Erasing Identity: A Deep Dive into the Uyghur Repression

From Re-education Camps to Forced Labor: The Uyghur Tragedy

TL;DR:

Who are the Uyghurs? A Turkic Muslim ethnic group primarily residing in Xinjiang, China, with a rich cultural and historical identity shaped by Islam, the Silk Road, and Central Asian traditions.

Current Situation: Allegations of mass internment, forced labor, and cultural genocide by the Chinese government under the guise of "anti-terrorism" and "economic development" policies. Over 1 million Uyghurs detained in "re-education camps," facing cultural assimilation, forced sterilization, and religious repression.

Cultural Suppression: Prohibition of Uyghur language in schools, destruction of mosques, and promotion of Han Chinese migration to Xinjiang to dilute Uyghur identity.

Forced Labor: Widespread reports of coerced labor in industries like cotton, textiles, and polysilicon, affecting global supply chains.

China’s Narrative: Framed as a fight against separatism, extremism, and terrorism, though international observers largely view these policies as oppressive.

International Response: Global condemnation, sanctions, and legislation like the U.S. Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act. Ongoing advocacy by Uyghur diaspora and NGOs to preserve culture and raise awareness.

Global Implications: Heightened scrutiny of supply chains, corporate ethics, and human rights in international trade.mPersistent tensions between economic ties to China and global calls for accountability.

Conclusion: The Uyghur situation highlights critical issues of cultural survival, human rights, and international justice. Global action and advocacy are key to supporting the Uyghur people and holding China accountable.

And now the Deep Dive….

Introduction

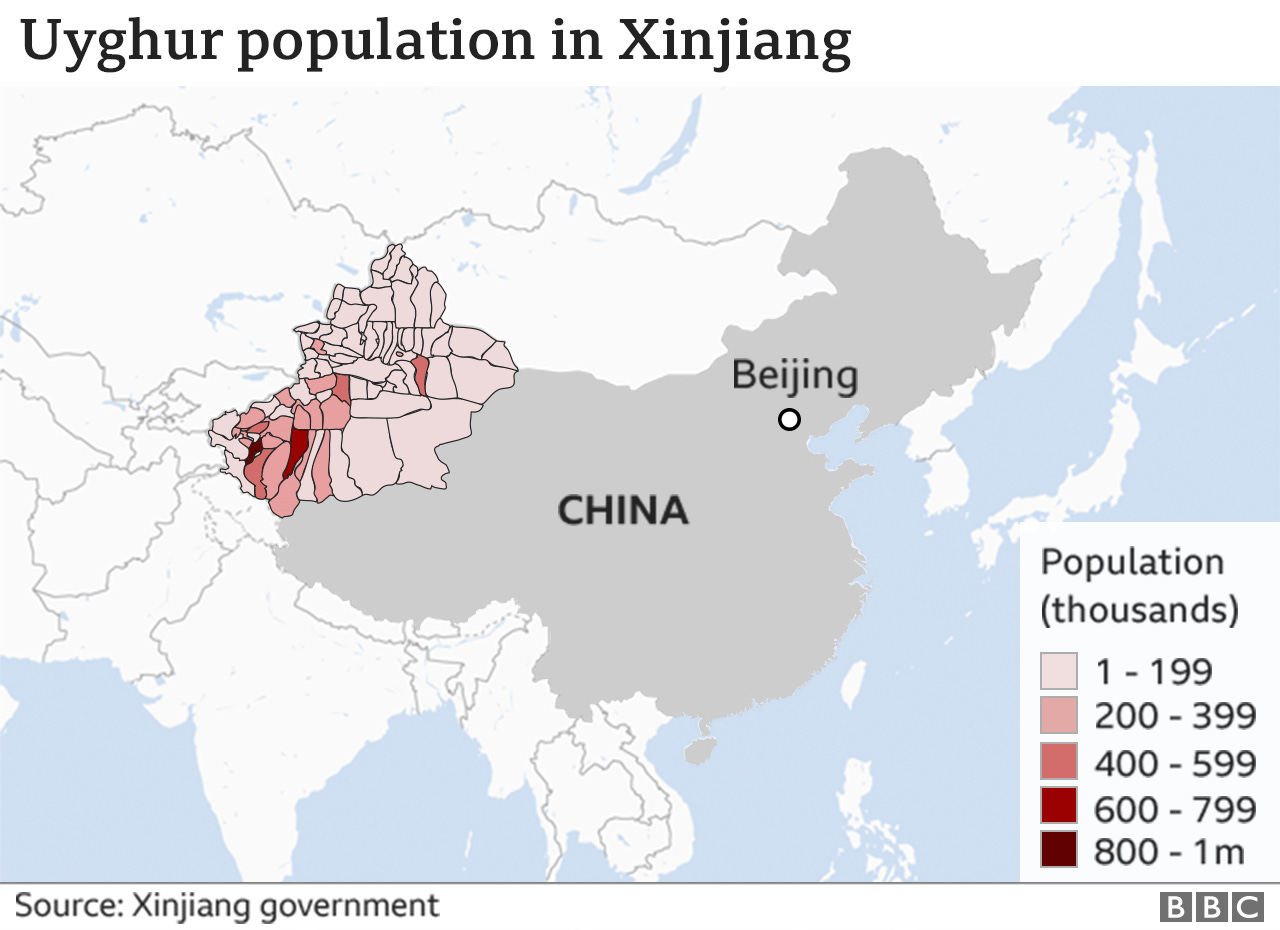

The Uyghurs are a Turkic Muslim ethnic group primarily residing in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region in Northwest China, a region that has been historically and culturally distinct from the rest of China due to its geographic location along the ancient Silk Road. This strategic positioning has made Xinjiang a focal point for both trade and geopolitical tensions. The Uyghurs, with a population of approximately 12 million, have been at the center of international attention due to allegations of human rights abuses by the Chinese government. These include mass detentions, cultural suppression, and what some international bodies and governments have labeled as genocide or crimes against humanity.

The current situation for the Uyghurs in China has been marked by significant tension and conflict, particularly since the implementation of what the Chinese government labels as "anti-terrorism" and "de-radicalization" policies. Since 2017, there have been widespread reports of mass internment camps where over a million Uyghurs are believed to have been detained. These camps, officially described as vocational training centers, have been criticized internationally for their conditions and the practices within, such as forced labor, cultural assimilation efforts, and religious restrictions, with many accounts suggesting severe human rights violations.

