China’s $225 billion to $600 billion per year theft: Chinese Industrial Espionage

The 7 Most Egregious Cases of Chinese Industrial Espionage Against the US

TL;DR:

China’s Industrial Espionage Against the U.S.: Chinese industrial espionage has cost the U.S. economy between $225 billion and $600 billion annually, targeting critical industries such as aerospace, telecommunications, and renewable energy. Driven by strategic objectives like "Made in China 2025," China uses cyber intrusions, insider threats, and regulatory pressure to acquire U.S. technology and intellectual property, undermining innovation and national security.

Historical and Strategic Context: Since the Cold War, China has pursued espionage to close technology gaps. Early efforts, such as leveraging defectors like Qian Xuesen, evolved into cyber campaigns like Operation Aurora (2010). The espionage aligns with China’s goals to dominate high-tech sectors and modernize its military while reducing dependency on foreign technologies.

Notable Espionage Cases:

Operation Aurora (2009): Targeted Google and major U.S. firms, stealing intellectual property and surveilling dissidents.

Dongfan "Greg" Chung (2008): A Boeing engineer passed aerospace and military secrets to China over decades.

SolarWorld Hack (2014): Chinese hackers stole trade litigation and manufacturing data, undermining U.S. solar energy competitiveness.

GE Aviation (2018): MSS agents attempted to steal aviation turbine technology to boost China’s aerospace capabilities.

Sinovel Wind Group (2011): Stole wind turbine technology from AMSC, resulting in financial losses and layoffs.

Methods and Techniques: China employs advanced persistent threats (APTs), human intelligence (HUMINT), and regulatory strategies to access proprietary data. Cyber tactics include spear-phishing, malware deployment, and zero-day exploits, while insider recruitment and forced technology transfers leverage economic and academic relationships.

Impact on the U.S.: Economic losses from Chinese espionage erode U.S. competitiveness, stifling innovation and leading to job cuts in key industries. National security risks include compromised military technology and critical infrastructure vulnerabilities. The theft of intellectual property affects sectors critical to U.S. leadership, such as renewable energy and aerospace.

Policy Responses: The U.S. has enacted measures like the CHIPS Act to boost domestic tech production and FIRRMA to scrutinize foreign investments. Cybersecurity policies have been strengthened, while the Justice Department’s China Initiative targeted espionage cases, though it faced criticism for potential profiling. Export controls and sanctions aim to curb China’s access to sensitive technologies.

International Reactions: Allies like the EU, Australia, and Canada have also tightened cybersecurity and investment laws, often coordinating through alliances like Five Eyes. Diplomatic tensions between the U.S. and China over espionage have fueled global calls for cybersecurity norms and reduced reliance on Chinese technology.

Future Outlook: Addressing industrial espionage requires stronger cybersecurity, robust legal frameworks, and international collaboration. The U.S. must invest in innovation and safeguard critical sectors while balancing diplomatic efforts with China. Leveraging allied partnerships and enforcing global standards will be vital in countering emerging threats.

And now the Deep Dive….

Introduction

Industrial espionage, often referred to as economic or corporate espionage, involves the theft of business secrets or proprietary information for competitive advantage. This clandestine activity can significantly influence international relations and economic dynamics between countries, as it not only affects the immediate companies involved but also the broader technological and economic landscapes. Within this context, the scale and sophistication of Chinese industrial espionage against the United States have been particularly notable, raising alarms about national security, economic stability, and the integrity of intellectual property rights. This essay will delve into some of the most egregious cases of Chinese industrial espionage against the U.S., focusing on how these incidents have underscored the strategic rivalry between the two nations and the profound implications for U.S. industries and innovation.

Historical Context

Following the establishment of the People's Republic of China in 1949, the newly formed government under Mao Zedong embarked on a path that would see extensive espionage activities against the United States, particularly during the Cold War era. One of the earliest notable instances involved Qian Xuesen, a former Caltech professor and co-founder of the Jet Propulsion Laboratory. In 1950, accused of having connections to the Communist Party, Qian was stripped of his security clearance, leading to his eventual return to China in 1955 after a period under house arrest. His expertise in rocketry significantly bolstered China's missile and space programs, marking the beginning of a long-term strategy to harness Western technology for national development. Another significant early case was that of Larry Wu-Tai Chin, a CIA translator who spied for China from 1944 until his arrest in 1985. His espionage activities included leaking sensitive U.S. intelligence documents, providing the Chinese with insights into U.S. foreign policy and military strategies during critical Cold War moments.

As the world transitioned into the digital age, the methods of Chinese espionage against the U.S. evolved dramatically. While traditional espionage through human intelligence remained, there was a marked shift towards cyber espionage with the proliferation of the internet and advanced computing technology. The late 20th and early 21st centuries saw China leveraging cyber capabilities for what has been termed as "Operation Aurora" in 2010, where numerous U.S. companies, including Google, were targeted for intellectual property theft. This operation highlighted the sophistication of Chinese cyber tactics, utilizing malware and spear-phishing to infiltrate systems. By the 2010s, cyber espionage campaigns like those attributed to the Chinese military unit 61398 had become notorious for hacking into U.S. corporations to steal trade secrets, business plans, and sensitive data. These cyber operations often aimed at sectors where China sought to catch up or overtake Western technology, including aerospace, technology, and pharmaceuticals.

The strategic motivations behind China's espionage activities are multifaceted but centered around several key objectives. Primarily, China has sought to advance its technological and industrial capabilities to leapfrog development stages, thereby enhancing its global competitive standing without the extensive research and development costs incurred by Western nations. This approach is part of a broader national strategy to achieve "Made in China 2025," an initiative aimed at elevating China to a global leader in high-tech industries. Another significant motivation involves military modernization. By acquiring U.S. military technology, China aims to close the technological gap, thereby strengthening its defense capabilities and projecting power in regional and global arenas. Espionage also serves as a tool for geopolitical strategy, where insights into U.S. policy, economic trends, and technological advancements can influence China's diplomatic, economic, and military decisions. Moreover, with the fusion of civilian and military technologies, espionage becomes a means to dual-use technology acquisition, where civilian innovations can be repurposed for military applications, enhancing China's strategic depth in both peace and conflict scenarios.

These motivations have not only been about immediate gains but also about long-term strategic positioning. By absorbing and adapting foreign technology, China reduces its dependency on external sources, builds a self-sufficient innovation ecosystem, and challenges the U.S.'s technological hegemony. The implications of these espionage efforts are profound, affecting not just bilateral relations but also global economic and security architectures, as nations grapple with how to protect their intellectual property while engaging in an increasingly interconnected world.

(Pictured above: Qian Xuesen)

Unit 61398

The genesis of Chinese military unit 61398 dates back to the early 21st century, with its operations becoming noticeable to Western intelligence by around 2006. The exact inception date is somewhat obscured due to the secretive nature of such military units, but it aligns with China's broader push into cyber capabilities during this period, as part of technological and military modernization strategies. This was a time when the People's Liberation Army (PLA) was significantly investing in information warfare and cyber operations, recognizing the strategic importance of cyberspace in modern conflicts and economic competition.

Unit 61398 began as part of the PLA's General Staff Department's Third Department, specifically under the Second Bureau, which is responsible for signals intelligence and cyber operations. The establishment of this unit can be seen as a response to the increasing reliance on digital infrastructure in both civilian and military sectors globally. China, recognizing the vulnerabilities and opportunities in cyberspace, expanded its capabilities by recruiting from top-tier universities like Zhejiang University, where it sought graduates with high expertise in computer science, often with scholarships tied to service commitments in the unit. This recruitment strategy not only ensured a supply of skilled personnel but also embedded the unit within a broader academic and research ecosystem, facilitating the rapid development of cyber capabilities.

