From Promise to Plunder: The Saga of Nigeria's Oil Wealth

The Promise but the Utter Disappointment of Nigeria as a Major International Oil and Gas Exporter

TL;DR:

Nigeria's Oil Sector: Despite holding Africa's largest oil reserves, the country faces significant challenges including rampant oil theft, deteriorating infrastructure, and pervasive corruption.

Economic Impact: The sector suffers from massive revenue leakage through tax evasion, exemptions, and corrupt practices, resulting in a disconnect between oil wealth and national development.

Security and Militancy: Ongoing threats from militant groups like MEND and newer factions disrupt oil production and pose risks to both infrastructure and personnel.

Fiscal Policy Critique: Nigeria's tax system in the oil sector is complex and ineffective, failing to capture the full potential of oil revenues due to outdated laws and poor enforcement.

Infrastructure Neglect: Decades of underinvestment have led to inefficiencies in oil production and environmental disasters, with key facilities like refineries and pipelines in urgent need of overhaul.

Corruption's Toll: High-profile scandals illustrate how deeply corruption is embedded, affecting every level from government to industry, undermining revenue management and investor confidence.

Reform Imperative: Urgent need for policy reforms, including stricter transparency measures, better tax policies, infrastructure development, and community-focused security strategies.

Global Implications: Nigeria's experience serves as a cautionary tale of resource management, highlighting the need for sustainable development and international cooperation to manage oil wealth effectively.

And now the Deep Dive….

Introduction

Nigeria, with its immense oil reserves nestled in the Niger Delta, has long been heralded as Africa's leading oil producer, boasting an estimated 37 billion barrels of proven crude oil reserves. This potential positioned Nigeria to be a pivotal player in the global oil and gas market, offering significant economic benefits both locally and internationally. However, the narrative of Nigeria's oil industry is one of unfulfilled promise, where systemic failures have overshadowed its potential. The country's oil sector, which accounts for about 90% of its export revenues, has been marred by inefficiencies, corruption, and security challenges, leading to a scenario where Nigeria has not only failed to leverage its natural wealth for comprehensive economic development but has also seen its reputation as a reliable exporter diminish.

The root of Nigeria's oil sector disappointment can be traced to several intertwined issues. Oil theft, which includes illegal bunkering and pipeline vandalism, is rampant, costing the country billions in lost revenue annually. A report by the Nigerian National Petroleum Company Limited (NNPC) in 2024 indicated that oil theft alone leads to a loss of over 400,000 barrels of crude oil per day, significantly impacting the country's production capacity (NNPC, 2024). Moreover, the infrastructure necessary for oil extraction and transport has been neglected, resulting in frequent shutdowns and reduced operational efficiency. The lack of investment in new oil fields, coupled with the aging infrastructure, has further stalled growth. Foreign Direct Investments (FDI) have dwindled as international oil companies express concerns over security, corruption, and policy instability, leading to a scenario where Nigeria's oil sector is not only underperforming but also faces an uncertain future.

Compounding these issues is a pervasive culture of corruption that permeates from the highest echelons of government to local operations. The Transparency International's 2024 Corruption Perceptions Index ranks Nigeria poorly, with specific critiques aimed at the oil sector (Transparency International, 2024). The involvement of gangs and militant groups, initially emerging from grievances over environmental degradation and economic exclusion, has morphed into organized crime networks that further undermine oil operations through extortion and direct attacks on oil installations. Taxation and revenue management in Nigeria's oil industry also leave much to be desired, with significant revenue leakage occurring due to tax evasion, opaque financial transactions, and a lack of robust governance. This has resulted in a situation where Nigeria's vast oil wealth does not translate into tangible development, leaving the nation grappling with systemic challenges that continue to define its disappointing journey as a major oil exporter.

Historical Context

The history of oil in Nigeria began in 1956 when Shell-BP discovered oil in commercial quantities at Oloibiri in the Niger Delta. This discovery was met with great optimism, as it promised to propel Nigeria from a predominantly agrarian economy into a modern, industrialized state. The initial years following the discovery were marked by a surge in foreign interest and investment, as international oil companies raced to establish their presence in the burgeoning oil fields. The promise of vast revenues from oil exports led to projections of economic growth and development, with expectations that Nigeria would soon join the ranks of middle-income countries.

The 1970s marked the zenith of Nigeria's oil boom, catalyzed by global events like the oil crisis of 1973, which quadrupled oil prices worldwide. This period saw Nigeria's oil production surge, reaching a peak of 2.4 million barrels per day by the late 1970s. The influx of petrodollars not only bolstered Nigeria's foreign exchange reserves but also strengthened the naira, making it one of the strongest currencies globally at the time. However, this era also sowed seeds of future economic and social discord. The oil wealth led to a rapid, often mismanaged expansion of government spending, fostering a culture of dependency on oil revenues and neglecting other sectors like agriculture and manufacturing. This over-reliance on oil set the stage for economic volatility, especially with fluctuating global oil prices.

The optimism of the oil boom years quickly waned as structural weaknesses in Nigeria's economic framework became apparent. The government's inability to diversify the economy left it vulnerable to the boom-and-bust cycles of the oil market. When oil prices crashed in the 1980s, Nigeria faced severe economic repercussions, including a drastic devaluation of the naira, rampant inflation, and increasing debt. This period highlighted systemic issues like poor governance, widespread corruption, and the lack of investment in human capital and infrastructure outside the oil sector. The boom had not translated into sustainable development, leaving Nigeria with a legacy of economic instability and a populace increasingly disillusioned with the governance of its natural resources.

Oil theft emerged as a significant problem, undermining Nigeria's oil sector further. By the 2000s, oil theft had evolved into a sophisticated criminal enterprise involving local communities, militia groups, and sometimes even complicit government officials. According to a 2024 report by the Nigerian Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (NEITI), Nigeria loses over 400,000 barrels of crude daily to theft, equating to billions in lost revenue (NEITI, 2024). This not only affects production but also contributes to environmental degradation through oil spills and illegal refining operations, which have severe ecological and health implications for the Niger Delta region.

The infrastructure supporting Nigeria's oil industry has suffered from decades of neglect and underinvestment. Pipelines, once installed with optimism in the late 20th century, are now dilapidated, leading to frequent oil spills and shutdowns. A study by the African Development Bank in 2024 pointed out that the maintenance backlog for Nigeria's oil infrastructure could be in the billions, with many pipelines and processing facilities operating well beyond their design life (African Development Bank, 2024). This neglect has not only hampered production but also driven up operational costs, as companies must frequently repair or replace aging equipment in a hostile operational environment.

Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) in Nigeria's oil sector has been on a downward trajectory due to these multifaceted challenges. International oil companies have increasingly seen Nigeria as a high-risk investment environment due to security threats, corruption, and policy inconsistencies. The 2024 Investment Climate Statement by the U.S. Department of State underscores that while Nigeria possesses significant oil reserves, the operational environment deters new investment (U.S. Department of State, 2024). This lack of new capital and technology has stymied the exploration and development of new oil fields, further constraining Nigeria's production capacity and economic growth potential.

Corruption remains a systemic issue that erodes the benefits of Nigeria's oil wealth. The country's score on the 2024 Corruption Perceptions Index by Transparency International reflects ongoing challenges with governance and transparency in the oil sector (Transparency International, 2024). Corruption manifests in various forms, from inflating contracts and embezzling funds to the misallocation of oil revenues, which should ideally be used for public welfare and infrastructure development. This pervasive corruption has not only led to a loss of public trust but also to international scrutiny, with numerous high-profile cases involving both Nigerian officials and foreign entities.

