China’s Role in the Global Arms Trade: An Analysis of Arms Exports and Their Geopolitical Implications

From Buyer to Supplier: China's Transformation in the Arms Market

(Pictured above: Philippine Defense Secretary Delfin Lorenzana (left), Chinese Ambassador to the Philippines Zhao Jianhua, and Philippine Armed Forces Chief Gen. Eduardo Ano (right) inspect Chinese-made CQ-A5b assault rifles 5 October 2017 during a turnover ceremony at Camp Aguinaldo in Quezon City, Philippines. The weapons and ammunition are part of China’s military donation to the Philippines’ fight against Muslim militants who laid siege to Marawi in southern Philippines. (Photo by Bullit Marquez, Associated Press))

TL; DR:

Transformation to a Leading Exporter

China evolved from a major arms importer to one of the top five global arms exporters.

Advances in technology and state support have fueled this growth.

Strategic Motivations Behind Arms Exports

Bolsters China's economy while expanding its geopolitical influence.

Strengthens alliances, counters Western influence, and secures resources.

Aligns arms sales with broader initiatives like the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI).

Key Markets and Export Focus

Major buyers include Pakistan, Bangladesh, African nations, and Middle Eastern countries.

Offers cost-effective, competitive military equipment like drones, naval ships, and missile systems.

State-Driven Industry

Dominated by state-owned enterprises (e.g., NORINCO, AVIC).

Integration of military and civilian technology enhances production and innovation.

Geopolitical Implications

Reinforces alliances (e.g., with Pakistan) and influences regional conflicts.

Provides leverage in areas like the South China Sea and Africa through arms and infrastructure deals.

Challenges traditional arms exporters like the U.S. and Russia.

Criticisms and Challenges

Concerns over quality and reliability of Chinese arms persist.

Arms sales to regimes with poor human rights records attract international criticism.

Lack of robust after-sale support affects buyer satisfaction.

Future Trends

Focus on emerging technologies like AI, cyber warfare, and space systems.

Expansion into new markets and deeper ties with existing ones.

Potential influence on global arms control norms and regional power dynamics.

Strategic Risks

Over-reliance on arms exports for influence could backfire if quality or political risks escalate.

Competition with established exporters and shifting global alliances pose challenges.

Broader Impact

China's arms trade serves as a tool for reshaping global geopolitics, challenging U.S. dominance, and influencing regional stability.

Its long-term success depends on navigating quality concerns, market competition, and international norms.

And now for the Deep Dive...

Introduction

China has significantly transformed its role within the global arms market over the past few decades, moving from primarily an importer to one of the world's leading arms exporters. Historically, China's military-industrial complex was focused on equipping the People's Liberation Army, but with economic reforms and technological advancements, the nation began to seek broader markets for its defense products. Today, China is recognized as one of the top five arms exporters globally, contributing to a diverse array of military equipment including drones, ships, and ballistic missiles, which are increasingly competitive with Western offerings in terms of price and, in some cases, technology.

The purpose of this article is to delve into how China's burgeoning arms export industry impacts global geopolitics. By selling arms, China not only bolsters its economy but also expands its strategic influence, particularly in regions where it seeks to counterbalance American and European influence. This analysis aims to unpack the nuanced ways in which arms sales are used as a geopolitical tool by Beijing, from fostering alliances to securing natural resources and influencing internal politics of recipient countries. It seeks to provide a comprehensive understanding of how these exports affect international relations, regional stability, and the broader security landscape.