Unit 61398, also known by various aliases such as APT1, Comment Crew, or Shanghai Group, is officially a Military Unit Cover Designator (MUCD) within the PLA. It is an advanced persistent threat (APT) group, meaning it conducts long-term, targeted cyber espionage against specific entities. This unit is not merely a collection of hackers but an organized military unit with structured operations, state backing, and clear strategic objectives, primarily focused on espionage and intellectual property theft to advance China's technological and military capabilities.

Geographically, Unit 61398 is based in a nondescript 12-story building in Pudong, Shanghai. This location, off Datong Road, has been pinpointed by various cybersecurity firms and U.S. intelligence as the epicenter of many cyber attacks attributed to this group. The building's unassuming facade belies its significant role in China’s cyber warfare strategy, with satellite dishes on the roof suggesting an extensive infrastructure for communication and data interception.

The capabilities of Unit 61398 are extensive and sophisticated. They include the ability to conduct massive, coordinated attacks against multiple targets simultaneously, stealing hundreds of terabytes of data. The unit is known for using custom malware, spear-phishing emails, and zero-day exploits, showcasing a high level of technical proficiency and resourcefulness. Their operations are not just about immediate data theft but also about establishing persistent access to networks, allowing for long-term espionage where they can extract valuable information over extended periods. This capability has made them one of the most prolific cyber espionage units tracked by Western security firms.

In terms of tactics, Unit 61398 employs a variety of methods tailored to their targets. Spear-phishing is a common tactic, where attackers send emails that appear to come from trusted sources within an organization, tricking recipients into revealing sensitive information or clicking on malicious links. They also use watering hole attacks, where they compromise websites likely to be visited by their targets, thereby infecting systems when employees visit these sites. Another tactic involves exploiting vulnerabilities in software or systems before they are widely known (zero-day exploits), giving them a window to operate before patches are developed. The unit's operations also include the use of backdoors placed in systems for future access, ensuring ongoing surveillance or data theft capabilities.

Unit 61398 has been linked to numerous high-profile cyber incidents, notably targeting U.S. corporations in sectors like aerospace, satellite, telecommunications, and information technology. Their activities have included stealing blueprints, proprietary manufacturing processes, and strategic business plans, which not only harm individual companies but also affect national security by potentially transferring critical technology to China. The scale of their operations was highlighted by U.S. cybersecurity firm Mandiant in their 2013 report, which detailed how the unit systematically targeted and exfiltrated data from at least 141 organizations across 20 industries.

However, the landscape of cyber espionage is continuously evolving, and while Unit 61398 has been a focal point of discussions on Chinese cyber activities, it is but one part of a larger, more complex network of state-sponsored cyber operations. The activities of this unit have led to significant diplomatic and legal repercussions, including U.S. indictments of PLA officers in 2014, reflecting the growing tension over cyber espionage in U.S.-China relations. Despite these measures, the covert nature of their operations and the strategic importance of the intelligence gathered ensure that such activities continue to be a point of contention and a significant aspect of modern geopolitical strategy.

(Pictured above: The building where Unit 61398 is)

Other Non-military Actors in China

The question of whether China employs actors beyond its military unit 61398 to conduct industrial espionage is not only pertinent but has been substantiated by multiple investigations and reports from various cybersecurity firms and government agencies. While Unit 61398, also known as APT1, has been one of the most publicized groups due to its direct link to the People's Liberation Army (PLA), it is clear that China's espionage apparatus extends far beyond this single unit, involving a sophisticated network of state-sponsored and state-affiliated actors.

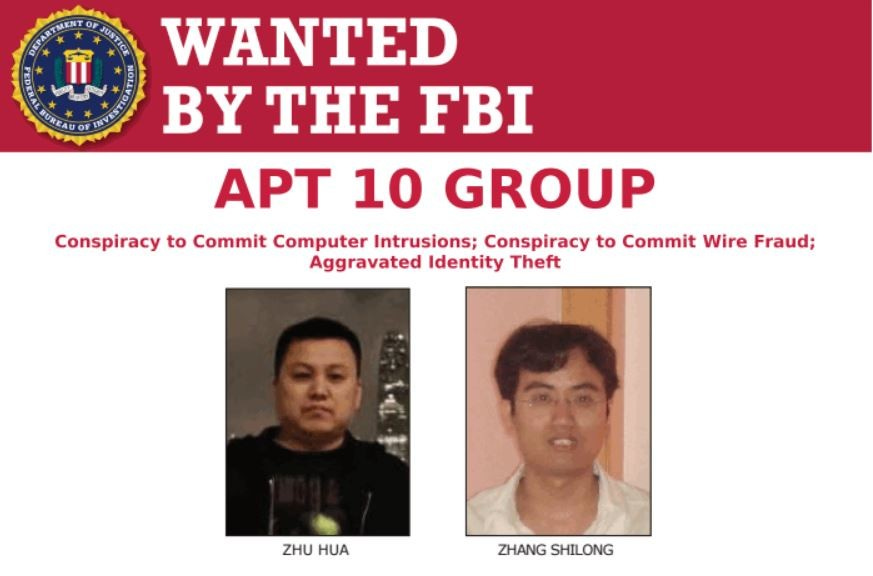

One such group is APT10, also known as Stone Panda or Red Apollo. This group has been linked to the Ministry of State Security (MSS), China's civilian intelligence agency, rather than the military. APT10 has been accused of targeting managed IT service providers to gain access to the networks of their clients, primarily in sectors like healthcare, biotechnology, and manufacturing. Their operations have involved the theft of sensitive business information, intellectual property, and personal data, aligning with China's economic espionage objectives rather than purely military ones.

Another significant player in China's industrial espionage landscape is APT41, which operates somewhat uniquely as it is believed to be a dual-purpose entity, engaging in both state-sponsored cyber operations and criminal activities for profit. APT41 has been observed targeting industries like video gaming, healthcare, and high-tech manufacturing for intellectual property theft. This group's activities highlight the blurred lines between state-sponsored espionage and cybercrime, where the skills and infrastructure developed for state needs can be repurposed for personal gain, yet ultimately serve China's broader economic interests.

The Winnti Group, often associated with operations under the umbrella term "Barium", has also been implicated in extensive industrial espionage campaigns. Known for targeting the video game industry, pharmaceutical companies, and automotive sectors, Winnti's methods involve the use of custom malware to steal source code, R&D data, and other proprietary information. While not directly linked to a specific government entity, their activities are believed to contribute to China's national strategy of technological leapfrogging, where foreign innovations are quickly absorbed into the domestic market.

Beyond these named groups, there are numerous other less publicized or newly identified actors, such as APT3 or Gothic Panda, which have been linked to cyber espionage activities targeting sectors critical to China's industrial growth, like finance, energy, and chemicals. These groups often use similar tactics to Unit 61398 but operate with different affiliations within China's sprawling security apparatus, including regional security services or universities that are part of the military-civil fusion strategy.

The structure of this espionage network often involves a mix of direct state employees, contractors, and even unwitting or coerced insiders within targeted companies. For instance, the MSS has been known to recruit individuals from the academic and business sectors in foreign countries, offering them incentives to provide China with proprietary technology or strategic business insights. This approach leverages human intelligence alongside cyber methods, showing a comprehensive strategy to industrial espionage.

Moreover, the involvement of private companies in China, under government directives, is another layer of this espionage activity. Firms like Huawei and ZTE have faced allegations of espionage, where their technology could potentially be used to facilitate spying. While these allegations are often met with denials, the close relationship between these companies and the Chinese state, including laws compelling assistance to state intelligence, suggests a complex web where corporate and espionage interests intersect.