Cultural genocide is a term increasingly used by scholars and activists to describe the Chinese policies aimed at eradicating Uyghur cultural, linguistic, and religious identity. Practices such as the prohibition of Uyghur language in schools, the destruction of religious sites including mosques, and the imposition of Han Chinese cultural norms have been documented. The Chinese government's approach has included a systematic campaign to alter the demographic makeup of Xinjiang, encouraging Han Chinese migration to the region, which has led to Uyghurs becoming a minority in their traditional homeland.

We will examine this situation from every point of view in this article.

Who are the Uyghurs?

The Uyghurs are an ethnic group with roots tracing back to the ancient Turkic tribes that roamed Central Asia. Their history is deeply intertwined with the migration patterns that saw them settle in what is modern-day Xinjiang, China, around the 9th century following the collapse of the Uyghur Khaganate in Mongolia. The Uyghur language belongs to the Turkic language family, closely related to languages like Uzbek and belongs to the Karluk branch. Uyghurs primarily speak their native language, which is written in an Arabic script, reflecting their cultural and historical ties to broader Islamic traditions.

Islam is a central component of Uyghur identity, having been adopted by the majority of the population by the 16th century. The Uyghurs follow Sunni Islam, often with influences from Sufism, showcasing a blend of spiritual practices and local customs. This religious affiliation is not just a matter of faith but also a significant aspect of their cultural identity, influencing everything from their daily life to their festivals and community gatherings. However, under the current Chinese administration, there has been a concerted effort to limit Islamic practices, which has led to significant cultural and religious suppression.

Population estimates for Uyghurs vary, but they are one of the largest ethnic minority groups in China, with the majority residing in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region. Recent figures suggest a population of about 11 to 12 million in Xinjiang alone. Beyond China, there are substantial Uyghur communities in Central Asian countries like Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, and Uzbekistan, as well as in Turkey due to historical and cultural affinities. Smaller numbers of Uyghurs have also migrated to Europe, North America, and Australia, forming a diaspora that keeps the cultural heritage alive outside of China.

The cultural identity of the Uyghurs is rich and diverse, shaped by their history at the crossroads of the Silk Road. Uyghur art is noted for its vivid depictions in both painting and textiles, often featuring bright colors and intricate patterns that reflect both Islamic motifs and the ancient influences of the region's historical trade routes. Uyghur music is particularly celebrated, with the Muqam being one of the most prestigious musical forms, combining elements of song, dance, and poetry into a complex and expressive art form recognized by UNESCO as part of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity.

Traditional Uyghur practices are deeply connected to their nomadic and later settled lifestyle, involving unique festivals like the Nowruz, which marks the Persian New Year and is celebrated with feasts, dance, and music. Their cuisine is another vibrant aspect of their cultural identity, known for its hearty, flavorful dishes like polu (a type of pilaf), laghman (hand-pulled noodles), and an array of kebabs, reflecting the fusion of Central Asian and Middle Eastern culinary traditions.

The role of women in Uyghur society is traditionally significant, balancing between cultural norms and Islamic practices. Women participate actively in community life, including in the arts, where they are known for their skills in crafts like embroidery and weaving. However, recent policies in China have aimed at altering these traditional roles through forced assimilation, including promoting intermarriages with Han Chinese and imposing restrictions on religious and cultural expressions.

Despite these pressures, Uyghurs have strived to maintain their cultural identity. Festivals, traditional attire, and the use of the Uyghur language in public and private life are acts of cultural resistance. The diaspora communities play a crucial role here, preserving and promoting Uyghur culture through cultural centers, language schools, and by organizing cultural events that celebrate Uyghur heritage.

However, this cultural preservation is under threat within Xinjiang. The Chinese government's policies, often framed as efforts to combat extremism, have led to a significant erosion of Uyghur cultural practices. This includes the demolition of mosques, suppression of religious education, and the redefinition of Uyghur history in educational materials to align with the state's narrative, posing a profound challenge to the survival of Uyghur cultural identity.

Historical Presence in China

The Uyghur presence in the region now known as Xinjiang dates back to ancient times. Initially, the Uyghurs were part of a nomadic confederation known as the Uyghur Khaganate, established around 744 AD in the Mongolian steppes. This empire was significant not only for its military prowess but also for its cultural contributions, particularly in the arts and sciences. The collapse of the Khaganate in the 9th century due to internal strife and external pressures from the Kyrgyz led to migrations westward into the Tarim Basin, where they gradually settled among the oasis towns of what is now Xinjiang.

During the Tang Dynasty (618-907 AD), the Uyghurs had already begun to interact with Chinese civilization, participating in the Silk Road trade and even playing pivotal roles in military alliances against common enemies like the Tibetans. By the time of the Song Dynasty (960-1279 AD), Uyghurs had established themselves as merchants and artisans in major Chinese cities, while in Xinjiang, they were developing their own states, like the Qocho kingdom, which was culturally and linguistically Turkic but heavily influenced by Buddhism and Manichaeism before the spread of Islam in the region.

The Mongol Yuan Dynasty (1271-1368 AD) further integrated the Uyghurs into Chinese political and cultural spheres, with many Uyghurs serving in high administrative positions. However, the fall of the Yuan and the rise of the Ming Dynasty saw a decline in Mongol influence, leading to a period where Uyghurs were more on the periphery of Chinese power. The Qing Dynasty (1644-1912 AD), in its expansion westward, conquered Xinjiang in the 18th century, formally incorporating it into China, though governance remained somewhat loose, allowing for a degree of cultural autonomy.

The modern history of Uyghurs in China took a significant turn with the establishment of the People's Republic of China in 1949. That year also saw the creation of the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region (XUAR), designed to recognize the ethnic diversity of the region while ensuring Chinese control. Initially, the autonomy was more substantial, with Uyghurs holding key political positions, and there was a cultural renaissance with Uyghur literature, music, and arts flourishing. However, this autonomy was always under the overarching authority of the Communist Party, which gradually tightened its grip.

From the 1950s through the 1970s, the policies towards Xinjiang oscillated between periods of relative liberalization and harsh crackdowns, notably during the Cultural Revolution when cultural practices were persecuted. Post-Mao, under Deng Xiaoping's reforms, there was another attempt at economic development and cultural preservation, but this was coupled with increasing Han Chinese migration into Xinjiang, altering the demographic balance.

The 1990s and early 2000s saw growing ethnic tensions, with incidents like the Baren Township unrest in 1990 and the Ghulja Incident in 1997, where protests for cultural rights were met with forceful government responses. These events marked a shift towards more stringent security measures under the guise of combating separatism, religious extremism, and terrorism, especially after 9/11 when China aligned its policies with global counter-terrorism efforts.

