsored hacks amid rising geopolitical tensions, exemplified by China’s Salt Typhoon breaches of US telecoms in 2024. Those attacks, detailed by Bank Info Security on February 6, 2025, exploited existing backdoors to harvest metadata and calls, a preview of what could unfold if ADP’s encryption—secured by per-device keys and Secure Enclave entropy—is pierced. A UK-mandated backdoor, perhaps a reverse proxy like the FRP clients used in Volt Typhoon campaigns (noted by CISA on February 6, 2024), could become a target for actors like China’s APT groups, who could decrypt iCloud data en masse, escalating risks to critical infrastructure and private citizens alike. CISA’s December 2024 guidance, urging end-to-end encryption adoption, stands in direct opposition, advocating stronger defenses as a countermeasure—a stance the UK’s policy undermines, potentially leaving allied nations more exposed in an already fraught cyberwar.

This confluence of geopolitical, economic, and cybersecurity fallout underscores a broader domino effect that could reshape the global digital order. The US’s pushback, including Wyden’s draft bill to reform the CLOUD Act, reported by Nextgov/FCW on February 14, 2025, signals a pivot toward encryption preservation, potentially isolating the UK within Five Eyes and beyond. Meanwhile, Apple’s market withdrawal threats, if realized, could cascade to other regions under similar pressure, disrupting economies and consumer access worldwide. The weakening of encryption standards might also stifle innovation, as firms hesitate to deploy advanced systems like lattice-based cryptography, fearing mandated flaws. Wired’s February 10, 2025, analysis warns of a fractured tech landscape—one where the UK’s short-term surveillance gains could precipitate long-term losses in trust, security, and global standing, handing adversaries a strategic advantage in an increasingly contested digital domain.

Reactions: Apple and the US Strike Back

Apple’s response to the UK’s January 2025 demand to install a backdoor into its Advanced Data Protection (ADP) encryption system was swift and uncompromising, reflecting both technical pragmatism and a steadfast commitment to user security. On February 21, 2025, Apple disabled ADP for all UK users, as reported by the Electronic Frontier Foundation, effectively rolling back the end-to-end encryption that safeguards iCloud data with 256-bit AES keys and elliptic curve cryptography (ECC) managed by the Secure Enclave—a move that reverted British customers to standard iCloud encryption, which Apple can decrypt under legal compulsion. Publicly, the company expressed being “gravely disappointed” with the UK’s secret Technical Capability Notice, issued under the Investigatory Powers Act (IPA), yet remained resolute, with CEO Tim Cook telling The Washington Post on February 7, 2025, that building a backdoor—such as a firmware-injected secondary keypair—was “not something we can do” without undermining global user trust. This strategic retreat prioritizes the integrity of Apple’s worldwide ecosystem over compliance with a single market, preserving the cryptographic sanctity of ADP’s decentralized key management for its billion-plus users outside the UK, even at the cost of alienating British consumers.

The US government’s reaction was equally forceful, marked by bipartisan outrage and a swift escalation that underscored the transatlantic stakes of the UK’s overreach. Senators Ron Wyden (D-OR) and Representative Andy Biggs (R-AZ) issued a scathing rebuke, demanding the UK retract the order, which they branded a “foreign cyberattack” on American privacy in a letter to Director of National Intelligence (DNI) Tulsi Gabbard, covered by Computer Weekly on February 13, 2025. Gabbard herself condemned the demand as a “clear and egregious violation” of Americans’ rights during a February 26, 2025, briefing reported by The Guardian, highlighting how a backdoor—potentially a government-held ECC private key—could expose US citizens’ iCloud data to foreign surveillance, breaching the CLOUD Act’s spirit. Wyden doubled down with legislative action, drafting a bill to amend the CLOUD Act, detailed by Nextgov/FCW on February 14, 2025, which would bar foreign governments from compelling US firms to weaken encryption, aiming to fortify legal protections against such extraterritorial mandates—a direct counterstrike to safeguard the Secure Enclave’s hardware-backed entropy and ADP’s per-device key derivation from global compromise.

