Climate Migration, Human Trafficking and National Security: Balancing Borders and Humanity

Forced by Nature, Exploited by Greed: Unraveling Climate Migration and Trafficking

TL;DR:

Climate Migration and Human Trafficking: Climate change is driving mass displacement through rising sea levels, extreme weather, and desertification, creating vulnerabilities exploited by traffickers. Displaced individuals often fall victim to forced labor, sexual exploitation, and modern slavery. Key regions like Central America, the Sahel, and the Sundarbans illustrate the intersection of environmental degradation, migration, and exploitation.

Geopolitical Dimensions: Climate migration reshapes borders and pressures national policies. Restrictive measures such as excessive border controls exacerbate risks by pushing migrants into dangerous smuggling networks. But countries cannot be blamed for trying to protect their national security and cultural interests. International legal frameworks fail to adequately protect climate-displaced individuals, highlighting global power imbalances and the lack of cohesive strategies.

Organized Crime and Exploitation: Criminal networks like the Sinaloa Cartel, 'Ndrangheta, and Yakuza profit from trafficking climate migrants, charging exorbitant fees and coercing victims into labor or sex work. Global estimates link climate migration with increased trafficking, showing a troubling correlation between environmental and human vulnerabilities.

Policy Gaps: Current frameworks lack recognition of climate migrants as protected categories, leaving them without legal status or safeguards. Limited resources for climate resilience and anti-trafficking measures, combined with political resistance to open migration pathways, allow exploitation to thrive.

Conclusion: Climate migration and human trafficking are deeply intertwined, demanding integrated global solutions. By addressing root causes and fostering international cooperation, nations can mitigate exploitation while upholding human rights and resilience in the face of climate change.

And now for the Deep Dive…

Introduction

The convergence of climate migration and human trafficking represents a profound global challenge, one rooted in the intersections of environmental, humanitarian, and geopolitical crises. Climate migration, driven by the devastating impacts of climate change—rising sea levels, extreme weather events, and desertification—forces millions to seek safety and livelihoods beyond their homes. These displaced populations, often desperate and vulnerable, become prime targets for human traffickers who exploit their precarious circumstances for profit through forced labor, sexual exploitation, and other forms of modern slavery. You cannot look at climate migration and human trafficking as separate and distinct issues. They are intertwined.

The geopolitical dimensions of this issue are vast and multifaceted. Climate migration reshapes borders, exacerbates international tensions, and pressures governments to adapt policies on immigration, national security, and resource allocation. Simultaneously, the prevalence of human trafficking as a byproduct of these forced migrations reveals gaps in international legal frameworks, insufficient protections for climate migrants, and the exploitation of chaotic migration flows by criminal networks.

This text delves into the intricate relationship between climate migration and human trafficking, exploring their root causes, key case studies, and the inadequacies of existing policies. By analyzing the socio-political impacts of these crises on nations and the individuals affected, this discussion highlights the urgent need for comprehensive international strategies that address both the root causes and humanitarian consequences of these intertwined phenomena.

Discussion

Climate migration refers to the movement of populations due to environmental changes, particularly those induced by climate change such as rising sea levels, increasing temperatures, and more frequent extreme weather events. This migration is often forced and can involve both internal displacement within a country or cross-border movements seeking safer or more livable conditions. Human trafficking, on the other hand, involves the exploitation of individuals through various means such as forced labor, sexual exploitation, or the sale of organs, often taking advantage of the vulnerability of migrants. While climate migration is primarily driven by environmental factors, human trafficking leverages these movements to exploit individuals for profit. This contrasts with migration motivated by economic opportunities, where individuals might move voluntarily in search of better job prospects, or migration driven by political or social reasons, such as fleeing persecution or seeking greater freedoms. The key difference lies in the element of choice; climate migrants and victims of human trafficking often have little to no choice in their decision to move, driven by survival instincts rather than aspirational goals.

The intersection of climate migration and human trafficking has significant global implications, creating a complex scenario where legal, ethical, and humanitarian considerations overlap. Climate change does not recognize national borders, and its impacts can destabilize regions, leading to increased migration flows. These flows are then exploited by traffickers who prey on the desperation of those displaced, offering deceptive promises of safety or employment. This nexus not only amplifies the scale of human trafficking but also complicates the categorization of migration types. Migrants fleeing climate-induced disasters might inadvertently enter into situations of trafficking, where they are manipulated by criminal networks looking to exploit the chaotic conditions post-disaster. This situation challenges international policy and legal frameworks, which often lack clear mechanisms to protect climate migrants from becoming victims of trafficking, thus blurring the lines between different migration motivations and outcomes.

Thesis

The thesis here is that climate change significantly exacerbates human trafficking by increasing forced migration. As climate disasters displace people from their homes, they become more vulnerable to exploitation. The urgency to relocate, often under dire circumstances, can lead individuals into the hands of traffickers who exploit this vulnerability. This scenario not only increases the incidence of human trafficking but also muddles the understanding and classification of migration types. Governments, NGOs, and international bodies must recognize this connection to develop more robust policies that address both climate resilience and anti-trafficking measures simultaneously. Without such integrated approaches, the distinction between voluntary economic migration, political asylum-seeking, and forced climate migration will continue to be obscured, potentially leading to inadequate responses to both environmental crises and human rights abuses. This linkage demands a nuanced understanding of migration dynamics in the context of a changing climate, urging a reevaluation of how we approach global migration policies to ensure they are inclusive, protective, and capable of addressing the intertwined challenges of climate change and human trafficking.

Climate Change as a Catalyst for Migration

Climate change is increasingly recognized as a significant catalyst for human migration, primarily through the intensification of natural disasters such as floods, droughts, and cyclones. These events, once considered anomalies, are becoming more frequent and severe due to global warming, altering landscapes and making traditional living areas untenable. Floods, for instance, can devastate agricultural lands, destroy homes, and contaminate water sources, leaving communities with little choice but to relocate. Droughts, on the other hand, lead to water scarcity and crop failures, pushing people from rural areas to urban centers or to different regions altogether. Cyclones, with their increased intensity, bring about immediate displacement and long-term economic ruin, especially in low-lying coastal areas, where recovery can be slow and resources scarce.