The use of these varied actors outside of Unit 61398 underscores a strategic approach by China to gather industrial intelligence, where the focus is not just on military advantage but on gaining economic leverage through the acquisition of advanced technologies, trade secrets, and market strategies. This multi-faceted espionage network reflects China's view of economic and technological development as a key component of national power, necessitating a broad, coordinated effort that leverages all available resources, both within and beyond the traditional military structures.

Key Cases of Espionage

Case 1: Operation Aurora (2009)

Operation Aurora, revealed in 2010, stands as one of the most notorious cases of industrial espionage orchestrated from China, with significant implications for U.S. companies and international relations. This cyberattack campaign initially came to public attention when Google disclosed that it had been targeted by a sophisticated hacking operation since mid-2009. The attacks were not just an attempt to steal intellectual property but also aimed at accessing the Gmail accounts of Chinese human rights activists, indicating a blend of economic espionage with political motivations.

Google's investigation into these intrusions revealed that the attackers had exploited a zero-day vulnerability in Internet Explorer, managed to penetrate the company's internal systems, and accessed source code repositories. This was not an isolated incident. Google estimated that at least 20 other major companies, including Adobe, Yahoo, Symantec, and Juniper Networks, were similarly targeted. The attack involved a malware dubbed Hydraq, which allowed the perpetrators to establish backdoors into corporate networks, thus facilitating the theft of extensive amounts of intellectual property.

The revelation by Google was groundbreaking not only because of the scale and sophistication of the attack but also due to the company's decision to publicly attribute the cyberattacks to actors in China. This move was rare, as many corporations were reluctant to name China for fear of damaging business relations or facing retaliatory actions. Google's public stance highlighted the severity of the situation, leading to an immediate response from other affected companies, some of whom had been unaware of the breaches until Google's disclosure.

The impact on U.S. companies was profound. The theft of source code could potentially allow competitors to develop similar or reverse-engineered products, undermining years of innovation and investment. For Google, the incident was a catalyst to re-evaluate its operations in China. In response, Google announced it would no longer censor its search results in China, which eventually led to the company redirecting its Chinese search services to Hong Kong in March 2010. This shift showcased the tension between operating in a lucrative market versus maintaining ethical and security standards.

On the international stage, Operation Aurora significantly strained U.S.-China relations. It fueled debates about cyber sovereignty, espionage, and the ethics of state-sponsored cyber activities. The U.S. government, already wary of China's cyber capabilities, intensified its rhetoric against such acts, with then-Secretary of State Hillary Clinton delivering a speech that underscored the U.S. commitment to Internet freedom and implicitly criticized China's control over cyberspace. This incident was one of several that contributed to the U.S. adopting a more confrontational stance on cybersecurity, leading to legislative proposals and policy shifts aimed at enhancing national cyber defenses.

The case also prompted a broader discussion about the need for international cyber norms and treaties. It was a wake-up call for corporations worldwide to bolster their cybersecurity measures, as even giants like Google were vulnerable. This led to increased investments in cybersecurity, both in terms of technology and human resources, and a push towards more robust public-private partnerships to share intelligence about threats.

Furthermore, Operation Aurora brought attention to the dual-use nature of cyber capabilities where espionage could serve both economic and political ends. It highlighted the challenges of distinguishing between state-sponsored actions aimed at national strategic interests versus those intended to benefit the private sector, blurring the lines in international law and diplomacy. The incident catalyzed a global conversation about the ethics of digital espionage, data protection, and the sovereignty of data, especially when human rights were implicated.

In the long term, Operation Aurora has been remembered as a turning point in the narrative of cyber warfare and espionage. It underscored the necessity for companies to consider not only the financial implications of cyberattacks but also their geopolitical ramifications. The event continues to influence how nations and corporations address the complexities of cybersecurity in an age where digital information is both an asset and a battleground, shaping policies, corporate strategies, and international relations well into the future.

Case 2: Dongfan "Greg" Chung (2008)

Dongfan "Greg" Chung was at the center of one of the most significant cases of economic espionage in the United States, highlighting the vulnerabilities of even the most secure industries to insider threats. Born in China, Chung immigrated to the U.S., where he became a naturalized citizen and worked for decades in the aerospace industry. He began his career at Rockwell International in 1973, where he was involved with the Space Shuttle program, and continued when the company was acquired by Boeing in 1996. His role as a stress analyst gave him access to highly sensitive information regarding various aerospace technologies, including those critical to national security.

Chung's espionage activities came to light in 2006 when the FBI, investigating another espionage case involving Chi Mak, stumbled upon evidence linking Chung to similar activities. The investigation revealed that for over 30 years, Chung had been siphoning off proprietary and classified information related to the U.S. Space Shuttle, Delta IV rocket, and other military projects, intending to pass this to China. The FBI's search of Chung's home uncovered a staggering 250,000 pages of documents, some hidden beneath his house, which were Boeing's trade secrets, including detailed technical data and design specifics.

In February 2008, Chung was indicted on charges of economic espionage, conspiracy to commit economic espionage, acting as an unregistered foreign agent, and making false statements. These charges were part of the first trial under the Economic Espionage Act of 1996, marking a pivotal moment in U.S. legal history concerning industrial espionage. The trial, which was a bench trial presided over by U.S. District Judge Cormac J. Carney, concluded with Chung being convicted in July 2009 on multiple counts, including six counts of economic espionage and one count of acting as an agent of the People's Republic of China.

The legal outcomes were severe. Chung was sentenced to 15 years and 9 months in federal prison in February 2010, one of the longest sentences for such a crime at that time. This sentence was intended to send a strong message about the seriousness with which the U.S. views economic espionage, particularly when it involves military and space technology. The conviction also included financial penalties, although the exact amount of damage to Boeing and U.S. national security was difficult to quantify due to the breadth of information compromised over such an extended period.

The broader implications of Chung's case were multifaceted. Firstly, it exposed the extent to which insiders could exploit their positions to conduct espionage over decades without detection, leading to a reevaluation of security protocols within companies dealing with sensitive technologies. It underscored the need for continuous monitoring, stringent access controls, and the importance of security clearance checks, even for long-term, trusted employees.

Secondly, the case had significant repercussions for U.S.-China relations. It fueled debates about intellectual property theft, national security, and the ethical dimensions of international trade and cooperation. The Chung case was often cited in discussions about the need for tighter regulations on technology transfers and the protection of proprietary information, especially in industries critical to national defense.

From a policy perspective, the case contributed to a hardening of U.S. attitudes towards espionage from China, leading to legislative efforts like the Foreign Investment and National Security Act of 2007, which aimed to scrutinize foreign investments in sensitive sectors more closely. It also spurred greater inter-agency cooperation in counterintelligence, with agencies like the FBI, NASA, and Defense Department enhancing their collaboration to prevent similar breaches in the future.

Moreover, Chung's case became a reference point for discussing the balance between openness in scientific and industrial collaboration and the need for safeguarding national interests. It served as a cautionary tale for companies engaging in global business, particularly in fields where technology transfer could have dual-use implications. This incident led to a more vigilant corporate culture around cybersecurity, espionage awareness training, and the safeguarding of intellectual capital, influencing how companies and governments worldwide approach the protection of sensitive information.

(Pictured above: Dongfan "Greg" Chung)

Case 3: SolarWorld vs. Chinese Hackers (2014)

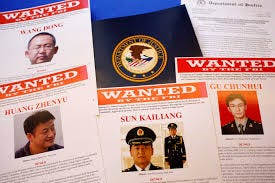

In May 2014, a significant case of industrial espionage came to light when the U.S. Department of Justice announced charges against five Chinese military officers for hacking into SolarWorld, among other U.S. companies. SolarWorld, a U.S. subsidiary of the German solar panel manufacturer SolarWorld AG, had become a prime target due to its leading position in the U.S. solar market and its aggressive stance against Chinese solar manufacturers in trade disputes. The hackers, identified as members of the Chinese People's Liberation Army (PLA) Unit 61398, were part of a broader campaign to steal sensitive commercial information that could give Chinese companies an edge in international competition.