Public and expert sentiment amplified this resistance, with privacy advocates decrying the UK’s move as a historic assault on digital rights. The Electronic Frontier Foundation labeled it an “unprecedented attack” on February 21, 2025, arguing that any backdoor—say, a split-key system integrated into iOS—would unravel the end-to-end encryption that protects activists and journalists worldwide, a concern echoed by Privacy International’s Meredith Whittaker, who warned of a “global privacy catastrophe” on February 12, 2025. Cybersecurity experts piled on, with Alan Woodward of Surrey University telling The Telegraph on February 13, 2025, that the “unintended consequences” of a backdoor could be catastrophic—imagine a leaked key enabling mass decryption of iCloud ciphertext, a scenario akin to the Salt Typhoon breaches of 2024. This chorus of dissent reflects a technical consensus: encryption’s strength is absolute or it’s nothing; weakening it for the UK’s IPA risks a cascade of exploits that no firmware patch or zero-knowledge proof could contain, threatening the very fabric of digital security.

Apple’s technical defiance and the US’s political pushback signal a broader strategic alignment aimed at preserving encryption’s global integrity over yielding to localized pressure. By disabling ADP rather than rewriting its architecture—potentially embedding a UK-accessible decryption key into the Secure Enclave’s TRNG-seeded keychain—Apple sidestepped a universal vulnerability that could have been exploited by adversaries like China or Russia, a risk Human Rights Watch flagged on February 14, 2025, as a boon to authoritarian surveillance. The US response, blending legislative threats with DNI condemnation, leverages its Five Eyes clout to deter the UK, hinting at reduced intelligence-sharing if the order persists—a geopolitical flex rooted in the CLOUD Act’s transatlantic framework. This dual resistance underscores a shared recognition: a backdoor’s technical footprint, once created, transcends borders, inviting a flood of copycat demands that could dismantle the cryptographic trust underpinning modern tech ecosystems.

The interplay of these reactions paints a high-stakes standoff with ramifications beyond the UK-US axis, challenging the balance of power in global tech governance. Cybersecurity expert Bruce Schneier, cited by Wired on February 10, 2025, warned that the UK’s demand could “break the internet’s security model,” as a compromised ADP—say, via a reverse-engineered key escrow—would weaken standards like TLS 1.3 or Signal’s double-ratchet, emboldening state-sponsored hackers already emboldened by breaches like Salt Typhoon. Apple’s retreat from ADP in the UK, while a tactical loss, preserves its long-term credibility, aligning with the US’s legislative salvo to shield encryption from foreign overreach. Together, they signal a unified front against a policy that, if unchecked, could rewrite the rules of digital security, leaving users worldwide—not just in the UK—exposed to the fallout of a single nation’s surveillance ambitions.

(Pictured above: Left, Senator Ron Wyden. Middle, Director of National Intelligence Tulsi Gabbard. Right, Rep. Andy Biggs)

Conclusion

The UK’s clandestine demand in January 2025 for Apple to install a backdoor into its Advanced Data Protection (ADP) encryption has laid bare profound fault lines in the intersecting realms of privacy, security, and global tech governance, igniting a debate that reverberates from Silicon Valley to Westminster. This directive, issued under the Investigatory Powers Act (IPA) and unveiled by The Guardian on February 7, 2025, seeks to dismantle ADP’s end-to-end encryption—secured by 256-bit AES keys and elliptic curve cryptography (ECC) within the Secure Enclave—forcing Apple to grant blanket access to iCloud data worldwide, a scope that transcends the UK’s jurisdiction and exposes over a billion users’ backups, photos, and notes. The fallout has split allies, with the US decrying a violation of sovereignty and Apple disabling ADP for UK users on February 21, 2025, as reported by the Electronic Frontier Foundation, rather than embedding a backdoor like a firmware-injected secondary keypair that would unravel its global security architecture. This clash reveals a fractured landscape where technical realities—encryption’s indivisible strength—collide with political ambitions, straining the Five Eyes alliance and challenging the governance of a digital world reliant on cryptographic trust.

The stakes in this showdown are existential, determining whether encryption remains a bulwark safeguarding users worldwide or becomes a hollow promise that betrays them to surveillance and cyber threats. If Apple acquiesces, integrating a government-accessible key—perhaps a split-key system decrypting ADP’s AES-256 ciphertext—it risks a domino effect, with nations like China and India demanding parity, as Human Rights Watch warned on February 14, 2025, potentially exposing all iCloud data to state-sponsored hackers who’ve already exploited backdoors in breaches like Salt Typhoon. Conversely, Apple’s defiance preserves the Secure Enclave’s hardware-backed entropy and per-device key derivation, ensuring that intercepted data remains indecipherable without user consent—a shield upheld by CISA’s December 2024 guidance advocating end-to-end encryption. The outcome hinges on this binary: either encryption stands firm, protecting activists and ordinary users alike, or it crumbles, leaving a fragmented internet where trust in tech giants like Apple, with its $3.5 trillion market cap, evaporates, and cybersecurity regresses to a pre-encryption era of vulnerability.