One vivid case study that illustrates the impact of climate-induced migration is in the Sundarbans, a vast mangrove forest shared by Bangladesh and India. Here, the combination of rising sea levels, increased salinity from seawater intrusion, and more frequent cyclonic storms has led to significant environmental degradation. This has not only affected the biodiversity but also the livelihoods of millions who depend on the forest's resources. Fishermen and farmers are finding their traditional practices unsustainable as salt water kills crops and fish stocks dwindle. Many are forced to migrate to cities like Dhaka or Kolkata, where they often end up in slums, facing new challenges like unemployment and social exclusion.

Another prominent example of climate-driven migration can be observed in Central America, particularly in countries like Guatemala, Honduras, and El Salvador. These regions have been hit hard by prolonged droughts, often intensified by climate change, leading to what is known as the "Dry Corridor." Here, the lack of rain has led to repeated crop failures, food insecurity, and economic hardship. As a result, many families are compelled to abandon their rural homes for urban areas within their own countries or migrate northward toward the United States in search of better living conditions. This migration is not just a matter of economic survival but also of escaping the increasingly harsh environmental conditions that are exacerbated by climate change.

A third example is seen in the Sahel region of Africa, where desertification, driven by climate change, is expanding the Sahara Desert southward. This creeping desertification has dramatically reduced arable land, forcing pastoralists and farmers to migrate either southwards or into urban centers. The competition for shrinking resources like water and pasture has led to conflicts and further displacement. In places like Burkina Faso, Mali, and Niger, the combination of climate change and socio-political instability has created a complex scenario where environmental factors significantly contribute to the choice to migrate, either internally or across borders.

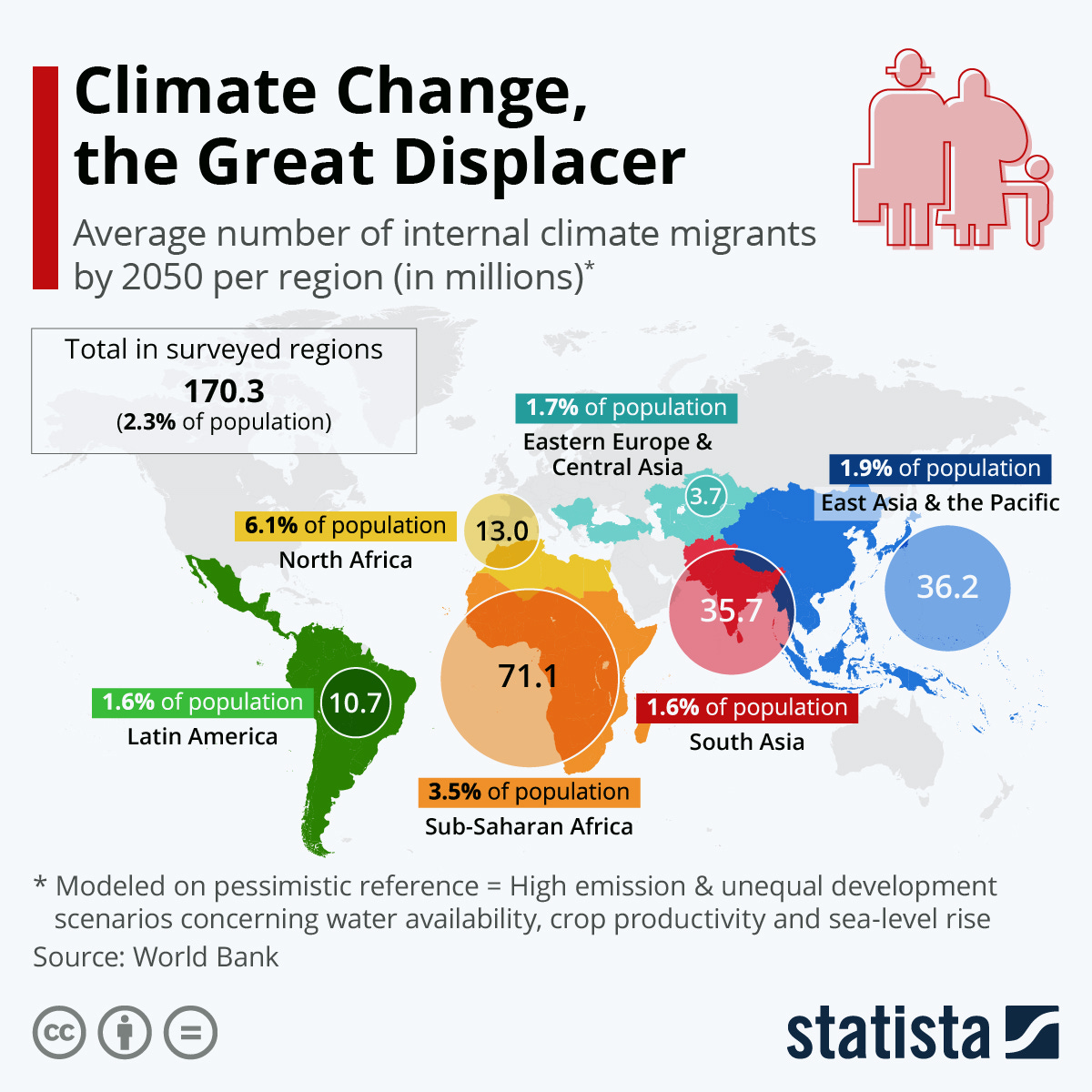

The global scale of this issue is underscored by various estimates from international organizations. The World Bank, in its "Groundswell" report, estimates that without significant climate action, there could be as many as 143 million internal climate migrants in Sub-Saharan Africa, South Asia, and Latin America by 2050. This staggering number reflects the potential for climate change to displace populations within national borders as conditions become inhospitable. The implications of such internal migration are profound, affecting not just the migrants but also the areas they move to, which might not have the infrastructure or resources to support sudden population increases.