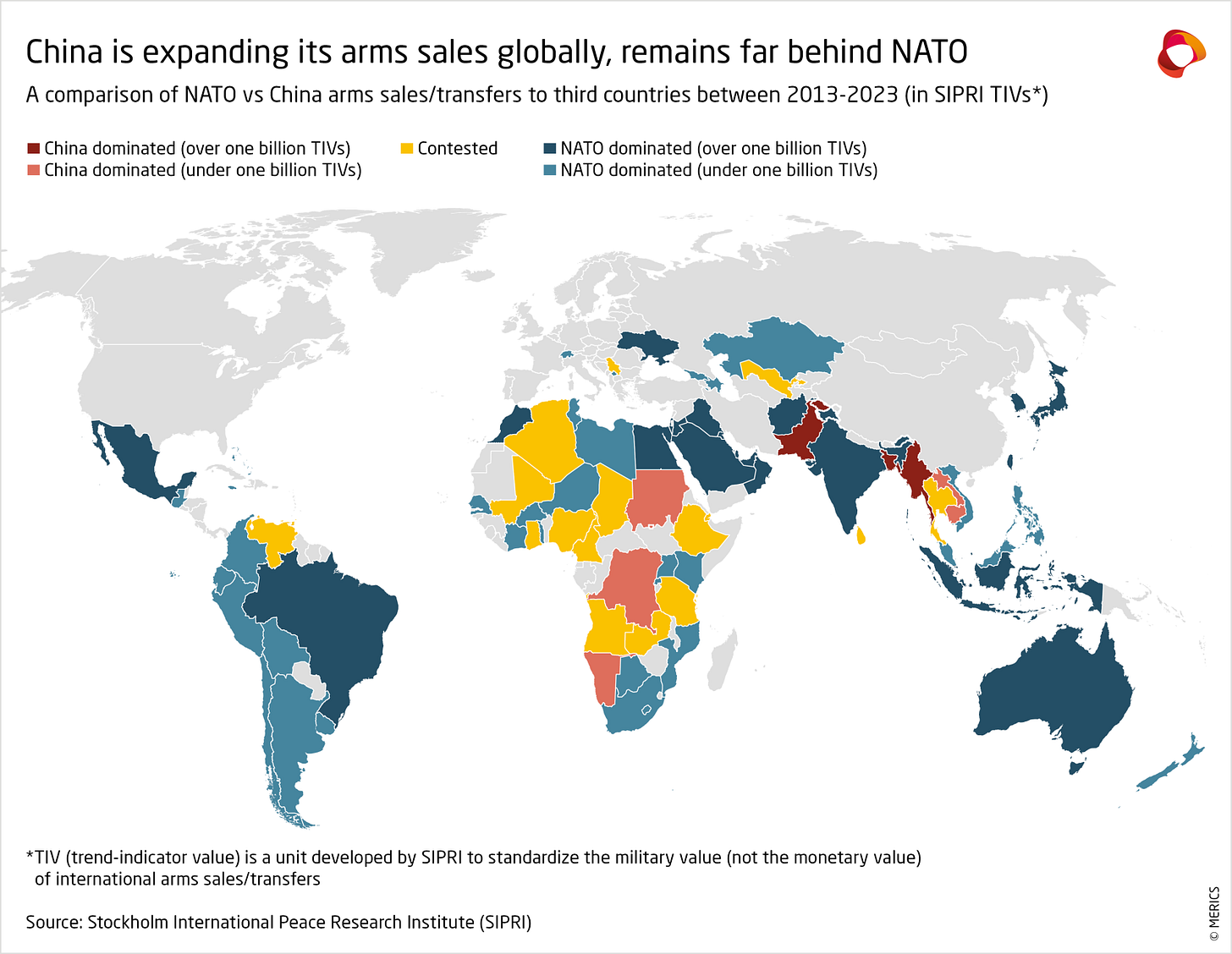

To undertake this analysis, the article relies on a wide array of data sources including the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI) arms transfer databases, various trade reports, and geopolitical analyses from think tanks and scholars. SIPRI, in particular, provides detailed, annual assessments of arms transfers that are crucial for understanding trends and patterns in China's export activities. The methodology adopted here involves examining these data sets in conjunction with qualitative geopolitical assessments to draw connections between arms sales and strategic outcomes, with a focus on the economic, political, and security implications of China's actions in the arms trade.

The scope of this study encompasses not only the immediate economic benefits to China from arms sales but also the long-term strategic positioning these sales facilitate. By analyzing specific case studies, such as arms sales to Pakistan or various African nations, the article will explore how these transactions align with broader Chinese foreign policy objectives like the Belt and Road Initiative. This approach provides a critical lens to assess how China's arms export strategy might reshape global alliances, influence regional conflicts, and possibly challenge the existing international arms control regimes.

(Pictured above: The Pakistani army tests Chinese-made weapon systems including the A-100 Multiple Barrel Rocket Launcher, the SLC-2 weapons locating radar, and VT-4 tanks during military exercise Azm-E-Nau in 2009. These weapons systems were later adopted into the Pakistani military. Over the past decade, China has supplanted the United States as Pakistan’s largest arm supplier. (Photo courtesy of the Inter-Services Public Relations Pakistan))

The Growth of China's Arms Export Industry

The growth of China's arms export industry marks a significant shift in global military economics, reflecting the country's strategic ambitions and industrial capabilities. In the 1990s, China was predominantly an arms importer, largely reliant on Soviet and later Russian technology to modernize its military. However, the turn of the millennium saw a strategic pivot towards self-sufficiency and export. This was driven by reforms under Deng Xiaoping, which prioritized the development of a robust defense industry as one of the "four modernizations." This era laid the groundwork for what would become a formidable arms export sector, with key milestones including the development of indigenous military technology and the expansion of manufacturing capabilities.