Since 2017, under Xi Jinping's leadership, the autonomy of the XUAR has arguably diminished further with the implementation of what has been described as a mass surveillance state and the establishment of "re-education" camps. These policies aim at assimilating Uyghurs into the broader Chinese cultural and political framework, often at the cost of their traditional practices, language, and religion. The creation of these camps has led to international outcry, with accusations of human rights abuses, forced labor, and cultural genocide.

The historical presence of Uyghurs in Xinjiang has been marked by periods of both cultural flourishing and severe repression. From their ancient roots as a nomadic empire to their integration into various Chinese dynasties, and through to the modern autonomous region, the trajectory of Uyghur autonomy has been fraught with complexities that reflect broader issues of cultural identity, governance, and human rights in contemporary China.

China's Stance on Uyghurs

The geopolitical landscape of China's Xinjiang region, where the majority of Uyghurs reside, is deeply intertwined with concerns over national unity and stability. Historically, there have been movements among the Uyghurs for greater autonomy or outright independence, often framed around the concept of "East Turkestan." These separatist sentiments have roots in the early 20th century with the establishment of two short-lived East Turkestan Republics in the 1930s and 1940s. More recent movements have been influenced by the collapse of the Soviet Union and the independence of neighboring Central Asian states, which inspired some Uyghur nationalists to push for similar self-governance. However, these movements have been met with strong resistance from the Chinese state, which views any form of separatism as a direct threat to its territorial integrity.

On the cultural front, China's policies towards the Uyghurs have increasingly focused on integration into the dominant Han Chinese culture. This has been executed through educational reforms that emphasize Mandarin over Uyghur in schools, aiming to create a bilingual populace with a strong inclination towards the national language and culture. These policies are part of a broader "Sinicization" effort, where cultural practices, including religious ones, are heavily regulated or outright banned if seen as incompatible with Chinese state ideology. This includes restrictions on religious education, fasting during Ramadan, wearing traditional Islamic attire, and even the architectural style of mosques, which are often altered or demolished to fit a more "Chinese" aesthetic or repurposed as tourist sites.

The Chinese government frames its stance on Uyghur issues predominantly through the lens of combating terrorism, separatism, and religious extremism, which it collectively refers to as the "three evils." The narrative positions any form of Uyghur activism or cultural expression that does not align with state policy as potential threats to national security. Following the 9/11 attacks, China capitalized on the global "war on terror" to justify its stringent measures in Xinjiang, equating Uyghur unrest with international terrorism. This has led to the establishment of what China officially terms as "vocational education and training centers," but which are internationally criticized as internment camps where millions of Uyghurs have reportedly been detained.

The official narrative from Beijing insists that these measures are necessary for the stability and economic development of Xinjiang. The government claims that its policies have brought peace, with no significant terrorist attacks reported in recent years, attributing this to their stringent security measures. However, this stability is often criticized as being achieved through oppressive means that suppress Uyghur identity, leading to accusations of cultural genocide. The government's portrayal of these camps as places for re-education and vocational training is meant to counter international critique by suggesting that they serve to integrate Uyghurs into the economic fabric of China, reducing poverty and radicalization.

Cultural integration efforts are also seen through the lens of economic development, where the state promotes the idea that by adopting Han culture and language, Uyghurs will benefit economically. This includes encouraging inter-ethnic marriages and incentivizing Han Chinese to move to Xinjiang under various development programs, which not only alter the demographic composition but also aim to dilute Uyghur cultural identity. Critics argue that this is forced assimilation rather than voluntary integration, with cultural practices being systematically eradicated.

The Chinese government's approach has been to control the narrative both domestically and internationally. Within China, state media often portrays Uyghur separatists as terrorists, and reports from Xinjiang are heavily censored or curated to show only the "positive" aspects of government policy. On the global stage, China uses its economic clout and diplomatic relations to deflect criticism, often labeling foreign critiques as interference in its internal affairs or accusing critics of having ulterior motives, like tarnishing China's image to hinder its global rise.

Despite these efforts, the international community has not remained silent. Various countries, particularly Western nations, have condemned China's actions, with some officially recognizing them as genocide or crimes against humanity. This has led to diplomatic tensions, with sanctions imposed on Chinese officials and companies linked to the abuses in Xinjiang. However, China's narrative continues to find support in countries that are economically tied to or geopolitically aligned with China, showcasing the complex interplay of international politics and human rights concerns.

China's stance on the Uyghurs is a multifaceted issue involving deep-seated geopolitical, cultural, and security concerns. The government's narrative of anti-terrorism and stability maintenance overshadows the cultural erosion and human rights violations reported by numerous international observers, creating a stark divide in global perceptions and responses to the situation in Xinjiang.

Forced Labor and Human Rights Violations

The Chinese government has implemented “labor transfer programs” as part of its broader strategy to manage and integrate the Uyghur population into the national economy and political system. These programs involve relocating Uyghurs from rural areas in Xinjiang to urban centers or factories across China, ostensibly to alleviate poverty and provide employment opportunities. However, critics argue these transfers are coercive, with Uyghurs often having little choice in the matter, facing penalties like detention or further scrutiny if they refuse. The aim is to assimilate Uyghurs into Han Chinese society, reducing cultural, religious, and linguistic differences under the guise of economic development. These transfers have been reported to occur both within Xinjiang and to other provinces, with workers sometimes living in controlled environments, such as segregated dormitories, where they are subjected to surveillance and ideological indoctrination.

The internment camps, officially called "Vocational Education and Training Centers," represent one of the most contentious aspects of China's policy towards Uyghurs. Since 2017, it is estimated that over a million Uyghurs and other Muslim minorities have been detained in these facilities for what the Chinese government describes as re-education to combat extremism. Inside these camps, detainees are subjected to a regimen of political indoctrination, where they must learn Mandarin, pledge loyalty to the Communist Party, and renounce their religious beliefs. Conditions within the camps have been described as harsh, with numerous accounts of psychological and physical abuse, including torture, forced sterilization, and sexual abuse. Testimonies from former detainees paint a picture of a system designed not just to educate but to break down individual and cultural identity.

Human rights violations within these camps are severe and well-documented by international organizations and media. Reports have described overcrowded cells, lack of due process, and the absence of any legal framework for these detentions. Detainees are often held without charge, with their families having little or no information about their whereabouts or conditions. The psychological toll includes forced confessions and self-criticism sessions, aimed at eradicating any form of dissent or cultural separation from the Chinese state's vision of a unified nation under Han Chinese cultural norms.