This displacement often results in urban areas becoming overcrowded, straining resources like water, sanitation, and housing. The rapid urbanization can lead to the expansion of informal settlements, where living conditions are poor, and access to basic services is limited. This scenario is particularly evident in megacities of less developed countries, where climate migrants add to already burgeoning populations.

Moreover, the movement of large numbers of people due to environmental changes can lead to social tensions in receiving areas. When migrants from rural or different climatic zones arrive in new regions, they often bring with them different cultural practices, languages, and needs, which can cause friction with local populations unless managed with inclusive policies and community integration strategies.

The implications for international policy are vast. There is a growing recognition that climate change needs to be considered in migration policies. Countries must adapt not only their environmental policies but also immigration and urban planning to accommodate climate migrants. This might involve creating legal pathways for climate-displaced individuals, similar to those for refugees, or investing in resilience-building programs in vulnerable regions to mitigate the need for migration.

The narrative around climate migration is also shifting from seeing it solely as a crisis to recognizing it as a potential adaptation strategy. If managed well, migration can be part of a broader strategy to adapt to climate change, allowing people to move to safer, more sustainable areas where they can continue to contribute to society and economy. However, this requires a coordinated international response, with developed countries, which have historically contributed more to climate change, playing a significant role in supporting adaptation efforts in more vulnerable regions.

In essence, as climate change continues to reshape our planet, it will undoubtedly continue to act as a catalyst for migration. Understanding and addressing this through case studies like the Sundarbans, Central America, and the Sahel provides critical insights into the human cost of climate change. It's imperative that global policies evolve to not only mitigate climate change but also to manage its human consequences, ensuring that migration, when it occurs, does not lead to further vulnerability but rather to opportunities for adaptation and resilience.

The Link Between Migration and Human Trafficking

The vulnerability of climate-displaced populations is a critical factor in the nexus between migration and human trafficking. When environmental changes force people from their homes, they often leave behind not only their physical belongings but also their social networks, support systems, and legal protections. This displacement can occur suddenly, as in the case of a devastating flood or hurricane, or gradually, like the slow salinization of agricultural lands, pushing people into situations where they are desperate for survival. These migrants, particularly those crossing borders without legal documentation, find themselves in precarious positions where they can be easily exploited. The promise of a safe haven or employment is a common lure used by traffickers, preying on the migrants' desperation and hope for a better life.

The mechanisms of exploitation that climate migrants face are varied but include forced labor, sexual exploitation, and modern slavery. In regions where climate migrants arrive, often without legal status or the local knowledge to navigate their new environments, they can be coerced into exploitative work arrangements. For example, forced labor might involve agricultural work where migrants are indebted to employers for their passage or initial living expenses, a practice known as debt bondage. Sexual exploitation is another grim reality, where women and children, in particular, might be manipulated into prostitution under the guise of marriage or job opportunities. Modern slavery encompasses these and other practices where individuals are controlled for economic gain, their freedom and rights stripped away, often under the threat of violence or through deceit.

Empirical evidence from organizations like the International Institute for Environment and Development (IIED) and Anti-Slavery International has illuminated this connection. IIED's research highlights how environmental degradation in places like the Mekong Delta in Vietnam or the drought-stricken regions of Africa leads to migration, which in turn increases vulnerability to trafficking. Anti-Slavery International has documented cases where climate change-induced migration in Bangladesh leads to trafficking, with migrants ending up in exploitative work conditions in India or further afield. These studies underscore that as climate change displaces more people, the opportunities for human trafficking grow, making the issue not just a human rights concern but also a climate justice issue.

International organized crime groups play a significant role in human trafficking, often exploiting the chaos of mass migrations for profit. One notorious group is the 'Ndrangheta, an Italian mafia syndicate known for its involvement in human trafficking among other crimes. They have operations that extend beyond Italy, including routes to the United States, where they traffic individuals from Eastern Europe and Africa, often under the guise of providing legitimate employment. Statistics from Europol suggest that the 'Ndrangheta is responsible for trafficking thousands of individuals yearly, with a significant portion ending up in forced labor or sex work.

Another group, the Sinaloa Cartel from Mexico, also engages in human trafficking, particularly to the US. Though primarily known for drug trafficking, they have diversified into human smuggling and exploitation, with estimates suggesting they traffic hundreds of thousands of people across the US border annually, many of whom fall into situations of exploitation once they cross. The Sinaloa Cartel, one of the most powerful drug trafficking organizations in the world, has expanded its criminal portfolio to include human trafficking, leveraging the chaos and desperation of migration, particularly along the US-Mexico border. The cartel profits from this illicit activity by controlling smuggling routes, charging migrants exorbitant fees for passage, and exploiting them once they are in transit or after they cross the border. Reports from various sources, including posts on social media, indicate that the Sinaloa Cartel can charge up to $40,000 per person to smuggle individuals from Venezuela to the United States, highlighting the lucrative nature of this operation. This fee is part of a broader system where migrants pay for each segment of their journey, often accumulating debt that can lead to forced labor or sexual exploitation to settle what they owe.

The cartel's involvement in human trafficking is not limited to mere transportation. They employ a sophisticated network of "coyotes" or human smugglers, who are often part of or closely aligned with the cartel. These smugglers collect payments from migrants, sometimes in advance, which can range from several thousand to tens of thousands of dollars based on the distance and risk involved in the journey. The Sinaloa Cartel has been known to use violence or the threat thereof to ensure compliance and payment. In some cases, if migrants cannot pay, they might be subjected to exploitation, including forced labor in agriculture, domestic work, or even the drug trade itself, or they might be sold into sex trafficking networks. A former Acting Commissioner of Customs and Border Protection, Mark Morgan, stated that the Sinaloa Cartel's annual profit from human trafficking has escalated from an estimated $500 million to $13 billion, illustrating the scale and profitability of their operations.

Moreover, the Sinaloa Cartel's human trafficking operations are not just about moving people across borders. They also involve the exploitation of migrants once they reach their destinations. For example, once in the United States, migrants might be coerced into working off their smuggling debts through various forms of labor exploitation. The cartels often control these labor markets, particularly in sectors like construction, agriculture, and hospitality, where undocumented workers are less likely to report abuses due to their legal status. This exploitation can extend to sexual servitude, where women and children are particularly vulnerable, being trafficked into prostitution or other forms of sexual exploitation. The exact numbers of victims are hard to quantify due to the clandestine nature of these activities, but the scale can be inferred from the cartel's overall revenue and the known number of migrants crossing the border each year.