By the early 21st century, China had not only reduced its dependability on foreign arms but also began to show prowess in exporting a wide variety of military equipment. Today, China's current arms exports include advanced drones, naval ships, armored vehicles, and various missile systems. These products have found markets in regions where cost-effectiveness and less stringent political conditions are valued. In Asia, countries like Pakistan and Bangladesh are significant buyers, with Pakistan receiving a vast majority of China's military exports. In Africa, China has penetrated markets in nations like Ethiopia and Nigeria, offering equipment that competes with Western suppliers on price. The Middle East, particularly countries seeking to diversify their military suppliers away from traditional Western sources, has also seen an influx of Chinese arms, while in Latin America, Venezuela and Bolivia have been notable recipients.

The economic backbone of China's arms export success lies in its state-owned enterprises (SOEs). Companies like the Aviation Industry Corporation of China (AVIC), China North Industries Group Corporation (NORINCO), and China State Shipbuilding Corporation (CSSC) dominate both domestic production and international sales. These entities enjoy substantial government backing, which allows for large-scale production, competitive pricing, and extensive R&D investment. Additionally, the Chinese government's policy of integrating civilian and military technology development has bolstered the capacity of these SOEs, enabling them to produce dual-use technologies that can be adapted for military applications.

Technological advancements have been pivotal in transforming China from an exporter of basic, often reverse-engineered, weapons to one that offers increasingly sophisticated systems. Early on, China leveraged reverse-engineering to catch up with global standards, particularly with Soviet and Russian designs. Over time, however, the focus shifted towards innovation, especially in areas like unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) where China has become a global leader. The development of indigenous technology, such as the Beidou navigation system and advances in cyber warfare capabilities, has also played a role in enhancing the quality and appeal of Chinese military exports. This technological progress is not without its challenges, as quality control and reliability issues persist, but it has undeniably propelled China into the international arms market.

The strategic implications of China's arms exports are manifold, influencing international relations, regional security dynamics, and even global arms control norms. By providing arms to countries with which it seeks to strengthen ties, China often secures not only economic benefits but also political leverage. For instance, in regions like Southeast Asia, military sales are part of a broader strategy to assert influence in the South China Sea, challenging U.S. dominance. In Africa, arms sales are intertwined with resource extraction rights, infrastructure projects, and diplomatic recognition, notably in the context of China's Belt and Road Initiative.

Moreover, China's arms export strategy often involves selling to countries under international sanctions or those with controversial human rights records, which has raised concerns about the potential for these weapons to exacerbate conflicts or support authoritarian regimes. This approach contrasts with the more conditional sales practices of Western countries, where human rights and political stability often influence export decisions. However, this less conditional approach has also made China a preferred supplier in markets where access to Western or Russian arms is limited.

Economic factors within China further complicate the arms export landscape. The defense industry is seen as a crucial component of economic development, providing jobs, fostering technological innovation, and contributing to GDP. The global arms market provides a venue for these enterprises to scale up production and reduce costs through economies of scale, which in turn benefits domestic military modernization efforts.

However, the reliance on foreign markets for arms sales introduces vulnerabilities. Fluctuations in international demand, economic sanctions, or shifts in geopolitical alliances could impact China's defense industry. Additionally, as China's military technology advances, there's an ongoing debate about whether to prioritize domestic military capabilities over exports, especially in light of increasing regional tensions and strategic competition with the U.S. and its allies.

Geopolitical Implications of China's Arms Exports

The geopolitical implications of China's arms exports are particularly pronounced in Asia, where Beijing has leveraged its military sales to strengthen strategic alliances and expand its influence. China's close relationship with Pakistan is emblematic of this strategy, with Pakistan receiving nearly half of China's total arms exports. This includes sophisticated weaponry like fighter jets and naval vessels, which not only bolster Pakistan's military capabilities but also serve as a counterbalance to India, China's regional rival. Similarly, engagements with Bangladesh and Myanmar have deepened, providing China with strategic footholds in key maritime routes and land borders. These alliances not only enhance China's security posture but also affect regional security dynamics, notably in the South China Sea, where arms sales contribute to military build-ups that can challenge the U.S. and its allies.

