Introduction

As global economic dynamics shift, businesses and policymakers are increasingly scrutinizing their reliance on China for manufacturing and trade. Rising labor costs, geopolitical tensions, and supply chain vulnerabilities have prompted companies to explore alternatives. Vietnam, a rapidly industrializing nation in Southeast Asia, has emerged as a viable option, often dubbed a "low-rent China." But is Vietnam merely a smaller-scale imitator of its northern neighbor, or does it offer unique advantages that align with global strategic needs?

To answer this, we must examine Vietnam's geographical, economic, and demographic landscape and its industrial, labor, and trade capacities. Vietnam's ascent as a manufacturing hub has been driven by competitive labor costs, strategic trade agreements, and significant foreign direct investment. Yet, challenges such as infrastructure limitations, environmental concerns, and regulatory hurdles persist, raising questions about its long-term competitiveness.

This discussion delves into Vietnam's potential to solve America's "China problem," evaluating its role as an emerging global player and comparing it with other strategic alternatives, including Mexico. From the geopolitical implications of decoupling to the practical considerations of trade, tariffs, and workforce dynamics, we explore whether Vietnam is a strategic solution or simply another iteration of China's mercantile model.

Location. Location. Location.

Vietnam is a Southeast Asian country located on the eastern edge of the Indochinese Peninsula. It stretches along the South China Sea, with its coastline forming a long, narrow strip of land that extends over 3,444 kilometers. To the north, Vietnam shares a border with China, which runs along the Beibu Gulf, also known as the Gulf of Tonkin. To the west, Vietnam is bordered by Laos and Cambodia, with the Mekong River serving as part of the natural frontier with Cambodia. The country's landscape is diverse, featuring the Red River Delta in the north, the Central Highlands, and the Mekong Delta in the south. Hanoi, the capital, is situated in the northern part of the country, while Ho Chi Minh City, the largest city and economic hub, is in the south. This geographic positioning places Vietnam at a strategic crossroads of maritime trade routes in Southeast Asia, influencing its historical, cultural, and economic interactions with both mainland Southeast Asia and the broader East Asian region.

General Economic Conditions of Modern Vietnam

Vietnam's current economic environment is one of dynamic growth and transformation. The nation has transitioned from a centrally planned economy to a more market-oriented system since the introduction of economic reforms known as "Doi Moi" in 1986. This shift has positioned Vietnam as one of the fastest-growing economies in Southeast Asia, with consistent GDP growth rates often surpassing 6% annually. Recent data indicates that Vietnam's GDP growth slowed to approximately 5% in 2024, reflecting global economic headwinds and domestic challenges, though projections suggest a recovery towards 5.8% in the same year.

The economy is characterized by a strong manufacturing sector, particularly in textiles, electronics, and increasingly, automotive industries, with significant foreign direct investment (FDI) from countries like the US, Japan, South Korea, and increasingly China. Vietnam has become a focal point for companies looking to diversify their manufacturing bases away from China, thanks to its competitive labor costs, strategic location, and trade agreements like the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) and the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP).

Despite these positive aspects, Vietnam faces several challenges. Inflation has been kept in check, generally below 4.5%, but the country struggles with issues like corruption, a weak legal framework for business, and environmental concerns. The dominance of state-owned enterprises in key sectors sometimes limits competition and innovation. The government has been actively working on reforms to encourage private sector growth, including revising laws related to investment, securities, and labor to attract high-tech industries and ensure better environmental standards.

Moreover, Vietnam's economic strategy continues to focus on sustainable and inclusive growth. Efforts are being made to move up the value chain, from labor-intensive manufacturing to higher-value-added industries and services. However, the country also faces external risks like global trade tensions, fluctuating commodity prices, and climate change impacts, which could disrupt its growth trajectory. Overall, Vietnam's economic environment is one of opportunity mixed with the need for ongoing reform and adaptation to global economic shifts.

