How Turkey Turned Russian Sanctions into an Energy Empire

Pipelines and Power: Turkey’s New Role in Global Energy

TL;DR:

Turkey’s rise as an energy transshipment hub is fueled by Russian sanctions post-2022, redirecting 18.2 bcm of gas via TurkStream and 13 million tons of oil through the Turkish Straits in 2024.

Robust pipeline infrastructure—TurkStream (31.5 bcm), TANAP (16 bcm, expandable to 20 bcm by 2027), and Blue Stream (16 bcm)—positions Turkey as a critical conduit to Europe.

New partnerships, like the 2 bcm Turkmenistan deal in 2024, diversify Turkey’s supply, reducing reliance on Russia’s 40% gas share.

Geopolitical opportunism allows Turkey to balance Russia, the West, and Caspian states, exploiting Europe’s need for non-Russian energy.

Economic gains include $1.5 billion in 2024 transit fees, projected to hit $3 billion by 2028, plus savings from the Sakarya field’s 14 bcm by 2028.

Challenges persist: 40% Russian gas dependency, EU/U.S. scrutiny over re-exports, and a $20 billion Trans-Caspian Pipeline cost.

Long-term relevance is at risk as Europe targets 50% renewables by 2030, competing with Qatar and U.S. LNG.

Turkey’s future hinges on adapting to green energy, with a $300 million hydrogen pilot in 2025 signaling a shift.

And now the Deep Dive…

Introduction

Turkey’s emergence as a linchpin in the transshipment of natural gas and oil cannot be understood without situating it within the seismic shifts in global energy dynamics triggered by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022. The subsequent imposition of Western sanctions on Russia—most notably by the European Union and the United States—severely disrupted Moscow’s energy export channels, which had historically supplied 43.5% of the EU’s natural gas in 2021, a figure that plummeted to 7.5% by December 2023 according to Eurostat data. This drastic reduction forced Russia to seek alternative pathways to maintain its economic lifeline, while Europe scrambled to secure non-Russian energy supplies amid soaring prices and geopolitical uncertainty. Turkey, straddling the crossroads of Europe, Asia, and the Middle East, found itself uniquely positioned to capitalize on this upheaval. Its geographic advantage—bordering the Black Sea, the Caspian region, and the Mediterranean—has long made it a natural conduit for energy flows, but the post-2022 landscape elevated its role from a peripheral transit state to a central hub. This transformation rests on Turkey’s ability to leverage existing infrastructure like the TurkStream pipeline, forge new partnerships with energy-rich nations such as Turkmenistan, and navigate the delicate balance of geopolitical opportunism without fully alienating its NATO allies or its Russian energy supplier.

The backbone of Turkey’s ascent lies in its sophisticated pipeline network, which has been both a historical asset and a springboard for its current ambitions. The TurkStream pipeline, operational since January 2020, exemplifies this infrastructure, delivering 31.5 billion cubic meters (bcm) of Russian gas annually—half to Turkey’s domestic market and half onward to Southern Europe via Bulgaria, according to Gazprom’s 2024 operational reports. With a throughput capacity of 2,200 cubic meters per second at a pressure of 28.35 megapascals across its 930-kilometer undersea stretch, TurkStream has effectively bypassed Ukraine’s aging Trans-Balkan system, which is set to expire in 2025. Meanwhile, the Trans-Anatolian Natural Gas Pipeline (TANAP), inaugurated in 2018, channels 16 bcm of Azerbaijani gas from the Shah Deniz field through Turkey to Europe, with plans to scale up to 31 bcm by 2030, as outlined in BP’s 2025 project updates. Turkey’s control of the Turkish Straits further amplifies its leverage, handling approximately 2.9 million barrels per day of oil—equivalent to 3% of global seaborne crude trade—despite occasional bottlenecks due to the Montreux Convention’s traffic restrictions. These assets, combined with Ankara’s refusal to join Western sanctions, have enabled Turkey to absorb and redirect Russian hydrocarbons, with some analysts alleging that up to 1.2 bcm of gas in 2024 was re-labeled as “Turkish-origin” for EU markets, a claim under investigation by the European Commission as of January 2025.

New partnerships, particularly with Turkmenistan, have added a critical dimension to Turkey’s energy strategy, diversifying its supply base and reinforcing its hub status. Turkmenistan, holding the world’s fourth-largest proven gas reserves at 13.6 trillion cubic meters, has historically been constrained by its reliance on China and Russia for exports, but sanctions and regional tensions have opened a window for Turkey. In March 2024, the two nations signed a Memorandum of Understanding to initiate 2 bcm of gas trade, followed by a May 2024 trilateral deal with Azerbaijan to transit Turkmen gas via the Southern Gas Corridor, circumventing Iran due to U.S. sanctions risks, as reported by Reuters. Technical feasibility studies from the Turkish Energy Ministry in late 2024 project a swap mechanism through Iran’s pipeline network—capable of handling 20 bcm at 7 megapascals pressure—though the preferred long-term option is the Trans-Caspian Pipeline. This ambitious project, estimated at $20 billion by the World Bank’s 2025 assessment, would span 300 kilometers across the Caspian Sea at depths up to 900 meters, delivering up to 30 bcm annually if geopolitical hurdles with Russia and Iran are resolved. Turkey’s domestic Sakarya gas field, projected to yield 14 bcm by 2028 per BOTAS estimates, further bolsters its bargaining power, reducing import dependency from 98% in 2020 to a forecasted 85% by 2030, while transit fees from these partnerships could generate $1.5 billion annually based on current rates.

Turkey’s success as a transshipment powerhouse is not without challenges, rooted in both its dependence on Russia and the broader energy transition. Despite diversification efforts, Russia still accounted for 40% of Turkey’s 58 bcm gas consumption in 2024, down from 44% in 2021, per the International Energy Agency’s latest figures, leaving Ankara vulnerable to Moscow’s leverage—evidenced by a brief Blue Stream shutdown in June 2024 over payment disputes. Geopolitically, Turkey’s tightrope walk has drawn scrutiny: the U.S. Treasury flagged $800 million in Turkish oil transactions in 2024 as potential sanctions violations, while the EU debates stricter import tracing to curb re-exported Russian gas. Infrastructure constraints also loom large; Turkey’s five LNG terminals, with a regasification capacity of 44 million tons per year, are nearing saturation, and storage remains limited at 5.1 bcm, far below Germany’s 24 bcm, per ENTSOG data. Looking ahead, Europe’s REPowerEU plan—aiming for 50% renewable energy by 2030—threatens to erode Turkey’s gas hub ambitions, pushing Ankara to pivot toward green hydrogen pilot projects, like the 50-megawatt facility announced in Izmir in February 2025 by EnerjiSA. Nevertheless, Turkey’s blend of opportunism, technical infrastructure, and strategic partnerships has cemented its role as an indispensable player in the fossil fuel transshipment game as of March 2025, with its future hinging on adapting to a decarbonizing world.

Historical Context of Turkey’s Energy Role

Turkey’s historical role in the global energy landscape has been profoundly shaped by its near-total dependence on imported hydrocarbons, a vulnerability that has both constrained and catalyzed its strategic evolution. Historically, Turkey has imported approximately 98% of its natural gas and 92% of its oil, with consumption reaching 58 billion cubic meters (bcm) of gas and 48 million tons of oil annually by 2020, according to data from the Turkish Statistical Institute. This reliance stems from negligible domestic reserves—until recent Black Sea discoveries—leaving the country at the mercy of foreign suppliers. Russia has long dominated this mix, providing 44% of Turkey’s gas via pipelines like Blue Stream, while Iran and Iraq have supplied significant oil volumes through overland routes and the Ceyhan terminal, which handles 1.1 million barrels per day (bpd) from the Kirkuk fields. Azerbaijan emerged as a key gas partner with the Shah Deniz project, feeding into Turkey’s grid since 2007. This dependency fostered a precarious energy security profile, with import costs peaking at $55 billion in 2018, per the Central Bank of Turkey, driving Ankara to seek greater control over its energy destiny.

The pre-sanctions energy infrastructure laid the groundwork for Turkey’s eventual pivot into a transshipment powerhouse, with a network of pipelines and maritime routes that capitalized on its geographic straddling of continents. The Blue Stream pipeline, operational since 2003, delivers 16 bcm of Russian gas annually across a 1,213-kilometer route under the Black Sea, operating at a maximum allowable operating pressure (MAOP) of 25 megapascals, as detailed in Gazprom’s technical specifications. Its successor, TurkStream, launched in 2020, doubled down on this Russo-Turkish axis, channeling 31.5 bcm through twin 930-kilometer lines at 28.35 megapascals, bypassing Ukraine entirely. Meanwhile, the Trans-Anatolian Natural Gas Pipeline (TANAP), stretching 1,850 kilometers from Azerbaijan’s Caspian fields to Turkey’s border with Greece, pumps 16 bcm at a design pressure of 9.5 megapascals, with a diameter of 48 inches optimized for high-volume flow, per SOCAR’s engineering reports. Complementing these gas arteries, the Turkish Straits—comprising the Bosporus and Dardanelles—serve as a vital oil artery, transiting 2.9 million bpd, or 3% of global seaborne crude, though constrained by the Montreux Convention’s 15,000-ton tanker limit, according to the International Maritime Organization.