This moment demands a clarion call to action, urging readers to grapple with the trade-offs and champion policies that reconcile security with liberty rather than sacrifice one for the other. The UK’s push, justified by the “going dark” problem cited by The Washington Post on February 13, 2025, promises short-term investigative gains but risks long-term peril, as a backdoor’s single point of failure—say, a leaked ECC private key—could be exploited via side-channel attacks or insider threats, per cybersecurity expert Alan Woodward’s warning in The Telegraph on February 13, 2025. Alternatives exist: metadata analysis and device forensics, like Cellebrite’s UFED unlocking seized iPhones, offer law enforcement viable tools without dismantling encryption’s core, yet the IPA’s blunt mandate eschews such nuance. Readers must press policymakers to reject this false dichotomy, advocating for frameworks—like Wyden’s CLOUD Act amendment reported by Nextgov/FCW on February 14, 2025—that bolster both privacy and safety, ensuring tech firms aren’t coerced into weakening systems that protect against escalating cyber threats.

In an era where cyber aggression is surging—evidenced by China’s 2024 telecom incursions—weakening encryption could prove the ultimate own goal, not just for the UK but for the interconnected digital world. The Salt Typhoon breach, detailed by Bank Info Security on February 6, 2025, showed how backdoors amplify state-sponsored hacking; a similar flaw in ADP could hand adversaries a master key to global data troves, undermining critical infrastructure and personal security alike. The UK’s tech reputation, once a beacon, risks crumbling into “pariah” status, as Signal’s Meredith Whittaker argued via Privacy International on February 12, 2025, driving firms like Apple to retreat from markets rather than comply—a loss of innovation and economic clout. This self-inflicted wound threatens to cede the cyber battlefield to those who exploit weakness, leaving allied nations scrambling to reinforce defenses the UK’s policy would erode.

Ultimately, the UK’s backdoor gambit is a high-stakes miscalculation that could haunt the global tech order for decades, a cautionary tale of ambition outpacing foresight. Apple’s refusal and the US’s counteroffensive—blending technical resistance with legislative muscle—signal a refusal to let encryption’s foundation crack, preserving a future where digital trust endures. Yet, the battle is far from won: the IPA’s precedent could still ripple, fragmenting standards like TLS 1.3 or Signal’s double-ratchet, as Wired speculated on February 10, 2025, unless public and expert pressure forces a reckoning. In this crucible, the choice is stark—fortify encryption as a universal shield or watch it unravel, proving that in chasing shadows, the UK might dim the light of security for all.

Sources:

Rusbridger, A. (2025, February 7). UK demands ability to access Apple users’ encrypted data. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2025/feb/07/uk-demands-ability-to-access-apple-users-encrypted-data

Menn, J. (2025, February 7). U.K. orders Apple to let it spy on users’ encrypted accounts. The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/technology/2025/02/07/uk-apple-encryption-order/

Schwartz, M. J. (2025, February 6). Encryption debate: Britain reportedly demands Apple backdoor. Bank Info Security. https://www.bankinfosecurity.com/encryption-debate-britain-reportedly-demands-apple-backdoor-a-26947

Klosowski, T., & Budington, B. (2025, February 21). Cornered by the UK’s demand for an encryption backdoor, Apple turns off its strongest security setting. Electronic Frontier Foundation. https://www.eff.org/deeplinks/2025/02/cornered-uks-demand-encryption-backdoor-apple-turns-its-strongest-security

Callaham, J. (2025, February 7). UK demands Apple break encryption to allow gov’t spying worldwide, reports say. Ars Technica. https://arstechnica.com/tech-policy/2025/02/uk-demands-apple-break-encryption-to-allow-govt-spying-worldwide-reports-say/

Burgess, M. (2025, February 7). UK government demands access to Apple users’ encrypted data. BBC News. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/technology-68234578