One of the most significant sectors where forced labor has been alleged is the cotton industry. Xinjiang produces a significant portion of the world's cotton, and there's substantial evidence suggesting that much of this cotton is harvested by Uyghur labor under coercive conditions. Uyghurs have been reported to be forced into picking cotton during peak seasons, with little to no pay, under strict surveillance, and with their movements heavily restricted. This has led to international campaigns against using Xinjiang cotton, with some countries imposing bans on imports to avoid complicity in forced labor practices.

Beyond agriculture, the solar energy sector has also been implicated in forced labor practices. Xinjiang is a key producer of polysilicon, a critical component in solar panels, and there are allegations that this production involves labor from detained Uyghurs. The supply chain for solar energy products is complex, and while some companies have started to audit their supply chains, the opaque nature of these chains makes it challenging to ensure that products are free from forced labor. This has raised ethical concerns for companies and consumers worldwide as they grapple with the implications of green technology potentially linked to human rights abuses.

Manufacturing, particularly in the garment industry, has also come under scrutiny. Global brands have been linked to factories in China where Uyghurs are allegedly employed under forced conditions. The transfer of Uyghurs to factories both in Xinjiang and beyond often involves conditions akin to those in the camps, with workers living in controlled environments, subjected to surveillance, and facing severe repercussions for non-compliance. These allegations have led to significant corporate accountability movements, with brands facing pressure to ensure their supply chains are free from forced labor.

The international response to these reports has been varied. Some countries have passed laws like the Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act in the United States, which presumes that goods from Xinjiang are produced with forced labor unless proven otherwise. This has led to increased scrutiny and customs holds on products from the region. However, the enforcement of such laws faces challenges due to the complexity of supply chains and the economic interdependence with China.

The allegations of forced labor and human rights violations in Xinjiang touch upon some of the most critical ethical and economic issues of our time. They challenge not only the moral standing of China's governance policies but also pose significant dilemmas for global trade, human rights advocacy, and the ethical sourcing of products in various industries. As the world becomes more interconnected, the response to these allegations will continue to shape international relations, corporate practices, and human rights discourse.

(Pictured above: Uyghur women pick cotton in Xinjiang. Rights groups have voiced concerns about forced labour in the region, photo credit: Getty Images)

Uyghurs and Terrorism

From the Chinese government's perspective, the narrative of combating terrorism in Xinjiang is central to justifying its stringent policies towards the Uyghur population. Since the early 2000s, particularly after the global "war on terror" gained momentum post-9/11, China has increasingly framed Uyghur activism and dissent as acts of terrorism. The government labels any form of Uyghur resistance, whether it is calls for greater autonomy, expressions of religious faith, or even peaceful protests, under the umbrella term of "the three evils" - separatism, religious extremism, and terrorism. This narrative has allowed Beijing to implement wide-reaching security measures, including mass surveillance, internment camps, and restrictions on cultural practices, all under the guise of national security and counter-terrorism efforts.

International views on China's portrayal of Uyghur-related activities as terrorism are mixed and often critical. Independent assessments by human rights organizations, scholars, and some governments suggest that while there have been instances of violence involving Uyghur individuals or groups, the scale and nature of terrorism in Xinjiang do not match the Chinese state's narrative. Many argue that the Chinese government exaggerates or mislabels acts of political dissent or cultural preservation as terrorism to legitimize its repressive policies. Reports from Amnesty International, Human Rights Watch, and other entities highlight that the majority of those detained in Xinjiang for terrorism-related activities have not undergone fair trials or were detained for non-violent expressions of their culture, religion, or identity.

Historically, there have been significant incidents that the Chinese government attributes to Uyghur separatist or extremist groups. One of the earliest notable events was the 1990 Baren Township uprising, where Uyghur rebels clashed with Chinese security forces, which was portrayed as an attempt to establish an independent Islamic state. The 1997 riots in Ghulja (Yining), protesting against religious restrictions, resulted in numerous deaths and was followed by a severe crackdown. More recently, the 2009 Ürümqi riots, initially sparked by ethnic tensions, led to hundreds of deaths, with China attributing the violence to Uyghur separatist groups. The government has also pointed to the 2014 Kunming railway station attack, where knife-wielding assailants killed dozens, and the 2013 Tiananmen Square car attack as evidence of Uyghur terrorism.

However, the international community has questioned the evidence linking these incidents directly to widespread, organized terrorism. Scholars like Sean Roberts and others have argued that many of these violent acts are more accurately described as responses to state repression rather than unprovoked terrorist campaigns. They suggest that the Chinese government's policies, which include cultural suppression and heavy-handed security measures, might actually fuel the very unrest they aim to quell. This perspective is supported by the fact that many of the attacks cited by China as terrorism were not part of a sustained campaign by any single, well-organized group but rather sporadic acts of violence by individuals or small, loosely connected groups.

The East Turkestan Islamic Movement (ETIM), now known as the Turkistan Islamic Party (TIP), has been the most cited Uyghur group in China's narrative of combating terrorism. However, the extent of this organization's influence and activities has been debated. The United States once listed ETIM as a terrorist organization but delisted it in 2020 due to lack of evidence of significant activity. This action cast doubt on China's claims of a rampant terrorist threat from Uyghur separatists.

Critics also argue that China's approach to counter-terrorism in Xinjiang involves tactics that are themselves human rights violations, including mass detentions without due process, torture, and cultural eradication. This has led to accusations that the "anti-terrorism" campaign is more about political control and cultural assimilation than genuine security concerns. The international backlash includes sanctions from various countries against Chinese officials and calls for boycotts of international events hosted by China over these policies.

Nevertheless, China uses international platforms to reinforce its narrative. At the United Nations and in bilateral talks, China often presents its actions in Xinjiang as a model for counter-terrorism, gaining support from some countries that are economically or politically aligned with China. This has led to a split in global responses, with some nations endorsing or at least not condemning China's approach, while others, particularly Western democracies, vehemently oppose it.

While there have been violent incidents involving Uyghurs in China, the characterization of these events as terrorism by the Chinese government is contentious. The broader international discourse suggests a need for a nuanced understanding that separates legitimate security concerns from the suppression of ethnic and religious identity. This debate touches on fundamental issues of human rights, state sovereignty, and the global fight against terrorism, with the situation in Xinjiang remaining a pivotal case study in this complex intersection.