The operations of the Sinaloa Cartel in human trafficking also have a significant impact on local communities and law enforcement. They often employ aggressive tactics to maintain control over smuggling corridors, which can include extortion, kidnapping, and murder. In areas like the Tohono O'odham reservation, where there was a significant operation in 2011 leading to the arrest of 27 members for both drug and human smuggling, it's clear that the cartel's influence extends into indigenous lands, complicating local and federal responses. The presence of the cartel not only increases crime rates but also fosters an environment where human rights abuses go unchecked, as the focus on profit maximization often overrides any concern for the welfare of the migrants they traffic. This complex web of criminal activity underscores the need for a coordinated, international effort to dismantle such networks and protect vulnerable populations from exploitation.

In Southeast Asia, the Yakuza in Japan has been linked to human trafficking, particularly for sexual exploitation. They often use deceptive job offers to lure victims from poorer neighboring countries like the Philippines or Thailand, with statistics indicating that thousands are trafficked into Japan each year. In Eastern Europe, the Bratva or Russian mafia has a notorious reputation for trafficking, with operations spreading across Europe and into North America, exploiting the vulnerability of migrants from former Soviet states.

The empirical data further confirms this grim reality. A report by the International Labour Organization (ILO) estimates that 24.9 million people worldwide are victims of forced labor, with a significant number being migrants or refugees. The Walk Free Foundation's Global Slavery Index provides detailed statistics on the prevalence of modern slavery, showing that countries with significant climate vulnerability often correlate with higher instances of human trafficking. This connection is not coincidental; it's a direct result of increased migration due to environmental pressures.

Moreover, the UNODC's Global Report on Trafficking in Persons notes that conflict, poverty, and environmental disasters are key drivers of human trafficking. They record a notable increase in trafficking in areas directly affected by climate change, with the Middle East and North Africa showing a sharp rise in trafficking cases linked to climate-induced migration.

The complexity of this issue is exacerbated by the global nature of organized crime. Human trafficking routes are often international, with victims being moved from one country to another, sometimes continents away, making it a transnational crime requiring international cooperation to combat. The involvement of these crime groups in human trafficking is not just about exploitation but also about controlling migration routes, which becomes more profitable and less risky during times of large-scale displacement caused by climate change.

In addressing this link, there is a need for policies that not only focus on stopping human trafficking but also on mitigating the root causes of climate migration. This includes international efforts to reduce carbon emissions, support climate adaptation in vulnerable regions, and provide legal pathways for migration that do not leave individuals at the mercy of traffickers.

Furthermore, there must be an enhancement in international law enforcement cooperation to dismantle these criminal networks. Programs aimed at educating potential migrants about the risks of trafficking, coupled with safe migration corridors and better border management, could reduce the opportunities for exploitation.

The narratives from survivors and the work of NGOs paint a vivid picture of the human cost of this nexus. Stories from regions like the Horn of Africa, where drought drives migration, or from the Caribbean after devastating hurricanes, show individuals who, in search of safety or a new beginning, end up in the hands of traffickers.

In sum, the link between migration and human trafficking, especially in the context of climate change, is undeniable and growing. It demands a multifaceted response that includes immediate action against trafficking, long-term environmental strategies, and a compassionate understanding of why people are forced to move in the first place. Without addressing climate change, we will continue to see an increase in human vulnerability to exploitation, perpetuating a cycle of suffering that spans from the environmental to the human rights domain.

Geopolitical Dimensions

The geopolitical dimensions of climate migration are complex, particularly in how nations respond to the influx of climate migrants through their national policies and border controls. Many countries have implemented restrictive policies aimed at managing or reducing migration flows, often driven by concerns over national security, economic resources, or political popularity. For example, in Europe, the response to the Syrian refugee crisis, influenced by climate-related instability, has led to tightened border controls and the erection of physical barriers in countries like Hungary and Greece. In the United States, policies have fluctuated but often include measures like the "Remain in Mexico" policy, which forces asylum seekers to wait in Mexico, potentially exposing them to further risks, including trafficking. These policies not only restrict legal migration pathways but can inadvertently increase the vulnerability of migrants to trafficking by pushing them into the hands of smugglers or exploitative networks.

On the international stage, there's a noticeable gap in legal frameworks specifically designed to protect climate migrants from human trafficking. The 1951 Refugee Convention and its 1967 Protocol define refugees in terms of persecution rather than environmental displacement, leaving climate migrants in a legal grey area. Efforts like the Nansen Initiative and its successor, the Platform on Disaster Displacement, aim to address this by developing guidelines for protection, but these are non-binding. The lack of a comprehensive international legal framework means that current human rights and anti-trafficking laws, while applicable, do not explicitly cover the unique circumstances of climate-displaced individuals. This legal vacuum complicates the protection of these migrants, as they might not qualify for the same international protections afforded to those fleeing war or persecution, thus heightening their risk of exploitation.

The power dynamics between developed and developing nations further complicate the geopolitical landscape concerning climate migration. Developed nations, historically the largest contributors to greenhouse gas emissions, bear significant responsibility for the climate changes that drive migration. Yet, their policies on migration often do not reflect this responsibility. For instance, while countries like the United States, Canada, and those in the European Union advocate for climate action, their immigration policies can be stringent, sometimes even increasing border militarization rather than creating accessible pathways for climate migrants. This discrepancy can be seen in the reluctance to ratify agreements like the Global Compact for Safe, Orderly, and Regular Migration, which aims to manage migration humanely but has faced opposition from some developed nations.

Moreover, the financial commitments from developed to developing countries for climate mitigation and adaptation, such as the $100 billion per year promised by developed nations under the Paris Agreement, have been inconsistently met. This lack of support exacerbates the conditions that force migration in the first place, creating a cycle where developed nations contribute to problems they are also resistant to addressing through open migration policies. This dynamic not only reflects a form of climate injustice but also sets the stage for increased instances of human trafficking as desperate migrants seek entry into countries with better conditions, often through illegal or exploitative means.