The infiltration of SolarWorld began around May 2012, coinciding with the company's involvement in high-profile trade cases against Chinese solar manufacturers, accusing them of dumping solar products in the U.S. market at below-market prices. The hackers used sophisticated techniques, including spear-phishing emails to deceive employees into revealing credentials or clicking malicious links. Once inside SolarWorld's network, they stole thousands of emails, documents, and proprietary information, including cash flow records, manufacturing metrics, cost structures, and strategic discussions regarding ongoing trade litigations. This information was crucial for understanding SolarWorld's competitive vulnerabilities and could be used to undermine its position in the market.

The stolen data directly impacted SolarWorld's ability to compete. It included highly confidential details about production capabilities and pricing strategies, which, if exploited by competitors, could help them undercut SolarWorld's prices or rapidly mimic its technological advancements. The hackers' activities were not just about stealing proprietary technology but also about gaining insights into SolarWorld's legal strategies in trade disputes, which could allow Chinese companies to anticipate and counteract U.S. efforts to impose tariffs or other trade barriers.

The consequences for the solar industry were immediate and profound. SolarWorld, already struggling with competition from heavily subsidized Chinese manufacturers, found itself at a further disadvantage. The company had been a vocal advocate for trade protections, leading to anti-dumping duties in 2012 that aimed to level the playing field. However, with the espionage, Chinese competitors potentially had access to SolarWorld's playbook, making it harder for the company to maintain its market share and profitability. This case underscored the challenges U.S. companies faced in protecting intellectual property in sectors where China sought to dominate.

The broader implications for the U.S. economy were significant. The solar industry, seen as a burgeoning sector for green jobs and innovation, was directly threatened by such espionage. SolarWorld's case was part of a larger narrative where U.S. companies in various industries were losing competitive ground due to intellectual property theft. This not only affected individual firms but also had ripple effects on employment, innovation, and the overall competitiveness of the U.S. in clean energy technologies. The incident fueled calls for stronger cybersecurity measures, legislative action against economic espionage, and a reevaluation of trade policies with China.

Legally, the case set a precedent as it was the first time the U.S. had indicted state actors for cyber espionage explicitly. Although the likelihood of extraditing the accused from China was low, the indictments served as a diplomatic tool, signaling U.S. resolve to combat state-sponsored cyber theft. This event also influenced international discussions on cyber norms, with the U.S. pushing for agreements that would criminalize such espionage globally.

In response, SolarWorld sought further U.S. government intervention, including an investigation by the Commerce Department into whether Chinese cyber espionage constituted a basis for new or additional trade remedies. This move aimed to close loopholes in existing tariffs where Chinese companies had begun routing solar cell production through Taiwan to circumvent duties. The case highlighted how cyber espionage could become intertwined with trade policy, affecting how tariffs and trade agreements are negotiated and enforced.

Ultimately, the SolarWorld vs. Chinese Hackers case was a stark reminder of the ongoing cyber threats to U.S. industries, particularly those in sectors where China aims to lead globally. It led to increased awareness of cybersecurity among businesses, more stringent security protocols, and a push towards more robust international cooperation to tackle cyber espionage, reflecting the complex interplay between technology, trade, and national security in the modern era.

Case 4: GE Aviation

The espionage case involving GE Aviation exemplifies how Chinese entities have employed sophisticated tactics to acquire sensitive U.S. technology, often through the recruitment of insiders or leveraging academic and business collaborations. At the heart of this saga is Yanjun Xu, a senior officer with China's Ministry of State Security (MSS), who was instrumental in orchestrating espionage operations aimed at stealing trade secrets from American companies, including GE Aviation.

Yanjun Xu's involvement in espionage was revealed through a complex operation where he used his position to target GE Aviation, among other U.S. firms. Xu's primary tactic was the recruitment of insiders, specifically engineers and experts within these companies who had access to proprietary technology. He would invite these individuals to China under the guise of academic or professional collaborations, often with the cover of giving presentations at universities or conferences. These invitations were not merely for knowledge exchange. They were a pretext for espionage. Xu would pay for travel, accommodation, and even offer stipends, making the proposition attractive to those targeted.

One specific instance involved Xu attempting to recruit an engineer from GE Aviation, who specialized in turbine technology. This engineer was lured to China to give a presentation at a university in Nanjing in May 2017. Unbeknownst to Xu, by the time this meeting occurred, the engineer had already begun cooperating with the FBI, who had been alerted to potential espionage activities. The engineer was instructed to continue communications with Xu, leading to an orchestrated meeting in Belgium in April 2018, where Xu was arrested. This operation highlighted the use of human intelligence in Chinese espionage, where personal relationships and trust were exploited to transfer sensitive technology.

The methods employed by Xu included not just the recruitment of insiders but also the use of digital means to steal information. He would ask for detailed technical documents during these engagements, which he believed would help advance China's aviation technology, particularly in areas like composite aircraft engine fans where GE Aviation was a global leader. His tactics extended to using cyber techniques when possible, although human intelligence was his primary approach.

The legal consequences for Xu were significant. Extradited from Belgium to the U.S. in 2018, he was convicted in November 2021 of economic espionage and attempting to steal trade secrets. His sentencing in November 2022 to 20 years in prison underscored the U.S. judicial system's approach to dealing with state-sponsored espionage. This case was pivotal as it was the first time a Chinese intelligence officer was extradited to the U.S. for trial on such charges, setting a legal precedent.

The implications of these espionage tactics extend beyond the immediate legal outcomes. For GE Aviation, the exposure of such activities led to a reevaluation of security practices, particularly in how it manages intellectual property and collaborates internationally. The incident highlighted vulnerabilities in the protection of sensitive information, even within large, security-conscious corporations. It also intensified scrutiny over Chinese involvement in U.S. technology sectors, leading to increased caution in academic and business collaborations with Chinese entities.

On a broader scale, this case contributed to the deteriorating U.S.-China relations, particularly in the realm of technology and trade. It was cited in discussions about the need for stricter export controls, more robust cybersecurity measures, and a rethinking of how U.S. companies engage with Chinese counterparts. The espionage tactics used in this case – mixing human intelligence with cyber operations and leveraging international business and academic exchanges – have become focal points for national security discussions, urging better safeguards for intellectual property and technological innovation in an increasingly interconnected world.

(Pictured above: Yanjun Xu)

Case 5: Super Micro Computer Inc. Incident

The Super Micro Computer Inc. Incident, which became public knowledge through a 2018 Bloomberg Businessweek report, represents one of the most alarming cases of potential hardware-level espionage affecting national security and the integrity of the tech supply chain. Super Micro, known as Supermicro, is a major supplier of server components and systems to numerous U.S. companies, including tech giants like Amazon and Apple, and various government agencies. The incident allegedly involved the insertion of tiny, malicious microchips into hardware manufactured for these clients, specifically aimed at providing unauthorized access to sensitive data.

The overview of this case centers on the claim that these compromised microchips were inserted during the manufacturing process in China. According to Bloomberg's report, these chips were minuscule, likened to the size of a grain of rice, and were placed on the motherboards of Supermicro servers. This hardware manipulation allegedly allowed the chips to create a stealth backdoor, enabling data exfiltration to servers controlled by Chinese intelligence. The sophistication of this attack suggested a long-term, systemic infiltration of the supply chain, posing a grave risk to data security across numerous sectors.