(Pictured above: Satellite images show rapid construction of camps in Xinjiang, like this one near Dabancheng)

Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act (UFLPA)

The Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act (UFLPA) is a significant piece of U.S. legislation aimed at addressing the issue of forced labor in China's Xinjiang region. The Act was passed with overwhelming bipartisan support in Congress and was signed into law by President Joe Biden on December 23, 2021. Its primary objective is to combat the importation of goods made with forced labor, specifically targeting the systemic use of Uyghur forced labor in Xinjiang. The UFLPA introduces a legal presumption that all goods, wares, articles, and merchandise originating from Xinjiang or produced by entities on a designated list are made with forced labor unless proven otherwise by clear and convincing evidence. This legislation not only seeks to sever economic ties with forced labor but also aims to raise global awareness and pressure China to end these practices.

The implementation of the UFLPA is primarily handled by U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP), which enforces the act through a mechanism known as the "rebuttable presumption." Under this presumption, any product from Xinjiang or from companies listed under the UFLPA is automatically considered to be produced with forced labor and is thus prohibited from entry into the U.S. market unless importers can provide substantial evidence to the contrary. This includes supply chain tracing, documentation of labor conditions, and proof that no forced labor was used at any stage of production. CBP has detained numerous shipments since the act's enforcement began, affecting billions in trade, as it scrutinizes imports for compliance with this new standard.

The impact on trade has been substantial, particularly for sectors heavily reliant on Xinjiang's output, such as cotton, solar panels, and textiles. The UFLPA has led to increased costs for importers due to the need for extensive due diligence and has occasionally resulted in delays or outright bans on goods. Companies have had to overhaul their supply chain practices, often moving sourcing away from Xinjiang or demanding more transparency from their suppliers to ensure compliance. This has also had ripple effects on global supply chains, leading to price increases and shortages in certain products as businesses navigate the new regulatory landscape.

Globally, the UFLPA has served as a catalyst for similar legislative measures and corporate practices. Several countries have either passed or are considering laws modeled after the UFLPA to address forced labor in their supply chains. For instance, the European Union is advancing its own legislative framework to ban products made with forced labor. This movement is part of a broader trend where countries are increasingly linking trade policies with human rights, using economic leverage to promote better labor practices worldwide.

In terms of corporate due diligence, the UFLPA has pushed companies to reassess their supply chains more critically than ever. There has been a marked increase in ethical sourcing initiatives, with companies investing in technologies like blockchain for traceability and engaging third-party auditors to verify labor conditions. This act has heightened awareness of forced labor issues, encouraging corporations to adopt more robust human rights policies to mitigate risks not just in China but globally.

The UFLPA has also influenced international organizations and standards. The International Labour Organization (ILO) and the OECD have seen increased engagement with their guidelines on responsible business conduct, as companies seek to align with international norms to preempt similar domestic legislation. This has fostered a global conversation about how to balance economic interests with ethical considerations, particularly in light of the complexities of modern supply chains.

Moreover, the act has contributed to a diplomatic discourse, with nations using it as a point of leverage in discussions with China on human rights. It has brought the issue of Uyghur forced labor to the forefront of international diplomacy, although responses vary. Some countries have echoed U.S. concerns in international forums, while others, particularly those with significant economic ties to China, have been less vocal or have outright supported China's narrative.

The Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act has not only altered U.S. import practices but has also set a precedent that has begun to reshape global trade policies and corporate ethics. It has highlighted the interconnectedness of human rights and economic policy, pushing for a more ethical and transparent global marketplace where forced labor is no longer an acceptable cost of doing business.

International Response and Other Relevant Issues

The international community, through various United Nations bodies and non-governmental organizations (NGOs), has been actively documenting and critiquing the situation in Xinjiang. In August 2022, the Office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) released a comprehensive report detailing serious human rights violations, including possible crimes against humanity, in the region. This report highlighted issues like mass arbitrary detention, forced labor, and cultural repression. NGOs like Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International have been equally vocal, producing extensive research and testimonies that corroborate the UN's findings, emphasizing the scale of the abuses and calling for accountability. These organizations have been pushing for international mechanisms to investigate and address these violations, despite pushback from China.

In response to the situation in Xinjiang, several countries, notably the United States, Canada, the United Kingdom, and the European Union, have taken diplomatic and economic measures. The U.S. has implemented the Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act, which imposes sanctions on individuals and entities involved in human rights abuses in Xinjiang. Similarly, the EU, UK, and Canada have coordinated sanctions on Chinese officials and entities linked to these abuses, including travel bans and asset freezes. These actions not only signal international condemnation but also serve as attempts to leverage change in China's policies through economic and diplomatic pressure. However, these measures have also led to retaliatory actions from China, escalating tensions in international relations.

The UN's response has been complex, with calls for an independent investigation facing opposition due to geopolitical considerations. While some UN member states have supported these calls, others have either remained silent or endorsed China's narrative, showcasing the divide in international opinion. The UN Human Rights Council has been a battleground for this issue, with resolutions or special sessions being proposed but often facing procedural blocks by China's allies. The discourse at the UN thus reflects a broader geopolitical chess game where human rights are weighed against economic and political alliances.

Corporate accountability has become a significant aspect of the international response to Xinjiang. Multinational companies with supply chains connected to China, particularly those in industries like fashion, electronics, and solar energy, are under immense pressure to ensure they are not complicit in forced labor. This has led to a surge in corporate due diligence practices, with companies investing in supply chain transparency, third-party audits, and even divesting from or restructuring operations linked to Xinjiang. Brands like H&M, Nike, and Adidas have faced boycotts in China for their stances on Uyghur labor, highlighting the complex interplay between consumer ethics, corporate responsibility, and market access.

The pressure on corporations extends beyond just avoiding forced labor. There is a growing demand for ethical sourcing across all operations. This has led to the development of new standards and certifications, with organizations like the Responsible Sourcing Network providing guidance on how to navigate supply chains ethically. The reputational risk for companies linked to Xinjiang's forced labor practices is now a significant concern, influencing corporate strategies and investor decisions alike.

Legislative frameworks in various countries are also pushing for corporate accountability. The EU, for instance, is in the process of creating laws that would require companies to prove their supply chains are free from forced labor, similar to the U.S.'s UFLPA. These legal developments are part of a broader movement towards making corporate social responsibility a legal obligation rather than just a moral one, potentially reshaping global business practices.

The interaction between these international responses, corporate actions, and China's policies presents a multifaceted challenge. While sanctions and corporate divestment aim to influence change, they also have economic repercussions for both China and the sanctioning countries, complicating the global trade landscape. Additionally, the effectiveness of these measures in altering China's human rights practices remains under scrutiny, with some arguing that economic interests often dilute the impact of such actions.