In the South China Sea, China's export of military hardware has direct implications for territorial disputes and maritime security. By arming and training the militaries of surrounding nations, China not only secures allies but also potentially deters these countries from aligning with U.S. interests. The provision of surveillance equipment, submarines, and patrol vessels to countries like Vietnam or the Philippines, despite their disputes with China, serves as a double-edged sword, ensuring that these nations remain economically tethered to China while providing them with means to enforce their maritime claims, which could lead to increased tensions or a negotiated status quo that favors China.

Turning to Africa, China's expansion of arms exports has significantly increased its market share in Sub-Saharan Africa, where about 70% of armies now use Chinese equipment. This trend is not merely about selling arms but about securing political influence and access to natural resources. Arms sales often accompany infrastructure deals or resource extraction agreements, ensuring that African countries view China as a strategic partner. However, this involvement has raised concerns about the stability of the region. The proliferation of Chinese weapons can either stabilize or destabilize nations, depending on how these arms are integrated into local power structures, potentially fueling conflicts or supporting authoritarian regimes, thus affecting the political landscape.

The implications for African political stability are intricate. On one hand, China's arms can help nations combat insurgencies or terrorist groups, enhancing security. On the other, the same arms can be used in civil conflicts or by governments to suppress opposition, leading to human rights abuses. This dual-edged impact means that while China gains influence, the long-term effects on governance, democracy, and conflict resolution in Africa are mixed, with potential for both positive and negative outcomes.

In the Middle East, China's arms sales strategy is a delicate balancing act among competing regional powers. China has sold arms to Iran, which is under significant Western sanctions, offering an alternative to Russian supplies. Conversely, China also sells to Saudi Arabia and the UAE, key U.S. allies, showcasing its ability to navigate between Sunni and Shia blocs. This strategy not only diversifies China's export markets but also positions it as a neutral player capable of brokering peace or at least maintaining a strategic ambiguity beneficial to its interests. However, this approach risks entanglement in regional conflicts, as weapons could end up on both sides of a conflict, potentially exacerbating tensions.

The Middle Eastern engagement also highlights China's interest in energy security and geopolitical leverage. By arming both sides in the region, China secures influence without overtly choosing sides, thus ensuring access to oil and gas resources while promoting its vision of a multipolar world where its role is significantly amplified. This can lead to a reconfiguration of alliances and security arrangements, with implications for global peace and the stability of oil markets.

In Latin America, China's arms exports have been less about volume and more about strategic positioning, especially in countries like Venezuela and Bolivia. These sales have geopolitical implications, particularly in altering U.S. influence in its traditional backyard. China's engagement with these nations often comes with broader economic packages, including loans and infrastructure projects, creating dependencies that can shift regional power dynamics. By providing arms, China not only gains favor with governments that are often at odds with the U.S. but also establishes itself as an alternative to American military support, thus challenging the established security architecture in the Americas.

The potential for altering U.S. influence in Latin America via arms sales is significant. For instance, Venezuela has used Chinese military hardware to bolster its defense capabilities amidst economic sanctions and political isolation from Western countries. This has not only provided Venezuela with critical military support but also deepened the Sino-Venezuelan relationship in a way that could reshape regional politics, affecting U.S. strategic interests, particularly in terms of energy security and anti-drug operations.

However, the influence China gains through these exports is not without its challenges. In each region, from Asia to Latin America, there are risks associated with arming nations that might later find themselves in conflict or political upheaval, potentially dragging China into international disputes or tarnishing its image as a responsible global player. Additionally, the quality and reliability of Chinese arms have sometimes been questioned, which could lead to backlash or loss of market share if not addressed.

Moreover, the strategic use of arms exports by China often intersects with broader initiatives like the Belt and Road, where military aid can secure infrastructure or resource deals. This integration of military and economic strategy underscores China's comprehensive approach to global influence, but it also means that any shift in one sector can impact the other, creating a complex matrix of diplomatic, economic, and security dependencies.

China's arms exports are a tool of its broader foreign policy, aimed at reshaping global geopolitics in its favor. This involves not just immediate commercial gains but also the long-term strategic positioning of China on the world stage, often at the expense of Western, particularly U.S., influence. The implications are vast, affecting regional and global security, economic dependencies, and the balance of power in international relations.