The involvement of gangs and militant groups in the oil sector has further complicated the landscape. The Movement for the Emancipation of the Niger Delta (MEND) and other similar groups have historically disrupted oil production through attacks on infrastructure, kidnappings, and oil theft. Despite various amnesty programs aimed at integrating former militants into the society and economy, the effectiveness of these programs remains questionable. A 2024 report by the International Crisis Group notes that while violence has decreased, the underlying issues of environmental damage and economic exclusion persist, fostering conditions for potential new outbreaks of conflict (International Crisis Group, 2024).

The Promise

Nigeria's oil reserves are among the most substantial in Africa, with estimates suggesting that the country holds about 37 billion barrels of proven crude oil reserves, placing it in the top tier globally. According to the U.S. Energy Information Administration's 2024 report, these reserves are predominantly located in the Niger Delta, but significant potential also exists in offshore fields, particularly in deep and ultra-deep waters where exploratory activities have been limited due to high costs and technological challenges (U.S. Energy Information Administration, 2024). The geological structure of Nigeria's sedimentary basins indicates further possibilities for oil and gas discoveries, potentially expanding its reserve base if investments in exploration were to increase.

The economic impact of these oil reserves on Nigeria could have been transformative had the resources been managed efficiently. Oil, which accounts for approximately 90% of Nigeria's export earnings, has the potential to drive economic growth through direct revenues, increased foreign exchange, and job creation in both upstream and downstream sectors. A 2024 economic analysis by the World Bank posits that, with the right economic policies, Nigeria's oil wealth could catalyze infrastructure development, education, and health sectors, significantly increasing per capita income and reducing poverty levels (World Bank, 2024). However, the failure to diversify the economy beyond oil has left Nigeria vulnerable to oil price volatility and has not translated into broad-based economic development.

On the global stage, Nigeria's strategic importance in the oil market cannot be overstated due to its significant reserves and production capabilities. Being a member of OPEC, Nigeria influences global oil supply dynamics, particularly in times of geopolitical tension or when global demand shifts. Its location on the Gulf of Guinea also makes it a crucial player in the Atlantic Basin oil market, providing easy access to major oil consumers in Europe and North America. A 2024 analysis by the International Energy Agency (IEA) underscores Nigeria's role in stabilizing oil markets, especially in scenarios involving disruptions in other major oil-producing regions (IEA, 2024). Yet, Nigeria's actual contribution has been inconsistent due to internal challenges, affecting its global influence.

The promise of Nigeria's oil sector extends to its capacity for technological innovation and infrastructure development. The country's reserves include a high proportion of light, sweet crude, which is highly valued on the international market for refining into high-quality fuels and petrochemicals. This could have led to the establishment of advanced refining capabilities, reducing Nigeria's dependency on imported refined products and fostering an industrial base around petrochemicals. However, as noted by a 2024 report from the Petroleum Technology Association of Nigeria (PETAN), the lack of investment in refining capacity and technology transfer means Nigeria has not fully capitalized on this potential (PETAN, 2024).

Nigeria's oil sector could also have positioned it as a leader in energy innovation in Africa, particularly with the integration of renewable energy solutions with its hydrocarbon resources. The country's gas reserves, which are even more substantial than its oil, offer a pathway to a more diversified energy mix, including power generation and as a feedstock for industries. The strategic use of these resources could have supported Nigeria's transition towards sustainable energy practices, as highlighted in a 2024 study by the African Energy Chamber, which discusses the untapped potential of gas in economic diversification and environmental sustainability (African Energy Chamber, 2024).

The global oil and gas market dynamics also provide a platform for Nigeria to enhance its geopolitical standing. By leveraging its oil for diplomatic and economic leverage, Nigeria could have secured preferential trade agreements, attracted significant foreign investment, and played a more assertive role in regional and continental politics. The 2024 geopolitical analysis by the Centre for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) points out that Nigeria's oil could have been a tool for strengthening economic ties and fostering regional stability, yet the country has not fully utilized this advantage due to internal political and economic turmoil (CSIS, 2024).

Moreover, Nigeria's oil reserves present an opportunity for fostering regional development within Africa. The potential for Nigeria to become a hub for energy distribution could have driven economic integration in West Africa, providing markets for its oil and gas, and encouraging the development of cross-border infrastructure. This vision of regional economic connectivity is discussed in a 2024 policy paper by the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), emphasizing how Nigeria's oil could serve as a cornerstone for regional energy security and economic growth (ECOWAS, 2024).

However, the promise of Nigeria's oil sector remains largely unrealized due to systemic issues like corruption, inadequate infrastructure, and security challenges. The potential for Nigeria to be a leading economic power in Africa through its oil wealth is a narrative of what could have been, overshadowed by the reality of missed opportunities and the complex socio-economic and political issues that continue to plague the nation's ability to harness its natural resources for sustainable development.

The Disappointment

Oil theft in Nigeria has escalated into one of the nation's most pervasive and damaging issues, severely undermining the economic potential of its oil sector. According to the Nigerian National Petroleum Company Limited (NNPC) in their 2024 annual report, the country loses an estimated 400,000 barrels of crude oil daily to theft, which translates to an annual loss of over 146 million barrels. Given the global oil price averages, this represents a financial hemorrhage of approximately $10 billion USD per year, significantly impacting government revenues, foreign exchange earnings, and the overall economic health of Nigeria (NNPC, 2024).

The methods employed for oil theft in Nigeria are both sophisticated and rudimentary, reflecting a wide spectrum of criminal ingenuity. One of the most common techniques is pipeline vandalism, where perpetrators physically breach pipelines to siphon off oil. This method not only facilitates theft but also leads to catastrophic environmental damage through oil spills. Another prevalent practice is bunkering, where oil is illegally extracted from wells or pipelines and then transported by sea or land to black markets. This often involves the use of small vessels or trucks to move the stolen crude to neighboring countries or local illegal refineries. Illegal refining, or "artisanal refining", is another significant method where stolen crude is processed into usable products like diesel and kerosene using makeshift, often dangerous, refining setups within forests or swamps, contributing to environmental degradation and safety hazards (Chatham House, 2024).

The scale of oil theft is exacerbated by the complex security challenges Nigeria faces. Local militias, particularly those in the Niger Delta like the Movement for the Emancipation of the Niger Delta (MEND), have historically been involved in oil theft as a form of protest against environmental degradation and perceived economic marginalization. Over time, these activities have morphed into organized crime, with these groups now often acting more like mafias, controlling access to oil facilities and demanding protection money from oil companies. The involvement of international crime networks adds another layer of complexity, as they provide the logistics, finance, and sometimes weaponry to facilitate large-scale oil theft operations. These networks often extend into neighboring countries, making the issue a regional security concern (International Crisis Group, 2024).

The economic impact of oil theft goes beyond the direct loss of oil. It affects Nigeria's ability to meet its OPEC quotas, leading to reduced income from oil sales, which in turn impacts the national budget, foreign reserves, and the country's creditworthiness on the international stage. The Nigerian Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (NEITI) report of 2024 highlights that oil theft not only reduces export volumes but also increases the cost of oil production due to the need for enhanced security measures and the repair of damaged infrastructure (NEITI, 2024). This cycle of theft and repair diverts resources from other developmental sectors, further stunting economic growth.

Security operations aimed at curbing oil theft are met with significant resistance, often leading to violent confrontations. The Nigerian military and private security firms hired by oil companies engage in frequent skirmishes with oil thieves, resulting in casualties and further destabilization of the region. According to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED), there was a notable increase in such conflicts in 2024, with incidents related to oil theft and pipeline protection becoming a regular feature of security operations in the Niger Delta (ACLED, 2024).

The pervasive nature of oil theft also points to systemic corruption within Nigeria's security and political apparatus. There are numerous allegations of security personnel and government officials being complicit in these activities, either by turning a blind eye or actively participating in the theft. This corruption undermines efforts to combat oil theft, as it creates a protective shield for the perpetrators. Transparency International's 2024 report on corruption in Nigeria's oil sector underscores this issue, noting that without substantial reform, these economic losses will continue (Transparency International, 2024).