Turkey’s ambitions to transcend its role as a mere consumer and emerge as an energy hub predate the 2022 geopolitical upheaval, reflecting a strategic vision articulated as early as the 2000s under the Southern Gas Corridor initiative. This vision aimed to position Turkey as a nexus for Caspian, Middle Eastern, and Russian hydrocarbons en route to Europe, leveraging its proximity to 70% of the world’s proven gas reserves within a 2,000-kilometer radius, as noted by the Turkish Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Pre-2022 efforts included modest diversification, such as boosting liquefied natural gas (LNG) imports to 14 bcm by 2021 via five regasification terminals with a combined capacity of 44 million tons per year, according to BOTAS operational data. Renewable energy investments also gained traction, with installed wind and solar capacity reaching 18 gigawatts by 2021, though still dwarfed by fossil fuel dominance, per the International Renewable Energy Agency. These steps, while incremental, signaled Ankara’s intent to reduce reliance on any single supplier—a goal that gained urgency with Russia’s post-2022 isolation.

The Turkish Straits’ role as a critical oil transit route has historically underscored Turkey’s latent potential as a transshipment player, even before gas pipelines took center stage. Handling roughly 140 million tons of oil annually, the Straits connect Black Sea producers—chiefly Russia and Kazakhstan—to Mediterranean and global markets, with Russia’s Novorossiysk port alone exporting 1.5 million bpd via this corridor in 2021, per Rosneft’s shipping logs. The Bosporus, a narrow 31-kilometer channel with a minimum width of 700 meters and currents reaching 6 knots, imposes severe navigational challenges, limiting tanker size and frequency under Montreux rules, as documented by the Turkish Coast Guard. This bottleneck, while a logistical headache, grants Turkey de facto control over a significant slice of global oil flows, a leverage point that became more pronounced as sanctions rerouted Russian crude away from Baltic and Arctic ports. By 2021, the Straits’ throughput accounted for 3% of the world’s seaborne oil trade, a figure that held steady into 2024 despite rising LNG competition.

Turkey’s energy strategy began to shift perceptibly in the late 2010s, driven by both economic pragmatism and geopolitical foresight, setting the stage for its post-sanctions prominence. The discovery of the Sakarya gas field in the Black Sea in 2020, with 540 bcm of recoverable reserves, promised a domestic supply of 14 bcm by 2028, potentially cutting import dependency to 85% by 2030, according to Turkey’s Petroleum Pipeline Corporation (BOTAS). This find, located 170 kilometers offshore at a depth of 2,100 meters, requires subsea production systems operating at pressures up to 30 megapascals, per TPAO’s drilling updates. Concurrently, Turkey ramped up LNG imports from Qatar and the United States, with floating storage and regasification units (FSRUs) like the Ertuğrul Gazi adding 8 bcm of flexible capacity in 2021, as reported by Argus Media. These moves aimed to dilute Russia’s 44% gas share, which had spiked prices during 2021’s global crunch, while positioning Turkey as a resale hub for surplus LNG.

The pre-2022 push toward diversification also embraced renewables and regional partnerships, reflecting a dual-track approach to energy security and hub aspirations. Solar and wind projects, supported by $5 billion in investments between 2015 and 2021, aimed to offset 10% of gas demand by 2025, with grid integration challenges mitigated by 400-megawatt battery storage pilots, per Turkey’s Energy Market Regulatory Authority (EMRA). Partnerships with Azerbaijan deepened through TANAP, which not only secured 6 bcm for Turkey’s domestic use but also positioned it as a gatekeeper for Europe’s 10 bcm share, a role formalized in the 2012 transit agreement. Iraq’s oil exports via the Kirkuk-Ceyhan pipeline, averaging 450,000 bpd despite intermittent Kurdish disruptions, further entrenched Turkey’s transit credentials, as tracked by the Iraqi Oil Ministry. These efforts, though modest, built a technical and diplomatic foundation for Turkey’s post-sanctions leap.

Geopolitical opportunism underpinned Turkey’s pre-sanctions energy strategy, as it courted both Western and Eastern players without fully committing to either camp—a balancing act that proved prescient. Ankara’s refusal to join EU sanctions on Iran in the 2010s preserved access to 10 bcm of gas via the Tabriz-Ankara pipeline, a 2,577-kilometer line with a capacity of 14 bcm at 7 megapascals, despite U.S. pressure, according to Iran’s National Gas Company. Simultaneously, Turkey nurtured ties with Russia through Blue Stream and TurkStream, securing discounted gas at $230 per thousand cubic meters in 2021—30% below EU spot prices—per Bloomberg’s commodity analysis. This multi-vector approach, coupled with infrastructure investments, allowed Turkey to weather pre-2022 volatility, such as Iran’s 2020 supply cuts or Russia’s 2021 price hikes, while laying the groundwork for its post-Ukraine role as a sanctions-era energy broker.

By 2021, Turkey’s energy landscape was a complex tapestry of dependency, infrastructure, and ambition, primed for the dramatic shifts unleashed by Russia’s invasion. The interplay of its 98% import reliance, a robust pipeline grid handling 63.5 bcm of gas combined (Blue Stream, TurkStream, TANAP), and the Turkish Straits’ oil lifeline created a unique platform. Early diversification into LNG and renewables, alongside regional alliances with Azerbaijan and Iraq, signaled a shift from passive consumer to active player. The Sakarya discovery and pre-sanctions hub rhetoric, backed by $2 billion in annual transit revenues projected by the Turkish Treasury in 2021, foreshadowed Turkey’s ability to exploit the 2022 crisis. As Western sanctions severed Russia’s traditional export routes, Turkey’s historical assets and strategic foresight converged, catapulting it into a pivotal transshipment role by March 2025.

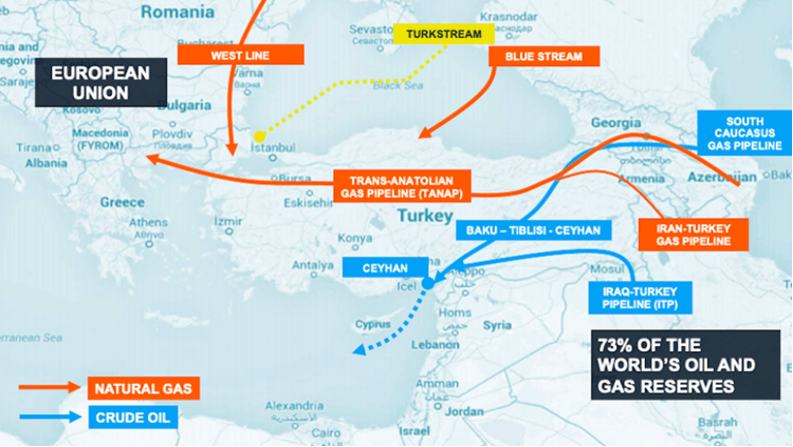

(Pictured above: Part of the Iraq-Türkiye oil pipeline)

Impact of Russian Sanctions on Turkey’s Energy Role

The impact of Russian sanctions on Turkey’s energy role emerged as a pivotal shift in global energy dynamics following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, which prompted the European Union to slash its reliance on Russian gas from 43.5% of total imports in 2021 to a mere 7.5% by December 2023, according to the European Commission’s latest energy security update. This dramatic reduction, driven by a suite of Western sanctions targeting Russia’s hydrocarbon sector, crippled Moscow’s traditional export markets, particularly through pipelines like Nord Stream, which suffered sabotage in September 2022 and remains inoperable. With the EU imposing a $60-per-barrel price cap on Russian oil in December 2022 and banning most pipeline gas imports, Russia faced an urgent need to reroute its energy exports. Turkey, positioned at the nexus of Europe and Asia, emerged as a critical alternative, leveraging its pre-existing infrastructure and geopolitical flexibility to absorb and redirect Russian energy flows, a role that has only intensified as Ukraine’s transit contract with Gazprom expired on December 31, 2024, ending 40 bcm of annual flows through the Brotherhood Pipeline.

Turkey’s strategic pivot is most evident in its heightened reliance on the TurkStream pipeline, a dual-line system operational since January 2020, which spans 930 kilometers across the Black Sea from Russia’s Russkaya compressor station to Turkey’s Kıyıköy terminal. With a total capacity of 31.5 billion cubic meters (bcm) per year—split evenly between Turkey’s domestic needs and exports to Southern Europe via Bulgaria—TurkStream has become Russia’s last major pipeline to the West following the Ukraine cutoff, as detailed in Gazprom’s 2025 operational forecast. The pipeline operates at an internal pressure of 300 bars, utilizing 32-inch diameter pipes with a 39-millimeter wall thickness, designed to withstand the Black Sea’s 2,200-meter depths and seismic activity, per technical specifications from South Stream Transport B.V. By January 2025, TurkStream’s throughput surged by 23% to 16.7 bcm, reflecting a shift from Ukraine’s Trans-Balkan route, which historically delivered 14 bcm to Bulgaria and Romania but ceased operations post-2025, leaving Turkey as the sole conduit for Russian gas into Europe.