In addition, the geopolitical responses to climate migration can lead to a reshaping of international relations. Countries receiving large numbers of migrants might seek to influence or pressure countries of origin to manage migration at the source, sometimes through aid or development projects that focus more on containment than on solving underlying issues like climate resilience. This can create tension or cooperation depending on how these policies are perceived, with some seeing them as neocolonial or others as necessary international aid.

The absence of robust international cooperation in managing climate migration not only affects the migrants but also undermines global efforts to combat human trafficking. Without cooperative frameworks, the burden falls unevenly on transit and destination countries, which might not have the resources or legal structures to handle the influx humanely. This scenario can lead to policies that prioritize security over human rights, further endangering migrants.

In sum, the geopolitical dimensions of climate migration and human trafficking reveal a world where national interests often overshadow global responsibilities. The interplay between restrictive migration policies, inadequate international legal protections, and the power imbalance in global climate action creates a fertile ground for human trafficking. Addressing these issues requires not only a reevaluation of how we view migration in the context of climate change but also a commitment to international cooperation that recognizes the shared responsibility in both causing and mitigating the effects of climate displacement.

Case Studies in Geopolitics

The geopolitical dimensions of climate migration are complex, particularly in how nations respond to the influx of climate migrants through their national policies and border controls. Many countries have implemented restrictive policies aimed at managing or reducing migration flows, often driven by concerns over national security, economic resources, or political popularity. For example, in Europe, the response to the Syrian refugee crisis, influenced by climate-related instability, has led to tightened border controls and the erection of physical barriers in countries like Hungary and Greece. In the United States, policies have fluctuated but often include measures like the "Remain in Mexico" policy, which forces asylum seekers to wait in Mexico. These policies not only restrict legal migration pathways but can inadvertently increase the vulnerability of migrants to trafficking by pushing them into the hands of smugglers or exploitative networks.

On the international stage, there is a noticeable gap in legal frameworks specifically designed to protect climate migrants from human trafficking. The 1951 Refugee Convention and its 1967 Protocol define refugees in terms of persecution rather than environmental displacement, leaving climate migrants in a legal grey area. Efforts like the Nansen Initiative and its successor, the Platform on Disaster Displacement, aim to address this by developing guidelines for protection, but these are non-binding. The lack of a comprehensive international legal framework means that current human rights and anti-trafficking laws, while applicable, do not explicitly cover the unique circumstances of climate-displaced individuals. This legal vacuum complicates the protection of these migrants, as they might not qualify for the same international protections afforded to those fleeing war or persecution, thus heightening their risk of exploitation.

The power dynamics between developed and developing nations further complicate the geopolitical landscape concerning climate migration. Developed nations, historically the largest contributors to greenhouse gas emissions, policies on migration often do not reflect this reality of source. For instance, while countries like the United States, Canada, and those in the European Union advocate for climate action, their immigration policies can be stringent, sometimes even increasing border militarization rather than creating accessible pathways for climate migrants. This discrepancy can be seen in the reluctance to ratify agreements like the Global Compact for Safe, Orderly, and Regular Migration, which aims to manage migration humanely but has faced opposition from some developed nations.

Moreover, the financial commitments from developed to developing countries for climate mitigation and adaptation, such as the $100 billion per year promised by developed nations under the Paris Agreement, have been inconsistently met. This lack of support exacerbates the conditions that force migration in the first place, creating a cycle where developed nations contribute to problems they are also resistant to addressing through open migration policies. This dynamic not only reflects a form of climate injustice but also sets the stage for increased instances of human trafficking as desperate migrants seek entry into countries with better conditions, often through illegal or exploitative means.

In addition, the geopolitical responses to climate migration can lead to a reshaping of international relations. Countries receiving large numbers of migrants might seek to influence or pressure countries of origin to manage migration at the source, sometimes through aid or development projects that focus more on containment than on solving underlying issues like climate resilience. This can create tension or cooperation depending on how these policies are perceived, with some seeing them as neocolonial or others as necessary international aid.

The absence of robust international cooperation in managing climate migration not only affects the migrants but also undermines global efforts to combat human trafficking. Without cooperative frameworks, the burden falls unevenly on transit and destination countries, which might not have the resources or legal structures to handle the influx humanely. This scenario can lead to policies that prioritize security over human rights, further endangering migrants.

In essence, the geopolitical dimensions of climate migration and human trafficking reveal a world where national interests often overshadow global responsibilities. The interplay between restrictive migration policies, inadequate international legal protections, and the power imbalance in global climate action creates a fertile ground for human trafficking. Addressing these issues requires not only a reevaluation of how we view migration in the context of climate change but also a commitment to international cooperation that recognizes the shared responsibility in both causing and mitigating the effects of climate displacement.

Case Studies

In Asia, Bangladesh serves as a poignant case study where climate change and human trafficking intersect. The country is particularly vulnerable to sea-level rise and cyclones, which have led to significant internal displacement, especially in low-lying areas like the coastal regions. The government has responded by constructing shelters and promoting climate-resilient infrastructure, but these measures have limitations. Human trafficking has increased, particularly after disasters like Cyclone Sidr in 2007 and Cyclone Amphan in 2020, where traffickers exploited the chaos to lure vulnerable individuals with false promises of work. Bangladesh has attempted to combat trafficking through legal frameworks like the Human Trafficking Deterrence and Suppression Act 2012, yet enforcement remains weak, and corruption can undermine these efforts. The lack of comprehensive policies that address both climate migration and trafficking leaves a gap where exploitation thrives.

Moving to Europe, Greece has experienced significant challenges with both climate migration and human trafficking, especially in the context of the broader European migrant crisis. Climate change exacerbates migration from regions like the Middle East and North Africa, where drought and conflict, often tied to environmental degradation, drive people towards Europe. Greece, as a primary entry point, has seen an influx of migrants arriving by sea, leading to a complex situation where human trafficking networks exploit these routes. The country has implemented the National Referral Mechanism for the protection of trafficking victims, yet the focus is often more on border control than on the underlying causes of migration or the protection of migrants from trafficking. The EU's broader approach, through policies like the Dublin Regulation, places disproportionate responsibility on border countries like Greece, which sometimes inadvertently aids traffickers by creating a system where migrants are stuck in limbo, vulnerable to exploitation.