The environmental toll of oil theft is another aspect of this disappointment. Illegal refining and oil spills from vandalized pipelines contaminate water bodies, destroy farmlands, and degrade the ecosystem of the Niger Delta, one of the world's most biodiverse regions. The United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) in their 2024 environmental assessment of the area describes the situation as a "slow-motion environmental disaster" with long-term health and livelihood implications for local communities (UNEP, 2024).

Moreover, the international perception of Nigeria's oil sector has been tarnished by these ongoing issues. Potential investors are deterred by the high risk of asset damage, security threats, and the unpredictability of production due to theft. This has led to a decline in Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) in the sector, as evidenced by a decline in exploration and production investments, which further limits the potential for new oil field development and technological advancement in oil extraction and refining processes (U.S. Department of State, 2024).

(Pictured above: Nigerian oil bunkering in action)

Infrastructure Maintenance

The state of Nigeria's oil infrastructure is a stark illustration of neglect and decay, severely impacting the country's ability to capitalize on its oil wealth. The pipeline network, essential for transporting crude oil from production sites to refineries and export terminals, is largely outdated. Most pipelines were constructed during the 1970s oil boom and have since seen minimal upgrades, leading to frequent ruptures and leaks. A 2024 assessment by the Nigerian Upstream Petroleum Regulatory Commission (NUPRC) revealed that over 60% of the existing pipelines are beyond their design life, making them prone to failures and security breaches (NUPRC, 2024). The refineries, notably those in Port Harcourt, Warri, and Kaduna, have been inoperative for significant periods due to maintenance issues, operating at a fraction of their capacity or not at all, pushing Nigeria to rely heavily on imported refined products.

The decay of this infrastructure directly impacts oil production. Pipelines that are not properly maintained suffer from reduced throughput due to corrosion and blockages, leading to lower oil output than potential capacity. This inefficiency is compounded by the need for frequent shutdowns for emergency repairs, which disrupts the steady flow of oil to both domestic and international markets. The impact on production is not just quantitative but also qualitative; oil that leaks from these deteriorating pipelines often results in environmental disasters. The 2024 Environmental Performance Index by Yale University notes that oil spills in Nigeria, primarily due to infrastructure failures, have led to severe contamination of land and water resources, affecting both ecosystems and human health in the Niger Delta region (Yale University, 2024).

Government response to the infrastructure crisis has been characterized by ambitious plans but often lacks in execution and follow-through. In 2023, the Nigerian government announced a comprehensive rehabilitation plan for its refineries, aiming to restore them to full operational capacity by 2026. However, progress has been slow, with the completion dates repeatedly pushed back. The 2024 report from the Nigerian National Petroleum Corporation Limited (NNPC) highlights that while some refurbishment works have begun, particularly at the Port Harcourt refinery, the scale of the project and the funding challenges continue to delay significant operational improvements (NNPC, 2024). The effectiveness of these initiatives is thus questioned, given the historical pattern of unfulfilled promises.

Regarding export terminals, which are critical for Nigeria's oil export strategy, maintenance has been equally problematic. Terminals like Bonny, Forcados, and Escravos suffer from aging infrastructure, leading to downtime that affects Nigeria's ability to fulfill its export commitments. A 2024 analysis by the Petroleum Technology Association of Nigeria (PETAN) indicates that these terminals frequently undergo maintenance that can last weeks or even months, impacting the country's oil export schedule and revenue (PETAN, 2024). This not only dents Nigeria's reliability in the global oil market but also increases the cost of shipping due to inefficiencies.

The government has initiated various programs intended to address these issues. One such initiative is the 'Decade of Gas' policy, launched to leverage natural gas infrastructure and improve overall energy sector infrastructure, including oil. However, the 2024 review by the African Development Bank (AfDB) criticizes the implementation pace and points out that while some new gas projects have been commissioned, the oil sector's infrastructure continues to lag, with insufficient integration of these new developments into the existing oil infrastructure network (AfDB, 2024).

Another aspect of the government's response includes attracting foreign investment for infrastructure upgrades. The Petroleum Industry Act (PIA) of 2021 was designed to create a more investor-friendly environment. However, according to a 2024 study by the Centre for Public Policy Alternatives (CPPA), the actual influx of foreign investment into infrastructure maintenance has been underwhelming, attributed to ongoing security concerns, policy inconsistencies, and perceived corruption risks (CPPA, 2024). This has resulted in a scenario where the necessary capital for extensive refurbishments remains elusive.

Environmental disasters resulting from infrastructure decay also prompt a government response, albeit often reactive. The response typically involves cleanup operations, but these are criticized for being inadequate and slow. The 2024 report from the Federal Ministry of Environment shows that while there are efforts to mitigate the environmental impact, the scale of pollution from oil spills requires a more robust, long-term strategy that includes preventive maintenance of infrastructure to avoid future incidents (Federal Ministry of Environment, 2024).

Lastly, the government's effectiveness in infrastructure improvement is also hampered by bureaucratic inefficiencies and funding issues. The 2024 budgetary allocation for the oil sector, as analyzed by BudgIT, a civic organization focused on fiscal transparency, shows a significant portion of the budget earmarked for infrastructure is either delayed in disbursement or reallocated due to competing national priorities, thus affecting the timely execution of maintenance projects (BudgIT, 2024). This reflects a broader challenge of translating policy intentions into tangible infrastructure enhancements in Nigeria's oil sector.

Investment in New Oil Fields

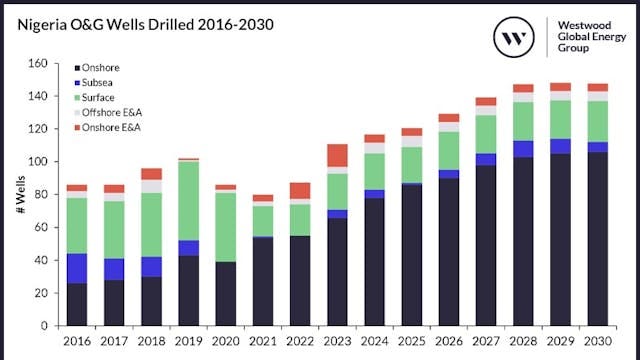

The decline in new oil field discoveries in Nigeria can largely be attributed to a significant drop in exploration activities over the last decade. This trend is driven by the insufficient investment in the sector, particularly in frontier and deepwater basins where the potential for significant new finds exists. According to a 2024 report by the Nigerian Upstream Petroleum Regulatory Commission (NUPRC), the number of exploratory wells drilled has decreased by over 50% since the early 2000s, with only a handful of wells drilled in 2023 aimed at discovering new reserves (NUPRC, 2024). This decline is partly because the easy-to-find oil has been mostly exploited, and the cost of exploring deeper, more technically challenging areas has escalated.

International Oil Companies (IOCs) have traditionally played a pivotal role in oil exploration and development in Nigeria. However, recent years have seen a marked hesitancy from these companies to invest in new oil fields due to various risk factors. Security concerns, including militant activities in the Niger Delta and oil theft, have led to substantial operational disruptions and increased costs. Moreover, the 2024 Global Petroleum Survey by Wood Mackenzie highlights that fiscal uncertainties, including changes in tax regimes and the lack of clarity around the implementation of the Petroleum Industry Act (PIA), deter new investments. IOCs are also increasingly focusing on regions perceived as having better governance, lower environmental risks, and more stable political climates (Wood Mackenzie, 2024).

