EP97: Who Killed Haiti? The Complex Web Behind a Nation's Downfall

The Gangland Nation: Inside Haiti’s Desperate Struggle for Control

Introduction:

Haiti, a nation of profound historical significance and remarkable resilience, now stands yet again at a critical crossroads, grappling with deep-seated challenges that threaten its very existence as a functional state. From its proud history as the first independent black-led republic to its current struggle against political instability, rampant gang violence, economic collapse, and humanitarian crises, Haiti's trajectory is emblematic of the complex interplay between colonial legacies, internal governance failures, and external interventions.

This paper delves into the myriad factors contributing to Haiti's descent into state failure, seeking to unravel the historical, political, socio-economic, and international dimensions of its ongoing crisis. By examining pivotal moments such as the aftermath of the Haitian Revolution, the enduring economic repercussions of colonial reparations, the assassination of President Jovenel Moïse, and the rising dominance of armed gangs, this analysis provides a comprehensive lens through which to understand Haiti's precarious present. Furthermore, the paper explores the critical role of international interventions, their limitations, and the broader implications of Haiti's plight for the global community.

In navigating the complexity of Haiti's crisis, this study aims not only to dissect the root causes but also to shed light on the urgent need for sustainable solutions that address both immediate challenges and the deeper structural issues that have long plagued the nation. Ultimately, it raises the essential question: Can Haiti reclaim its sovereignty and stability, or is it destined to remain a cautionary tale of state failure in the modern era?

Abstract:

Haiti, once celebrated for its historical significance as the first black-led republic and independent state in the Caribbean, is currently experiencing profound political, economic, and social turmoil. This paper examines the historical, political, and socio-economic factors that have contributed to Haiti's contemporary state of near-collapse, exploring how these elements have converged to create one of the most acute crises of governance in the modern world.

Introduction:

Haiti's journey from colonial prosperity to a state teetering on the brink of failure is a complex narrative shaped by centuries of systemic challenges. This paper seeks to dissect the layers of historical baggage, political instability, economic despair, and social disorder that have culminated in the current crisis.

Historical Context:

The roots of Haiti's current predicament can be traced back to its colonial past under French rule as Saint-Domingue, one of the richest colonies due to its sugar production. The Haitian Revolution of 1804, led by figures like Toussaint L'Ouverture, not only ended slavery but also established Haiti as a beacon of freedom. However, this freedom came at a steep price. France demanded reparations for lost property (including former slaves), which Haiti paid until 1947, severely hampering its economic development. This debt, alongside international isolation, set a precedent for economic struggles that persist.

Political Instability:

The assassination of President Jovenel Moïse in July 2021 marked a significant downturn in Haiti's political stability.

(Pictured above is Jovenel Moïse)

The assassination is still considered an active investigation. The complexity of the plot, involving both local and foreign actors, underscores the multifaceted nature of Haiti's political and security landscape. There is a lot of speculation. The list of primary suspects include Columbian mercenaries, Haitian-Americans and local facilitators. A group of approximately 26 former Colombian soldiers were directly involved in the execution of the attack. These mercenaries were allegedly hired to carry out the assassination, with several arrested shortly after the event. Among the indicted were James Solages and Joseph Vincent, both Haitian-Americans, who acted as interpreters or coordinators for the Colombian team. Individuals like Rodolphe Jaar, a Haitian-Chilean businessman, played pivotal roles by providing logistical support, including housing and weapons for the Colombians involved in the plot.

In February 2024, a Haitian judge's final report indicted several high-profile figures, including Martine Moïse, the president's widow, former Prime Minister Claude Joseph, and ex-Chief of Police Léon Charles, for complicity and criminal association. This reflects a broader conspiracy involving both political and security elites.