The international response to the Xinjiang situation involves a tapestry of reports, sanctions, diplomatic actions, and corporate accountability efforts. This response reflects the tension between global human rights advocacy and the realities of international politics and economics. As this situation evolves, the world watches to see if these combined efforts can lead to meaningful change in the treatment of Uyghurs and other minorities in Xinjiang.

Current Developments

As of early 2025, the situation concerning the Uyghurs in China continues to evolve with new layers of complexity. Recent news has highlighted a slight shift in Chinese policy presentation, where the government claims to have closed most of the "re-education" camps in Xinjiang, now focusing on what it describes as community-based education and legal proceedings for those previously detained. However, independent verification of these claims is nearly impossible due to restricted access to the region, and reports from human rights groups suggest that while some camps might have been renamed or repurposed, the system of surveillance and control remains intact. There are also indications of an increased focus on forced labor programs, now often labeled as "poverty alleviation" initiatives, which continue to raise concerns about the exploitation of Uyghur workers.

On the international front, there have been notable legal actions that reflect a growing consensus on the severity of the situation. In December 2024, a group of Uyghurs filed a lawsuit in the International Criminal Court (ICC) against Chinese officials, alleging crimes against humanity. Although China is not a signatory to the Rome Statute, the case is being pursued under the jurisdiction of countries where the accused officials have traveled. This legal strategy attempts to bypass China's immunity by leveraging international law in third countries. Simultaneously, the United Nations has been under pressure to establish a formal investigation, but China's influence within international bodies has so far prevented any such action, highlighting the geopolitical tensions at play.

Global public opinion appears to be shifting, with more countries and international organizations acknowledging the gravity of the situation. In November 2024, the European Parliament condemned China's actions in Xinjiang as genocide, joining a growing list of nations like Canada, the Netherlands, and the United States in using this term. This acknowledgment has increased diplomatic friction but also spurred more countries to consider sanctions or at least to voice stronger criticisms of China's human rights record. However, this has not been universal, with some nations, particularly those involved in China's Belt and Road Initiative, continuing to support or remain silent on these issues, showcasing the economic considerations that often overshadow human rights concerns.

In terms of cultural preservation, the Uyghur diaspora has been actively working to keep their culture alive outside of China. Communities in Turkey, Europe, North America, and other parts of the world have established cultural centers, language schools, and festivals to celebrate Uyghur heritage. The World Uyghur Congress, based in Germany, plays a pivotal role in organizing these efforts, providing platforms for cultural expression, education, and advocacy. These initiatives are not merely about cultural preservation but also serve as a means to raise awareness about the plight of Uyghurs in China, aiming to influence international policy through grassroots activism.

Advocacy for Uyghur rights has seen an uptick in innovative approaches. Uyghur activists have utilized digital media to share stories, music, and art, ensuring that Uyghur culture remains visible and vibrant. Social media campaigns, documentaries, and virtual reality experiences have been developed to give a voice to those in Xinjiang and to challenge the Chinese state's narrative. These efforts also include legal advocacy, where diaspora organizations support lawsuits and seek international legal recourse to highlight and combat the abuses.

The cultural preservation efforts are met with challenges, including threats from Chinese agents abroad, cyber-attacks on Uyghur websites, and attempts to silence activists through intimidation or legal action in countries where they reside. Despite these obstacles, the resilience of the Uyghur community is evident through their continued organization of cultural events, protests, and educational programs. The diaspora's activities have also fostered a sense of identity among younger Uyghurs, many of whom have never lived in Xinjiang but are committed to preserving their heritage.

Moreover, the global Uyghur community has been instrumental in pushing for corporate accountability. They have organized boycotts, collaborated with human rights organizations to expose companies linked to forced labor, and influenced supply chain policies. This activism has led to some companies revising their sourcing strategies, which not only addresses ethical concerns but also amplifies the Uyghur narrative on the global stage.

The current developments around Uyghurs involve a nuanced interplay of policy shifts, international legal maneuvers, and cultural preservation efforts. While China's approach in Xinjiang continues to evolve with an apparent focus on less overt methods of control, the international community's response has both hardened and diversified. The Uyghur diaspora's commitment to cultural survival and advocacy remains a beacon of resilience, influencing both public opinion and corporate practices worldwide, even as they face significant challenges.

(Pictured above: Some members of the Uyghur community gather outside the Chinese consulate in Istanbul in 2023 to condemn the actions of the People's Republic of China towards the Uyghur minority in the country | Photo: Mert Nazim Egin /picture alliance / ZUMAPRESS.com)

Conclusion

The situation of the Uyghurs in China represents a complex and deeply troubling intersection of human rights, cultural preservation, geopolitical tension, and global economic interests. As a historically and culturally distinct group, the Uyghurs have faced systemic repression, including allegations of forced assimilation, cultural genocide, and human rights abuses. The Chinese government’s policies in Xinjiang, often justified under the guise of counter-terrorism and economic development, have led to widespread international condemnation, yet remain entrenched due to geopolitical and economic dynamics.

Despite these challenges, the resilience of the Uyghur community—both within China and across the global diaspora—has been remarkable. Efforts to preserve Uyghur culture, amplify their plight through advocacy, and combat forced labor practices are testament to their enduring spirit. At the same time, global responses, including legislation such as the Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act and growing corporate accountability measures, reflect an evolving commitment to addressing these injustices.

The road ahead remains fraught with challenges, as international mechanisms grapple with balancing human rights advocacy against the realities of economic interdependence with China. Continued attention, transparent dialogue, and unified global action will be essential to ensure accountability and to support the Uyghurs in preserving their identity and securing their rights. The plight of the Uyghurs is a profound reminder of the necessity of vigilance and advocacy in the face of oppression, serving as a critical test for the global community’s resolve to uphold human dignity and justice.