Menn, J. (2025, February 13). U.K. demand for a back door to Apple data threatens Americans, lawmakers say. The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/technology/2025/02/13/uk-apple-encryption-congress-response/

Rusbridger, A. (2025, February 26). US national security director condemns UK request for Apple data ‘backdoor’. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2025/feb/26/us-national-security-director-condemns-uk-request-for-apple-data-backdoor

Rusbridger, A. (2025, February 7). UK demands ability to access Apple users’ encrypted data. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2025/feb/07/uk-demands-ability-to-access-apple-users-encrypted-data

Menn, J. (2025, February 7). U.K. orders Apple to let it spy on users’ encrypted accounts. The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/technology/2025/02/07/uk-apple-encryption-order/

Callaham, J. (2025, February 7). UK demands Apple break encryption to allow gov’t spying worldwide, reports say. Ars Technica. https://arstechnica.com/tech-policy/2025/02/uk-demands-apple-break-encryption-to-allow-govt-spying-worldwide-reports-say/

Klosowski, T., & Budington, B. (2025, February 21). Cornered by the UK’s demand for an encryption backdoor, Apple turns off its strongest security setting. Electronic Frontier Foundation. https://www.eff.org/deeplinks/2025/02/cornered-uks-demand-encryption-backdoor-apple-turns-its-strongest-security

Burgess, M. (2025, February 7). UK government demands access to Apple users’ encrypted data. BBC News. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/technology-68234578

Menn, J. (2025, February 13). U.K. demand for a back door to Apple data threatens Americans, lawmakers say. The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/technology/2025/02/13/uk-apple-encryption-congress-response/

Schwartz, M. J. (2025, February 6). Encryption debate: Britain reportedly demands Apple backdoor. Bank Info Security. https://www.bankinfosecurity.com/encryption-debate-britain-reportedly-demands-apple-backdoor-a-26947

Newman, L. H. (2025, February 10). The UK’s encryption fight with Apple could reshape global privacy. Wired. https://www.wired.com/story/uk-encryption-fight-apple-privacy-impact/

Schwartz, M. J. (2025, February 6). Encryption debate: Britain reportedly demands Apple backdoor. Bank Info Security. https://www.bankinfosecurity.com/encryption-debate-britain-reportedly-demands-apple-backdoor-a-26947

Menn, J. (2025, February 7). U.K. orders Apple to let it spy on users’ encrypted accounts. The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/technology/2025/02/07/uk-apple-encryption-order/

Rusbridger, A. (2013, September 6). Revealed: how US and UK spy agencies defeat internet privacy and security. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2013/sep/06/nsa-gchq-encryption-codes-security

Franco, J. (2025, February 14). UK: Encryption order threatens global privacy rights. Amnesty International. https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2025/02/uk-encryption-order-threatens-global-privacy-rights/

Crocker, A. (2024, March 5). European Court of Human Rights confirms: Weakening encryption violates fundamental rights. Electronic Frontier Foundation. https://www.eff.org/deeplinks/2024/03/european-court-human-rights-confirms-weakening-encryption-violates-fundamental

Newman, L. H. (2025, February 10). The UK’s encryption fight with Apple could reshape global privacy. Wired. https://www.wired.com/story/uk-encryption-fight-apple-privacy-impact/

Kennedy, O. (2025, February 14). UK encryption order threatens global privacy rights. Human Rights Watch. https://www.hrw.org/news/2025/02/14/uk-encryption-order-threatens-global-privacy-rights

Rusbridger, A. (2018, September 13). GCHQ data collection regime violated human rights, court rules. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2018/sep/13/gchq-data-collection-violated-human-rights-strasbourg-court-rules

Rusbridger, A. (2025, February 7). UK demands ability to access Apple users’ encrypted data. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2025/feb/07/uk-demands-ability-to-access-apple-users-encrypted-data

Klosowski, T., & Budington, B. (2025, February 21). Cornered by the UK’s demand for an encryption backdoor, Apple turns off its strongest security setting. Electronic Frontier Foundation. https://www.eff.org/deeplinks/2025/02/cornered-uks-demand-encryption-backdoor-apple-turns-its-strongest-security

Newman, L. H. (2025, February 10). The UK’s encryption fight with Apple could reshape global privacy. Wired. https://www.wired.com/story/uk-encryption-fight-apple-privacy-impact/