The why is even more complicated. One theory suggests that the assassination was orchestrated to create a power vacuum, which could be exploited by political rivals or factions. The lack of a clear successor or stable government post-assassination hints at this motive. Some involved, particularly the businessmen implicated, might have anticipated lucrative government contracts under a new regime. The plot evolved from an initial plan to kidnap Moïse into an assassination, possibly to expedite a change in leadership for personal or business gain. A pastor with political ambitions, Christian Emmanuel Sanon was accused of having aspirations to replace Moïse. He was linked to the plot through his association with the security companies involved, though he claimed he was misled about the true intent of the operation. Moïse's tenure was marked by controversy, including allegations of corruption, his rule by decree after the dissolution of parliament, and his efforts to amend the constitution, which could have motivated opposition from various quarters, including within the political elite or security forces. The probe in Haiti has been criticized for its slow pace, with multiple judges stepping down due to threats and security concerns. This has led to limited progress in identifying the masterminds or providing a comprehensive motive. The involvement of U.S. authorities, particularly through arrests and convictions in Florida, has provided some clarity on the operational aspects of the assassination but less so on the higher-level orchestration.

Since then, the absence of democratically elected officials, with the last leaving office in January 2023, has left a governance vacuum. Ariel Henry, appointed as interim Prime Minister, has not been able to organize elections, further destabilizing the nation. His perceived illegitimacy has fueled public distrust, exacerbating the political crisis. Ariel Henry is no longer in charge of Haiti as he formally resigned on April 24, 2024, after a transitional presidential council was established. Prior to his resignation, Henry had been unable to return to Haiti due to gang violence and was stranded in Puerto Rico since early March 2024. His resignation was part of an agreement following international and domestic pressure due to the escalating gang violence and political crisis in Haiti. Since his resignation, Michel Patrick Boisvert has been serving as the acting Prime Minister until a new government can be formed but was forced to resign on June 3, 2024. Since June 3, 2024, Garry Conille has been serving as the interim Prime Minister of Haiti.

Garry Conille was born in Haiti but spent a significant part of his life in the United States. He holds a medical degree from Université de Montréal, Canada, and has pursued further education in public health, earning a Master's from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and a Doctorate in Public Health from the same institution. Conille's career began in medicine, working in Haiti's healthcare sector. His focus later shifted towards public health, where he contributed to national health programs and policies aimed at improving health outcomes in Haiti. He served as the Regional Director for Latin America and the Caribbean at the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA), where he was involved in managing reproductive health and population issues across the region. Conille also worked with the United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF), focusing on health and nutrition programs in Haiti. Conille first entered Haitian politics when he was appointed Prime Minister in 2011 under President Michel Martelly. His term was marked by efforts to reform public administration, fight corruption, and stabilize the government post the 2010 earthquake. However, his tenure was short-lived, resigning in 2012 amidst political tensions. After leaving political office, Conille resumed his international career, serving as the Chief of Staff to the Regional Director of the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO/WHO). Conille's re-emergence in Haitian politics came in June 2024 when he was appointed as interim Prime Minister. His selection was part of a broader effort to stabilize the country through a transitional presidential council, following the resignation of Ariel Henry and amidst increasing gang violence and political disarray.

(Pictured above Garry Conille)

Alix Didier Fils-Aimé (born 14 November 1971) is a Haitian businessman who was appointed on November 10, 2024, is the interim prime minister of Haiti. He pursued higher education in the United States, earning a degree in business management with a specialization in finance from Boston University. Fils-Aimé has been deeply involved in Haiti's business community, owning multiple enterprises. He is notably known for his chain of dry-cleaning stores, Blanchisserie du Soleil, which has contributed to his reputation as a successful businessman. He served as president of Haiti's Chamber of Commerce under former President Michel Martelly, indicating his engagement in economic governance and policy-making. From 1999 to 2011, he was the president of Hainet, one of Haiti's major internet service providers, demonstrating his involvement in the country's burgeoning technology sector. Fils-Aimé is also a founding member of the Association Haïtienne des Entreprises de Technologies de l’Information et de la Communication (AHTIC), aimed at promoting ICT in Haiti. Fils-Aimé ran unsuccessfully for a seat in the Haitian Senate in 2015 under the Vérité Party, showing his prior interest in political leadership.

(Pictured above is Alix Didier Fils-Aimé)

Who is next as it seems the prime minister seat hardly gets warm before the Haitian Transitional Presidential Council is quick to dismiss?

Gang Violence and Control:

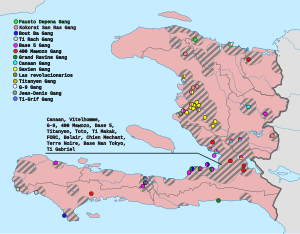

The power vacuum has been exploited by armed gangs, which now control approximately 80% of Port-au-Prince. Their activities, ranging from kidnappings to blockading critical infrastructure, have crippled both the economy and humanitarian aid efforts. A disturbing symbiosis has developed between these gangs and political elites, with the latter often supporting the former to maintain power or gain advantage, thus embedding criminality within the governance structure.