Challenges and Limitations

One of the primary challenges facing China's arms export industry is the persistent concern over the quality and reliability of its military hardware. Historically, Chinese weapons were often criticized for their lack of durability and operational reliability, issues that trace back to the times when China was reverse-engineering Soviet designs without fully mastering the technology. Even today, while significant strides have been made in the sophistication of Chinese military technology, there are still reports of systems failing prematurely or not performing as advertised. For instance, countries like Iraq and Algeria have experienced operational issues with Chinese drones, leading to crashes and subsequent grounding of fleets.

Comparatively, when set against the arms from the United States or Russia, Chinese weapons often find themselves at a disadvantage in terms of quality. U.S. weapons are renowned for their technological edge and extensive after-sale support, including training and maintenance services, which are crucial for maintaining operational readiness. Russian arms, while sometimes lacking in cutting-edge technology, benefit from a reputation for ruggedness and reliability in harsh conditions. Chinese manufacturers, on the other hand, are noted for providing less support post-sale, which can lead to buyer dissatisfaction, especially in scenarios where immediate technical assistance is required. This gap in service and perceived reliability affects China's ability to penetrate high-end markets and retain long-term customers.

Another significant challenge is tied to China's approach to arms sales regarding political strings and human rights considerations. Unlike many Western nations, which often attach conditions to arms sales related to human rights or democratic governance, China typically sells arms with fewer stipulations. This no-strings-attached policy has allowed China to sell to countries under Western sanctions or those with questionable human rights records, like Sudan, Zimbabwe, or Myanmar. While this strategy has expanded China's market reach, it also attracts criticism and potential geopolitical costs. By arming regimes known for human rights abuses, China risks international condemnation and potential sanctions or diplomatic repercussions.

The geopolitical cost of such sales is multifaceted. On one hand, China gains influence and loyalty from these nations, often securing strategic advantages or resource access in return. On the other, this approach can lead to China being viewed as complicit in human rights violations, potentially damaging its international image and leading to a backlash in public opinion or policy from other nations. There's also the risk of weapons ending up in the wrong hands, further destabilizing regions or contributing to conflicts, which could indirectly impact China's broader foreign policy objectives.

The competitive landscape in the global arms market presents another set of challenges, especially from traditional exporters like the U.S., Russia, and European countries. The U.S. has countered China's rise by enhancing its own technological offerings, focusing on cybersecurity, AI, and integrated systems that offer long-term strategic benefits to allies. Russia, with its established market in regions like the Middle East and Africa, has responded by modernizing its arms to maintain its edge, while also occasionally aligning with China in international forums like the UN to navigate Western pressures.

European countries have taken a more nuanced approach, focusing on niche markets where they can offer high-quality, specialized equipment that complements rather than competes directly with Chinese exports. The saturation of the arms market, with numerous suppliers vying for similar customers, pushes China towards niche specialization, particularly in cost-effective, scalable technologies like drones or cyber warfare tools, where they have shown considerable innovation.

However, this specialization also leads to market saturation in certain areas, where China's low-cost strategy might lead to an oversupply of similar products, reducing the price and profit margins. This saturation can force Chinese companies to explore less lucrative or riskier markets, which might not yield the same strategic benefits as more stable, high-value clients.

Moreover, the strategic response from traditional exporters includes not just direct competition but also diplomatic maneuvers. The U.S., for instance, has used arms sales as leverage in its foreign policy, often linking military support with broader strategic alliances, something China is still learning to balance effectively. This competition has led to a scenario where potential buyers have more options, making them more discerning about the quality, cost, and political implications of choosing Chinese over Western or Russian arms.

China's focus on niche markets also highlights another limitation: the global perception of its arms as being second-tier in terms of innovation and reliability. To overcome this, China must continue to invest heavily in R&D, not just to catch up but to lead in certain tech sectors. However, this is a costly and long-term endeavor, which might not immediately translate into market success given the entrenched positions of competitors.

In terms of after-sale service, another area where China lags, there's a learning curve in building a global service network akin to what Western companies have developed over decades. Without this, China risks losing repeat customers who might prefer the consistent support offered by competitors, even if at a higher initial cost.

Lastly, the geopolitical landscape itself influences China's arms exports. As nations in areas like Southeast Asia or Africa become more cautious of their alignment due to rising tensions with the West, they might opt for a balanced approach in sourcing their military hardware, diluting China's market share. This dynamic requires China to constantly adapt its sales strategy, balancing between aggressive market expansion and the need to maintain a positive international image amid human rights and quality concerns.