The implications for national security were profound. If true, this incident suggested that sensitive data from U.S. government agencies, including those involved in defense, intelligence, and cybersecurity, could have been compromised. The potential for such hardware to be embedded in systems handling classified information raised questions about the vulnerability of the U.S. to espionage at a hardware level, where traditional cybersecurity measures might not detect such physical alterations. This case highlighted the complexities of securing hardware supply chains in an era where global manufacturing is the norm, especially when critical components are produced in countries with strategic interests counter to those of the U.S.

For the tech industry, the revelations had immediate and long-term effects on the supply chain. Companies like Amazon and Apple, although vehemently denying the specifics of the Bloomberg report, began to reassess their supply chain strategies to mitigate risks of hardware tampering. This led to an increase in due diligence, more rigorous quality control processes, and a push towards greater transparency in manufacturing practices. Some organizations also started to bring parts of their manufacturing back to the U.S. or to more trusted allies, aiming to reduce reliance on potentially vulnerable supply chains.

The incident also sparked a broader dialogue about the security of hardware in a world where technology is increasingly interconnected and where physical security of devices is as critical as software security. There was a push for new standards and certifications for hardware integrity, similar to what exists for software, to ensure that what is being purchased is free from unauthorized modifications. This case underscored the need for hardware security assessments to become as routine as software vulnerability scans.

Legally and diplomatically, the Supermicro incident strained U.S.-China relations further, with mutual accusations of espionage and calls for more stringent controls on technology exports. The U.S. government began to tighten policies around technology transfer and foreign investment in sensitive tech sectors. This event was cited in discussions leading to the passage of laws like the CHIPS Act, aimed at strengthening domestic semiconductor production capabilities, thereby reducing dependency on foreign manufacturers for critical tech components.

Despite the significant impact on policy and corporate behavior, the actual details and proof of the Supermicro incident remain contentious. Supermicro, along with companies like Apple and Amazon, issued strong denials, and independent investigations commissioned by Supermicro found no evidence of the claimed malicious chips. However, the absence of conclusive evidence did not diminish the incident's role in catalyzing changes in how the tech industry approaches supply chain security.

In the aftermath, there was a notable shift in how companies and governments viewed supply chain risks. The incident was a wake-up call that even hardware could be a vector for espionage, leading to advancements in supply chain security practices, such as enhanced inspection protocols, the use of blockchain for tracking components, and more stringent supplier vetting. It also highlighted the ongoing geopolitical tensions where technology supply chains are not just about economics but are central to national security considerations, influencing how nations strategize their technological sovereignty and defense against espionage.

Case 6: American telecom firms

The espionage involving American telecom firms has been a significant and evolving concern, particularly highlighted by recent events that underscore the vulnerability of telecommunications infrastructure to cyber threats from state actors like China. The case of American telecom firms being compromised by Chinese hackers involves multiple layers, from direct cyber intrusions to the strategic implications of such breaches for both national security and the integrity of communication networks.

The narrative around these incidents was dramatically amplified in late 2024, when the White House disclosed details of a massive Chinese hacking campaign that had infiltrated at least eight U.S. telecom companies. This campaign, described as one of the largest hacks on American telecommunications firms, allowed Chinese officials access to private texts and phone conversations. The implications were severe, as this access could potentially compromise sensitive communications involving not only everyday citizens but also government officials and high-profile political figures, thereby posing a direct threat to national security.

The tactics used in these espionage activities were sophisticated and multifaceted. Hackers primarily exploited weaknesses in the network infrastructure, often gaining entry through compromised credentials or vulnerabilities in third-party software. Once inside, they could establish long-term access points, essentially creating backdoors through which they could monitor, intercept, or manipulate communications. This level of intrusion suggests a capability for not just espionage but also for potential disruption of services if needed for strategic purposes.

The impact on the affected telecom firms was immediate. Companies had to scramble to secure their networks, which often meant significant operational disruptions as they implemented emergency security measures or patches. The reputational damage was considerable, as trust in these firms to protect customer data was eroded. Moreover, the financial implications included not just the cost of remediation but also potential legal liabilities for failing to safeguard communications, especially if sensitive data was exposed.

From a national security standpoint, the breach into telecom infrastructure raised alarms about the sanctity of communication lines used by government agencies, military, and law enforcement. The potential for such networks to be tapped for intelligence could undermine operations, diplomatic efforts, and even personal security of individuals involved in sensitive roles. This incident highlighted the need for enhanced cybersecurity measures specifically tailored to protect telecom infrastructure, which is often seen as critical national infrastructure.

The broader implications for the tech supply chain and international relations were also significant. This incident fed into ongoing debates about the security of equipment from countries like China, particularly after previous controversies involving companies like Huawei and ZTE. It led to a reevaluation of how much reliance should be placed on technology from nations with whom there are strategic tensions. The U.S. government's response included calls for more stringent cybersecurity standards for telecom providers and revisiting the policies regarding foreign technology in U.S. networks.

Diplomatically, these breaches further complicated U.S.-China relations, adding to the narrative of cyber espionage and the need for cyber norms internationally. China, while often denying direct involvement in such activities, faced increased pressure and scrutiny, with some U.S. policy makers advocating for stronger sanctions or restrictions on Chinese tech companies. This case also prompted discussions at international forums about the rules of engagement in cyberspace and the protection of critical infrastructure from foreign interference.

In response to these breaches, there was a push towards greater collaboration between private telecom firms and government agencies to bolster defenses. This included sharing threat intelligence, conducting regular security audits, and developing new technologies for detecting and preventing such intrusions. The incident served as a stark reminder of the evolving nature of cybersecurity threats, where traditional boundaries between military, government, and civilian sectors blur, requiring an integrated approach to security that encompasses all aspects of digital infrastructure.

Ultimately, the case of espionage involving American telecom firms underscored the critical importance of cybersecurity in telecommunications. It highlighted not only the technical vulnerabilities but also the strategic implications of such breaches in an era where information is both a tool of statecraft and a battleground for influence. The incident has likely set a precedent for how similar cases will be handled in the future, with an emphasis on prevention, rapid response, and the international coordination of cybersecurity efforts.

Case 7: Sinovel Wind Group

In the realm of technology theft, the case involving the Chinese wind turbine manufacturer Sinovel Wind Group stands out as a stark example of corporate espionage with significant economic repercussions. Sinovel, one of China's largest wind turbine makers, was at the center of a legal battle that highlighted the challenges U.S. companies face when their intellectual property is targeted by foreign entities. This case revolved around the theft of proprietary software from American Superconductor Corporation (AMSC), a U.S.-based firm specializing in wind turbine technology.

The relationship between Sinovel and AMSC began as a partnership. AMSC developed sophisticated software that regulated the flow of electricity from wind turbines into electrical grids, crucial for maintaining power stability. This technology, known as Low Voltage Ride Through (LVRT), was licensed by Sinovel for use in its turbines through contracts worth over $800 million. However, in March 2011, the relationship took a dramatic turn when Sinovel abruptly ceased accepting shipments from AMSC and failed to pay for the software, leading to suspicions of foul play.

The espionage was facilitated by an insider at AMSC, Dejan Karabasevic, who was the head of AMSC's automation engineering department in Austria. Karabasevic, after being recruited by Sinovel, stole the source code for the LVRT software from AMSC's systems in Wisconsin, transferring it to Sinovel. He was promised significant financial incentives and was allegedly provided with an apartment in Beijing and other benefits. This theft allowed Sinovel to produce and retrofit turbines with AMSC's technology without further payment or licensing, effectively cutting AMSC out of their business deal.

The impact on AMSC was devastating. The company saw a sharp decline in revenue, losing over $1 billion in shareholder equity and laying off nearly 700 employees, which was more than half of its global workforce. This case was not just about the immediate financial loss but also the long-term damage to AMSC's competitive position in the global wind energy market, as Sinovel could now offer similar technology at potentially lower costs.