Labor Cost Advantages

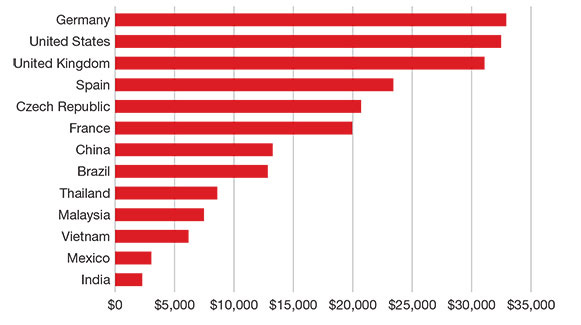

Vietnam's labor costs are generally lower than those in China, making it an attractive destination for manufacturing and other labor-intensive industries. Recent data suggests that the hourly wage for manufacturing in Vietnam is around $2.99, significantly less than China's, which stands at approximately $6.50 per hour. This disparity is one of the primary reasons why many multinational companies have been shifting their production bases from China to Vietnam, especially in sectors like textiles, footwear, electronics, and furniture.

However, it's important to note that labor costs in both countries have been on an upward trajectory. In Vietnam, wages have been increasing as the economy grows and the government raises the minimum wage to improve living standards. Despite this, Vietnam's wages still remain competitive compared to China, where labor costs have escalated due to higher living standards, an aging population, and government policies aimed at transitioning to higher value-added industries.

The comparison isn't just about the nominal cost; productivity levels also play a role. While Vietnamese labor might be cheaper, the productivity per worker can sometimes lag behind that of China due to differences in education, skill levels, and infrastructure. Nevertheless, Vietnam has been making strides to improve its workforce's skill set through vocational training and education reforms, aiming to close this gap.

In summary, while Vietnam's labor costs are lower than China's, the gap is narrowing as both countries undergo economic evolution. Vietnam leverages its lower labor costs as part of its appeal to foreign investors, but it must continue to enhance worker skills and productivity to maintain this competitive edge in the global market.

Industrial Capacity, Infrastructure, Stable Energy and Deep Water Ports

Vietnam has developed significant industrial capacity over recent decades, particularly in manufacturing sectors such as electronics, textiles, and automotive industries. This growth is supported by a large and relatively young workforce, which has attracted substantial foreign direct investment. The country's industrial zones, especially in areas like Ho Chi Minh City, Hanoi, and Da Nang, are hubs for both domestic and international businesses, enhancing its industrial capabilities.

In terms of infrastructure, Vietnam has been investing heavily to support its industrialization and urbanization. The government has prioritized the development of road networks, railways, airports, and ports. However, while urban centers and key economic zones have seen significant improvements, rural and less developed areas still lag behind, presenting a mixed picture of infrastructure quality across the country. Projects like the North-South Expressway and various urban rail systems in major cities illustrate ongoing efforts to expand and modernize infrastructure.

Regarding energy, Vietnam has been working towards ensuring a stable supply, although it faces challenges. The country relies heavily on coal for power generation, accounting for a significant portion of its electricity, which raises environmental concerns. However, there's a strategic push towards diversifying energy sources, with an increase in renewable energy projects, particularly solar and wind, alongside investments in hydropower and natural gas. The Power Development Plan 8 (PDP8) outlines ambitions to triple wind and double solar capacity by 2030, aiming for a more stable and sustainable energy mix.

Vietnam also boasts several deep-water ports, crucial for its role in international trade. Ports like Cai Mep-Thi Vai in the south can handle some of the world's largest container ships, providing direct access to major markets without the need for transshipment. Other notable deep-water facilities include Hai Phong's Lach Huyen port in the north, which has been upgraded to accommodate larger vessels, and the developing port of Van Phong in the central region. These ports are part of Vietnam's strategy to enhance its maritime trade capabilities, although continuous investment is needed to manage increasing cargo volumes and to meet international standards for efficiency and environmental sustainability.

Overall, Vietnam has made considerable strides in building industrial capacity, infrastructure, ensuring energy stability, and developing deep-water ports, but there are ongoing challenges that need to be addressed to sustain and expand these capabilities further.