Future Trends and Strategic Implications

In terms of future trends, China's arms export industry is likely to see significant growth in areas where technology is rapidly evolving. The integration of artificial intelligence (AI) into military applications is one such frontier. China is actively developing and exporting AI-enhanced weapons systems, including autonomous drones, which can significantly alter modern warfare dynamics. This focus on AI extends to cybersecurity, where China could become a key player by offering sophisticated cyber defense systems, potentially alongside offensive capabilities, catering to nations looking to bolster their digital security. Moreover, space technology, including satellite systems for military use, represents another burgeoning sector where China's advances in the Beidou navigation satellite system could lead to new export opportunities, enhancing the strategic capabilities of buyer nations.

Expansion into new markets or deepening ties in existing ones forms another aspect of China's potential growth strategy. While China has already made inroads in Asia, Africa, and parts of the Middle East, there's room for further penetration, especially in Latin America where geopolitical changes could open new doors. Additionally, deepening relationships in already established markets could involve upgrading the quality and sophistication of arms sold, moving from basic to more advanced systems, thus ensuring repeat business and long-term strategic partnerships. This could be particularly relevant in regions where countries are looking to modernize their military without the political strings attached by Western suppliers.

The impact of China's arms exports on global security is profound, with the potential to shift traditional power balances. As China supplies more advanced and cost-effective military hardware, it might empower smaller nations or non-state actors to challenge regional hegemonies or influence conflicts in new ways. This empowerment could lead to a reconfiguration of alliances, where countries might align more closely with China for security reasons, thereby altering the balance of power, particularly in areas like Southeast Asia or the Middle East. Moreover, the proliferation of Chinese technology could create new security dynamics, where the control over cyberspace or outer space becomes as critical as traditional military domains.

China's increasing role in arms exports also positions it to influence international law and arms control agreements. Traditional frameworks like the Arms Trade Treaty might see new challenges or need amendments as China's non-conditional arms sales could bypass established norms, potentially leading to a more fragmented global approach to arms control. If China continues to ignore or selectively adhere to international norms, it might encourage other nations to do the same, weakening global standards for arms proliferation and control. This scenario would require other major powers to either engage China more constructively in arms control dialogues or seek to counterbalance its influence through new alliances or treaties.

In terms of China's long-term strategy, arms exports are not isolated from its broader geopolitical maneuvers. The Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) exemplifies how military sales can be intertwined with economic and infrastructural projects, creating a network of dependencies that enhance China's strategic position. By aligning arms sales with BRI, China can secure not only military but also political and economic influence in host countries, ensuring their allegiance or at least neutrality in international disputes. This integrated approach uses military exports as a tool to stabilize or influence regions where China has significant investments, thereby supporting its vision of a world order where it plays a central role.

Anticipating changes in global demand for arms is another critical aspect of China's strategy. With ongoing conflicts around the globe, from territorial disputes to civil wars, there's a continuous demand for military hardware. China is well-positioned to meet this demand, particularly in countries undergoing defense modernization but limited by budget constraints. By offering competitive pricing, China can capture markets where cost is a significant factor, thus not only gaining economic benefits but also extending its geopolitical reach. Furthermore, China can predict shifts in demand due to emerging threats like cyber warfare or space militarization, areas where it has invested heavily, thereby staying ahead of market trends.

However, this strategy also involves risks. Over-reliance on arms exports for geopolitical influence might backfire if the quality or reliability of Chinese arms does not meet expectations, leading to a loss of trust or market share. Additionally, as global conflicts evolve, so do the international responses, including sanctions or embargoes, which could affect China's ability to sell arms freely. China must navigate these waters carefully, balancing between aggressive market expansion and the potential backlash from international communities concerned about the spread of weapons or their use in human rights violations.

Finally, China's approach to arms exports will need to adapt to the increasing sophistication of global defense strategies. As nations adapt to new forms of warfare, including hybrid and asymmetric tactics, China's arms industry will have to innovate continuously. This includes not just the weapons themselves but also the strategic use of these exports in broader geopolitical strategies, ensuring that China's military influence supports its vision of a multipolar world where it holds significant sway.

Conclusion

China's role in the global arms trade reflects its broader ambitions as a rising power reshaping the international order. By leveraging its arms exports, Beijing has effectively fused economic, political, and military strategies to extend its influence, challenge Western dominance, and promote its vision of a multipolar world. This transformation from a regional power to a global arms exporter underscores China's remarkable strides in technological innovation, industrial capacity, and strategic foresight.