In North America, the United States faces a dual challenge with climate-induced migration from within its borders and from Latin America. Within the U.S., states like Louisiana and Florida are dealing with climate migrants from coastal areas affected by hurricanes and sea-level rise. However, there is a notable absence of federal policies explicitly addressing internal climate migration, leaving local governments to manage the fallout, including potential increases in human trafficking due to economic desperation. For international migration, especially from Central America where climate change exacerbates conditions like drought in the Dry Corridor, the U.S. has oscillated between policies that could either protect or endanger migrants. The Trump administration's policies like family separation and "Remain in Mexico" increased vulnerability to trafficking by leaving migrants in dangerous conditions. Conversely, the Biden administration has attempted to address trafficking through the Trafficking Victims Protection Reauthorization Act, was a failure. Where the focus should settle either on border security or humanitarian aid or legal migration pathways for climate refugees remains a point of contention.

In each of these contexts, the response to climate migration and human trafficking varies but shares common themes. In Asia, the challenge is often compounded by limited resources and governance issues, leading to reactive rather than preventive measures. In Europe, there is a tension between humanitarian responses and the political desire to control migration, which can inadvertently support trafficking networks. In North America, particularly in the U.S., there is a struggle between immigration policies that might protect or exploit migrants, with the latter often prevailing due to political pressures around border security.

There is no clear answer simple answer to this. To deny that there is climate change is foolish. To deny that there will be climate change is foolish. To deny that there will be exploitation in the form of human trafficking when these conditions exist is also foolish. A country cannot simply throw open its borders, but also there is the humanity of it all with profound cultural and national security issues that rightly get put to the forefront.

Policy Responses and Gaps

International bodies like the United Nations (UN) and the International Organization for Migration (IOM) have been actively involved in addressing the intersection of climate migration and human trafficking through various initiatives. The UN, through its agencies like the UN Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), focuses on policy development, research, and capacity building to combat trafficking, with special attention to how climate change exacerbates these issues. The IOM, on the other hand, has programs aimed at both managing migration in a way that respects human rights and directly tackling human trafficking through its counter-trafficking efforts. This includes the Global Migration Data Portal, which provides data to inform policy, and direct assistance to victims of trafficking. Despite these efforts, the scale of the problem often outpaces the resources and implementation capabilities of these organizations.

The challenges in effectively addressing this nexus are multifaceted. Political will is often lacking, with many countries prioritizing border security over humanitarian concerns for obvious and understandable reasons, especially in the context of migration. Resource allocation for both climate adaptation and anti-trafficking measures is frequently inadequate, with funds not always reaching the areas where they are most needed. Legal frameworks, particularly at the international level, struggle to adapt to the nuances of climate-induced migration, leaving a gap where traffickers can operate with relative impunity. Additionally, there is a tension between national sovereignty and international obligations, where countries might resist policies that could be seen as infringing on their ability to control their borders, even when these policies are meant to protect human rights.

Recommendations for integrating anti-trafficking measures into climate policy include creating legal pathways for climate migrants that reduce their vulnerability to exploitation. This could involve recognizing climate displacement as a basis for protection similar to that given to refugees, thereby providing legal status and rights to those forced to move due to environmental changes. Enhanced international cooperation is crucial, not just for sharing intelligence on trafficking networks but also for funding and capacity-building in countries most affected by climate change. Policies should also focus on resilience, helping communities adapt in place where possible, reducing the need for migration. Moreover, there needs to be a concerted effort to educate potential migrants about the risks of trafficking and to empower local communities with the tools to recognize and report such crimes.

The incoming Trump administration, if it mirrors the policies of the previous term, might adopt stringent border control measures, which could significantly impact how climate migration and human trafficking are managed. Policies like constructing or expanding border walls, reducing legal migration pathways, and potentially withdrawing from international agreements could exacerbate the risks of trafficking. If other governments follow suit with similar controlled border policies, the global landscape for climate migrants could become even more challenging. Such policies might push migrants into more dangerous routes, directly into the arms of human traffickers who exploit these vulnerabilities. This is well within the President’s prerogatives and has support from Americans to what degree is debatable.

If destination countries essentially shut off, the consequences could be severe. Migrants would be forced into more perilous journeys, increasing the likelihood of exploitation. Without legal avenues for migration, the informal networks controlled by traffickers would become even more dominant, leading to a rise in human rights abuses. This scenario could lead to a humanitarian crisis in transit countries or regions where migrants accumulate, unable to move forward, thereby straining local resources and potentially leading to social unrest. The lack of legal migration options would also mean less oversight and protection for those on the move, making international anti-trafficking efforts even more complex.

In response to such a scenario, there would be a pressing need for alternative strategies. This might involve fostering regional agreements where countries share the responsibility for climate migrants, creating safe zones or corridors for migration within regions, and significantly increasing international aid for both climate adaptation and emergency response in source countries. NGOs and civil society would need to play a larger role in providing support where governments fail or are absent. Ultimately, without open and humane migration policies, the global community might see an increase in modern slavery, exploitation, and conflict as the pressures of climate change and population displacement intensify.

Conclusion

The intersection of climate migration and human trafficking presents an urgent and complex challenge that spans environmental, human rights, and geopolitical domains. Climate change continues to displace millions, driving them into circumstances of vulnerability that traffickers exploit for profit. This convergence not only highlights the human cost of environmental degradation but also underscores critical gaps in international legal protections and policy responses.

Addressing these interconnected crises demands a multifaceted approach. Governments and international organizations must prioritize creating legal pathways for climate migrants, strengthening anti-trafficking measures, and enhancing resilience in vulnerable communities to reduce forced displacement. Equally important is fostering international cooperation to dismantle trafficking networks and ensure equitable climate adaptation efforts, particularly in developing nations most affected by climate change.