The legal response was swift and severe. In June 2013, the U.S. Department of Justice indicted Sinovel and three individuals, including Karabasevic, on charges of conspiracy to commit trade secret theft, theft of trade secrets, and wire fraud. After a trial in 2018, a federal jury in Madison, Wisconsin, convicted Sinovel on all counts, marking one of the few instances where a Chinese company was held accountable in a U.S. court for such crimes. The company was fined the maximum statutory amount of $1.5 million and ordered to pay $57.5 million in restitution to AMSC, highlighting the U.S. justice system's stance on protecting intellectual property.

Beyond the courtroom, the Sinovel case had broader implications for U.S.-China trade relations, intellectual property rights, and the renewable energy sector. It became a focal point in discussions about the enforcement of IP laws internationally and the strategic use of espionage to gain technological advantages. This case was often cited in debates over trade policies, particularly regarding how the U.S. should address the theft of technology by state-backed enterprises or those with close government ties in China.

The incident also underscored the vulnerabilities in global supply chains and partnerships, where technology sharing can turn into a liability if not adequately protected. Companies in high-tech sectors were prompted to reevaluate their security measures, particularly how they manage and protect their intellectual assets when engaging with international partners. The Sinovel case led to a push for more stringent due diligence, better legal frameworks to protect against IP theft, and enhanced monitoring of technology transfers.

Finally, the Sinovel case served as a cautionary tale about the risks of doing business in sectors where state interests might conflict with commercial ones. It emphasized the need for companies to have robust cybersecurity protocols, legal safeguards, and contingency plans for intellectual property protection. This case has influenced how U.S. firms approach international collaborations, especially with entities in countries known for aggressive technology acquisition strategies, fostering a more cautious and defensive corporate culture in terms of IP management and international business dealings.

(Pictured above: A wind turbine from the Sinovel Wind Group)

Methods and Techniques

In the domain of espionage, particularly when it comes to technology theft, China has utilized a multifaceted approach that includes cyber espionage, human intelligence (HUMINT), and leveraging legal and economic frameworks to achieve its goals.

Cyber Espionage entails a range of sophisticated hacking campaigns aimed at stealing sensitive information. One prevalent technique is the use of Advanced Persistent Threats (APTs), where attackers maintain a long-term presence within a network to extract valuable data over time. Operations like those attributed to groups like APT1 (Unit 61398) or APT10 showcase the depth of these campaigns. They often begin with spear-phishing emails targeting specific individuals within an organization, tricking them into revealing credentials or downloading malicious attachments. Once inside, attackers deploy custom-made malware, such as backdoors or remote access trojans, to navigate through the network, escalating privileges to access high-value data like source code, R&D documents, or strategic business plans. Data breaches are often the endgame, where large volumes of data are exfiltrated silently over time, with attackers sometimes even manipulating data to mislead competitors or gain market advantages.

Human Intelligence (HUMINT) plays a crucial role in espionage by leveraging human elements to gather information. This involves the recruitment of insiders, where individuals within targeted organizations are approached, often through personal connections or under the guise of career advancements. The case of Dongfan "Greg" Chung at Boeing illustrates how someone can be cultivated over decades to pass on sensitive information. Academic collaborations offer another vector; Chinese intelligence might sponsor or directly invite experts to China under academic exchanges, where they can be covertly assessed for recruitment or directly asked to share proprietary knowledge. This method was notably used by Yanjun Xu in his operations targeting GE Aviation. Business ventures, too, are exploited where Chinese companies might establish joint ventures with foreign firms, allowing them to get close to proprietary technologies. Here, the line between legitimate business practices and espionage can blur, as seen in the Sinovel vs. AMSC case where an insider was pivotal in technology theft.

Legal and Economic Leverage represents a more systemic approach to technology acquisition. China has utilized its regulatory framework to exert pressure on foreign companies, often through mandatory joint ventures or technology transfer requirements for market access. For instance, foreign companies looking to enter or expand in the Chinese market are sometimes forced to share technology with local partners, which can lead to technology leakage. This was particularly evident in sectors like automotive, where foreign manufacturers had to partner with Chinese companies, resulting in technology transfer agreements that benefited Chinese firms. Additionally, regulatory pressures, including stringent cybersecurity reviews, can be used to access source code or other sensitive data under the pretext of national security checks. This method was highlighted in discussions around companies like Huawei and their potential role in espionage, where regulatory compliance in China might serve as a means to access proprietary information.

The combination of these methods forms a comprehensive strategy for espionage that is hard to counter due to its layered approach. Cyber espionage provides the speed and anonymity to steal vast amounts of data quickly, while HUMINT offers the subtlety and depth of understanding human behavior and motivations, which can lead to long-term intelligence gains. Legal and economic leverage, on the other hand, operates under the guise of lawful commercial and regulatory practices, making it challenging for foreign entities to resist without risking market access or engaging in costly legal battles.

The effectiveness of these methods is amplified by China's state-backed approach, where national strategies like "Made in China 2025" explicitly aim to elevate China in global high-tech industries. This alignment of espionage activities with national policy goals means that there is significant state support, including funding, legal protection, and operational cover, for those involved in these activities.

Countering these methods requires not just technical cybersecurity measures but also a strategic approach to international business and diplomacy. Companies must have robust internal security policies, regularly train employees on espionage risks, and conduct due diligence on partners and suppliers. Governments, on their part, have responded with policies like export controls, investment scrutiny, and international treaties aimed at protecting intellectual property and ensuring fair trade practices.

However, the global nature of business and the integration of supply chains mean that completely eliminating these threats is challenging. The ongoing evolution of technology, including advancements in AI and the Internet of Things, introduces new vulnerabilities that could be exploited. This necessitates a continuous adaptation of defense strategies, emphasizing not just protection but also resilience against the inevitable breaches that do occur.

In essence, China's methods and techniques in espionage are comprehensive, combining advanced cyber operations, human intelligence, and economic strategies to achieve its technological and strategic objectives. This approach has significant implications for global economic security, intellectual property rights, and international relations, prompting a reevaluation of how nations and corporations safeguard their innovations in an increasingly interconnected world.

Impact on the US

The impact of Chinese espionage on the United States has been profound, affecting its economy, national security, and leading to significant policy responses aimed at mitigating these threats.

Economic Impact has been one of the most direct and measurable consequences. The theft of intellectual property by Chinese entities has cost the U.S. economy billions of dollars annually. Estimates suggest that the financial impact ranges from $225 billion to $600 billion each year, encompassing the costs of counterfeit goods, pirated software, and outright theft of trade secrets. This loss of IP directly undermines American companies' ability to innovate and maintain market competitiveness. When proprietary technology is stolen, companies not only lose the financial investment in R&D but also see their competitive edge eroded as Chinese firms can produce similar products at lower costs or faster, capturing market share that might have gone to U.S. firms. This has led to job losses, particularly in sectors like manufacturing, where companies like American Superconductor Corp. felt the brunt after Sinovel's theft of their technology, leading to significant layoffs. The broader economic impact includes a potential decrease in investment in innovation due to the risks associated with IP theft, affecting long-term growth and technological leadership.

National Security faces threats from this espionage in multiple dimensions. Military technology has been a prime target, with cases like those involving nuclear secrets, aerospace technology, and cyber capabilities showing how such theft can compromise U.S. defense advantages. For instance, the espionage involving Dongfan "Greg" Chung at Boeing not only affected commercial aviation but also military projects, potentially aiding Chinese military advancements. The theft of military technology can lead to direct threats if adversaries can replicate, counter, or use that technology against U.S. interests. Strategic industries, such as telecommunications and energy, are also at risk. The Super Micro Computer Inc. incident, where hardware was allegedly compromised, highlighted vulnerabilities in supply chains critical to national infrastructure. This can extend to civilian sectors where technology with dual-use potential (civilian and military applications) is stolen, blurring the line between economic espionage and threats to national security. Overall, these activities challenge the integrity and reliability of U.S. security infrastructure, from cyber to physical, necessitating constant vigilance and adaptation.