However, the implications of this growth are complex. While China has successfully penetrated markets in Asia, Africa, and beyond, offering competitive pricing and less stringent political conditions, its approach has also attracted criticism. Concerns over the quality of its products, the destabilizing effects of unregulated arms sales, and its willingness to engage with controversial regimes pose significant challenges to its image as a responsible global actor. Moreover, the arms trade has become a double-edged sword, providing economic and strategic benefits while exposing Beijing to risks of entanglement in conflicts and diplomatic backlash.

Looking forward, China's emphasis on integrating cutting-edge technologies such as AI, cybersecurity, and space capabilities into its military exports suggests that its influence in the arms trade will only grow. Yet, as global tensions rise, Beijing must navigate the delicate balance between advancing its geopolitical objectives and adhering to international norms, lest it faces isolation or intensified competition from established players.

In essence, China's arms export strategy is emblematic of its broader global ambitions: to assert itself as a central player on the world stage. Whether it can sustain this trajectory while managing the inherent challenges will significantly shape the future of international relations, regional stability, and the global arms market.

Sources:

Tian, N., & Fei, S. (2020). China's arms exports: An emerging challenger. Merics. Retrieved from www.merics.org/en/report/chinas-arms-exports-emerging-challenger

Vestner, T. (2020). The new geopolitics of the arms trade treaty. Arms Control Association. Retrieved from www.armscontrol.org/act/2020-12/features/new-geopolitics-arms-trade-treaty

Gill, D., & B. Huang, C. (2009). China's expanding role in peacekeeping: Prospects and policy implications. SIPRI. Retrieved from www.sipri.org/publications/2009/china-expanding-role-peacekeeping-prospects-and-policy-implications

Béraud-Sudreau, L., Liang, X., Wezeman, S. T., & Sun, M. (2022). Arms-production capabilities in the Indo-Pacific region: Measuring self-reliance. SIPRI. Retrieved from www.sipri.org/publications/2022/arms-production-capabilities-indo-pacific-region-measuring-self-reliance

Ghiasy, R., Su, F., & Saalman, L. (2018). The 21st century maritime silk road: Security implications and ways forward for the European Union. SIPRI. Retrieved from www.sipri.org/publications/2018/21st-century-maritime-silk-road-security-implications-and-ways-forward-european-union

Saalman, L. (2017). Factoring Russia into the US–Chinese equation on hypersonic glide vehicles. SIPRI. Retrieved from www.sipri.org/publications/2017/factoring-russia-us-chinese-equation-hypersonic-glide-vehicles

Anthony, I., Zhou, J., & Su, F. (2020). EU security perspectives in an era of connectivity: Implications for relations with China. SIPRI. Retrieved from www.sipri.org/publications/2020/eu-security-perspectives-era-connectivity-implications-relations-china

Yuan, J., Su, F., & Ouyang, X. (2022). China's evolving approach to foreign aid. SIPRI. Retrieved from www.sipri.org/publications/2022/chinas-evolving-approach-foreign-aid

Liff, A. P., & Erickson, A. S. (2013). Demystifying China's defence spending: Less mysterious in the aggregate. The China Quarterly, 216, 805-830. Retrieved from www.cambridge.org/core/journals/china-quarterly/article/demystifying-chinas-defence-spending-less-mysterious-in-the-aggregate/C12B97476AE05B750568F0F8A7B8B108

Kania, E.B., & Costello, J.K. (2018). The strategic support force and the future of chinese information operations. The Jamestown Foundation. Retrieved from jamestown.org/program/the-strategic-support-force-and-the-future-of-chinese-information-operations/

Bromley, M. (2012). China's arms transfers: An analysis of the 2010s. SIPRI. Retrieved from www.sipri.org/publications/2012/chinas-arms-transfers-analysis-2010s

Raska, M. (2019). The rise of China's defense industry: An analysis of its military modernisation. RSIS. Retrieved from www.rsis.edu.sg/rsis-publication/rsis/the-rise-of-chinas-defense-industry-an-analysis-of-its-military-modernization/#.Y81X6C-B1PY

Tian, N., & Fei, S. (2020). China's arms exports: An emerging challenger. Merics. Retrieved from www.merics.org/en/report/chinas-arms-exports-emerging-challenger