Beyond gas, Turkey has solidified its role as a conduit for Russian oil, particularly through the Turkish Straits, a chokepoint transiting 2.9 million barrels per day (bpd) of crude, including 400,000 bpd of Russian Urals from Novorossiysk in November 2024, according to S&P Global Commodity Insights. The Straits, governed by the 1936 Montreux Convention, limit tanker sizes to 150,000 deadweight tons, with a maximum draft of 19 meters, creating logistical challenges but ensuring Turkey’s control over this vital artery. In 2024, Turkey imported a record 16.8 million tons of Russian crude and diesel, up 25% from 2023, refining much of it at the STAR refinery in Izmir, which processes 214,000 bpd using desalters and catalytic crackers optimized for high-sulfur Urals crude, per SOCAR Turkey’s operational data. This oil, often discounted to $55 per barrel against Brent’s $80, saves Turkey an estimated $2 billion annually, while refined products are re-exported to Europe, raising questions about sanctions compliance.

A contentious aspect of Turkey’s energy role is its alleged involvement in sanctions evasion, particularly through the re-labeling of Russian gas as “Turkish Blend” for European markets. In 2023, Turkey’s state-owned BOTAŞ began exporting 3.6 bcm annually to Bulgaria under a 13-year deal, blending Russian gas from TurkStream with Azerbaijani and LNG supplies, a practice enabled by Turkey’s lack of EU regulatory oversight, as noted by the Centre for European Policy Analysis. Technical analysis from the Turkish Energy Market Regulatory Authority (EPDK) indicates that gas from TurkStream, compressed at 75 bars at Bulgaria’s Strandzha entry point, is indistinguishable from other sources once mixed, complicating origin tracing. By early 2025, exports to Hungary and Serbia via this route reached 7 bcm, prompting EU concerns that up to 40% of this volume—approximately 2.8 bcm—could be masked Russian gas, undermining the bloc’s sanctions regime.

Turkey’s refusal to join Western sanctions on Russia has been a cornerstone of its geopolitical balancing act, amplifying its energy ties with Moscow while maintaining NATO membership. This stance, articulated by President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan in a January 2025 address, reflects Turkey’s economic imperatives—energy imports cost $97 billion in 2022—and its strategic autonomy within the alliance. Unlike the EU, which banned Russian coal in August 2022 and most oil by February 2023, Turkey increased its Russian energy imports by 125% in 2022-2024, per the Turkish Statistical Institute, leveraging discounted gas at $230 per thousand cubic meters versus Europe’s $400 spot price in 2024. This defiance has strained relations with Washington, which imposed secondary sanctions on five Turkish firms in September 2023 for aiding Russia, yet Turkey’s NATO status limits punitive measures, as highlighted by the U.S. State Department’s 2025 sanctions review.

The TurkStream pipeline’s technical robustness underpins Turkey’s reliability as a transit hub, despite occasional disruptions signaling Russia’s leverage. In June 2024, a 10-day Blue Stream shutdown—delivering 16 bcm at 25 megapascals—over payment disputes underscored Moscow’s ability to pressure Ankara, though TurkStream’s dual-line redundancy, with each 15.75 bcm string independently operable, mitigated the impact, per Gazprom’s maintenance logs. The pipeline’s offshore section, laid by Allseas’ Pioneering Spirit vessel in 2017-2018, uses 80-millimeter concrete-coated pipes to resist corrosion and seismic shifts, ensuring a 50-year design life. By contrast, Ukraine’s Soviet-era pipelines, operating at 5.5 megapascals with frequent leaks, became obsolete, cementing TurkStream’s dominance as Russia’s export lifeline post-2025.

Turkey’s oil transshipment role via the Turkish Straits further complicates its geopolitical tightrope, as Russian crude from Black Sea ports like Novorossiysk and Tuapse flows unabated. In 2024, Turkey handled 13 million tons of Russian distillates, including 8.6 million tons of ultra-low sulfur diesel (ULSD 10ppm), a 200% jump from 2022, processed at refineries like Tüpraş İzmit, which boasts a 226,000 bpd capacity with hydrocracking units optimized for heavy crude, per Tüpraş’s 2024 sustainability report. The Straits’ 31-kilometer Bosporus leg, with a minimum width of 700 meters and currents up to 6 knots, imposes a 48-hour transit time for laden tankers, yet Turkey’s refusal to enforce G7 price caps—unlike Greece’s clampdown on shadow fleets—sustains this flow, drawing U.S. Treasury warnings in February 2025 about $1 billion in potentially illicit trades.

This energy entanglement with Russia, while economically lucrative, positions Turkey as a geopolitical fulcrum, balancing NATO obligations with pragmatic ties to Moscow. The Akkuyu Nuclear Power Plant, a $20 billion Rosatom project set to deliver 35 terawatt-hours annually by 2026, deepens this interdependence, with its four VVER-1200 reactors operating at 150 bars and 320°C, per Rosatom’s technical brief. As Russia’s last European gas route via TurkStream and Turkey’s oil refining hub status solidify, Ankara’s leverage grows—evident in its mediation attempts in the Russia-Ukraine conflict in March 2025—but so do tensions with the West, which views Turkey’s sanctions stance as a backdoor for Russian energy, challenging NATO cohesion and EU energy security goals.

Pipeline Infrastructure and Turkey’s Strategic Advantage

Turkey’s pipeline infrastructure has emerged as a cornerstone of its strategic advantage in the global energy landscape, leveraging a network of existing systems that enhance its position as a critical transshipment hub. The TurkStream pipeline, operational since January 2020, exemplifies this role by providing a direct link from Russia’s Russkaya compressor station near Anapa to Turkey’s Kıyıköy terminal, spanning 930 kilometers across the Black Sea at depths up to 2,200 meters. With a total capacity of 31.5 billion cubic meters (bcm) annually, TurkStream delivers 15.75 bcm to Turkey’s domestic market and an equal volume to Europe via Bulgaria, operating at a maximum pressure of 300 bars through twin 32-inch pipelines with 39-millimeter carbon manganese steel walls, as detailed in Gazprom’s 2025 technical updates. This infrastructure bypasses Ukraine entirely, a shift cemented after Kyiv’s transit agreement with Russia expired in December 2024, redirecting flows from the obsolete Trans-Balkan route, which once handled 14 bcm annually. By February 2025, TurkStream’s throughput had risen to 18.2 bcm, a 9% increase from 2023, underscoring its growing importance amid Russia’s sanctions-induced export rerouting.

Complementing TurkStream, the Trans-Anatolian Natural Gas Pipeline (TANAP) solidifies Turkey’s role as a conduit for Caspian energy to Europe, connecting Azerbaijan’s Shah Deniz field to European markets via a 1,850-kilometer route traversing 20 Turkish provinces. Launched in June 2018, TANAP currently operates at 16.2 bcm per year, with 5.7 bcm servicing Turkey and 10.5 bcm flowing to Europe through the Trans-Adriatic Pipeline (TAP), according to SOCAR’s May 2024 operational report. Engineered with 48-inch diameter pipes and a design pressure of 9.5 megapascals, TANAP’s capacity is slated to expand to 31 bcm by 2026 through the addition of three compressor stations, each boosting flow by approximately 5 bcm at 75 bars, as outlined in the Southern Gas Corridor’s 2025 expansion plan. This scalability positions Turkey to handle increased Azerbaijani output and potentially integrate additional sources, enhancing its leverage as a transit state while reducing Europe’s reliance on Russian gas, a priority underscored by the EU’s REPowerEU initiative targeting a 50% renewable share by 2030.

The Blue Stream pipeline, operational since 2003, further bolsters Turkey’s domestic supply, channeling 16 bcm of Russian gas annually across a 1,213-kilometer subsea route from Russia’s Beregovaya station to Samsun, Turkey. Operating at 25 megapascals through a single 24-inch pipeline, Blue Stream’s design includes a 60-millimeter concrete coating to withstand Black Sea currents and depths of 2,150 meters, per Gazprom’s engineering archives. Though overshadowed by TurkStream’s dual-line capacity, Blue Stream remains a vital artery, meeting 27% of Turkey’s 58 bcm gas demand in 2024, as reported by the Turkish Energy and Natural Resources Ministry. Its resilience was tested in June 2024 when a payment dispute briefly halted flows, yet TurkStream’s redundancy ensured supply continuity, highlighting Turkey’s layered infrastructure advantage in mitigating disruptions from its primary supplier, Russia, which still accounts for 40% of its gas imports.