Ultimately, tackling these challenges requires a shift in how migration and human trafficking are perceived—not as separate crises but as deeply intertwined phenomena. Acknowledging and addressing their root causes through integrated, compassionate, and forward-thinking policies will be critical to mitigating their impact and fostering a more equitable and humane global response to climate change and its cascading consequences.

Sources:

United Nations. (2019, July 23). Climate change 'a threat multiplier' for trafficking, UNODC chief says. UN News. https://news.un.org/en/story/2019/07/1043391

Parks, C. (2019, August 22). Climate change is fueling human trafficking. The Revelator. https://therevelator.org/climate-change-human-trafficking/

Soroptimist International. (n.d.). The effects of climate change on migration and human trafficking. Soroptimist International. https://www.soroptimistinternational.org/the-effects-of-climate-change-on-migration-and-human-trafficking/

International Institute for Environment and Development. (2014). Climate change, migration and human security: The nexus between policy, law and reality. IIED. https://www.iied.org/20936iied

Crawford, A. (2023, February 2). Dangers, modes, and climate change: Human trafficking. New Security Beat. https://www.newsecuritybeat.org/2023/02/dangers-modes-climate-change-human-trafficking/

International Institute for Environment and Development. (n.d.). Climate change, migration, vulnerability and trafficking. IIED. https://www.iied.org/climate-change-migration-vulnerability-trafficking

PreventionWeb. (n.d.). Report: Climate change, migration and vulnerability to trafficking. PreventionWeb. https://www.preventionweb.net/publication/report-climate-change-migration-and-vulnerability-trafficking

CAFOD. (n.d.). Climate change, migration and human trafficking. CAFOD. https://cafod.org.uk/about-us/policy-and-research/sustainable-development-goals/climate-change-migration-and-human-trafficking

Kaye, J. (2017). The nexus between climate change, displacement, and human trafficking in South Asia. Anti-Trafficking Review, (8), 1-19. https://antitraffickingreview.org/index.php/atrjournal/article/view/226/212

Human Rights Pulse. (n.d.). Climate change, displacement, and human trafficking. Human Rights Pulse. https://www.humanrightspulse.com/mastercontentblog/climate-change-displacement-and-human-trafficking

Taylor, L. (2021, September 20). Climate crisis leaving millions at risk of trafficking and slavery, experts warn. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2021/sep/20/climate-crisis-leaving-millions-at-risk-of-trafficking-and-slavery

The Energy Mix. (2021, September 28). Climate change leaves migrants vulnerable to slavery, human trafficking. The Energy Mix. https://www.theenergymix.com/2021/09/28/climate-change-leaves-migrants-vulnerable-to-slavery-human-trafficking/

ReliefWeb. (2019, September 23). Climate refugees are increasingly victims of exploitation. ReliefWeb. https://reliefweb.int/report/world/climate-refugees-are-increasingly-victims-exploitation

Saldinger, A. (2019, September 23). Fleeing home: Refugees and human trafficking. Council on Foreign Relations. https://www.cfr.org/blog/fleeing-home-refugees-and-human-trafficking

Human Trafficking Search. (n.d.). The climate is changing and so is human trafficking. Human Trafficking Search. https://humantraffickingsearch.org/the-climate-is-changing-and-so-is-human-trafficking/

Anti-Slavery International. (n.d.). Climate change. Anti-Slavery International. https://www.antislavery.org/what-we-do/climate-change/

International Organization for Migration. (n.d.). Human trafficking and climate mobility: Key takeaways from COP29. IOM. https://migrantprotection.iom.int/en/spotlight/articles/event/human-trafficking-and-climate-mobility-key-takeaways-cop29

Plant With Purpose. (n.d.). Connecting the dots: Human trafficking and climate change. Plant With Purpose. https://plantwithpurpose.org/connecting-the-dots-human-trafficking-and-climate-change/

Thomson Reuters Foundation. (2021, September 20). Climate crisis leaving millions at risk of trafficking and slavery: Experts. Thomson Reuters Foundation. https://news.trust.org/item/20210920190635-w90ub/

Kumar, C. (2015, February 18). Climate change and human trafficking: A deadly combination. The Diplomat. https://thediplomat.com/2015/02/climate-change-and-human-trafficking-a-deadly-combination/

UN Women. (n.d.). Climate change, migration and vulnerability to trafficking. UN Women. https://wrd.unwomen.org/practice/resources/climate-change-migration-and-vulnerability-trafficking

CarbonBrief. (n.d.). Climate migration. CarbonBrief. https://interactive.carbonbrief.org/climate-migration/index.html

Natural Resources Defense Council. (n.d.). Climate migration and equity. NRDC. https://www.nrdc.org/stories/climate-migration-equity

Ferris, E. (2020, September 24). The climate crisis, migration, and refugees. Brookings. https://www.brookings.edu/articles/the-climate-crisis-migration-and-refugees/

Zamudio, A. (2020, November 19). Climate migration 101: An explainer. Migration Policy Institute. https://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/climate-migration-101-explainer

Zarocostas, J. (2019, October 15). Climate change is already fueling global migration. The world isn't ready to meet people's needs, experts say. PBS NewsHour. https://www.pbs.org/newshour/world/climate-change-is-already-fueling-global-migration-the-world-isnt-ready-to-meet-peoples-needs-experts-say

Ferris, E. (2021, September 15). Climate migration: Deepening our solutions. Brookings. https://www.brookings.edu/articles/climate-migration-deepening-our-solutions/

Rees, M. (2021, October 26). Climate-fueled migration requires a different approach. New America. https://www.newamerica.org/planetary-politics/blog/climate-fueled-migration-requires-a-different-approach/

McAdam, J., & Ferris, E. (2016). Climate change and displacement: Multidisciplinary perspectives. PubMed Central. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4847105/

Taylor, L. (2022, August 18). Century of climate crisis migration: Why we need a plan for the great upheaval. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/news/2022/aug/18/century-climate-crisis-migration-why-we-need-plan-great-upheaval

Zickfeld, K. (2021, August 24). Climate change and trapped populations. Migration Policy Institute. https://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/climate-change-trapped-populations