Total Fertility Rate Trends and Demographics

Vietnam's Total Fertility Rate (TFR) has undergone significant changes over recent decades, reflecting broader socio-economic transformations. Historically, Vietnam had one of the highest fertility rates in the world, with rates above 6 children per woman in the early 1970s. However, following the introduction of the "Doi Moi" economic reforms in 1986 and the government's two-child policy, the TFR began to decline dramatically. By 1999, the rate had dropped to 2.3 children per woman, nearing the replacement level fertility rate of 2.1, which is the average number of children per woman needed for a population to replace itself without migration.

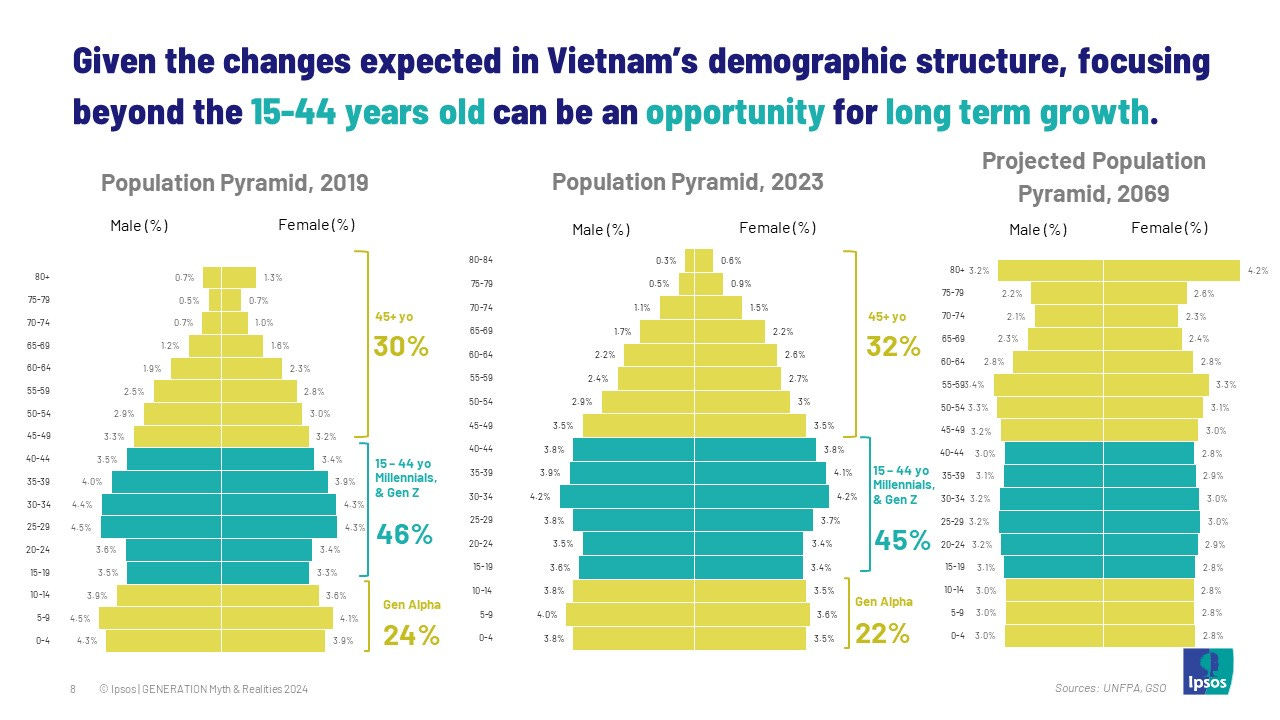

Recent trends show that Vietnam's TFR has continued to decrease, reaching 1.941 in 2022, according to World Bank data, which is below the replacement level. This decline has been more pronounced in urban areas, where the fertility rate has fallen below 1.7 children per woman in recent years, compared to rural areas where rates were slightly higher but also under the replacement level. The eastern parts of southern Vietnam, including Ho Chi Minh City, and the Mekong Delta have particularly low rates, with some regions reporting rates as low as 1.5 children per woman.