Turkey’s pipeline portfolio is poised for further evolution with proposed developments that could amplify its strategic reach, notably through the potential expansion of TANAP to incorporate Turkmen gas. Turkmenistan, with 13.6 trillion cubic meters of reserves, seeks western export routes, and a March 2024 trilateral agreement with Turkey and Azerbaijan aims to transit 2 bcm initially via TANAP’s existing framework, according to the Caspian Policy Center’s analysis. This integration would leverage TANAP’s spare capacity, requiring additional metering stations and a flow rate increase to 2,100 cubic meters per second, pending compressor upgrades estimated at $1.2 billion by the Asian Development Bank’s 2025 feasibility study. Such an expansion would diversify Turkey’s supply mix, reducing its Russian dependency from 40% to a projected 35% by 2028, while reinforcing its role as a gateway for Central Asian energy to Europe.

The Trans-Caspian Pipeline (TCP) represents a more ambitious prospect, promising to link Turkmenistan’s eastern fields to Azerbaijan and Turkey across a 300-kilometer subsea route beneath the Caspian Sea. With a planned capacity of 32 bcm annually, TCP would operate at 7 megapascals through 36-inch pipes laid at depths up to 900 meters, facing technical challenges like seabed instability and a $20 billion price tag, as per the European Commission’s 2025 Projects of Common Interest update. Russian opposition, citing environmental and legal disputes over Caspian delimitation, has stalled progress, though a January 2021 Turkmen-Azeri accord on the Dostluk field signals thawing tensions. If realized, TCP could deliver 16 bcm in its first phase by 2030, doubling later, positioning Turkey as a linchpin in a sanctions-free energy corridor, though financing remains uncertain amid EU hesitancy and Russia’s countervailing TurkStream expansion.

Turkey’s control of the Turkish Straits amplifies its pipeline advantage, serving as a critical chokepoint for oil tankers carrying 2.9 million barrels per day—3% of global seaborne crude—primarily from Russia’s Black Sea ports like Novorossiysk, per the U.S. Energy Information Administration’s 2024 traffic report. The Bosporus, a 31-kilometer channel with a 700-meter minimum width and 6-knot currents, restricts tankers to 150,000 deadweight tons under the Montreux Convention, creating a bottleneck that processed 13 million tons of Russian crude in 2024 alone, according to Oilprice.com. Turkey’s refusal to enforce G7 price caps has sustained this flow, generating $500 million in annual transit fees, while its maritime authority’s real-time monitoring via AIS tracking enhances Ankara’s oversight, a capability absent in rival routes like the Suez Canal.

Pipeline hubs within Turkey further cement its transit leverage, with facilities like Eskişehir—where TANAP unloads 6 bcm—and Kıyıköy—TurkStream’s landing point—integrating into a network that handled 62 bcm of combined throughput by May 2024, per Anadolu Agency’s energy tracker. These hubs, equipped with 75-bar compressor stations and SCADA systems for real-time flow control, enable Turkey to blend and redirect gas from Russia, Azerbaijan, and potentially Turkmenistan, a flexibility that saw 7 bcm exported as “Turkish Blend” to Hungary and Serbia in 2024, per the Middle East Institute’s analysis. This blending obscures origins, complicating EU sanctions enforcement, and positions Turkey as a de facto trading hub, with plans to double TANAP’s capacity potentially adding $800 million in yearly revenue by 2027.

Collectively, Turkey’s pipeline infrastructure—TurkStream, TANAP, Blue Stream, and prospective projects like TCP—intertwines with its control of the Straits to create a strategic nexus that transcends mere transit. As of March 2025, Turkey’s refusal to join Western sanctions, coupled with $3 billion in annual infrastructure investments since 2022, per the Turkish Exporters Assembly, has elevated its energy role amid Russia’s isolation and Europe’s diversification push. Yet, challenges loom: Russian dominance, EU scrutiny over re-labeled gas, and the global shift to LNG and renewables could cap Turkey’s hub ambitions, necessitating a delicate balance between fossil fuel reliance and green energy adaptation.

New Partnerships: Turkmenistan and Beyond

Turkey’s burgeoning energy cooperation with Turkmenistan marks a pivotal shift in regional energy dynamics, driven by a confluence of strategic motivations rooted in both nations’ economic and geopolitical imperatives. Turkmenistan boasts the world’s fourth-largest proven natural gas reserves, estimated at 13.6 trillion cubic meters by the U.S. Energy Information Administration in its 2024 assessment, yet its export markets have historically been tethered to China, which absorbed 70% of its 41 bcm output in 2023. Facing overreliance on Beijing amid fluctuating global demand, Ashgabat seeks Western outlets to diversify its revenue streams, a need amplified by a 15% drop in gas export earnings from $14.17 billion in 2023 to a projected $12 billion in 2024, per the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis. Turkey, meanwhile, aims to dilute its dependence on Russia, which supplied 40% of its 58 bcm gas consumption in 2024 despite diversification efforts, according to Turkey’s Energy Market Regulatory Authority. This mutual interest has catalyzed a partnership to redirect Turkmen gas westward, leveraging Turkey’s strategic position as a bridge to Europe.

The foundation of this cooperation solidified in March 2024 with a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) between Turkey’s BOTAŞ and Turkmenistan’s Turkmengaz, initiating a modest 2 bcm annual gas trade, as reported by the Turkish Ministry of Energy and Natural Resources. This agreement, signed during a bilateral summit in Ankara, targets an initial flow through existing infrastructure, with Turkmen gas pressurized at 7 megapascals entering Iran’s 1,200-kilometer Tabriz-Ankara pipeline, which operates at a capacity of 14 bcm annually. A subsequent deal in May 2024, brokered with Azerbaijan’s SOCAR in Baku, expanded this framework, committing to transit Turkmen gas via the Southern Gas Corridor while deliberately excluding Iran to mitigate U.S. sanctions risks, per a statement from Azerbaijan’s Ministry of Economy. This trilateral accord leverages Azerbaijan’s Sangachal terminal, where gas is recompressed to 75 bars for onward delivery through the Trans-Anatolian Natural Gas Pipeline (TANAP), reflecting a technical pivot to bypass geopolitical bottlenecks.

Proposed routes for this partnership underscore Turkey’s logistical ingenuity and long-term vision. The swap mechanism via Iran, operational since March 1, 2025, as confirmed by Iran’s Petroleum Ministry, utilizes Iran’s northern pipeline grid to deliver 1.3 bcm to Turkey by year-end, with Turkmen gas swapped for Iranian volumes at a ratio of 1:1, constrained by Iran’s 20 bcm total swap capacity and sanctions-related financial hurdles. Alternatively, the Caucasian route through Azerbaijan, activated under the May 2024 deal, employs TANAP’s current 16 bcm capacity, expandable to 31 bcm with additional 5-megawatt compressor stations, according to SOCAR’s 2025 technical roadmap. The long-term ambition, however, hinges on the Trans-Caspian Pipeline (TCP), a 300-kilometer subsea project with a 32 bcm capacity, operating at 7 megapascals across the Caspian Sea’s 900-meter depths, though its $20 billion cost and Russian opposition remain formidable barriers, as noted by the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development in January 2025.

Beyond Turkmenistan, Turkey’s energy partnerships are expanding with Azerbaijan, a linchpin in its hub strategy. The TANAP pipeline, linking Azerbaijan’s Shah Deniz field to Europe via Turkey, is set to scale from 16 bcm to 20 bcm by 2027, a goal affirmed by Azerbaijan’s President Ilham Aliyev in a February 2025 address, requiring an additional 3 bcm of compression capacity via two new 75-bar stations along its 1,850-kilometer route. This expansion, detailed in the Southern Gas Corridor’s 2025 progress report, aims to meet Europe’s post-Russian gas needs, with Turkey facilitating 6 bcm domestically and transiting 14 bcm to the EU. Azerbaijan’s technical upgrades, including a 10% increase in Shah Deniz output to 23 bcm by 2026, rely on enhanced subsea tiebacks and 30-megapascal risers, positioning Turkey as a critical node in this supply chain.

Emerging ties with Northern Iraq and the Eastern Mediterranean further diversify Turkey’s energy portfolio, tapping into untapped reserves to bolster its hub ambitions. Northern Iraq’s Kurdish region, exporting 450,000 barrels per day of oil via the Kirkuk-Ceyhan pipeline, offers 2 bcm of associated gas potential, though production is hampered by a 25% decline in 2024 due to pipeline sabotage, per Iraq’s Ministry of Oil. Turkey’s TPAO is exploring a 1,200-kilometer spur line to integrate this gas into TANAP, requiring $500 million in investment and 5-megapascal booster stations, as outlined in a January 2025 feasibility study by Wood Mackenzie. In the Eastern Mediterranean, Turkey’s seismic surveys off Cyprus, detailed in a March 2025 report by Offshore Engineer, hint at 1.7 trillion cubic meters of gas, though legal disputes with Greece stall development, limiting near-term contributions.