NPR. (2024, March 26). How climate-driven migration could change the face of the U.S. NPR. https://www.npr.org/2024/03/26/1239904742/how-climate-driven-migration-could-change-the-face-of-the-u-s

Ferris, E., & Weerasinghe, S. (2019). The climate crisis, migration, and refugees. Brookings. https://www.brookings.edu/research/the-climate-crisis-migration-and-refugees/

United Nations. (2019, July 24). Climate change a threat multiplier for global peace, security, UN chief warns. UN News. https://news.un.org/en/story/2019/07/1043551

Vision of Humanity. (n.d.). Climate change-induced migration and conflict. Vision of Humanity. https://www.visionofhumanity.org/climate-change-induced-migration-conflict/

McLeman, R., & Smit, B. (2006). Migration as an adaptation to climate change. Climatic Change, 76(1-2), 31-53. https://migrationpolicy.org/article/climate-impacts-drivers-migration

International Organization for Migration. (n.d.). Environmental migration. IOM. https://environmentalmigration.iom.int/environmental-migration

The Organisation for World Peace. (n.d.). Climate change: A catalyst for mass migration. The OWP. https://theowp.org/reports/climate-change-a-catalyst-for-mass-migration/

International Organization for Migration. (2018, September 24). Migration as an adaptation strategy to climate change. IOM. https://weblog.iom.int/migration-adaptation-strategy-climate-change

Stanford University. (n.d.). How does climate change affect migration? Stanford Sustainability. https://sustainability.stanford.edu/news/how-does-climate-change-affect-migration

United Nations. (n.d.). Will there be climate migrants en masse? UN Chronicle. https://www.un.org/en/chronicle/article/will-there-be-climate-migrants-en-masse

House of Lords Library. (2021, October 28). Climate change-induced migration: UK collaboration with international partners. Lords Library. https://lordslibrary.parliament.uk/climate-change-induced-migration-uk-collaboration-with-international-partners/

Council on Foreign Relations. (2021, August 25). Climate change is fueling migration. Do climate migrants have legal protections? CFR. https://www.cfr.org/in-brief/climate-change-fueling-migration-do-climate-migrants-have-legal-protections

ProPublica. (2020, September 15). The great climate migration has begun. ProPublica. https://www.propublica.org/article/climate-change-will-force-a-new-american-migration

United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. (n.d.). Human trafficking and migrant smuggling. UNODC. https://www.unodc.org/e4j/en/secondary/human-trafficking-and-migrant-smuggling.html

UNHCR. (n.d.). Trafficking in persons. UNHCR. https://www.unhcr.org/what-we-do/protect-human-rights/asylum-and-migration/trafficking-persons

Migration Data Portal. (n.d.). Human trafficking. Migration Data Portal. https://www.migrationdataportal.org/themes/human-trafficking

INTERPOL. (n.d.). Human trafficking and migrant smuggling. INTERPOL. https://www.interpol.int/Crimes/Human-trafficking-and-migrant-smuggling

INTERPOL. (n.d.). Human trafficking and migrant smuggling. INTERPOL. https://www.interpol.int/en/Crimes/Human-trafficking-and-migrant-smuggling

ReliefWeb. (2021, October 11). Migrants and their vulnerability to human trafficking, modern slavery and forced labour. ReliefWeb. https://reliefweb.int/report/world/migrants-and-their-vulnerability-human-trafficking-modern-slavery-and-forced-labour

Global Sisters Report. (2021, November 10). Breaking the link between human trafficking and forced migration. Global Sisters Report. https://www.globalsistersreport.org/community/news/breaking-link-between-human-trafficking-and-forced-migration

Caritas Internationalis. (n.d.). Migration. Caritas. https://www.caritas.org/what-we-do/migration/

Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights. (2016, September). Human trafficking risks in the context of migration. OHCHR. https://www.ohchr.org/en/stories/2016/09/human-trafficking-risks-context-migration

Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights. (n.d.). Migration and human trafficking. OHCHR. https://www.ohchr.org/EN/NewsEvents/Pages/MigrationHumanTrafficking.aspx

PBS NewsHour. (2019, October 7). As global migration surges, trafficking has become a multi-billion dollar business. PBS. https://www.pbs.org/newshour/show/as-global-migration-surges-trafficking-has-become-a-multi-billion-dollar-business

Saldinger, A. (2019, September 23). Fleeing home: Refugees and human trafficking. Council on Foreign Relations. https://www.cfr.org/blog/fleeing-home-refugees-and-human-trafficking

Luttrell, T. (2021, April 28). Opinion: Human and drug trafficking fueled by cartels. Congressman Morgan Luttrell. https://luttrell.house.gov/media/in-the-news/opinion-human-and-drug-trafficking-fueled-cartels

NBC News. (2020, April 24). First drugs, then oil, now Mexican cartels turn to human trafficking. NBC News. https://www.nbcnews.com/news/latino/first-drugs-then-oil-now-mexican-cartels-turn-human-trafficking-n1195551

Newsweek. (2023, December 14). Fentanyl, human smuggling: Cartel gangs, sanctions, United States. Newsweek. https://www.newsweek.com/fentanyl-human-smuggling-cartel-gangs-sanctions-united-states-1958686

Al Jazeera. (2016, January 24). Deadly human trafficking business on Mexico-US border. Al Jazeera. https://www.aljazeera.com/features/2016/1/24/deadly-human-trafficking-business-on-mexico-us-border

Newsweek. (2019, May 15). Some Mexican cartels have begun human trafficking as drug operations are disrupted. Newsweek. https://www.newsweek.com/some-mexican-cartels-have-begun-human-trafficking-drug-operations-are-disrupted-1501258

U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration. (2021, January 28). Violent drug organizations use human trafficking to expand profits. DEA. https://www.dea.gov/stories/2021/2021-01/2021-01-28/violent-drug-organizations-use-human-trafficking-expand-profits

Reuters. (2020, April 24). Drugs, oil, women: Mexican cartels turn to human trafficking. Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-mexico-trafficking-moneylaundering-tr/drugs-oil-women-mexican-cartels-turn-to-human-trafficking-idUSKBN22B2TG/