(Map of Gang Clashes between 2023 and 2024)

The Major Gangs

G9 Family and Allies (G9):

The G9 Family and Allies, commonly known as G9, is led by Jimmy Chérizier, who goes by the alias "Barbecue." Chérizier, a former police officer, has become a prominent gang leader since forming the G9 coalition in 2020. He has been sanctioned by both the United Nations and the United States due to his involvement in human rights abuses. The G9 operates in key regions such as Delmas, Croix-des-Bouquets, and Cité Soleil. Their activities include blockading fuel terminals to control access to vital resources, and they are often engaged in intense turf wars with rival gangs.

(Pictured above Jimmy Chérizier)

G-Pèp:

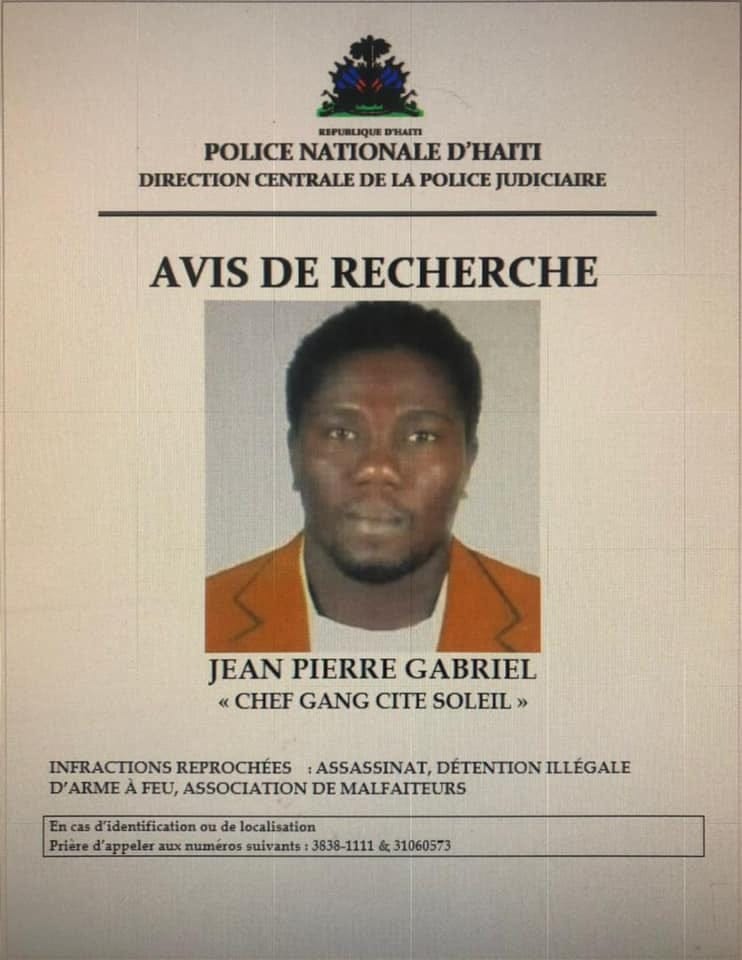

Leading G-Pèp, or G-Pèp, is Jean Pierre Gabriel, alias "Ti Gabriel," who previously controlled the Nan Brooklyn area in Cité Soleil. His background is rooted in local power struggles within this impoverished district. G-Pèp maintains a significant presence in Cité Soleil, where they frequently clash with G9 over territorial control. They are known for their violent methods, which include mass shootings and extortion, making them a formidable force in Haiti's gang landscape.

Viv Ansanm (Living Together):

Viv Ansanm operates more as a coalition than a single gang, comprising members from G9 and various smaller gangs. Jimmy Chérizier has emerged as a key figure in coordinating this alliance, aiming to unite different groups in opposition to the Haitian government. Their operations have included coordinated attacks on police stations, prisons, and efforts to disrupt governmental functions, notably during the political upheavals of early 2024.