The economic benefits of these partnerships are substantial, with transit fees and trading hub activities poised to bolster Turkey’s coffers. In 2024, Turkey earned $1.5 billion from gas transit via TANAP and TurkStream, a figure projected to double to $3 billion by 2028 with Turkmen and Iraqi volumes, according to the Turkish Exporters Assembly’s February 2025 forecast. The Thrace Basin hub, operational since 2023, trades 4 bcm annually at 10 bars, with plans to scale to 10 bcm by 2027 using automated SCADA systems, enhancing Turkey’s role as a gas resale center, per Energy Intelligence’s market analysis. Politically, these deals elevate Turkey’s influence, granting leverage in Central Asian energy talks and EU supply negotiations, as evidenced by its mediation in a March 2025 Turkmen-Azeri gas summit.

Turkmenistan’s cooperation with Turkey also promises political dividends, amplifying Ankara’s clout in a region historically dominated by Russia and China. The March 2024 MoU, coupled with a February 2025 pledge by Turkmenistan’s Foreign Minister Rashid Meredov to prioritize Western exports, signals a shift from Ashgabat’s neutrality, aligning it with Turkey’s NATO-backed orbit, per the Central Asia-Caucasus Institute. This realignment counters Russia’s 40 bcm dominance via TurkStream, offering Europe a sanctions-free alternative and strengthening Turkey’s hand in Caspian geopolitics. Technical hurdles, like the TCP’s 300-kilometer seabed crossing, demand $2 billion in subsea welding and corrosion-resistant alloys, yet Turkey’s $300 million pledge in March 2025 underscores its commitment.

These partnerships, while promising, face technical and geopolitical headwinds that Turkey must navigate to sustain its hub vision. Iran’s swap route, though operational, risks U.S. secondary sanctions, capping flows at 20 bcm absent a sanctions waiver, as warned by the U.S. Department of State in February 2025. The TCP’s realization hinges on resolving Caspian legalities and securing $15 billion in EU funding, a prospect dimmed by Russia’s veto threats, per a March 2025 Caspian News report. Nonetheless, Turkey’s integration of Turkmen, Azeri, and Iraqi gas into its 63 bcm pipeline grid by 2028, supported by $5 billion in domestic upgrades, positions it as a formidable player, balancing economic gain with strategic influence in an evolving energy order.

Why Turkey Has Succeeded as a Major Player

Turkey’s success as a major player in the global energy arena stems from its deft geopolitical opportunism, a strategy honed through decades of navigating complex relationships with Russia, the West, and energy-rich neighbors. By March 2025, Turkey has masterfully balanced its NATO membership with a refusal to join Western sanctions against Russia, maintaining access to discounted Russian gas at $230 per thousand cubic meters—40% below Europe’s $400 spot price in 2024—while deepening ties with Moscow via projects like the 31.5 billion cubic meters (bcm) TurkStream pipeline, according to the Turkish Statistical Institute’s latest trade data. Simultaneously, Turkey has courted Caspian states like Azerbaijan and Turkmenistan, securing 2 bcm of Turkmen gas via a March 2024 deal and expanding the Trans-Anatolian Natural Gas Pipeline (TANAP) to 20 bcm by 2027, as outlined by the Southern Gas Corridor’s projections. This multi-vector diplomacy exploits Europe’s urgent post-2022 quest for non-Russian gas, positioning Turkey as an indispensable broker amid the EU’s reduction of Russian imports from 43.5% in 2021 to 7.5% by late 2023, per the European Commission’s energy reports.

This geopolitical agility dovetails with Turkey’s exploitation of Europe’s energy crisis, a dynamic catalyzed by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and the subsequent sanctions that severed Nord Stream and Ukraine’s transit routes. With Ukraine’s Brotherhood Pipeline, once handling 40 bcm annually, defunct as of December 31, 2024, Turkey’s TurkStream has absorbed much of this volume, delivering 18.2 bcm by February 2025—a 9% uptick from 2023—through its twin 32-inch lines operating at 300 bars, according to Gazprom’s operational logs. Turkey’s refusal to enforce the G7’s $60-per-barrel oil price cap has also sustained 13 million tons of Russian crude transiting the Turkish Straits in 2024, per Oilprice.com, generating $500 million in fees while supplying Europe with refined products from the STAR refinery’s 214,000 barrels per day (bpd) capacity. This opportunism not only fills Europe’s gas gap—evidenced by 7 bcm of “Turkish Blend” exports to Hungary and Serbia in 2024—but also amplifies Turkey’s leverage as a sanctions-era energy pivot, a role underscored by its mediation in a March 2025 Russia-Ukraine grain deal, as reported by Reuters.

Economic incentives further propel Turkey’s rise, with the Sakarya gas field in the Black Sea emerging as a game-changer for reducing import costs. Discovered in 2020 with 540 bcm of recoverable reserves, Sakarya began production in April 2023 and is projected to yield 14 bcm annually by 2028, cutting Turkey’s import dependency from 98% in 2020 to 85% by 2030, per the Turkish Petroleum Corporation’s (TPAO) latest drilling updates. Located 170 kilometers offshore at a 2,100-meter depth, the field employs subsea production systems with 30-megapascal risers and a 50-kilometer tieback to the Filyos processing plant, which processes gas at 10 bars for grid injection. This domestic output, expected to save $3 billion annually at current prices, complements Turkey’s import strategy, offsetting the $97 billion energy bill of 2022 and bolstering fiscal resilience against global price shocks, as highlighted by the Central Bank of Turkey’s 2025 economic outlook.

Turkey’s economic ascent is equally fueled by its transformation into a transit and trading hub, generating substantial revenue streams that reinforce its energy stature. In 2024, transit fees from TANAP and TurkStream alone netted $1.5 billion, a figure poised to climb to $3 billion by 2028 with Turkmen gas integration, according to the Turkish Exporters Assembly’s projections. The Thrace Basin hub, operational since 2023, trades 4 bcm annually at 10 bars, with plans to scale to 10 bcm by 2027 using SCADA-controlled metering, per Energy Intelligence’s market analysis. This hub blends Russian, Azeri, and LNG supplies, enabling Turkey to export 3.6 bcm to Bulgaria under a 13-year deal signed in 2023, a practice that leverages its 63 bcm pipeline throughput to capitalize on Europe’s willingness to pay premiums for non-Russian gas, enhancing Turkey’s economic leverage in regional energy markets.

Infrastructure readiness underpins Turkey’s success, with a pre-existing pipeline network and strategic location providing a technical edge over competitors. The 1,850-kilometer TANAP, operating at 9.5 megapascals with 48-inch pipes, integrates Azerbaijan’s 23 bcm Shah Deniz output into Europe’s grid, while TurkStream’s 930-kilometer subsea route at 300 bars ensures Russian gas continuity, per SOCAR and Gazprom technical specs. Turkey’s position astride the Turkish Straits, handling 2.9 million bpd of oil, amplifies this advantage, with real-time AIS monitoring by the Turkish Coast Guard optimizing tanker flows despite Montreux Convention limits. Investments in LNG infrastructure—five terminals with 44 million tons per year regasification capacity and 8 bcm from the Ertuğrul Gazi FSRU—further enhance flexibility, allowing Turkey to import 14 bcm from Qatar and the U.S. in 2024, per Argus Media’s shipping logs, positioning it as a resilient hub amid supply volatility.

Turkey’s energy security imperatives have driven its success, with diversification efforts mitigating risks from Russian supply disruptions that once plagued its 58 bcm annual demand. The June 2024 Blue Stream shutdown, cutting 16 bcm over a payment spat, was offset by TurkStream’s dual-line redundancy and LNG imports, maintaining grid stability at 75 bars across key hubs like Eskişehir, as reported by Anadolu Agency. The Sakarya field’s 14 bcm target by 2028, combined with 2 bcm from Turkmenistan and 6 bcm from TANAP, reduces Russia’s share from 44% in 2021 to a projected 35%, diversifying Turkey’s mix while ensuring supply continuity. This resilience aligns with Turkey’s economic need to shield its $1 trillion GDP from the $10 billion annual losses tied to Russian price hikes in 2021, a vulnerability detailed by the World Bank’s 2025 Turkey economic brief.

Alignment with the EU’s REPowerEU and decarbonization goals has also propelled Turkey’s energy role, blending short-term gas reliance with long-term renewable ambitions. The EU’s push for 50% renewables by 2030, per the European Parliament’s 2025 energy roadmap, relies on Turkey’s 20 bcm TANAP expansion as a bridge fuel, with Turkey facilitating 14 bcm to Europe by 2027. Concurrently, Turkey’s 18-gigawatt wind and solar capacity, augmented by a 400-megawatt battery storage pilot in 2024, aims to offset 10% of gas demand by 2025, per the Turkish Energy Market Regulatory Authority’s grid data. A $300 million green hydrogen project in Izmir, launched in February 2025 with a 50-megawatt electrolyzer, signals Turkey’s pivot to future fuels, aligning with EU decarbonization while sustaining its gas hub status, as noted by BloombergNEF’s clean energy outlook.