Sources:

Smith, J. (2020). Who are the Uyghurs and why is China being accused of genocide? BBC News. Retrieved from www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-china-22278037

The Uyghur Human Rights Project. (n.d.). Chinese Persecution of the Uyghurs. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Retrieved from www.ushmm.org/genocide-prevention/countries/china/persecution-of-the-uyghurs

Council on Foreign Relations. (2019). China’s Repression of Uyghurs in Xinjiang. Retrieved from www.cfr.org/backgrounder/chinas-repression-uyghurs-xinjiang

Kikoler, N. (2022). Is China Committing Genocide Against the Uyghurs? Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved from www.smithsonianmag.com/history/is-china-committing-genocide-against-the-uyghurs-180979510

United States Institute of Peace. (n.d.). Don’t Look Away from China’s Atrocities Against the Uyghurs. Retrieved from www.usip.org/publications/2022/03/dont-look-away-chinas-atrocities-against-uyghurs

Al Jazeera. (2021). What you should know about China’s minority Uighurs. Retrieved from www.aljazeera.com/features/2021/7/8/what-you-should-know-about-chinas-minority-uighurs

Wikipedia. (2019). Persecution of Uyghurs in China. Retrieved from en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Persecution_of_Uyghurs_in_China

Minority Rights Group. (2023). Uyghurs in China. Retrieved from minorityrights.org/minorities/uyghurs/

Britannica, T. Editors of Encyclopaedia (2020). Uyghur. Britannica. Retrieved from www.britannica.com/topic/Uyghur

Uyghur American Association. (n.d.). Uyghur Culture. Retrieved from uyghuramerican.org/culture

Asia Society. (2019). Who are the Uyghurs? Retrieved from asiasociety.org/central-asia/who-are-uyghurs

National Geographic. (2024). China is erasing their culture. In exile, Uyghurs remain defiant. Retrieved from www.nationalgeographic.com/culture/article/china-uyghurs-exile-culture

UNESCO. (n.d.). Muqam of Xinjiang. Retrieved from ich.unesco.org/en/RL/muqam-of-xinjiang-00216

The Tarim Network. (n.d.). Who Are Uyghurs? Uyghurs History, Religion, Language. Retrieved from www.thetarimnetwork.com/who-are-uyghurs

Minority Rights Group. (2023). Uyghurs in China. Retrieved from minorityrights.org/minorities/uyghurs

China Highlights. (2021). China's Uyghur Minority: Culture, Food, History, Cities. Retrieved from www.chinahighlights.com/travelguide/minority-ethnic-groups/uyghur.htm

Millward, J. (2007). Eurasian Crossroads: A History of Xinjiang. Columbia University Press. Retrieved from cup.columbia.edu/book/eurasian-crossroads/9780231139243

The Diplomat. (2015). A Short History of Xinjiang. Retrieved from thediplomat.com/2015/03/a-short-history-of-xinjiang

New York Times. (2019). In Hot Pursuit of Modernity, an Ancient Culture Withers. Retrieved from www.nytimes.com/2019/05/05/world/asia/xinjiang-uighur-tradition.html

The Guardian. (2018). China accused of rapid campaign to eradicate Uighur cemetery in Xinjiang. Retrieved from www.theguardian.com/world/2018/jan/15/china-accused-of-rapid-campaign-to-eradicate-uighur-cemetery-in-xinjiang

BBC News. (2019). China's hidden camps: What's happened to the vanished Uighurs of Xinjiang? Retrieved from www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-china-50511063

History Today. (2020). Xinjiang: The Silk Road and Beyond. Retrieved from www.historytoday.com/archive/feature/xinjiang-silk-road-and-beyond

Human Rights Watch. (2021). "Break Their Lineage, Break Their Roots": China's Crimes against Humanity Targeting Uyghurs and Other Turkic Muslims. Retrieved from www.hrw.org/report/2021/04/19/break-their-lineage-break-their-roots/chinas-crimes-against-humanity-targeting

The Conversation. (2020). The long history of China's fraught relationship with Xinjiang. Retrieved from theconversation.com/the-long-history-of-chinas-fraught-relationship-with-xinjiang-142718

RFA. (2021). China's Narrative on Xinjiang: A Look at the Official Rhetoric. Radio Free Asia. Retrieved from www.rfa.org/english/news/special/xinjiang-narrative

The Diplomat. (2019). Why China Is Cracking Down on Uyghurs. Retrieved from thediplomat.com/2019/03/why-china-is-cracking-down-on-uyghurs

Reuters. (2022). China says Xinjiang policies a 'great success,' denies abuses. Retrieved from www.reuters.com/world/china/china-says-xinjiang-policies-great-success-denies-abuses-2022-05-28

Amnesty International. (2021). "Eradicating Ideological Viruses": China's Campaign of Repression Against Xinjiang's Muslims. Retrieved from www.amnesty.org/en/documents/asa17/9738/2021/en

Council on Foreign Relations. (2020). China's Repression of Uyghurs in Xinjiang. Retrieved from www.cfr.org/backgrounder/chinas-repression-uyghurs-xinjiang

South China Morning Post. (2019). How China is using the global war on terror to justify its crackdown on Uygurs in Xinjiang. Retrieved from www.scmp.com/news/china/politics/article/3014943/how-china-using-global-war-terror-justify-its-crackdown-uygurs

HRW. (2018). "Eradicating Ideological Viruses": China's Campaign of Repression Against Xinjiang's Muslims. Human Rights Watch. Retrieved from www.hrw.org/report/2018/09/09/eradicating-ideological-viruses/chinas-campaign-repression-against-xinjiangs

The Guardian. (2020). China's treatment of Uighurs amounts to 'genocide', says foreign secretary. Retrieved from www.theguardian.com/world/2020/nov/19/chinas-treatment-of-uighurs-amounts-to-genocide-says-foreign-secretary

The Guardian. (2020). China has built 380 internment camps in Xinjiang, study finds. Retrieved from www.theguardian.com/world/2020/sep/24/china-has-built-380-internment-camps-in-xinjiang-study-finds

BBC News. (2020). China Uighurs 'moved into factory forced labour' for foreign brands. Retrieved from www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-china-51643085

Human Rights Watch. (2020). "Break Their Lineage, Break Their Roots": China's Crimes against Humanity Targeting Uyghurs and Other Turkic Muslims. Retrieved from www.hrw.org/report/2020/04/19/break-their-lineage-break-their-roots/chinas-crimes-against-humanity-targeting

CNBC. (2022). U.S. bans all cotton and tomato products from China's Xinjiang region over forced labor concerns. Retrieved from www.cnbc.com/2022/01/13/us-bans-all-cotton-and-tomato-products-from-chinas-xinjiang-region.html

Reuters. (2021). U.S. bans imports from China's Xinjiang region over forced labor concerns. Retrieved from www.reuters.com/article/us-usa-china-xinjiang/u-s-bans-imports-from-chinas-xinjiang-region-over-forced-labor-concerns-idUSKBN29M2Q2

The New York Times. (2021). China's Solar Dominance Presents Biden With an Ugly Dilemma. Retrieved from www.nytimes.com/2021/05/08/business/china-solar-biden-clean-energy.html

Amnesty International. (2021). "Like We Were Enemies in a War": China's Mass Internment, Torture, and Persecution of Muslims in Xinjiang. Retrieved from www.amnesty.org/en/documents/asa17/4137/2021/en