Schwartz, M. J. (2025, February 6). Encryption debate: Britain reportedly demands Apple backdoor. Bank Info Security. https://www.bankinfosecurity.com/encryption-debate-britain-reportedly-demands-apple-backdoor-a-26947

Menn, J. (2025, February 13). U.K. demand for a back door to Apple data threatens Americans, lawmakers say. The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/technology/2025/02/13/uk-apple-encryption-congress-response/

Callaham, J. (2025, February 7). UK demands Apple break encryption to allow gov’t spying worldwide, reports say. Ars Technica. https://arstechnica.com/tech-policy/2025/02/uk-demands-apple-break-encryption-to-allow-govt-spying-worldwide-reports-say/

Whittaker, M. (2025, February 12). UK’s backdoor demand risks global privacy catastrophe. Privacy International. https://privacyinternational.org/news-analysis/5142/uks-backdoor-demand-risks-global-privacy-catastrophe

CISA. (2024, December 18). CISA guidance on implementing end-to-end encryption. Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency. https://www.cisa.gov/news-events/news/cisa-guidance-implementing-end-end-encryption

Menn, J. (2025, February 7). U.K. orders Apple to let it spy on users’ encrypted accounts. The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/technology/2025/02/07/uk-apple-encryption-order/

Rusbridger, A. (2025, February 7). UK demands ability to access Apple users’ encrypted data. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2025/feb/07/uk-demands-ability-to-access-apple-users-encrypted-data

Klosowski, T., & Budington, B. (2025, February 21). Cornered by the UK’s demand for an encryption backdoor, Apple turns off its strongest security setting. Electronic Frontier Foundation. https://www.eff.org/deeplinks/2025/02/cornered-uks-demand-encryption-backdoor-apple-turns-its-strongest-security

Callaham, J. (2025, February 7). UK demands Apple break encryption to allow gov’t spying worldwide, reports say. Ars Technica. https://arstechnica.com/tech-policy/2025/02/uk-demands-apple-break-encryption-to-allow-govt-spying-worldwide-reports-say/

Whittaker, M. (2025, February 12). UK’s backdoor demand risks global privacy catastrophe. Privacy International. https://privacyinternational.org/news-analysis/5142/uks-backdoor-demand-risks-global-privacy-catastrophe

Schwartz, M. J. (2025, February 6). Encryption debate: Britain reportedly demands Apple backdoor. Bank Info Security. https://www.bankinfosecurity.com/encryption-debate-britain-reportedly-demands-apple-backdoor-a-26947

CISA. (2024, December 18). CISA guidance on implementing end-to-end encryption. Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency. https://www.cisa.gov/news-events/news/cisa-guidance-implementing-end-end-encryption

Newman, L. H. (2025, February 10). The UK’s encryption fight with Apple could reshape global privacy. Wired. https://www.wired.com/story/uk-encryption-fight-apple-privacy-impact/

Menn, J. (2025, February 7). U.K. orders Apple to let it spy on users’ encrypted accounts. The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/technology/2025/02/07/uk-apple-encryption-order/

Wyden, R., & Biggs, A. (2025, February 13). UK accused of political ‘foreign cyber attack’ on US after serving secret snooping order on Apple. Computer Weekly. https://www.computerweekly.com/news/366568198/UK-accused-of-political-foreign-cyber-attack-on-US-after-serving-secret-snooping-order-on-Apple

Kennedy, O. (2025, February 14). UK encryption order threatens global privacy rights. Human Rights Watch. https://www.hrw.org/news/2025/02/14/uk-encryption-order-threatens-global-privacy-rights

Rusbridger, A. (2025, February 26). US national security director condemns UK request for Apple data ‘backdoor’. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2025/feb/26/us-national-security-director-condemns-uk-request-for-apple-data-backdoor

Klosowski, T., & Budington, B. (2025, February 21). Cornered by the UK’s demand for an encryption backdoor, Apple turns off its strongest security setting. Electronic Frontier Foundation. https://www.eff.org/deeplinks/2025/02/cornered-uks-demand-encryption-backdoor-apple-turns-its-strongest-security

Whittaker, M. (2025, February 12). UK’s backdoor demand risks global privacy catastrophe. Privacy International. https://privacyinternational.org/news-analysis/5142/uks-backdoor-demand-risks-global-privacy-catastrophe