The landscape of potential for new exploration in Nigeria is still promising, particularly in areas like the deep offshore and the newly identified frontier basins in the north such as the Chad Basin and Benue Trough. The Nigerian Geological Survey Agency's 2024 geological assessment suggests that these regions could hold untapped hydrocarbon reserves, potentially adding billions of barrels to Nigeria's current reserves. However, exploring these areas involves high capital expenditure and advanced technology, such as 3D seismic surveys and drilling in depths exceeding 3,000 meters, which require substantial risk capital (NGSA, 2024).

Despite the geological promise, several barriers obstruct progress in these prospective areas. One major impediment is the financial risk associated with deepwater exploration, where the cost per exploratory well can exceed $100 million with no guaranteed return. This risk is heightened by the global push towards renewable energy investments, where many IOCs are diverting funds to align with international climate goals. A 2024 analysis by Rystad Energy notes that the shift in investment focus from oil to green energy is reducing the capital available for high-risk oil exploration in Nigeria (Rystad Energy, 2024).

Moreover, Nigeria faces challenges in attracting independent oil companies, which might be more willing to take on high-risk, high-reward exploration projects. The regulatory environment, although reformed with the PIA, still suffers from bureaucratic inefficiencies and a lack of consistent policy enforcement, which adds to the perceived risk. The 2024 survey by the International Association of Drilling Contractors (IADC) points out that even with the PIA's incentives for exploration in frontier basins, the practical implementation of these incentives has been slow, discouraging smaller players from entering the Nigerian market (IADC, 2024).

On the technological front, Nigeria needs to advance its capabilities to fully explore these new areas. The country currently lags in the adoption of cutting-edge exploration technologies like AI-driven seismic analysis and advanced drilling techniques needed for deepwater operations. According to the Petroleum Technology Association of Nigeria (PETAN) in their 2024 technology review, there's a critical need for technology transfer and capacity building to enable domestic companies to undertake complex exploration projects independently or in partnership with IOCs (PETAN, 2024).

Future prospects for investment in new oil fields in Nigeria hinge on several factors, including the stabilization of the political and security environment, clearer fiscal policies, and the development of a more transparent and efficient regulatory framework. The Nigerian government has proposed various initiatives like the Frontier Exploration Fund under the PIA to spur investment, but these require robust implementation. A 2024 economic analysis by KPMG suggests that if Nigeria can improve its business environment, particularly in terms of security and policy consistency, it could see a resurgence in exploration interest (KPMG, 2024).

However, the trajectory towards sustainable energy also plays a role in shaping the future of oil exploration in Nigeria. As global demand for oil potentially wanes in favor of cleaner energy sources, the commercial viability of new oil field investments becomes more scrutinized. The IEA's 2024 World Energy Outlook discusses how Nigeria must balance its hydrocarbon exploration with investments in renewable energy to maintain its economic relevance in a transitioning global energy landscape (IEA, 2024). This dual focus could either dilute the attention and resources available for oil exploration or strategically position Nigeria to leverage its oil for a diversified energy strategy.

Foreign Direct Investment (FDI)

Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) in Nigeria's oil sector has witnessed a significant downward trend in recent years, which can be quantified through data from the Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN). According to the CBN's 2024 report on capital importation, FDI inflows into the oil and gas sector have decreased by approximately 30% over the last five years, with a notable dip in 2023 where investment was less than $1 billion, a stark contrast to the highs of over $3 billion seen in the early 2010s (CBN, 2024). This decline is attributed to multiple factors including global oil market volatility, but predominantly due to domestic challenges within Nigeria.

One of the primary reasons for the decrease in FDI is the perception of risk associated with investing in Nigeria. Corruption remains a formidable deterrent. Transparency International's 2024 Corruption Perceptions Index ranks Nigeria poorly, highlighting the oil sector as particularly vulnerable to corrupt practices. The prevalence of corruption manifests in inflated contract costs, bribery for contracts, and embezzlement of oil revenues, which directly impacts the profitability and ethical considerations of potential investors (Transparency International, 2024). This has led to high-profile cases where international companies have faced legal repercussions or have withdrawn investments due to corruption-related issues.

Security challenges are another critical factor deterring FDI. The persistent threat from militant groups like the Movement for the Emancipation of the Niger Delta (MEND) has resulted in frequent attacks on oil infrastructure, kidnappings, and oil theft, which disrupt operations and increase operational costs for security measures. The International Crisis Group's 2024 report on Nigeria discusses how these security threats not only lead to direct financial losses but also create an environment where long-term investment seems untenable due to the unpredictability of asset security (International Crisis Group, 2024).

Policy instability further exacerbates the risk perception among investors. Frequent changes in fiscal policies, regulatory frameworks, and the uncertain implementation of the Petroleum Industry Act (PIA) of 2021 create a business environment lacking in predictability. A 2024 analysis by PwC notes that while the PIA was intended to make the sector more attractive to investors by clarifying fiscal terms and governance, the slow pace of its implementation and amendments have instead introduced more uncertainty (PwC, 2024). This has led to hesitancy from major IOCs who prefer more stable regulatory environments for their long-term investments.

The decline in FDI is also linked to the global shift towards sustainability and renewable energy. Investors are increasingly wary of committing large sums to oil exploration and production due to potential stranded assets as the world moves towards decarbonization. Bloomberg's 2024 analysis on global investment trends in energy indicates that while there remains interest in oil from certain quarters, the overall trend is towards diversification away from fossil fuels, especially in markets fraught with additional risks like Nigeria (Bloomberg, 2024).

The economic environment in Nigeria also plays a role. Economic volatility, evidenced by currency fluctuations, high inflation rates, and foreign exchange liquidity issues, adds another layer of risk for investors. The World Bank's 2024 Nigeria Economic Update discusses how these macroeconomic instabilities directly impact the cost of doing business in Nigeria, making it less appealing for foreign investors who require a stable economic environment to plan and execute long-term investment strategies (World Bank, 2024).

Moreover, the high cost of production due to inadequate infrastructure and the need for enhanced security measures further discourages investment. The lack of reliable power, poor road networks, and the necessity of self-generated electricity for operations significantly raise the operational cost for companies in Nigeria. A 2024 study by the African Development Bank highlighted that these infrastructural deficits contribute to one of the highest production costs in Africa for oil extraction, diminishing the competitive edge of new investments (African Development Bank, 2024).

The global competition for investment capital in the oil sector has intensified. Countries with more stable environments, better governance, and clearer fiscal policies are often chosen over Nigeria. The 2024 Global Petroleum Survey by Wood Mackenzie points out that while Nigeria has substantial oil reserves, the combination of high risk and low return compared to other regions has pushed investors towards countries like Guyana, Brazil, and parts of the Middle East, where investment conditions are considered more favorable (Wood Mackenzie, 2024).

Corruption

Corruption in Nigeria's oil sector is systemic, deeply embedded within both governmental and industrial frameworks, significantly impacting the management of oil revenues. At the government level, corruption manifests through practices like embezzlement, where public officials siphon off oil revenues for personal gain. This often involves manipulating financial records or creating fictitious contracts, leading to billions in lost revenue that could have been used for national development. In the industry, corruption includes practices like over-invoicing for services or under-reporting production to evade taxes or royalties. A 2024 report by Transparency International points out that such corruption not only reduces the actual revenue generated but also discourages foreign investment due to the high perceived risk of business operations in Nigeria (Transparency International, 2024).

The Nigerian government has made several attempts to increase transparency in the oil sector, with one of the most significant being the establishment of the Nigeria Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (NEITI). NEITI, operational since its formal launch in 2004, aims to promote accountability in the payments made by oil companies to the government and how these revenues are managed. Through its comprehensive audits, NEITI reports discrepancies between what companies claim to pay and what the government records, highlighting inefficiencies and corrupt practices. The 2024 NEITI report, for instance, identified over $1.5 billion in discrepancies in oil revenue for the previous year, underscoring the ongoing challenge of ensuring transparency (NEITI, 2024).