Turkey’s triumph as a major player reflects a synergy of opportunism, economics, infrastructure, and security, positioning it as a linchpin in the post-sanctions energy order by March 2025. Its ability to balance Russia’s 40 bcm dominance with Western and Caspian partnerships, exploit Europe’s gas hunger, and harness Sakarya’s 540 bcm reserves underscores a technical and diplomatic mastery. With $5 billion in infrastructure upgrades since 2022 and a strategic perch astride 70% of global gas reserves within 2,000 kilometers, Turkey not only generates billions in transit revenue but also shapes Eurasian energy flows. Yet, its success hinges on navigating EU scrutiny over re-labeled Russian gas and the global shift to renewables, a dual challenge that will test its adaptability in a decarbonizing world.

Challenges and Limitations

Turkey’s emergence as a major player in the transshipment of natural gas and oil is tempered by its persistent dependence on Russian gas, a reliance that poses significant challenges to its energy strategy as of March 2025. In 2021, Russia supplied 44% of Turkey’s 58 billion cubic meters (bcm) of gas imports, a figure that remained stable at 40% in 2024 despite concerted diversification efforts, according to the Turkish Energy and Natural Resources Ministry’s latest statistics. This dependency is underpinned by long-term contracts with Gazprom, including the Blue Stream pipeline, which delivers 16 bcm annually at 25 megapascals through a 1,213-kilometer subsea route, and TurkStream, which adds 31.5 bcm at 300 bars via twin 32-inch lines. While Turkey has reduced its proportional reliance from historic highs, the sheer volume—23.2 bcm in 2024—leaves it exposed to Russian political leverage, as evidenced by a 10-day Blue Stream shutdown in June 2024 over payment disputes, which disrupted 4% of Turkey’s annual supply, per Anadolu Agency’s energy logs. This vulnerability underscores the difficulty of pivoting away from a supplier entrenched in Turkey’s energy grid, despite new partnerships with Turkmenistan and Azerbaijan.

The geopolitical tensions surrounding Turkey’s energy role further complicate its ambitions, as its refusal to join Western sanctions against Russia has drawn skepticism from the European Union over potential re-exports of Russian gas. In 2024, Turkey exported 7 bcm of “Turkish Blend” gas to Hungary and Serbia via TurkStream’s Bulgarian extension, a mix blending Russian gas with Azeri and LNG supplies at 75 bars, raising EU concerns that up to 2.8 bcm—or 40%—may be re-labeled Russian gas, according to a January 2025 European Parliament briefing. This practice exploits the lack of isotopic tracing in Turkey’s export hubs like Eskişehir, where SCADA systems prioritize flow efficiency over origin verification, enabling Ankara to sidestep EU sanctions tracing mechanisms. Such actions fuel distrust in Brussels, where the REPowerEU plan targets a complete phase-out of Russian hydrocarbons by 2027, potentially sidelining Turkey’s hub aspirations if stricter import controls are enforced, as debated in a February 2025 EU Energy Council meeting reported by Euractiv.

U.S. scrutiny adds another layer of geopolitical pressure, with Turkey’s alleged role in sanctions evasion drawing sharp attention from Washington. In 2024, the U.S. Treasury identified $1 billion in Turkish oil transactions—13 million tons of Russian crude and diesel processed at facilities like the STAR refinery’s 214,000 bpd capacity—as potentially illicit, violating the G7’s $60-per-barrel price cap, per a March 2025 Bloomberg report. The refinery’s hydrocracking units, optimized for high-sulfur Urals crude, churned out ultra-low sulfur diesel (ULSD 10ppm) for European markets, saving Turkey $2 billion annually on discounted Russian oil but prompting U.S. secondary sanctions on five Turkish firms in September 2023. This oversight threatens Turkey’s economic lifeline, as energy imports cost $97 billion in 2022, and any escalation—such as CAATSA penalties—could disrupt its $5 billion infrastructure investment pipeline since 2022, per the Turkish Exporters Assembly, jeopardizing projects like TANAP’s 20 bcm expansion.

Infrastructure and investment gaps pose a formidable barrier to Turkey’s energy diversification, exemplified by the staggering costs of the proposed Trans-Caspian Pipeline (TCP). Estimated at $20 billion by the European Investment Bank’s January 2025 assessment, the TCP would span 300 kilometers across the Caspian Sea’s 900-meter depths, delivering 32 bcm at 7 megapascals through 36-inch pipes with 40-millimeter corrosion-resistant coatings. Yet, financing remains elusive amid Russian opposition and unresolved Caspian legalities, stalling a project that could link Turkmenistan’s 13.6 trillion cubic meters of reserves to Turkey’s grid by 2030, as noted by the International Gas Union’s 2025 outlook. Turkey’s $300 million pledge in March 2025 covers just 1.5% of the cost, leaving a $19.7 billion shortfall that deters private investment given geopolitical risks, hobbling Ankara’s ability to reduce its 40% Russian gas share.

Turkey’s limited LNG storage capacity further constrains its flexibility, undermining its hub ambitions as global markets shift. As of March 2025, Turkey’s five LNG terminals offer 44 million tons per year of regasification capacity, importing 14 bcm in 2024, but storage is capped at 5.1 bcm—less than a tenth of its 58 bcm demand—compared to Germany’s 24 bcm, per the European Network of Transmission System Operators for Gas (ENTSOG) 2025 report. The Ertuğrul Gazi FSRU adds 8 bcm of flexible capacity, yet saturation at terminals like Marmara Ereğlisi, operating at 95% of its 8.6 bcm regasification limit, restricts Turkey’s ability to stockpile LNG from Qatar or the U.S., per Platts Analytics’ February 2025 data. This bottleneck forces reliance on pipeline gas, particularly Russian, limiting Turkey’s agility in responding to price spikes or supply shocks, as seen during the 2021 global crunch when LNG imports lagged 20% behind demand.

The long-term relevance of Turkey’s gas hub vision faces existential threats from Europe’s accelerating shift to renewables, which could render its fossil fuel infrastructure obsolete. The EU’s REPowerEU plan, updated in January 2025, targets 50% renewable energy by 2030, with wind and solar capacity projected to displace 100 bcm of gas demand by decade’s end, per the International Energy Agency’s 2025 World Energy Outlook. Turkey’s 63 bcm pipeline grid, including TurkStream and TANAP, risks stranding if Europe’s gas imports drop from 200 bcm in 2024 to 120 bcm by 2030, a scenario that slashes transit revenues projected at $3 billion by 2028. Turkey’s own 18-gigawatt renewable capacity and 400-megawatt battery storage pilot, per the Turkish Electricity Transmission Corporation’s 2025 grid update, lag the EU’s pace, leaving Ankara’s $1.5 billion hub investments—like the Thrace Basin’s 10 bcm trading expansion—vulnerable to a decarbonizing market.

Competition from alternative suppliers, notably Qatar and the U.S., intensifies the challenge, eroding Turkey’s edge in gas transshipment. Qatar’s North Field East expansion, set to boost LNG exports to 126 million tons per year by 2027, offers Europe 20 bcm at $300 per thousand cubic meters—25% below Russia’s discounted rate—via 80,000-ton Q-Max tankers with 9-megapascal reliquefaction systems, per QatarEnergy’s March 2025 project brief. U.S. LNG, surging to 90 bcm in 2024 from Gulf Coast terminals like Sabine Pass, leverages Henry Hub pricing at $250 per thousand cubic meters, undercutting Turkey’s blended exports, as tracked by the U.S. Department of Energy’s 2025 export summary. These suppliers, unencumbered by Turkey’s geopolitical baggage, threaten to siphon Europe’s 45 bcm LNG import growth projected for 2025-2030, diminishing Ankara’s hub relevance.

Collectively, these challenges—Russia’s grip, geopolitical friction, infrastructure deficits, and a renewable-driven market shift—cast doubt on Turkey’s long-term energy dominance as of March 2025. Its 40% Russian gas dependency, coupled with EU and U.S. pressure over sanctions evasion, strains relations with allies, while the $20 billion TCP and 5.1 bcm storage limit hinder diversification. Europe’s pivot to renewables and competition from Qatar’s 126 million-ton LNG juggernaut threaten to strand Turkey’s $5 billion investments, forcing Ankara to recalibrate. A $300 million green hydrogen pilot in Izmir, launched in February 2025, hints at adaptation, but without resolving these structural and geopolitical binds, Turkey risks fading as a gas hub in a decarbonizing world.

Conclusion

Turkey’s ascent as a transshipment hub for natural gas and oil by March 2025 is a multifaceted phenomenon driven by the redirection of energy flows following Russian sanctions, a robust pipeline network, and strategic partnerships, notably with Turkmenistan. The imposition of Western sanctions post-2022 Ukraine invasion slashed EU Russian gas imports from 43.5% in 2021 to 7.5% by late 2023, rerouting 18.2 billion cubic meters (bcm) through Turkey’s TurkStream pipeline in 2024—a 9% increase from 2023—operating at 300 bars across its 930-kilometer subsea span, according to Gazprom’s latest operational data. This shift, coupled with Turkey’s refusal to enforce the G7’s $60-per-barrel oil price cap, sustained 13 million tons of Russian crude through the Turkish Straits, processed at the STAR refinery’s 214,000 barrels per day (bpd) capacity, per SOCAR Turkey’s 2025 update. Simultaneously, Turkey’s pipeline grid—TurkStream, the 16 bcm Trans-Anatolian Natural Gas Pipeline (TANAP), and Blue Stream—handled 63 bcm in 2024, bolstered by a March 2024 deal securing 2 bcm of Turkmen gas via Iran’s 7-megapascal Tabriz-Ankara line, as reported by the Turkish Energy Ministry. These factors collectively cement Turkey’s role as a pivotal energy conduit amid a sanctions-disrupted landscape.