Gill, B., & Kim, M. (1995). China's arms acquisitions from abroad: A quest for 'superb and secret weapons'. Stockholm International Peace Research Institute. Retrieved from www.sipri.org/publications/1995/chinas-arms-acquisitions-abroad-quest-superb-and-secret-weapons

Blasko, D. J. (2020). The Chinese military speaks to itself, revealing doubts. War on the Rocks. Retrieved from warontherocks.com/2020/04/the-chinese-military-speaks-to-itself-revealing-doubts/

Kang, D. C. (2010). East Asia before the West: Five centuries of trade and tribute. Columbia University Press. Retrieved from cup.columbia.edu/book/east-asia-before-the-west/9780231153188

Gill, B., & Kim, M. (1995). China's arms acquisitions from abroad: A quest for 'superb and secret weapons'. Stockholm International Peace Research Institute. Retrieved from www.sipri.org/publications/1995/chinas-arms-acquisitions-abroad-quest-superb-and-secret-weapons

Raska, M. (2019). The rise of China's defense industry: An analysis of its military modernisation. RSIS. Retrieved from www.rsis.edu.sg/rsis-publication/rsis/the-rise-of-chinas-defense-industry-an-analysis-of-its-military-modernization/#.Y81X6C-B1PY

Tian, N., & Fei, S. (2020). China's arms exports: An emerging challenger. Merics. Retrieved from www.merics.org/en/report/chinas-arms-exports-emerging-challenger

Liff, A. P., & Erickson, A. S. (2013). Demystifying China's defence spending: Less mysterious in the aggregate. The China Quarterly, 216, 805-830. Retrieved from www.cambridge.org/core/journals/china-quarterly/article/demystifying-chinas-defence-spending-less-mysterious-in-the-aggregate/C12B97476AE05B750568F0F8A7B8B108

Kania, E.B., & Costello, J.K. (2018). The strategic support force and the future of Chinese information operations. The Jamestown Foundation. Retrieved from jamestown.org/program/the-strategic-support-force-and-the-future-of-chinese-information-operations/

Scobell, A., & Saunders, P. C. (2011). The PLA's role in China's foreign policy and security strategy. Strategic Studies Institute, U.S. Army War College. Retrieved from www.strategicstudiesinstitute.army.mil/pdffiles/PUB1040.pdf

Blasko, D. J. (2020). The Chinese military speaks to itself, revealing doubts. War on the Rocks. Retrieved from warontherocks.com/2020/04/the-chinese-military-speaks-to-itself-revealing-doubts/

Bromley, M. (2012). China's arms transfers: An analysis of the 2010s. SIPRI. Retrieved from www.sipri.org/publications/2012/chinas-arms-transfers-analysis-2010s

Gill, B., & Kim, M. (1995). China's arms acquisitions from abroad: A quest for 'superb and secret weapons'. Stockholm International Peace Research Institute. Retrieved from www.sipri.org/publications/1995/chinas-arms-acquisitions-abroad-quest-superb-and-secret-weapons

Raska, M. (2019). The rise of China's defense industry: An analysis of its military modernisation. RSIS. Retrieved from www.rsis.edu.sg/rsis-publication/rsis/the-rise-of-chinas-defense-industry-an-analysis-of-its-military-modernization/#.Y81X6C-B1PY

Tian, N., & Fei, S. (2020). China's arms exports: An emerging challenger. Merics. Retrieved from www.merics.org/en/report/chinas-arms-exports-emerging-challenger

Blasko, D. J. (2020). The Chinese military speaks to itself, revealing doubts. War on the Rocks. Retrieved from warontherocks.com/2020/04/the-chinese-military-speaks-to-itself-revealing-doubts/

Bromley, M. (2012). China's arms transfers: An analysis of the 2010s. SIPRI. Retrieved from www.sipri.org/publications/2012/chinas-arms-transfers-analysis-2010s

Kania, E.B., & Costello, J.K. (2018). The strategic support force and the future of Chinese information operations. The Jamestown Foundation. Retrieved from jamestown.org/program/the-strategic-support-force-and-the-future-of-chinese-information-operations/

Holmes, J. R. (2018). China's military sales in Africa: A strategic assessment. War on the Rocks. Retrieved from warontherocks.com/2018/04/chinas-military-sales-in-africa-a-strategic-assessment/

Anthony, I., & Wezeman, S. T. (2016). Arms production and military services: The emerging role of private companies. SIPRI. Retrieved from www.sipri.org/publications/2016/arms-production-and-military-services-emerging-role-private-companies