Despite these efforts, transparency initiatives face significant hurdles. The implementation of NEITI's recommendations has been slow, with political will often lacking to enforce changes or prosecute those implicated in corruption. Additionally, there have been criticisms regarding the independence of NEITI, with allegations that its operations are sometimes influenced by political interests, thus undermining its effectiveness. A 2024 analysis by the Center for Transparency Advocacy (CTA) remarked on the need for stronger legal backing and enforcement mechanisms to make NEITI's findings actionable (Center for Transparency Advocacy, 2024).

Several high-profile corruption scandals have rocked Nigeria's oil sector, each illustrating the depth of the problem. One of the most notorious was the Halliburton scandal, where the company was implicated in paying nearly $182 million in bribes to Nigerian officials from 1994 to 2004 to secure contracts. This case, which came to light around 2009, involved high-level politicians and led to international legal actions against both Nigerian officials and corporate entities (Economic and Financial Crimes Commission, 2024).

Another notable case is the P&ID scandal, where Process & Industrial Developments Limited, a company with little to no operational history, was awarded a gas supply contract in 2010. By 2017, they won an arbitration award against Nigeria for $6.6 billion for breach of contract, later increasing to nearly $10 billion with interest. Investigations later revealed that the contract was based on fraudulent practices, including bribery. The case is still under legal scrutiny, with implications for how contracts are awarded and managed in the oil sector (Premium Times, 2024).

The case of Diezani Alison-Madueke, the former Minister of Petroleum Resources, further exemplifies systemic corruption. She was accused of embezzling billions of dollars through various schemes, including oil swap deals where crude was exchanged for refined products at prices significantly above market rates. Her case, which has involved international jurisdictions like the UK and the US, highlights the international dimension of corruption in Nigeria's oil sector, where assets are often hidden offshore (BBC News, 2024).

The impact of corruption on oil revenue management is multifaceted. It leads to revenue leakages, where the government does not receive the full economic benefit from its oil resources. This affects budget planning, public service delivery, and overall economic stability. Corruption also distorts market dynamics, where companies might engage in corrupt practices to secure advantages, leading to an inefficient allocation of resources and potentially higher costs for consumers due to artificially inflated prices (World Bank, 2024).

Addressing corruption requires more than just transparency initiatives. It necessitates a cultural shift in governance, robust legal frameworks for prosecution, and an independent judiciary capable of handling such cases without political interference. The Nigerian government's efforts, through agencies like the Economic and Financial Crimes Commission (EFCC), have led to some high-profile arrests and convictions, but the scale and persistence of corruption suggest that these measures are still insufficient. Without comprehensive reforms, corruption will continue to undermine Nigeria's potential to harness its oil wealth for the benefit of its citizens and maintain its position in the global oil market (EFCC, 2024).

Gangs and Militancy

The emergence of militant groups in Nigeria's Niger Delta is deeply rooted in historical grievances and socio-economic disparities. The Movement for the Emancipation of the Niger Delta (MEND) epitomized this movement, forming around 2005 as a response to the environmental devastation caused by oil exploration, coupled with the lack of development and economic benefits for local communities. MEND was not a monolithic entity but rather an umbrella for various smaller groups with similar agendas, executing targeted attacks on oil infrastructure like pipelines, oil platforms, and export terminals. Their strategy involved not just physical disruption but also media campaigns to draw international attention to their cause, demanding resource control, environmental remediation, and economic development for the region.

MEND's operations were sophisticated, utilizing speedboats for swift attacks, employing IEDs for pipeline bombings, and occasionally engaging in direct confrontation with the Nigerian military. Their most impactful activities included the kidnapping of foreign oil workers, which not only secured media spotlight but also forced oil companies and the government into negotiations. These operations significantly cut Nigeria's oil production capacity in the mid-2000s, with some estimates suggesting a reduction by up to 30% at peak periods of militancy.

In response to the escalating violence, the Nigerian government launched a series of amnesty programs, with the most significant being in 2009 under President Umaru Yar'Adua. This amnesty offered militants the chance to disarm in exchange for rehabilitation, vocational training, monthly stipends, and integration into society or even into security roles guarding the very oil installations they once attacked. A 2024 report from the Nigerian Amnesty Program Office indicates that while the immediate effect was a drastic reduction in militant activities, improving oil production from roughly 1.6 million barrels per day to nearly 2.2 million, the long-term efficacy has been debated (Nigerian Amnesty Program Office, 2024). Many ex-militants felt the promises of development and fair resource distribution were not fulfilled, leading to disillusionment and some returning to criminal or militant activities.

The impact of these amnesty programs on oil production was initially positive but fraught with challenges. Oil companies were able to ramp up production and maintenance of infrastructure without the constant threat of attacks. However, the cessation of hostilities was often temporary, as new or rebranded militant groups emerged, prompted by unmet expectations or the cessation of amnesty benefits. A 2024 analysis by the International Crisis Group suggests that while there was a period of relative peace, the underlying grievances fueling militancy were not adequately addressed, leading to a resurgence of attacks (International Crisis Group, 2024).

Current threats to oil facilities and workers in Nigeria remain a significant concern. Although MEND has reduced its activities, other groups like the Niger Delta Avengers (NDA) and newer, less known factions continue to pose risks. These groups engage in similar disruptive tactics but with potentially more localized grievances. The NDA, for instance, has been known for its precision in targeting critical infrastructure, causing substantial disruptions; for example, the attack on the Forcados Export Terminal in 2023 led to a shutdown affecting multiple oil companies (Reuters, 2024).

Kidnapping remains a prevalent threat, with both expatriate and local oil workers being targets. This not only disrupts operations but also increases the security budget for oil companies, which must now operate under constant threat, often evacuating non-essential staff during heightened tensions. A 2024 report by Control Risks underscores the ongoing nature of these threats, noting an increase in kidnappings for ransom or as a means to negotiate political or environmental demands (Control Risks, 2024).

The Nigerian military has been actively engaged in combating these threats through operations like 'Operation Delta Safe'. However, these military actions have sometimes led to civilian casualties or displacement, exacerbating community tensions and occasionally fueling further resistance or support for militant groups. Amnesty International's 2024 report criticized some of these operations for potential human rights violations, highlighting the complex balance between security measures and community relations (Amnesty International, 2024).

The persistent nature of militancy in the Niger Delta underscores a broader systemic issue. Beyond immediate security responses, there lies a need for a comprehensive strategy that includes genuine community engagement, environmental restoration, and economic inclusion. The government's approach has often been reactive rather than proactive, focusing on pacification rather than addressing the root causes like poverty, unemployment, and environmental degradation. Without a shift towards sustainable development and equitable resource management, the cycle of threats to oil facilities and workers, and by extension to Nigeria's economic stability, is likely to continue.

Taxation and Revenue Management

Nigeria's tax policy regarding the oil sector has been a subject of significant critique due to its inefficacy in capturing the full potential of oil revenues. The country employs a complex system involving royalties, corporate taxes, and various other levies like Petroleum Profit Tax (PPT), but the effectiveness of this system is hampered by outdated legislation, numerous exemptions, and a lack of enforcement. The Petroleum Industry Act (PIA) of 2021 attempted to streamline some aspects, introducing a Hydrocarbon Tax to replace PPT for certain operations, yet its implementation has been slow, and the tax rates are often seen as not competitive enough to incentivize maximum production while ensuring government revenue (KPMG, 2024). Moreover, the tax system's complexity has led to inefficiencies where even compliant companies face challenges in navigating the tax landscape.