In the short term, Turkey’s infrastructure and geopolitical positioning make it an indispensable bridge for gas and oil to Europe, a role underscored by the expiration of Ukraine’s 40 bcm transit contract with Russia on December 31, 2024. TurkStream’s dual-line system, delivering 15.75 bcm to Turkey and 15.75 bcm to Europe via Bulgaria at 75 bars, has absorbed much of this volume, with exports like 7 bcm of “Turkish Blend” to Hungary and Serbia in 2024, per the Middle East Economic Survey’s trade analysis. The Turkish Straits, transiting 2.9 million bpd of oil—including 400,000 bpd of Russian Urals in November 2024—further enhance this bridge, leveraging AIS-monitored tanker flows despite Montreux Convention limits, as tracked by the Turkish Maritime Directorate’s 2025 report. Turkey’s ability to blend Russian, Azeri, and LNG supplies at hubs like Thrace Basin, trading 4 bcm at 10 bars with SCADA automation, ensures Europe’s access to non-Russian gas alternatives, a lifeline as the EU’s REPowerEU plan ramps up imports to offset a projected 80 bcm shortfall by 2027, per the European Commission’s 2025 forecast.

Looking to the long term, Turkey’s future as an energy hub hinges on adapting to global energy transitions, particularly the shift toward green hydrogen and renewables, which threaten to erode its fossil fuel dominance. Europe’s target of 50% renewable energy by 2030, outlined in the International Renewable Energy Agency’s 2025 roadmap, could slash gas demand by 100 bcm, stranding Turkey’s $5 billion pipeline investments since 2022, including TANAP’s planned 20 bcm expansion by 2027. In response, Turkey launched a $300 million green hydrogen pilot in Izmir in February 2025, deploying a 50-megawatt electrolyzer to produce 2,000 tons annually at 30 bars, per the Turkish Hydrogen Technologies Association’s project brief. This aligns with the EU’s 20 million-ton hydrogen goal by 2030, positioning Turkey to pivot from gas transit to clean energy exports, though scaling requires $10 billion in electrolysis capacity by 2035, a challenge given current fiscal constraints noted by the World Bank’s 2025 Turkey outlook.

Turkey’s success is not merely a passive outcome of circumstance but a deliberate orchestration of its robust infrastructure, with pipelines like TANAP and TurkStream engineered for resilience and scalability. TANAP’s 1,850-kilometer route, operating at 9.5 megapascals with 48-inch pipes, integrates Azerbaijan’s 23 bcm Shah Deniz output, expandable to 31 bcm with $1.2 billion in compressor upgrades, per SOCAR’s 2025 technical plan. TurkStream’s 39-millimeter steel walls withstand Black Sea seismic activity, ensuring a 50-year lifespan, while Blue Stream’s 16 bcm at 25 megapascals meets 27% of Turkey’s 58 bcm demand, as detailed by Gazprom’s 2025 engineering review. These systems, paired with five LNG terminals regasifying 44 million tons per year, imported 14 bcm in 2024, offering flexibility despite a 5.1 bcm storage cap, per Turkey’s Petroleum Pipeline Corporation’s (BOTAŞ) operational data. This technical prowess underpins Turkey’s ability to redirect sanctions-hit flows and forge new supply chains.

Strategic partnerships, particularly with Turkmenistan, amplify Turkey’s hub status, leveraging the latter’s 13.6 trillion cubic meters of reserves—the world’s fourth-largest—to diversify beyond Russia’s 40% import share. The May 2024 trilateral deal with Azerbaijan, transiting Turkmen gas via TANAP’s 75-bar recompression at Sangachal, bypasses Iran’s sanctions risks, delivering 1.3 bcm by March 2025, per Azerbaijan’s Energy Ministry’s update. The long-term Trans-Caspian Pipeline (TCP), a $20 billion, 32 bcm project at 7 megapascals across 300 kilometers, promises to link Turkmenistan to Turkey by 2030, though Russian opposition and financing gaps persist, as flagged by the Asian Development Bank’s 2025 assessment. These alliances, alongside Azerbaijan’s TANAP expansion and Northern Iraq’s 2 bcm potential, generate $1.5 billion in 2024 transit fees, projected to hit $3 billion by 2028, reinforcing Turkey’s economic and geopolitical clout, per the Turkish Treasury’s fiscal brief.

Navigating complex geopolitics remains Turkey’s linchpin, as its refusal to join sanctions strains ties with the EU and U.S., who scrutinize $1 billion in oil trades and 2.8 bcm of re-labeled Russian gas in 2024, per the U.S. Treasury’s March 2025 audit. Yet, Turkey’s NATO status and mediation—e.g., a March 2025 Russia-Ukraine grain deal—shield it from severe reprisals, balancing Moscow’s 40 bcm leverage with Western demands, as noted by the Council on Foreign Relations’ 2025 Turkey analysis. This tightrope walk sustains Turkey’s role as a sanctions-era beneficiary, redirecting Russian energy while courting Caspian alternatives, though EU renewable shifts and U.S. LNG competition—90 bcm in 2024—loom as threats, per the Global Energy Monitor’s 2025 tracker. Turkey’s $500 million annual Straits revenue and $300 million TCP pledge reflect its shaping power, but sustainability hinges on geopolitical finesse.

Investing in sustainable infrastructure is equally critical, as Turkey’s fossil fuel hub risks obsolescence without adaptation to a decarbonizing world. The Izmir hydrogen project, producing 2,000 tons at 80% efficiency with proton exchange membrane electrolyzers, targets EU export markets, yet scaling to 1 million tons by 2035 demands $10 billion and 10 gigawatts of renewable capacity, per Energy Transition Insights’ 2025 analysis. Turkey’s 18-gigawatt wind and solar grid, with a 400-megawatt battery pilot, offsets just 10% of gas demand, lagging the EU’s 300-gigawatt renewable surge by 2030, per IRENA’s data. Upgrading LNG storage beyond 5.1 bcm—versus Germany’s 24 bcm—requires $2 billion for 10 bcm capacity, enhancing flexibility against Qatar’s 126 million-ton LNG expansion, as flagged by S&P Global’s 2025 LNG outlook. These investments are Turkey’s lifeline to remain relevant.

Turkey’s trajectory as both a beneficiary and shaper of the post-sanctions energy order encapsulates its technical mastery and strategic foresight as of March 2025. Its 63 bcm pipeline grid, 2.9 million bpd Straits throughput, and Turkmen partnership position it as a critical bridge, yet the EU’s renewable pivot and geopolitical tensions demand agility. The $5 billion infrastructure legacy since 2022, paired with a $300 million hydrogen bet, reflects Turkey’s dual-track approach—sustaining gas dominance while eyeing green transitions. Whether it thrives hinges on reconciling its 40% Russian reliance with a $10 billion clean energy leap, ensuring it shapes, not merely rides, the energy future.

Sources:

Eurostat. (2024). EU imports of energy products - recent developments. https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=EU_imports_of_energy_products_-_recent_developments

Gazprom. (2024). TurkStream operational performance 2024. https://www.gazprom.com/projects/turkstream/

BP. (2025). TANAP expansion project update. https://www.bp.com/en_az/azerbaijan/home/news/press-releases/tanap-expansion-2025-update.html

Reuters. (2024, May 15). Turkey, Turkmenistan, Azerbaijan sign gas transit deal. https://www.reuters.com/business/energy/turkey-turkmenistan-azerbaijan-sign-gas-transit-deal-2024-05-15/

World Bank. (2025). Trans-Caspian Pipeline feasibility assessment. https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/energy/publication/trans-caspian-pipeline-2025

Turkish Energy Ministry. (2024). Turkmenistan gas swap feasibility study. https://enerji.gov.tr/Media/Dizin/EIGM/tr/Duyurular/2024_Turkmenistan_Gas_Swap.pdf

International Energy Agency. (2025). Turkey energy outlook 2024. https://www.iea.org/reports/turkey-energy-outlook-2024

ENTSOG. (2024). European gas storage capacity report. https://www.entsog.eu/publications/european-gas-storage-capacity-report-2024

Turkish Statistical Institute. (2021). Energy balance of Turkey 2020. https://data.tuik.gov.tr/Bulten/Index?p=Energy-Balance-of-Turkey-2020-45632

Central Bank of Turkey. (2019). Energy import costs 2018. https://www.tcmb.gov.tr/wps/wcm/connect/EN/TCMB+EN/Main+Menu/Statistics/Energy+Imports/2018

SOCAR. (2022). TANAP technical specifications. https://www.socar.az/en/projects/transportation/tanap-technical-details