This trend towards lower fertility rates is part of a broader global pattern but is happening at a faster pace in Vietnam. Factors contributing to this include increased education levels, particularly for women, higher urbanization rates, a shift towards later marriages, and greater participation of women in the workforce. Additionally, access to contraception and family planning services, which have been heavily promoted by the Vietnamese government, has played a significant role in this demographic shift.

Demographically, Vietnam is experiencing an aging population as a result of these lower birth rates combined with increasing life expectancy. The median age in Vietnam has risen to 32.9 years in 2024, and projections suggest that by 2069, there could be three elderly people for every two children, signaling potential future challenges in terms of social welfare, healthcare, and labor force sustainability. The population pyramid is transitioning from an expansive shape to a more constrictive one, indicating fewer young people entering the workforce to support an aging population. This demographic transition necessitates policy adjustments in areas like retirement age, healthcare, and economic planning to mitigate the impacts of an aging society.

NEET Rate

The Vietnamese NEET (Not in Education, Employment, or Training) rate, which refers to the percentage of young people who are not engaged in education, employment, or training, provides insight into the youth labor market and social dynamics. While specific, recent, and comprehensive data on Vietnam's NEET rate compared directly to international cohorts is not readily available, we can infer from general trends and available data points.

In Vietnam, the NEET rate has been a concern, particularly in the context of an economy striving to transition from labor-intensive to more skilled and service-based industries. Data from around the early 2020s suggested that Vietnam's NEET rates were relatively low compared to some other Southeast Asian countries and certain European nations, but still significant enough to warrant attention. For instance, in 2022, Vietnam's multidimensional poverty rate was 5.71%, which indirectly indicates the socio-economic backdrop against which NEET rates might be considered.

Comparatively, in the European Union, the NEET rate for young people aged 15-29 was around 11.7% in 2022, with significant variations among member states. Countries like Romania had higher rates, while nations like the Netherlands had much lower ones, reflecting diverse economic conditions, educational policies, and labor market dynamics. In contrast, Vietnam's situation is unique due to its rapid economic growth and the transformation of its labor market. However, the exact figures for Vietnam's NEET rate can vary due to different age groups considered, the rural-urban divide, and the inclusion of informal employment in statistics.

Vietnam's focus on education and vocational training, alongside economic growth, has generally kept NEET rates lower than in many developed countries where youth might have access to welfare benefits allowing them to remain NEET longer. Nonetheless, challenges remain, particularly in ensuring equitable access to education and employment opportunities across different regions and socio-economic groups. The emphasis on reducing the NEET rate in Vietnam is part of broader efforts to harness the demographic dividend of a young population by integrating them into the workforce or further education, thereby preventing long-term social and economic exclusion.

Rural v Urban Population

Vietnam's rural areas have historically provided a significant labor pool for urban manufacturing sectors, but whether there are "enough" people depends on several factors including demographic trends, economic conditions, and migration patterns. The country has been experiencing rural-to-urban migration for decades, driven by job opportunities in urban areas, particularly in manufacturing and services. This migration has been crucial for the growth of Vietnam's industrial sectors, especially in regions like the Mekong Delta, the Red River Delta, and around Ho Chi Minh City.

Demographically, Vietnam is at a point where its population is still young, with a median age of about 32.9 years in 2024. However, the Total Fertility Rate has dropped below the replacement level, suggesting that the pool of young workers from rural areas might not grow as quickly in the future. Despite this, there remains a substantial number of people in rural areas, with agriculture still employing a significant portion of the population, though this is decreasing as more individuals seek non-agricultural employment.

The capacity of rural areas to supply urban manufacturing sectors with workers also hinges on the absorption capacity of urban centers. Vietnam has seen considerable foreign direct investment (FDI) in manufacturing, particularly in sectors like electronics, textiles, and automotive, which have created numerous jobs. However, the influx of new businesses could strain this supply of labor if not managed carefully. Factors like the skill level of rural migrants, urban infrastructure to accommodate population growth, and the speed at which new jobs are created compared to the natural increase and migration rates are critical.