Policy Responses by the U.S. government have been multifaceted, aiming to address both the symptoms and root causes of Chinese espionage. One significant response was the launch of the China Initiative by the Department of Justice in 2018, explicitly targeting Chinese economic espionage and theft of trade secrets. This initiative aimed to prosecute not only individual actors but also to hold Chinese companies accountable through various legal means. However, the initiative faced criticism for potentially racial profiling and was eventually scaled back or re-evaluated in 2022 due to these concerns and its effectiveness.

Another response has been through export controls, where the U.S. has tightened regulations on technology transfers to China, particularly in areas deemed critical to national security or economic competitiveness. The Entity List, managed by the Department of Commerce, has seen an increase in Chinese companies, including tech giants like Huawei, making it harder for them to acquire U.S. technology or components. The CHIPS Act passed in 2022, aimed at bolstering domestic semiconductor production, is a direct response to the risks posed by reliance on foreign manufacturers, particularly in light of espionage concerns.

Legislation like the Foreign Investment Risk Review Modernization Act (FIRRMA) of 2018 has also expanded the powers of the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States (CFIUS) to scrutinize foreign investments, especially from China, that might pose a risk to national security. This includes looking into transactions that could lead to technology transfer or control over sensitive technology.

In response to cyber threats, the U.S. has also pursued strategies like cyber diplomacy, international agreements to curb cyber espionage, and enhancing cyber defenses for both government and private sector infrastructure. The Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA) has played a pivotal role in coordinating these efforts, sharing threat intelligence, and advising on cybersecurity practices.

Moreover, there has been a push for greater collaboration between government and industry, encouraging companies to report cyber intrusions, share data on threats, and invest in cybersecurity. This includes incentives for companies to adopt best practices in cybersecurity and to diversify supply chains to reduce dependency on potentially risky foreign suppliers.

In summary, the impact of Chinese espionage on the U.S. has prompted a broad spectrum of policy responses aimed at protecting economic interests, national security, and fostering an environment where innovation can thrive without the constant threat of theft. However, the challenge remains ongoing, requiring continuous adaptation and vigilance as espionage techniques evolve and geopolitical tensions fluctuate.

International Reactions and Countermeasures

The incidents of Chinese industrial espionage have not only had domestic repercussions within the United States but have also significantly influenced international relations, particularly between the U.S. and China, and prompted a range of countermeasures globally.

Diplomatic tensions between the U.S. and China have been palpably strained by espionage allegations. Over the years, each new case of espionage has added layers to the complex bilateral relationship, often overshadowing economic, trade, or strategic dialogues with security concerns. For instance, the indictment of Chinese military officers for hacking into U.S. companies in 2014 marked a significant escalation, leading to official protests from China and a sharp exchange of diplomatic rhetoric. These incidents have contributed to a cycle of tit-for-tat actions, including U.S. sanctions or legal actions against Chinese entities, which China often counters with its own measures or denials, accusing the U.S. of similar activities. Such events have fostered a climate of mistrust, making diplomatic engagements more about managing tensions rather than fostering cooperation.

The strain has also infiltrated economic discussions, where espionage is often cited in U.S. arguments for imposing tariffs, trade restrictions, or investment reviews, particularly under the Trump and Biden administrations. These actions are not only about protecting U.S. interests but also serve as diplomatic signals of resolve against perceived threats from China, complicating negotiations on broader issues like climate change, international trade, or regional security in the Asia-Pacific.

Global response to Chinese espionage has varied but has increasingly shown a pattern of concern and counteraction across different countries. European nations, for example, have experienced espionage involving intellectual property and strategic sectors like telecommunications, automotive, and pharmaceuticals. Germany, for instance, has been vocal about the threat, especially in light of cases involving automotive technology or the security implications of using Huawei equipment for 5G networks. The European Union has responded with initiatives like the EU Cybersecurity Act, aiming to enhance cybersecurity resilience across member states and encouraging a more coordinated approach to countering state-sponsored cyber threats.

In Australia, the discovery of Chinese-linked cyber operations targeting political parties, universities, and critical infrastructure has led to stringent foreign investment laws and cybersecurity strategies. Australia's response includes the establishment of the Australian Signals Directorate's Cyber Security Centre, which works closely with private sector partners to defend against such threats.

Canada has also faced espionage, with notable cases involving Chinese efforts to influence Canadian politics or the targeting of intellectual property in academia and industry. This has prompted a reevaluation of security clearance processes, increased scrutiny over foreign investments, and more robust counterintelligence measures.

Collectively, these nations, along with others like Japan and India, have begun to take part in or push for international frameworks to combat espionage. The Five Eyes intelligence alliance (comprising Australia, Canada, New Zealand, the United Kingdom, and the United States) has been particularly active in sharing intelligence on threats from China, advocating for a coordinated response that might include sanctions, legal actions, or diplomatic efforts to pressure China into altering its espionage practices.

On a broader scale, therehas been a push for international norms in cyberspace, with organizations like the United Nations attempting to draft cyber norms that would, among other things, address state-sponsored espionage. However, these efforts are complicated by differing national interests and the challenge of enforcing such norms without the full cooperation of all major powers, including China.

Moreover, there has been a growing trend towards "de-risking" strategies in global business, where countries and companies look to reduce dependency on Chinese technology or manufacturing to mitigate espionage risks. This includes diversifying supply chains, increasing domestic production capabilities, particularly in critical technologies, or partnering with allies for technology development and sharing.

In sum, the international reaction to Chinese espionage has been characterized by increased vigilance, legislative and policy changes, and a shift towards collective security measures. While diplomatic tensions between the U.S. and China highlight the most pronounced friction, the global response reflects a broader consensus on the need for enhanced security, cooperation in cyber intelligence, and a rethinking of economic ties with China in light of these espionage activities. However, achieving a cohesive, effective international strategy remains challenging due to the geopolitical complexities and the inherent nature of espionage, which often operates in the shadows of international law and diplomacy.

US Industrial Espionage Against China

The question of whether the United States engages in industrial espionage similar to what has been attributed to China is nuanced, involving historical context, legal frameworks, and official policy statements. While the U.S. government and its intelligence agencies are known for their capabilities in espionage, particularly in military and national security domains, the public record and official stance regarding industrial espionage on China are different in several key respects.

Historically, the U.S. has indeed engaged in intelligence gathering, but the focus has traditionally been on military, political, and strategic information rather than purely industrial secrets for commercial gain. During the Cold War, for example, much of the espionage was aimed at understanding Chinese military capabilities, technological advancements, and political intentions. This pattern largely continued post-Cold War, with U.S. intelligence operations focusing on threats from terrorism, proliferation of weapons of mass destruction, and geopolitical rivals like Russia and China, not on stealing trade secrets for American companies to gain a market advantage.

The U.S. has legal frameworks and policies that explicitly prohibit government agencies from engaging in industrial espionage for the benefit of private companies. The Economic Espionage Act of 1996 criminalizes the theft of trade secrets, whether for foreign governments or for economic gain in the U.S. This act was designed to protect U.S. companies from espionage but also to ensure that the U.S. government itself does not partake in such activities. Agencies like the CIA or NSA are bound by these laws, focusing their missions on national security rather than commercial interests.

Despite this, there have been allegations and claims from China and other countries suggesting U.S. involvement in economic espionage. For instance, China has accused the U.S. of cyber espionage, citing incidents like the Edward Snowden leaks, which revealed extensive NSA surveillance programs. However, these allegations generally involve gathering data that could have both military and economic implications, such as insights into technology development that might have dual-use applications, rather than purely industrial benefits.