400 Mawozo:

Joly Germine, now imprisoned in the U.S. after pleading guilty to arms smuggling, leads the 400 Mawozo gang. This group gained international infamy following the 2021 kidnapping of 17 missionaries. Based primarily in Croix-des-Bouquets, 400 Mawozo engages in high-profile kidnappings for ransom and has established connections with criminal networks outside of Haiti, expanding their influence beyond local conflicts.

(Pictured above in white and in handcuffs is Joly Germine who was sentenced to served 35 years)

Other Notable Gangs:

Base Nan Grif:

They are known for violent crimes and controlling parts of the Cité Soleil but less centralized under a single leader in recent reports.

Ti Bwa:

They operates in the Martissant area, known for highway robberies and territorial control.

These gangs have carved out zones of influence, often dictating local governance, extortion, and providing or denying access to services like water, electricity, and food.

Analysis of Gang Leadership and Structure:

Leaders like Chérizier have managed to portray themselves as community protectors or revolutionaries, despite their criminal activities, which complicates public perception and law enforcement efforts. These gangs by and large operate with a hierarchical structure, often recruiting from disenfranchised youth, offering them protection, money, or a sense of belonging in a country with high unemployment and poverty.

Economic and Humanitarian Crisis:

Haiti's economy is the weakest in the Western Hemisphere, with widespread poverty, high unemployment, and a critical dependence on foreign remittances and aid. The situation has been worsened by natural disasters, notably the devastating 2010 earthquake, and recurring hurricanes, leading to severe food insecurity and health crises, including cholera outbreaks.

International Involvement and Criticism:

International interventions, including UN peacekeeping missions, have historically been fraught with issues, from introducing cholera to allegations of sexual misconduct by peacekeepers. The proposal for a Kenyan-led force to combat gang violence has met with skepticism due to these past failures and a general resistance to foreign intervention in Haitian society. There's a strong sentiment for self-driven solutions, highlighting a complex relationship with international aid.

Haiti’s previous engagements with UN peacekeeping missions, like MINUSTAH (2004-2017) and MINUJUSTH (2017-2019), provide a backdrop for understanding current issues. Previous UN missions were criticized for incidents like the cholera outbreak and sexual abuse scandals, which have left a lasting distrust among Haitians towards foreign interventions. The Kenyan-led Multinational Security Support (MSS) mission authorized in 2023 has been severely underfunded compared to the scale of Haiti's security needs. Only a fraction of the required $600 million has been pledged, limiting the mission's operational capacity. There has been a significant delay in deploying the full complement of forces, with only a small number of Kenyan police arriving, which has not been enough to make a tangible difference on the ground. The mission's focus on policing rather than military intervention has not been robust enough to tackle the level of violence and control by these gangs. The absence of a legitimate and effective government has hampered coordination with the UN mission. The political instability, with no elected officials since early 2023, has meant that there's no clear governmental partner for the mission to work with. There is considerable local resistance to foreign intervention due to past experiences, leading to a lack of public support or cooperation with the UN mission. Haitians advocate for solutions led by Haitians, which complicates the mission's legitimacy and operational effectiveness. The MSS mission was given a mandate to support rather than lead security efforts, which has confined its actions to training and support roles, potentially underestimating the immediate need for direct intervention against gang violence. There's a lack of unified international support for the mission, with some nations hesitant to commit resources or personnel due to the perceived high risk and limited success of previous interventions. Neighboring countries and regional bodies like CARICOM have expressed support but have not provided substantial on-the-ground assistance, leaving the mission somewhat isolated in its efforts.

(Pictured above: Kenyan officer Godfrey Otunga, head of the Kenyan mission in Haiti from the newly-arrived United Nations Multinational Security Support (MSS) mission salutes Haitian and Kenyan officials during their visit to the MSS base on June 26, 2024.)

Haiti a Failed State?