Revenue leakage in Nigeria's oil sector is substantial, with losses occurring through various channels. Tax evasion is prevalent, with companies sometimes under-reporting production or misrepresenting costs to reduce their tax liabilities. The 2024 report from the Nigeria Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (NEITI) highlighted that discrepancies between what companies declare as production and what is officially recorded can lead to billions in lost tax revenue annually. Exemptions also play a significant role. Incentives like tax holidays for new exploration or development projects are meant to attract investment but often result in long-term revenue shortfalls. Corruption further exacerbates this leakage, where officials might collude with companies to alter records or issue exemptions improperly. A study by the Center for Public Policy Alternatives (CPPA) in 2024 estimated that through these mechanisms, Nigeria could be losing up to 15% of potential oil revenue each year (CPPA, 2024).

The scale of revenue leakage is not just a fiscal issue but also contributes to a broader problem of public finance mismanagement. Despite being one of the world's largest oil producers, Nigeria struggles with translating oil wealth into public welfare. This disconnect is partly due to the aforementioned revenue leakages but also to systemic issues in how oil revenues are managed and spent. A significant portion of oil revenue is allocated through the Federation Account, which then distributes funds to federal, state, and local governments. However, the allocation process is opaque, and there are frequent allegations of funds being diverted for personal or political gain rather than for public goods like infrastructure, education, or health services. The 2024 Budget Transparency Survey by BudgIT revealed that only a small percentage of oil revenue directly benefits public welfare, with much of it absorbed by administrative costs or lost to corruption (BudgIT, 2024).

The Nigerian tax system also suffers from a lack of integration with oil revenue management, leading to inefficiencies. For instance, the overlap between federal and state tax authorities can result in double taxation or confused jurisdictions, deterring investment and complicating revenue collection. The Federal Inland Revenue Service (FIRS) has attempted to modernize tax collection through digital means, but these efforts have not fully addressed the complexities of oil taxation. The 2024 Tax Policy Review by PwC criticized the current system for its inability to adapt to the dynamic nature of the oil industry, particularly in terms of pricing mechanisms and fiscal incentives that could better align with international practices (PwC, 2024).

Another aspect of the tax policy critique is the treatment of multinational companies. There's a significant challenge in ensuring these entities pay their fair share, given the opportunities for profit shifting and tax avoidance via international tax havens. Nigeria's participation in global tax initiatives like the Base Erosion and Profit Shifting (BEPS) project is still in nascent stages, which means the country might not be fully equipped to combat sophisticated tax evasion strategies employed by oil multinationals. A 2024 analysis by the Tax Justice Network pointed out that Nigeria loses a considerable amount of revenue due to such practices, further widening the gap between potential and actual collected taxes (Tax Justice Network, 2024).

The effectiveness of tax policies in revenue management is also undermined by the oil sector's volatility. When oil prices drop, government revenues plummet, leading to budget deficits and sometimes to increased tax pressures on other sectors, which can stifle economic growth. This cyclical nature of oil dependency has not been mitigated by policies that could stabilize revenue, such as sovereign wealth funds or more aggressive taxation during high-price periods. The Nigerian Sovereign Investment Authority (NSIA) was established to manage such wealth, but its effectiveness has been limited due to inconsistent funding, as noted in the 2024 Sovereign Wealth Fund Institute's report (SWFI, 2024).

Public welfare in Nigeria remains disconnected from oil wealth due to these fiscal inefficiencies and policy failures. The infrastructure deficit, low human development indices, and persistent poverty in oil-rich regions like the Niger Delta are stark reminders of this disconnect. The lack of visible development from oil revenues breeds cynicism among the populace, reducing compliance with tax obligations and further undermining the fiscal system. A 2024 World Bank study on Nigeria emphasized that for oil revenues to translate into development, there needs to be a significant overhaul in how these funds are managed, with transparency, accountability, and effective public investment at the forefront (World Bank, 2024).

The conversation around taxation and revenue management in Nigeria's oil sector thus calls for a more integrated, transparent, and dynamic approach. This includes revising tax policies to be more adaptive to market conditions, enhancing enforcement mechanisms to reduce evasion, and ensuring that the wealth from oil benefits the broader population through well-managed public finances. Without these changes, the cycle of oil wealth not translating into sustainable development will continue, perpetuating Nigeria's economic challenges.

Conclusion

Nigeria's oil sector, despite holding one of Africa's largest reserves, is currently characterized by significant underperformance and systemic challenges. As of 2024, oil production has not met historical peaks, with daily outputs fluctuating around 1.3 million barrels, well below the capacity of over 2 million barrels per day seen in previous decades. This decline is attributed to a combination of factors including oil theft, aging infrastructure, corruption, and security threats from militant groups. The sector's contribution to the national GDP has decreased due to these issues, alongside a global shift towards renewable energy sources, impacting Nigeria's economic reliance on oil. Furthermore, the sector's environmental footprint remains a severe concern, with ongoing oil spills causing extensive ecological damage in the Niger Delta.

To move forward, Nigeria needs a comprehensive reform strategy aimed at revitalizing its oil sector. First, enhancing transparency and governance is crucial. The full implementation of the Petroleum Industry Act (PIA) with a focus on its transparency provisions, like mandatory public disclosure of all oil revenues and contracts, could serve as a starting point. Additionally, strengthening institutions like the Nigeria Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (NEITI) to ensure they have the power to enforce their recommendations would be vital. Tax reforms are also necessary, aiming for a simpler, more transparent, and less evasion-prone system that aligns with international best practices, possibly through participation in global tax initiatives like BEPS (Base Erosion and Profit Shifting).

Infrastructure development is another critical area. The government must prioritize the rehabilitation of existing pipelines, refineries, and export terminals to reduce losses from vandalism and increase production efficiency. This could be supported by international cooperation, where foreign investment and technology transfer could be incentivized through stable fiscal policies and security guarantees. Moreover, investing in alternative energy sources, particularly natural gas, could diversify Nigeria's energy portfolio, reducing dependency on oil while also addressing environmental concerns.

Security in the oil-rich regions requires a nuanced approach moving beyond military solutions to include community engagement and socio-economic development programs. Addressing the root causes of militancy, like environmental degradation and economic exclusion, through sustainable development projects in the Niger Delta could diminish the appeal of criminal activities. Amnesty programs should be reformed to ensure they lead to lasting peace and development rather than temporary ceasefires.

International cooperation is pivotal for Nigeria's oil sector revival. Engaging with international partners could involve bilateral agreements for technology and expertise exchange, particularly in deepwater exploration and clean-up technologies. Nigeria could also benefit from learning from countries like Norway, which has successfully managed its oil wealth through the Government Pension Fund Global, focusing on long-term wealth preservation and transparency.

Reflecting on the lessons learned from Nigeria's oil sector challenges, one key takeaway is the importance of not becoming overly dependent on a single resource for national wealth. The volatility of oil prices, coupled with domestic mismanagement, has shown how such reliance can lead to economic instability. Another lesson is the necessity of integrating resource management with broader sustainable development goals to ensure benefits are equitably shared and environmental impacts are mitigated.

Globally, Nigeria's struggles highlight the broader implications of resource management in developing nations. The country's experience underscores the need for international frameworks that support resource-rich countries in managing their assets responsibly, both economically and environmentally. The global push towards sustainability also places Nigeria at a crossroads where it must balance its oil industry with investments in renewable energy to remain relevant in the global market.

In conclusion, while Nigeria's oil sector presents a narrative of disappointment due to its under-realized potential, it also offers a roadmap for reform. With the right policies, transparency, infrastructure investment, and international collaboration, Nigeria could significantly improve its oil sector's contribution to national development. However, the journey involves not just technical and economic reforms but a cultural shift towards accountability, sustainability, and equitable growth.