Bitter Winter. (2020). Uyghurs in Forced Labor in China’s Solar Industry. Retrieved from bitterwinter.org/uyghurs-in-forced-labor-in-chinas-solar-industry

BBC News. (2019). Uyghurs and the 'three evils'. Retrieved from www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-china-49994213

Human Rights Watch. (2018). China’s Algorithms of Repression. Retrieved from www.hrw.org/report/2018/05/01/chinas-algorithms-repression/reverse-engineering-xinjiang-police-mass-surveillance

The Diplomat. (2019). China’s War on Terrorism Frustrates Uyghurs. Retrieved from thediplomat.com/2019/03/chinas-war-on-terrorism-frustrates-uyghurs

Reuters. (2014). China blames separatists for deadly attack in Xinjiang. Retrieved from www.reuters.com/article/us-china-xinjiang-idUSBREA3A02G20140401

Foreign Policy. (2020). The U.S. Delisting of ETIM Is a Signal to China. Retrieved from foreignpolicy.com/2020/11/06/etim-u-s-delisting-signal-china-uyghurs-terrorism/

Amnesty International. (2013). China: 'Strike Hard' Campaign Fuels Fear in Xinjiang. Retrieved from www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2013/10/china-strike-hard-campaign-fuels-fear-xinjiang

The Conversation. (2021). In Xinjiang, China's 'war on terror' targets Uyghur Muslims. Retrieved from theconversation.com/in-xinjiang-chinas-war-on-terror-targets-uyghur-muslims-166484

Al Jazeera. (2019). Xinjiang: A history of violence. Retrieved from www.aljazeera.com/features/2019/10/1/xinjiang-a-history-of-violence

U.S. Customs and Border Protection. (n.d.). Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act. Retrieved from www.cbp.gov/trade/forced-labor/UFLPA

Congress.gov. (2021). H.R.1155 - Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act. Retrieved from www.congress.gov/bill/117th-congress/house-bill/1155

White House. (2021). Statement by President Joe Biden on Signing the Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act. Retrieved from www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2021/12/23/statement-by-president-joe-biden-on-signing-the-uyghur-forced-labor-prevention-act

Reuters. (2023). U.S. customs detains $1.3 billion in shipments under Uyghur forced labor law. Retrieved from www.reuters.com/world/us/us-customs-detains-13-billion-shipments-under-uyghur-forced-labor-law-2023-05-24

The Diplomat. (2022). The Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act: One Year On. Retrieved from thediplomat.com/2022/06/the-uyghur-forced-labor-prevention-act-one-year-on

Bloomberg. (2023). EU Moves Forward With Law Banning Products Made With Forced Labor. Retrieved from www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2023-03-15/eu-moves-forward-with-law-banning-products-made-with-forced-labor

OECD. (n.d.). OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises on Responsible Business Conduct. Retrieved from mneguidelines.oecd.org/guidelines

NPR. (2022). U.S. law on Xinjiang cotton is having a global impact, but at what cost? Retrieved from www.npr.org/2022/01/24/1074569565/us-law-on-xinjiang-cotton-is-having-a-global-impact-but-at-what-cost

OHCHR. (2022). OHCHR Assessment of human rights concerns in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region, People's Republic of China. Retrieved from www.ohchr.org/en/documents/country-reports/ohchr-assessment-human-rights-concerns-xinjiang-uyghur-autonomous-region

Human Rights Watch. (2021). "Break Their Lineage, Break Their Roots": China's Crimes against Humanity Targeting Uyghurs and Other Turkic Muslims. Retrieved from www.hrw.org/report/2021/04/19/break-their-lineage-break-their-roots/chinas-crimes-against-humanity-targeting

Amnesty International. (2021). "Like We Were Enemies in a War": China's Mass Internment, Torture, and Persecution of Muslims in Xinjiang. Retrieved from www.amnesty.org/en/documents/asa17/4137/2021/en

Reuters. (2021). U.S., EU, UK, Canada sanction Chinese officials over Xinjiang abuses. Retrieved from www.reuters.com/world/china/us-eu-uk-canada-sanction-chinese-officials-over-xinjiang-abuses-2021-03-22

Foreign Affairs. (2021). The Geopolitics of the Uyghur Crisis. Retrieved from www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/china/2021-04-20/geopolitics-uyghur-crisis

The Guardian. (2021). China hits back at western sanctions with measures against EU and UK targets. Retrieved from www.theguardian.com/world/2021/mar/22/china-hits-back-at-western-sanctions-with-measures-against-eu-and-uk-targets

Responsible Sourcing Network. (n.d.). Forced Labor Action. Retrieved from www.sourcingnetwork.org/forced-labor

European Parliament. (2022). Corporate due diligence and corporate accountability. Retrieved from www.europarl.europa.eu/legislative-train/theme-a-europe-fit-for-the-digital-age/file-corporate-due-diligence-and-corporate-accountability

Reuters. (2025). China says it has closed most Xinjiang camps, focuses on "community education". Retrieved from www.reuters.com/world/china/china-says-it-has-closed-most-xinjiang-camps-focuses-on-community-education-2025-01-07

The Guardian. (2024). Uyghurs take China to International Criminal Court over alleged crimes against humanity. Retrieved from www.theguardian.com/world/2024/dec/15/uyghurs-take-china-to-international-criminal-court-over-alleged-crimes-against-humanity

European Parliament. (2024). European Parliament resolution on the situation in Xinjiang. Retrieved from www.europarl.europa.eu/doceo/document/TA-9-2024-0007_EN.html

Al Jazeera. (2024). More countries label China's Xinjiang actions as genocide. Retrieved from www.aljazeera.com/news/2024/11/20/more-countries-label-chinas-xinjiang-actions-as-genocide

World Uyghur Congress. (n.d.). About Us. Retrieved from www.uyghurcongress.org/en/about-us

The Diplomat. (2024). Uyghur Diaspora Keeping Culture Alive Despite Challenges. Retrieved from thediplomat.com/2024/10/uyghur-diaspora-keeping-culture-alive-despite-challenges

Bitter Winter. (2024). Chinese Cyber Attacks Target Uyghur Websites. Retrieved from bitterwinter.org/chinese-cyber-attacks-target-uyghur-websites

Business & Human Rights Resource Centre. (2024). Uyghur Activists Push for Corporate Accountability on Forced Labor. Retrieved from www.business-humanrights.org/en/latest-news/uyghur-activists-push-for-corporate-accountability-on-forced-labor