The tactics used by the U.S. in intelligence gathering that might resemble industrial espionage include:

Cyber Operations: The NSA has been reported to engage in cyber activities that gather vast amounts of data, including from private sector companies, though this is primarily justified under the banner of national security, counterterrorism, or counterproliferation. The focus here is not on stealing corporate secrets for direct commercial use but on understanding technological capabilities for strategic purposes.

Human Intelligence (HUMINT): While the U.S. does recruit insiders or leverage business and academic collaborations for intelligence, these efforts are generally aimed at understanding foreign political, economic, or military strategies rather than acquiring trade secrets for economic benefit.

Legal and Economic Leverage: Unlike China's reported use of forced technology transfers through joint ventures, U.S. policy has moved towards encouraging open trade and investment, albeit with increased scrutiny on security grounds. U.S. companies benefit from a more open market access strategy, but this is not backed by government-led espionage.

What sets the U.S. apart in this context is the transparency and accountability in its legal system. When U.S. companies are caught engaging in espionage or when there are allegations of such activities, they can be prosecuted. For instance, the case of Marc Rich, who was indicted for trading with Iran during the U.S. embargo, shows that even high-profile business figures are not immune to legal repercussions if they engage in activities that could be construed as espionage or illegal trade practices.

In recent years, the U.S. has also taken steps to differentiate itself by promoting international norms against cyber espionage for commercial gain. Agreements like the one made during the U.S.-China summit in 2015, where both nations agreed not to conduct or knowingly support cyber-enabled theft of intellectual property, illustrate this commitment, even if compliance has been questioned.

In conclusion, while the U.S. does possess the capability for sophisticated intelligence operations, including those that could theoretically be used for industrial espionage, the official policy, legal framework, and historical focus of U.S. intelligence activities suggest a different approach from what has been attributed to China. The U.S. targets are more aligned with national security, strategic interests, and countering threats rather than directly stealing industrial secrets for commercial advantage. However, the opaque nature of intelligence operations means that absolute certainty on this matter is elusive, and perceptions or sporadic cases might exist that challenge this narrative.

Conclusion:

The scope and scale of Chinese industrial espionage against the United States illustrate a multifaceted and persistent challenge to national security, economic stability, and intellectual property rights. These activities, ranging from cyber intrusions to human intelligence operations and exploitation of economic frameworks, highlight the strategic rivalry between the two nations. Through landmark cases such as Operation Aurora, the Sinovel Wind Group incident, and Unit 61398's cyber campaigns, it becomes evident that industrial espionage is not merely an issue of corporate competitiveness but a tool of statecraft used to advance national objectives and commercial economic gain (profit).

The profound impacts on the U.S. include significant financial losses, compromised technological leadership, and vulnerabilities in critical infrastructure. These consequences have prompted robust policy responses, including tightened export controls, enhanced cybersecurity measures, and a reevaluation of economic partnerships with China. At the same time, these incidents have deepened geopolitical tensions, complicating diplomatic relations and trade negotiations.

The international community's growing awareness of the threat has led to collaborative countermeasures, including intelligence sharing among allies and the establishment of global cybersecurity norms. However, as espionage techniques evolve and geopolitical landscapes shift, the challenge of safeguarding intellectual property and national security remains a dynamic and ongoing endeavor.

Ultimately, addressing industrial espionage requires a multifaceted approach that combines technological innovation, legal enforcement, and strategic diplomacy. For the United States, maintaining its competitive edge and protecting its intellectual assets will depend on the continued adaptation and strengthening of both domestic and international safeguards, ensuring that its industries remain resilient in the face of emerging threats.

Sources:

Center for Strategic and International Studies. (2000). Survey of Chinese espionage in the United States. CSIS. https://www.csis.org/programs/strategic-technologies-program/survey-chinese-espionage-united-states-2000

Kharpal, A. (2020, September 3). Timeline: A history of Chinese espionage and trade secret theft in the U.S. MIT Technology Review. https://www.technologyreview.com/2020/09/03/1007609/trade-secrets-china-us-espionage-timeline/

BBC News. (2023, January 17). China's economic espionage: A growing threat. BBC. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-china-64206950

Comey, J. (2014, July 7). Responding effectively to the Chinese economic espionage threat. FBI. https://www.fbi.gov/news/speeches/responding-effectively-to-the-chinese-economic-espionage-threat

U.S. Department of Justice. (2014, May 19). U.S. charges five Chinese military hackers for cyber espionage against U.S. corporations and labor organizations. U.S. Department of Justice. https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/us-charges-five-chinese-military-hackers-cyber-espionage-against-us-corporations-and-labor

BBC News. (2023, January 17). China's economic espionage: A growing threat [AMP version]. BBC. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-china-64206950.amp

Freethink. (n.d.). Chinese industrial espionage. Freethink. https://www.freethink.com/the-changing-world-order/chinese-industrial-espionage

Zakaria, F. (2019, August 19). Inside the U.S.-China espionage war. The Atlantic. https://www.theatlantic.com/politics/archive/2019/08/inside-us-china-espionage-war/595747/

Mozur, P. (2023, March 7). China's spying on U.S. technology. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2023/03/07/magazine/china-spying-intellectual-property.html

BBC News. (2023, January 17). China's economic espionage: A growing threat [AMP version]. BBC. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-asia-china-64206950.amp

Feng, A. (2023, March 28). China has been waging a decades-long, all-out spy war. Foreign Policy. https://foreignpolicy.com/2023/03/28/china-has-been-waging-a-decades-long-all-out-spy-war/

Gady, F. S. (2018, November 7). Uncovering Chinese espionage in the U.S. The Diplomat. https://thediplomat.com/2018/11/uncovering-chinese-espionage-in-the-us/

Center for Strategic and International Studies. (n.d.). How the Chinese Communist Party uses cyber espionage to undermine the American economy. CSIS. https://www.csis.org/analysis/how-chinese-communist-party-uses-cyber-espionage-undermine-american-economy

House Committee on Homeland Security. (2024, September 16). What they are saying: Joint investigation finds potential Chinese espionage threats to U.S. ports. Homeland Security Committee. https://homeland.house.gov/2024/09/16/what-they-are-saying-joint-investigation-finds-potential-chinese-espionage-threats-to-u-s-ports/

Kharpal, A. (2021, December 2). The end of the China Initiative: How the U.S. Justice Department's program to counter Chinese espionage fizzled out. MIT Technology Review. https://www.technologyreview.com/2021/12/02/1040656/china-initative-us-justice-department/

Sanger, D. E., & Barnes, J. E. (2023, October 18). China's new spying tactics target U.S. technology. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2023/10/18/us/politics/china-spying-technology.html

Center for Strategic and International Studies. (2000). Survey of Chinese espionage in the United States. CSIS. https://www.csis.org/programs/strategic-technologies-program/survey-chinese-espionage-united-states-2000

Comey, J. (2014, July 7). Responding effectively to the Chinese economic espionage threat. FBI. https://www.fbi.gov/news/speeches/responding-effectively-to-the-chinese-economic-espionage-threat

BBC News. (2023, January 17). China's economic espionage: A growing threat. BBC. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-china-64206950

Goldman, D. (2014, May 20). U.S. accuses China's military of hacking. CNN. https://www.cnn.com/2014/05/20/world/asia/china-unit-61398/index.html

Mullen, J. (2014, May 20). China-U.S. cyber spying row turns spotlight back on shadowy Unit 61398. Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-cybercrime-usa-china-unit/china-u-s-cyber-spying-row-turns-spotlight-back-on-shadowy-unit-61398-idUSBREA4J08M20140520/