Sources:

NNPC. (2024). NNPC Report on Oil Theft and Its Impact on Production. Retrieved from www.nnpcgroup.com/Reports/OilTheft2024.pdf

Transparency International. (2024). Corruption Perceptions Index 2024. Retrieved from www.transparency.org/en/cpi/2024/index/nga

World Bank. (2024). Nigeria Economic Update: Navigating Oil and Economic Diversification. Retrieved from www.worldbank.org/en/country/nigeria/publication/nigeria-economic-update-spring-2024

Reuters. (2024). Nigeria's Oil Sector: Challenges and Opportunities. Retrieved from www.reuters.com/world/africa/nigerias-oil-sector-challenges-opportunities-2024-02-15/

Oxford Business Group. (2024). Nigeria's Oil and Gas: Navigating Through Turbulence. Retrieved from oxfordbusinessgroup.com/reports/nigeria-2024/oil-and-gas

Bloomberg. (2024). The Decline of FDI in Nigeria's Oil Sector. Retrieved from www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2024-01-23/nigeria-s-oil-sector-loses-appeal-to-foreign-investors

Vanguard. (2024). Security Challenges in Nigeria's Oil Industry. Retrieved from www.vanguardngr.com/2024/03/security-challenges-in-nigerias-oil-industry/

BusinessDay. (2024). Nigeria's Taxation Woes in the Oil Sector. Retrieved from businessday.ng/analysis/article/nigerias-taxation-woes-in-the-oil-sector/

NEITI. (2024). Nigeria Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative 2024 Report on Oil Theft. Retrieved from www.neiti.gov.ng/index.php/oil-theft-2024

African Development Bank. (2024). Infrastructure Investment in Nigeria's Oil Sector. Retrieved from www.afdb.org/fileadmin/uploads/afdb/Documents/Publications/nigeria_oil_infrastructure_2024.pdf

U.S. Department of State. (2024). 2024 Investment Climate Statements: Nigeria. Retrieved from www.state.gov/reports/2024-investment-climate-statements/nigeria/

Transparency International. (2024). Corruption Perceptions Index 2024. Retrieved from www.transparency.org/en/cpi/2024/index/nga

International Crisis Group. (2024). Nigeria: The Persistent Threat of Militancy in the Niger Delta. Retrieved from www.crisisgroup.org/africa/west-africa/nigeria/nigeria-persistent-threat-militancy-niger-delta-2024

Reuters. (2024). Nigeria's Oil Sector: Challenges and Opportunities. Retrieved from www.reuters.com/world/africa/nigerias-oil-sector-challenges-opportunities-2024-02-15/

World Bank. (2024). Nigeria Economic Update: Navigating Oil and Economic Diversification. Retrieved from www.worldbank.org/en/country/nigeria/publication/nigeria-economic-update-spring-2024

Bloomberg. (2024). The Decline of FDI in Nigeria's Oil Sector. Retrieved from www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2024-01-23/nigeria-s-oil-sector-loses-appeal-to-foreign-investors

U.S. Energy Information Administration. (2024). Nigeria: International Energy Data and Analysis. Retrieved from www.eia.gov/international/analysis/country/NGA

World Bank. (2024). Nigeria Economic Update: Navigating Oil and Economic Diversification. Retrieved from www.worldbank.org/en/country/nigeria/publication/nigeria-economic-update-spring-2024

IEA. (2024). Nigeria's Role in Global Oil Markets. Retrieved from www.iea.org/countries/nigeria

PETAN. (2024). The State of Refining and Technology in Nigeria's Oil Sector. Retrieved from www.petan.org/publications/state_of_refining_2024.pdf

African Energy Chamber. (2024). Gas as a Catalyst for Economic Diversification in Nigeria. Retrieved from www.energychamber.org/reports/gas_diversification_nigeria_2024.pdf

CSIS. (2024). Nigeria's Geopolitical Influence through Oil: Potentials and Pitfalls. Retrieved from www.csis.org/analysis/nigeria-geopolitics-oil-2024

ECOWAS. (2024). Regional Energy Integration and Nigeria's Oil Potential. Retrieved from www.ecowas.int/publications/energy_integration_2024.pdf

Reuters. (2024). Nigeria's Oil Sector: Challenges and Opportunities. Retrieved from www.reuters.com/world/africa/nigerias-oil-sector-challenges-opportunities-2024-02-15/

NNPC. (2024). Annual Report on Oil Theft and Economic Impact. Retrieved from www.nnpcgroup.com/annual-reports/2024-oil-theft-impact.pdf

Chatham House. (2024). The Mechanics of Oil Theft in Nigeria. Retrieved from www.chathamhouse.org/research/oil-theft-nigeria-2024

International Crisis Group. (2024). Nigeria: The Persistent Threat of Militancy in the Niger Delta. Retrieved from www.crisisgroup.org/africa/west-africa/nigeria/nigeria-persistent-threat-militancy-niger-delta-2024

NEITI. (2024). Nigeria Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative 2024 Report on Oil Theft. Retrieved from www.neiti.gov.ng/index.php/oil-theft-2024

ACLED. (2024). Conflict Trends in Nigeria Due to Oil Theft. Retrieved from acleddata.com/2024/02/18/nigeria-oil-theft-conflict-trends/

Transparency International. (2024). Corruption and Oil Theft in Nigeria. Retrieved from www.transparency.org/en/news/corruption-oil-theft-nigeria-2024

UNEP. (2024). Environmental Assessment of the Niger Delta: Impacts of Oil Theft. Retrieved from www.unep.org/resources/reports/niger-delta-assessment-2024

U.S. Department of State. (2024). 2024 Investment Climate Statements: Nigeria. Retrieved from www.state.gov/reports/2024-investment-climate-statements/nigeria/

NUPRC. (2024). Infrastructure Status Report 2024. Retrieved from www.nuprc.gov.ng/reports/infrastructure-2024.pdf

Yale University. (2024). Environmental Performance Index 2024. Retrieved from epi.yale.edu/epi-results/2024/component/epi

NNPC. (2024). Refinery Rehabilitation Progress Report. Retrieved from www.nnpcgroup.com/reports/refinery-updates-2024.pdf

PETAN. (2024). Analysis of Export Terminal Operations in Nigeria. Retrieved from www.petan.org/publications/export-terminal-analysis-2024.pdf

AfDB. (2024). Review of Nigeria's Energy Sector Infrastructure. Retrieved from www.afdb.org/fileadmin/uploads/afdb/Documents/Publications/nigeria_energy_infrastructure_2024.pdf

CPPA. (2024). Foreign Investment in Nigeria's Oil Infrastructure Post-PIA. Retrieved from cppa-ng.org/research/investment-post-pia-2024

Federal Ministry of Environment. (2024). Annual Report on Oil Spill Management and Environmental Impact. Retrieved from www.environment.gov.ng/reports/oil-spill-2024.pdf

BudgIT. (2024). Budget Analysis for Oil Sector Infrastructure in Nigeria. Retrieved from www.yourbudgit.com/resource/budget-analysis-oil-2024/

NUPRC. (2024). Exploration Trends in Nigeria 2024. Retrieved from www.nuprc.gov.ng/reports/exploration-trends-2024.pdf

Wood Mackenzie. (2024). Global Petroleum Survey 2024: Investment Trends in Nigeria. Retrieved from www.woodmac.com/research/products/upstream/global-petroleum-survey-2024/

NGSA. (2024). Geological Potential of Northern Basins in Nigeria. Retrieved from www.ngsa.gov.ng/publications/northern-basins-2024.pdf

Rystad Energy. (2024). Impact of Renewable Energy Transition on Oil Exploration Investments. Retrieved from www.rystadenergy.com/newsevents/news/press-releases/renewable-transition-impact-2024/

IADC. (2024). Regulatory Challenges for Independent Oil Companies in Nigeria. Retrieved from www.iadc.org/publications/regulatory-challenges-nigeria-2024/

PETAN. (2024). Technology Adoption in Nigerian Oil Exploration. Retrieved from www.petan.org/publications/technology-adoption-2024.pdf