According to political theories, particularly Max Weber's, a state is considered failed when it cannot perform basic functions like taxation, law enforcement, security, territorial control, and infrastructure maintenance. Additional signs include widespread corruption, humanitarian crises, and external military intervention. There have been no elections since 2016, severely undermining democratic governance and legitimacy. The Haitian National Police are significantly outgunned and outnumbered, unable to maintain law and order. Haiti clearly exhibits a loss of control over significant portions of its territory, with gangs acting as parallel governance structures. The state has lost its monopoly on violence, a fundamental aspect of statehood according to Weberian theory. There's an evident collapse of state institutions, with corruption, lack of legal governance, and no effective civil administration. The state's inability to provide for its citizens' basic needs aligns with the humanitarian aspect of state failure. Considering the criteria and characteristics of a failed state, Haiti does indeed meet the definition due to its inability to govern effectively, provide security, maintain territorial integrity, and ensure basic services for its population. The pervasive control by armed gangs, coupled with a non-functioning government, economic collapse, and ongoing humanitarian crises, collectively justify the classification of Haiti as a failed state.

Haiti’s Bleak Future

Over the next year, Haiti will likely continue to grapple with governance issues. The transitional government under Alix Didier Fils-Aimé may struggle to consolidate power or legitimize its rule without elections, potentially leading to further political fragmentation or increased gang influence in governance vacuums. Who knows how long he will last in the top spot? The dominance of armed gangs, particularly in Port-au-Prince, seems set to persist or even intensify, unless there's a significant and effective international intervention or a robust local security response. Humanitarian crises, including food insecurity and health emergencies, are expected to continue due to disrupted governance and economic activities. International aid might increase, but its effectiveness will depend on security conditions. The economy will remain in a precarious state, with little improvement expected in the short term due to ongoing security issues, lack of investment, and the need for extensive infrastructure repair.

An optimistic outlook for the next five years is more the same. Absent strong military intervention to assault the gangs and restore the rule of law and the government as the only legitimate actor with monopoly over violence, this state is not going to change. Plus, there needs to be a wide scale removal of corrupt politicians who are supported or who are intimidated by the gangs. This does not appear to be something that Haiti can do on its own. Without significant international intervention or local consensus, political fragmentation could intensify. The transitional government might not hold, leading to a complete collapse of state structures, with no elections held, resulting in a power vacuum exploited by various factions. Gangs could further entrench their control, not just in Port-au-Prince but across Haiti. The absence of a functioning state might lead to gang federations, where different groups control various regions, leading to continuous conflict over territory and resources. Economic conditions could deteriorate further. Foreign investment would likely dry up due to the security situation, and local businesses might either close or operate under gang protection, leading to a shadow economy. The country might become more reliant on remittances and illicit activities for survival. With state services non-existent, humanitarian conditions would worsen significantly. Food insecurity, health crises like cholera, and displacement could become chronic issues, with aid agencies facing insurmountable challenges in delivering help due to security risks. There might be a growing international fatigue in dealing with Haiti, leading to reduced aid and intervention efforts, making the situation even more dire.

Over a decade, Haiti might transition from a failing state to a permanently failed one, where the concept of a central government becomes increasingly irrelevant. Local or regional warlords could emerge, each controlling their fiefdoms with little regard for national unity. Gangs could evolve into quasi-governmental entities, providing some form of order or services in exchange for control and allegiance. This could lead to a normalization of violence and crime as the primary means of social organization. The economy might stagnate or decline to subsistence levels. Legal economic activities would be overshadowed by informal and illegal ones, with Haiti potentially becoming a hub for drug trafficking or other criminal enterprises as legitimate trade routes collapse. Continuous violence and lack of opportunities might lead to a significant exodus of the population, either internally or internationally, further draining Haiti of human capital and exacerbating the humanitarian crisis within the country and creating pressure on neighboring states. The social fabric could unravel with the loss of educational and cultural institutions, leading to a generation growing up with limited opportunities for education or cultural expression, further entrenching poverty and despair. Haiti might become increasingly isolated on the international stage, with countries either unable or unwilling to engage due to the complexity and risks involved, thus deepening the cycle of neglect and crisis. It could provide a local breading ground for extremist groups who might under the most worst case scenario seek to branch its violence outside of Haiti to other countries.