Schwartz, M. J. (2025, February 6). Encryption debate: Britain reportedly demands Apple backdoor. Bank Info Security. https://www.bankinfosecurity.com/encryption-debate-britain-reportedly-demands-apple-backdoor-a-26947

Wyden, R. (2025, February 14). Lawmaker looks to strengthen security of U.S. communications following UK’s Apple backdoor order. Nextgov/FCW. https://www.nextgov.com/cybersecurity/2025/02/lawmaker-looks-strengthen-security-us-communications-following-uks-apple-backdoor-order/394374/

Klosowski, T., & Budington, B. (2025, February 21). Cornered by the UK’s demand for an encryption backdoor, Apple turns off its strongest security setting. Electronic Frontier Foundation. https://www.eff.org/deeplinks/2025/02/cornered-uks-demand-encryption-backdoor-apple-turns-its-strongest-security

Menn, J. (2025, February 7). U.K. orders Apple to let it spy on users’ encrypted accounts. The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/technology/2025/02/07/uk-apple-encryption-order/

Wyden, R., & Biggs, A. (2025, February 13). UK accused of political ‘foreign cyber attack’ on US after serving secret snooping order on Apple. Computer Weekly. https://www.computerweekly.com/news/366568198/UK-accused-of-political-foreign-cyber-attack-on-US-after-serving-secret-snooping-order-on-Apple

Rusbridger, A. (2025, February 26). US national security director condemns UK request for Apple data ‘backdoor’. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2025/feb/26/us-national-security-director-condemns-uk-request-for-apple-data-backdoor

Wyden, R. (2025, February 14). Lawmaker looks to strengthen security of U.S. communications following UK’s Apple backdoor order. Nextgov/FCW. https://www.nextgov.com/cybersecurity/2025/02/lawmaker-looks-strengthen-security-us-communications-following-uks-apple-backdoor-order/394374/

Whittaker, M. (2025, February 12). UK’s backdoor demand risks global privacy catastrophe. Privacy International. https://privacyinternational.org/news-analysis/5142/uks-backdoor-demand-risks-global-privacy-catastrophe

Warren, T. (2025, February 13). UK’s Apple encryption demands spark global security fears, experts warn. The Telegraph. https://www.telegraph.co.uk/technology/2025/02/13/uks-apple-encryption-demands-spark-global-security-fears/

Newman, L. H. (2025, February 10). The UK’s encryption fight with Apple could reshape global privacy. Wired. https://www.wired.com/story/uk-encryption-fight-apple-privacy-impact/

Rusbridger, A. (2025, February 7). UK demands ability to access Apple users’ encrypted data. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2025/feb/07/uk-demands-ability-to-access-apple-users-encrypted-data

Klosowski, T., & Budington, B. (2025, February 21). Cornered by the UK’s demand for an encryption backdoor, Apple turns off its strongest security setting. Electronic Frontier Foundation. https://www.eff.org/deeplinks/2025/02/cornered-uks-demand-encryption-backdoor-apple-turns-its-strongest-security

Kennedy, O. (2025, February 14). UK encryption order threatens global privacy rights. Human Rights Watch. https://www.hrw.org/news/2025/02/14/uk-encryption-order-threatens-global-privacy-rights

Menn, J. (2025, February 13). U.K. demand for a back door to Apple data threatens Americans, lawmakers say. The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/technology/2025/02/13/uk-apple-encryption-congress-response/

Warren, T. (2025, February 13). UK’s Apple encryption demands spark global security fears, experts warn. The Telegraph. https://www.telegraph.co.uk/technology/2025/02/13/uks-apple-encryption-demands-spark-global-security-fears/

Wyden, R. (2025, February 14). Lawmaker looks to strengthen security of U.S. communications following UK’s Apple backdoor order. Nextgov/FCW. https://www.nextgov.com/cybersecurity/2025/02/lawmaker-looks-strengthen-security-us-communications-following-uks-apple-backdoor-order/394374/

Schwartz, M. J. (2025, February 6). Encryption debate: Britain reportedly demands Apple backdoor. Bank Info Security. https://www.bankinfosecurity.com/encryption-debate-britain-reportedly-demands-apple-backdoor-a-26947

Newman, L. H. (2025, February 10). The UK’s encryption fight with Apple could reshape global privacy. Wired. https://www.wired.com/story/uk-encryption-fight-apple-privacy-impact/