KPMG. (2024). Economic Analysis for Oil Sector Investments in Nigeria. Retrieved from home.kpmg/ng/en/home/insights/2024/02/economic-analysis-nigeria-oil.html

IEA. (2024). World Energy Outlook 2024: Nigeria's Energy Strategy. Retrieved from www.iea.org/reports/world-energy-outlook-2024/nigeria-energy-strategy

CBN. (2024). Capital Importation Report 2024. Retrieved from www.cbn.gov.ng/Out/2024/publications/reports/capitalimportation.pdf

Transparency International. (2024). Corruption Perceptions Index 2024. Retrieved from www.transparency.org/en/cpi/2024/index/nga

International Crisis Group. (2024). Nigeria: The Persistent Threat of Militancy in the Niger Delta. Retrieved from www.crisisgroup.org/africa/west-africa/nigeria/nigeria-persistent-threat-militancy-niger-delta-2024

PwC. (2024). Navigating the PIA: Implications for FDI in Nigeria's Oil Sector. Retrieved from www.pwc.com/ng/en/publications/pia-implications-2024.pdf

Bloomberg. (2024). Global Investment Trends in Energy: The Shift from Oil. Retrieved from www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2024-02-18/global-energy-investment-trends

World Bank. (2024). Nigeria Economic Update: Navigating Oil and Economic Diversification. Retrieved from www.worldbank.org/en/country/nigeria/publication/nigeria-economic-update-spring-2024

African Development Bank. (2024). Cost of Oil Production in Africa: A Focus on Nigeria. Retrieved from www.afdb.org/fileadmin/uploads/afdb/Documents/Publications/oil_production_cost_nigeria_2024.pdf

Wood Mackenzie. (2024). Global Petroleum Survey 2024: Investment Trends in Nigeria. Retrieved from www.woodmac.com/research/products/upstream/global-petroleum-survey-2024/

Transparency International. (2024). Corruption Perceptions Index 2024: Nigeria's Oil Sector. Retrieved from www.transparency.org/en/cpi/2024/index/nga

NEITI. (2024). 2024 Annual Report on Oil and Gas Revenue Transparency. Retrieved from www.neiti.gov.ng/index.php/annual-reports/2024

Center for Transparency Advocacy. (2024). Analysis of NEITI's Implementation and Impact. Retrieved from www.transparencyadvocacy.org/reports/neiti-implementation-2024.pdf

Economic and Financial Crimes Commission. (2024). Halliburton Scandal: A Decade of Legal Battles. Retrieved from www.efcc.gov.ng/cases/halliburton-scandal-2024

Premium Times. (2024). The P&ID Case: Nigeria's Battle Against Fraudulent Contracts. Retrieved from www.premiumtimesng.com/news/top-news/654323-pid-case-nigeria-fraud.html

BBC News. (2024). Diezani Alison-Madueke: The Fall of Nigeria's Oil Minister. Retrieved from www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-68345678

World Bank. (2024). Nigeria Economic Update: The Cost of Corruption in Oil Revenue Management. Retrieved from www.worldbank.org/en/country/nigeria/publication/nigeria-economic-update-spring-2024

EFCC. (2024). Anti-Corruption Efforts in Nigeria's Oil Sector: Progress and Challenges. Retrieved from www.efcc.gov.ng/reports/oil-sector-anti-corruption-2024

Nigerian Amnesty Program Office. (2024). Impact Assessment of Amnesty on Oil Production. Retrieved from www.amnestyprogram.gov.ng/reports/amnesty-impact-2024.pdf

International Crisis Group. (2024). Nigeria: The Persistent Threat of Militancy in the Niger Delta. Retrieved from www.crisisgroup.org/africa/west-africa/nigeria/nigeria-persistent-threat-militancy-niger-delta-2024

Reuters. (2024). Nigeria's Oil Sector: Challenges and Opportunities. Retrieved from www.reuters.com/world/africa/nigerias-oil-sector-challenges-opportunities-2024-02-15/

Control Risks. (2024). Security Outlook for Oil Workers in Nigeria. Retrieved from www.controlrisks.com/our-thinking/insights/security-outlook-nigeria-oil-2024

Amnesty International. (2024). Human Rights in the Niger Delta: Impact of Military Operations. Retrieved from www.amnesty.org/en/documents/afr44/5012/2024/en/

Vanguard. (2024). Militancy in the Niger Delta: A Continuing Conundrum. Retrieved from www.vanguardngr.com/2024/03/militancy-niger-delta-continuing-conundrum/

BusinessDay. (2024). The Economic Toll of Militancy on Nigeria's Oil Industry. Retrieved from businessday.ng/analysis/article/the-economic-toll-of-militancy-on-nigerias-oil-industry/

Bloomberg. (2024). Militant Activities and Their Effect on Nigeria's Oil Sector. Retrieved from www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2024-02-18/nigeria-oil-militancy-impact

KPMG. (2024). Analysis of the Petroleum Industry Act's Impact on Taxation. Retrieved from home.kpmg/ng/en/home/insights/2024/02/pia-tax-impact.html

CPPA. (2024). Revenue Leakage in Nigeria's Oil Sector: An In-Depth Analysis. Retrieved from cppa-ng.org/research/revenue-leakage-2024

BudgIT. (2024). Budget Transparency Survey 2024: Oil Revenue and Public Welfare. Retrieved from www.yourbudgit.com/resource/budget-transparency-2024/

PwC. (2024). Nigerian Tax Policy Review: Challenges in Oil Revenue Collection. Retrieved from www.pwc.com/ng/en/publications/tax-policy-review-2024.pdf

Tax Justice Network. (2024). The Impact of Tax Havens on Nigeria's Oil Revenue. Retrieved from www.taxjustice.net/reports/nigeria-tax-havens-2024/

SWFI. (2024). The Performance of Nigeria's Sovereign Wealth Fund. Retrieved from www.swfinstitute.org/reports/nigeria-sovereign-wealth-2024

World Bank. (2024). Nigeria Economic Update: Bridging the Gap Between Oil Wealth and Development. Retrieved from www.worldbank.org/en/country/nigeria/publication/nigeria-economic-update-spring-2024

Reuters. (2024). Nigeria's Oil Sector: Challenges and Opportunities. Retrieved from www.reuters.com/world/africa/nigerias-oil-sector-challenges-opportunities-2024-02-15/

Reuters. (2024). Nigeria's Oil Sector: Challenges and Opportunities. Retrieved from www.reuters.com/world/africa/nigerias-oil-sector-challenges-opportunities-2024-02-15/

NEITI. (2024). 2024 Annual Report on Oil and Gas Revenue Transparency. Retrieved from www.neiti.gov.ng/index.php/annual-reports/2024

KPMG. (2024). Analysis of the Petroleum Industry Act's Impact on Taxation. Retrieved from home.kpmg/ng/en/home/insights/2024/02/pia-tax-impact.html

World Bank. (2024). Nigeria Economic Update: Navigating Oil and Economic Diversification. Retrieved from www.worldbank.org/en/country/nigeria/publication/nigeria-economic-update-spring-2024

African Development Bank. (2024). Review of Nigeria's Energy Sector Infrastructure. Retrieved from www.afdb.org/fileadmin/uploads/afdb/Documents/Publications/nigeria_energy_infrastructure_2024.pdf

International Crisis Group. (2024). Nigeria: The Persistent Threat of Militancy in the Niger Delta. Retrieved from www.crisisgroup.org/africa/west-africa/nigeria/nigeria-persistent-threat-militancy-niger-delta-2024

IEA. (2024). World Energy Outlook 2024: Nigeria's Energy Strategy. Retrieved from www.iea.org/reports/world-energy-outlook-2024/nigeria-energy-strategy

Transparency International. (2024). Corruption Perceptions Index 2024: Nigeria's Oil Sector. Retrieved from www.transparency.org/en/cpi/2024/index/nga