Lack of International Resolve:

Haiti does not possess significant quantities of the resources typically driving international interest, such as oil, minerals, or rare earth elements. While it has some agriculture and minor mining activities, these do not compare to resource-rich nations that often see intervention for economic gain. Haiti's main exports like mangoes, coffee, and vetiver oil are not enough to spur significant international economic interest compared to other global commodities. Although there are some mining activities, the scale and profitability do not match regions like Africa or Latin America, where mining is a major economic driver. While geographically close to the U.S., the strategic importance of Haiti in terms of global geopolitics is limited. The U.S. has historically intervened but often with mixed motivations, more about regional stability rather than resource extraction. Neighboring countries and regional bodies like CARICOM have limited capacity or willingness to lead interventions, and larger global powers might prioritize other international crises. The financial, human, and political costs of intervention in Haiti, given its complex socio-political landscape, might outweigh perceived benefits, especially when compared to regions where intervention could yield more direct geopolitical or economic gains. After decades of aid with little visible progress, there's a potential for donor fatigue among international actors, questioning the effectiveness of further interventions. There's significant local resistance to foreign intervention based on historical precedents, complicating any international action with local legitimacy issues. With numerous global crises, including conflicts in Europe and the Middle East, Haiti might not capture the same level of international attention or urgency. There's an increasing emphasis on respecting national sovereignty and promoting solutions led by the affected countries themselves, leading to hesitance in imposing external solutions. Plus, Americans still have long memories involving what started out as humanitarian aid but turned into the Battle of Mogadishu in Somalia.

Conclusion:

Haiti's current state of near-collapse reflects the cumulative impact of centuries of systemic challenges, from colonial exploitation and international isolation to persistent political instability and economic stagnation. Its struggles are a stark reminder of how historical injustices, weak governance, and socio-economic disparities can intertwine to create an enduring cycle of fragility. The country's inability to provide basic security, infrastructure, and governance has eroded public trust, leaving a vacuum increasingly filled by armed gangs and criminal networks.

International interventions, while well-intentioned, have often been marred by a lack of cultural understanding, strategic missteps, and unintended consequences, further complicating Haiti's path toward recovery. The failures of past engagements underscore the need for a fundamentally new approach—one that prioritizes long-term capacity building, respects Haitian agency, and fosters inclusive governance. However, this approach requires sustained global commitment, something Haiti has struggled to secure amid competing international priorities and has not demonstrated that it even wants.

Haiti's future hinges on addressing its most pressing challenges: restoring governance through credible elections, dismantling the entrenched power of gangs, and rebuilding an economy capable of providing opportunities for its citizens. These goals are daunting and will require a coordinated effort among Haitian leaders, civil society, and the international community. Yet, without decisive and comprehensive action, Haiti risks becoming a permanently failed state, with consequences that extend beyond its borders possibly.

Sources:

https://news.un.org/en/story/2024/11/1157131

https://news.miami.edu/stories/2024/03/haiti-is-close-to-becoming-a-failed-state.html

https://www.chathamhouse.org/2024/03/time-haiti-really-brink-us-and-un-must-act-restore-order

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2023/jan/12/haiti-crisis-jovenel-moise-gangs-water-way-out

https://www.essex.ac.uk/blog/posts/2024/04/04/how-haiti-became-a-failed-state

https://www.hrw.org/news/2024/03/08/haiti-urgent-action-needed-amid-growing-lawlessness

https://theconversation.com/how-haiti-became-a-failed-state-225116

https://www.hrw.org/world-report/2022/country-chapters/haiti

https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/c4gx7gjv22po

https://www.nytimes.com/2024/11/10/us/haiti-prime-minister-garry-conille-fired.html

https://apnews.com/article/haiti-new-prime-minister-council-gangs-0ea9537996c9550ba70fa66dfe58b459

https://www.bbc.com/news/world-latin-america-57762246

https://insightcrime.org/news/takeaways-haiti-investigation-jovenel-moise-murder/

https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/additional-four-charged-connection-plot-kill-haitian-president

https://globalinitiative.net/analysis/haiti-gangs-organized-crime/

https://www.nytimes.com/2024/03/07/world/americas/haiti-gangs-explainer.html

https://www.pbs.org/newshour/world/gangs-take-control-in-haiti-as-democracy-withers

https://www.globalr2p.org/countries/haiti/

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2024/jan/18/haiti-residents-trapped-port-au-prince-gangs

https://news.un.org/en/story/2022/05/1118432

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2022/sep/18/haiti-violence-gang-rule-port-au-prince

https://slate.com/podcasts/what-next/2024/03/how-haitis-gangs-took-hold-of-port-au-prince

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2023/apr/30/haiti-port-au-prince-violence-gangs-police