Moreover, while there is a potential labor pool in rural Vietnam, not all rural workers are immediately suitable for urban manufacturing jobs without some form of skill development or training. The government has been promoting vocational training to bridge this gap, but there remains a challenge in ensuring that this training is accessible and relevant to the needs of urban industries. Additionally, the quality of life, wage expectations, and the pull of urban amenities versus rural life also influence migration decisions. If new businesses can offer attractive employment conditions, there is likely still a significant untapped labor force in rural Vietnam eager to move to urban areas for better prospects. However, long-term sustainability will require addressing demographic shifts, enhancing rural education, and improving urban planning to accommodate growth.

Education Trends in Vietnam

Vietnam has been making significant strides in fostering a technically educated citizenry, driven by its ambition to transition from a labor-intensive economy to one based on knowledge and innovation. The country's education system, which is state-run and managed by the Ministry of Education and Training, has increasingly focused on STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, Mathematics) education. In recent years, there's been a notable push towards improving both the quantity and quality of technical education from primary through to higher education levels.

In higher education, Vietnam has seen a surge in the number of students pursuing technical fields. The number of students enrolled in institutions of higher education grew dramatically, from about 133,000 in 1987 to over 2 million by 2015, with a significant portion now engaged in technical and science-related courses. Universities like Hanoi University of Science and Technology and the Ho Chi Minh City University of Technology are among the institutions that have become well-known for producing technically competent graduates. Additionally, Vietnam's participation in international assessments like PISA has highlighted its students' strong performance in mathematics and science, suggesting a solid foundation in technical education at earlier stages.

The government has also recognized the need for vocational and technical training to meet the demands of the labor market. Vocational education and training (VET) programs have been expanded, with both the Ministry of Education and Training and the Ministry of Labor, Invalids and Social Affairs overseeing various programs that range from short-term training to comprehensive vocational education. These initiatives aim to equip young Vietnamese with practical skills that are directly applicable to industries like manufacturing, IT, and construction, which are critical for economic development.

However, despite these advancements, challenges remain. There's a noted disparity in educational quality between urban and rural areas, and the educational curriculum has sometimes been criticized for being too rigid or not fully aligned with industry needs. Efforts to increase the autonomy of higher education institutions and reform curricula are ongoing, aiming to create a more dynamic and responsive educational system. Moreover, while Vietnam has a growing number of technically educated citizens, there's still a gap in providing high-level, specialized skills that meet the evolving demands of global high-tech industries. This is where partnerships with foreign universities, increased international student mobility, and investment in R&D play crucial roles in further elevating the technical expertise of its citizenry.

Overall, Vietnam is actively working towards enhancing its technically educated population, with policies and investments that reflect a recognition of the importance of technical skills for economic competitiveness. Still, continuous improvement in educational quality, industry alignment, and equitable access to education across all regions are necessary to fully realize this potential.

Trade with the US

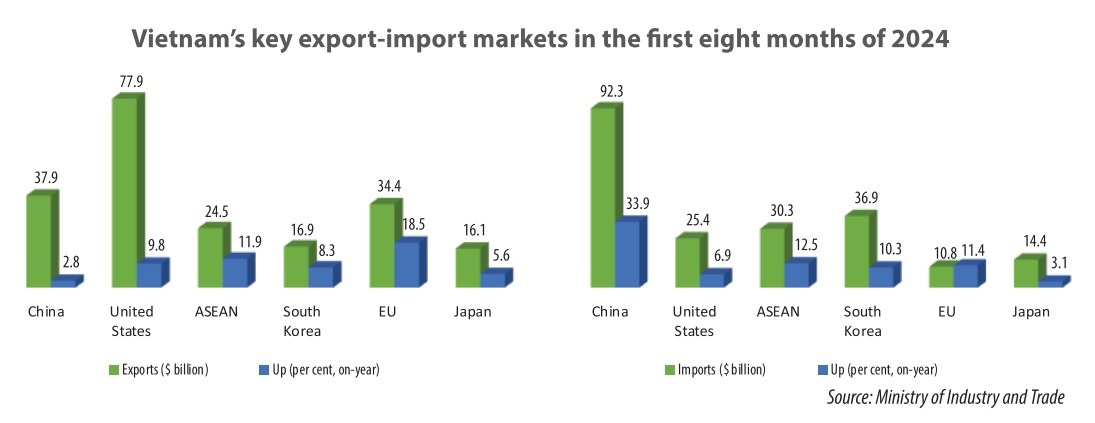

Vietnam does export a significant amount of goods to the United States, with the relationship having grown substantially since the normalization of diplomatic relations in the 1990s. In 2022, Vietnam's exports to the United States totaled approximately $117 billion, making the US one of Vietnam's largest export markets. These exports include a wide range of products, with electronics, textiles, footwear, furniture, and seafood being among the top items.