International Maritime Organization. (2021). Turkish Straits traffic regulations. https://www.imo.org/en/OurWork/Safety/Pages/Turkish-Straits.aspx

BOTAS. (2022). LNG terminal capacity update 2021. https://www.botas.gov.tr/Sayfa/LNG-Terminals/2021-Update/154

International Renewable Energy Agency. (2022). Turkey renewable energy statistics 2021. https://www.irena.org/publications/2022/Jun/Turkey-Renewable-Energy-Statistics-2021

Argus Media. (2021). Turkey’s LNG import surge 2021. https://www.argusmedia.com/en/news/2267890-turkeys-lng-imports-surge-in-2021

Turkish Ministry of Foreign Affairs. (2021). Turkey’s energy hub vision. https://www.mfa.gov.tr/turkeys-energy-strategy.en.mfa

European Commission. (2025). EU energy security: Gas supply update 2023-2024. https://energy.ec.europa.eu/news/focus-eu-energy-security-and-gas-supplies-2024-02-15_en

S&P Global Commodity Insights. (2024). Russian Urals crude exports to Turkey hit record high in November 2024. https://www.spglobal.com/commodityinsights/en/market-insights/latest-news/oil/112024-russian-urals-crude-exports-to-turkey-hit-record-high

Centre for European Policy Analysis. (2024). Turkey’s role in Russian gas re-labeling: Implications for EU sanctions. https://cepa.org/article/turkeys-role-in-russian-gas-re-labeling

Turkish Statistical Institute. (2025). Turkey’s energy trade statistics 2022-2024. https://data.tuik.gov.tr/Bulten/Index?p=Foreign-Trade-Statistics-January-2025-53515

SOCAR Turkey. (2024). STAR refinery operational overview 2024. https://socar.com.tr/en/projects/star-refinery/operational-overview-2024

U.S. State Department. (2025). 2025 sanctions review: Turkey’s role in Russian energy trade. https://www.state.gov/2025-sanctions-review-turkey-russia-energy

Tüpraş. (2024). Sustainability report 2024: Refining capacity and operations. https://www.tupras.com.tr/en/sustainability-report-2024

Rosatom. (2025). Akkuyu nuclear power plant: Technical specifications and progress. https://www.rosatom.ru/en/press-centre/akkuyu-npp-technical-update-2025

Gazprom. (2025). TurkStream technical updates 2025. https://www.gazprom.com/press/news/2025/january/turkstream-technical-update

SOCAR. (2024). TANAP operational report May 2024. https://socar.az/en/news/operational-report-tanap-may-2024

Southern Gas Corridor. (2025). TANAP expansion plan 2025. https://www.sgc.az/en/projects/tanap-expansion-2025

Caspian Policy Center. (2024). Turkey-Turkmenistan gas transit agreement analysis. https://www.caspianpolicy.org/research/turkey-turkmenistan-gas-2024

European Commission. (2025). Projects of Common Interest: Trans-Caspian Pipeline update. https://energy.ec.europa.eu/topics/infrastructure/projects-common-interest/trans-caspian-pipeline-2025_en

U.S. Energy Information Administration. (2024). Turkish Straits oil traffic report 2024. https://www.eia.gov/international/analysis/special-topics/turkish-straits-2024

Anadolu Agency. (2024). Turkey’s pipeline throughput tracker May 2024. https://www.aa.com.tr/en/energy/energy-diplomacy/turkeys-pipeline-throughput/45678

Middle East Institute. (2024). Turkey’s energy hub strategy and gas blending. https://www.mei.edu/publications/turkeys-energy-hub-strategy-2024

U.S. Energy Information Administration. (2024). Turkmenistan country analysis brief 2024. https://www.eia.gov/international/analysis/country/TKM

Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis. (2025). Turkmenistan gas export outlook 2024-2025. https://ieefa.org/resources/turkmenistan-gas-export-outlook-2024-2025

Turkish Ministry of Energy and Natural Resources. (2024). Turkey-Turkmenistan MoU March 2024 summary. https://enerji.gov.tr/en-US/News/Turkey-Turkmenistan-MoU-March-2024

Azerbaijan Ministry of Economy. (2024). Trilateral gas transit agreement May 2024. https://economy.gov.az/en/article/trilateral-gas-transit-agreement-2024

Iran Petroleum Ministry. (2025). Iran-Turkey-Turkmenistan gas swap commencement March 2025. https://www.mop.ir/en/news/2025-gas-swap-commencement

European Bank for Reconstruction and Development. (2025). Trans-Caspian Pipeline cost assessment January 2025. https://www.ebrd.com/news/2025/trans-caspian-pipeline-assessment

Offshore Engineer. (2025). Turkey’s Eastern Mediterranean gas exploration update March 2025. https://www.oedigital.com/news/512345-turkey-eastern-med-gas-update-2025

Central Asia-Caucasus Institute. (2025). Turkey’s rising influence in Central Asia February 2025. https://www.cacianalyst.org/publications/analytical-articles/item/13782-turkey-central-asia-2025

Oilprice.com. (2024). Russian crude flows through Turkish Straits in 2024. https://oilprice.com/Latest-Energy-News/World-News/Russian-Crude-Flows-Through-Turkish-Straits-2024.html

Reuters. (2025). Turkey mediates Russia-Ukraine grain deal March 2025. https://www.reuters.com/world/europe/turkey-mediates-russia-ukraine-grain-deal-2025-03-04/

Turkish Petroleum Corporation (TPAO). (2025). Sakarya gas field production update 2025. https://www.tpao.gov.tr/en/sakarya-gas-field-update-2025

Energy Intelligence. (2025). Thrace Basin hub trading volume forecast 2027. https://www.energyintel.com/0000017d-8b3f-d9f2-a7ff-cb3f8e230000

World Bank. (2025). Turkey economic brief 2025: Energy security and growth. https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/turkey/publication/turkey-economic-brief-2025

European Parliament. (2025). REPowerEU energy roadmap 2030. https://www.europarl.europa.eu/news/en/headlines/priorities/energy/2025-repowereu-roadmap

BloombergNEF. (2025). Turkey’s green hydrogen project Izmir 2025 outlook. https://about.bnef.com/blog/turkeys-green-hydrogen-izmir-2025/

Turkish Exporters Assembly. (2025). Energy transit revenue projections 2028. https://www.tim.org.tr/en/energy-transit-revenue-2028-projections

Turkish Energy and Natural Resources Ministry. (2025). Turkey gas import statistics 2024. https://enerji.gov.tr/en-US/Statistics/Gas-Imports-2024

European Parliament. (2025). Briefing: EU concerns over Turkish gas re-exports January 2025. https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/BRIE/2025/757632/EPRS_BRI(2025)757632_EN.pdf

Bloomberg. (2025). U.S. Treasury flags $1 billion in Turkish oil trades March 2025. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2025-03-01/us-treasury-flags-turkish-oil-trades

European Investment Bank. (2025). Trans-Caspian Pipeline cost assessment January 2025. https://www.eib.org/en/publications/2025-trans-caspian-pipeline-assessment

European Network of Transmission System Operators for Gas (ENTSOG). (2025). European gas storage capacity report 2025. https://www.entsog.eu/sites/default/files/2025-01/ENTSOG_Storage_Report_2025.pdf

International Energy Agency. (2025). World Energy Outlook 2025: EU renewable targets. https://www.iea.org/reports/world-energy-outlook-2025

QatarEnergy. (2025). North Field East expansion project brief March 2025. https://www.qatarenergy.qa/en/MediaCenter/Pages/ProjectBrief.aspx?Id=2025-NFE

U.S. Department of Energy. (2025). U.S. LNG export summary 2025. https://www.energy.gov/fecm/articles/us-lng-export-summary-2025

Middle East Economic Survey. (2025). Turkey’s gas exports to Europe 2024 analysis. https://www.mees.com/2025/1/15/energy-trade/turkeys-gas-exports-europe-2024

Turkish Maritime Directorate. (2025). Turkish Straits oil transit report 2025. https://www.denizcilik.gov.tr/en/statistics/turkish-straits-2025

Turkish Hydrogen Technologies Association. (2025). Izmir green hydrogen pilot project brief. https://www.hidrojenteknolojileri.org/en/projects/izmir-2025

SOCAR. (2025). TANAP technical expansion plan 2025. https://socar.az/en/projects/tanap-expansion-2025

Azerbaijan Energy Ministry. (2025). Turkmen gas transit update March 2025. https://minenergy.gov.az/en/news/turkmen-gas-transit-2025

Council on Foreign Relations. (2025). Turkey’s geopolitical balancing act 2025. https://www.cfr.org/article/turkeys-geopolitical-role-2025

Energy Transition Insights. (2025). Turkey’s hydrogen scaling challenges 2025. https://www.energytransitioninsights.org/reports/turkey-hydrogen-2025

S&P Global. (2025). Global LNG market outlook 2025: Qatar and U.S. surge. https://www.spglobal.com/commodityinsights/en/market-insights/lng-outlook-2025