Regarding the trade balance, Vietnam has consistently maintained a trade surplus with the United States. This surplus was notably high in recent years; in 2022, Vietnam's trade surplus with the US was about $104.6 billion. This figure reflects the significant growth in Vietnamese exports to the US, which has outpaced the increase in US exports to Vietnam. The US exports to Vietnam, while growing, are considerably less, focusing on items like raw materials, machinery, and agricultural products, amounting to roughly $11.4 billion in 2022.

This trade surplus has been a point of discussion, particularly in the context of US trade policy. During the Trump administration, Vietnam faced scrutiny over its trade practices due to this surplus, with some officials alleging currency manipulation, though these claims were not substantiated in formal investigations. The trade relationship has been characterized by concerns over intellectual property rights, labor standards, and the environmental impact of rapid industrial growth in Vietnam. Despite these issues, the trade relationship remains robust, supported by various free trade agreements and Vietnam's strategic importance in diversifying supply chains away from other regions like China.

The ongoing trade dynamics show Vietnam's increasing role in global trade networks, with its economy benefiting from the demand for its manufactured goods in the US market. However, this surplus also places Vietnam under international economic scrutiny, particularly with the potential for trade policy changes from the US, especially as the global economic landscape evolves.

Firms Relocating to Vietnam

Several American firms have shown interest in relocating or expanding their operations to Vietnam, driven by factors like rising labor costs in China, the US-China trade tensions, and Vietnam's strategic advantages in terms of labor costs, trade agreements, and geographical location. Over the last several years, notable American companies have already made significant moves into Vietnam:

In the technology sector, Apple has increasingly shifted its manufacturing base to Vietnam. Suppliers like Foxconn, Pegatron, and Goertek have expanded their operations there, particularly for assembling products like AirPods and MacBooks. Intel has also been a major player, having invested over $1 billion in its assembly and test facility in Ho Chi Minh City, which is one of Intel's largest globally. Boeing has been working with Vietnamese suppliers, though mostly through intermediaries, with plans to potentially deepen direct partnerships.

In other industries, companies like Nike have long established manufacturing operations in Vietnam, leveraging its competitive labor market for footwear production. Coca-Cola and PepsiCo have expanded their bottling and distribution networks in the country, responding to the growing Vietnamese market and the strategic position for exports. The apparel sector has seen brands like Gap and Under Armour increase their sourcing from Vietnam.

Looking forward, there are indications that more American firms are planning or considering relocation to Vietnam. Nvidia has recently announced plans to partner with the Vietnamese government to establish an AI research and development center, with Viettel Group's data center supporting this initiative. This move is part of a broader Southeast Asian push for Nvidia, aiming to leverage Vietnam's growing tech landscape.

Additionally, sectors like healthcare and automotive are seeing interest from American companies. For instance, medical device and pharmaceutical companies are eyeing Vietnam for its potential in serving both domestic and regional markets. In automotive, there's interest from companies looking at Vietnam not just for assembly but also for parts manufacturing, given the growth in the local vehicle market and the advantages of trade agreements like the CPTPP.

However, the exact plans of companies can be subject to change due to various factors including global economic conditions, local regulations, and the ongoing assessment of Vietnam's business environment. While the trend towards Vietnam is clear, the specifics of which companies are in the planning phase can often be speculative until formal announcements are made.

Taking Advantage of Decoupling with China

Vietnam is strategically positioned to benefit from the global trend of "decoupling" from China, where companies seek to diversify their supply chains away from reliance on one country, particularly due to geopolitical tensions, trade wars, and the desire to mitigate risks associated with over-dependence on a single market. Several key factors make Vietnam an attractive alternative:

Geographically, Vietnam sits at the crossroads of Southeast Asia, offering direct access to major shipping lanes and proximity to both Asian and Western markets. This position not only reduces logistics costs but also facilitates faster shipping times compared to moving goods from the interior of China. Vietnam's long coastline with several deep-water ports like Cai Mep-Thi Vai and Lach Huyen enhances its capability to handle large volumes of international trade.

Economically, Vietnam has established itself as a manufacturing hub with lower labor costs compared to China, making it economically viable for companies to relocate operations. The presence of numerous industrial parks and special economic zones tailored for foreign investment further incentivizes businesses. The Vietnamese government has been proactive in offering tax breaks, land lease subsidies, and other investment incentives to attract multinational corporations. Vietnam's participation in various trade agreements, like the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP), the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), and its trade deal with the EU, provides access to markets with reduced or eliminated tariffs, enhancing its attractiveness as an export base.

In terms of industrial capacity, Vietnam has been developing its infrastructure to support a growing manufacturing sector. The country has seen significant investments in manufacturing, particularly in electronics, textiles, and automotive industries. Companies like Samsung, which has made Vietnam its largest production base outside South Korea, illustrate this shift. The focus on technical education and vocational training is also preparing a workforce that can meet the demands of more sophisticated manufacturing processes, although challenges in skill levels persist.

Politically, Vietnam's stability and its "bamboo diplomacy," which involves maintaining balanced relationships with both the US and China, provide a neutral ground for businesses wary of geopolitical risks. While Vietnam shares ideological ties with China, it also seeks to assert its sovereignty, especially in maritime disputes, which aligns with the strategic interests of countries looking to diversify away from China.

Finally, the environmental and regulatory framework in Vietnam, though still developing, is seen as more flexible and less stringent in some areas compared to China, particularly in terms of speed to market for new manufacturing setups. However, Vietnam must continue to address issues like environmental regulations, intellectual property rights, and corruption to fully capitalize on this opportunity.

In summary, Vietnam's strategic location, competitive labor market, supportive government policies, growing industrial infrastructure, and balanced international relations position it well to take advantage of strategic decoupling from China, although it must continue to enhance its capabilities and address existing challenges to remain a long-term attractive destination for global businesses.

Current Duties and Tariffs on Vietnam

Currently, there are duties and tariffs in place for goods imported from Vietnam into the United States. The United States applies tariffs based on the Harmonized Tariff Schedule (HTS), which categorizes goods into specific codes, each with its own duty rate. Vietnam does not have a free trade agreement with the US that eliminates all tariffs, although Vietnam benefits from "normal trade relations" status, which means it receives Most-Favored-Nation (MFN) tariff rates rather than higher, punitive tariffs.

For many goods, the MFN tariff rates are relatively low, often ranging from 0% to 25% depending on the product category. However, certain products can face higher tariffs due to various reasons, including anti-dumping duties or countervailing duties. For instance, in 2019, the US Commerce Department imposed duties of over 400% on specific types of steel from Vietnam, accusing some businesses of circumventing duties by processing materials from South Korea and Taiwan in Vietnam before exporting them to the US.

(Pictured Above: Hoa Phat Group (HPG) - The largest steel mill in Vietnam)

Additionally, there are specific tariffs on imports like solar panels and textiles. The US has implemented anti-dumping duties on solar products from Vietnam among other countries, with rates varying based on the investigation's findings, sometimes reaching up to 271% for certain imports. Textiles and apparel from Vietnam are also subject to tariffs, although the rates are generally lower, around 9% for clothing items, but can vary based on material composition and other factors.

Vietnam's participation in trade agreements like the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) does not directly benefit its trade with the US since the US withdrew from the original TPP. However, Vietnam's involvement in other agreements can indirectly affect its trade dynamics by improving its overall trade competitiveness.

The exact tariffs and duties can change due to ongoing trade reviews, new trade policies, or agreements, but as of now, Vietnam's exports to the US are subject to these tariffs, which vary by product, impacting the cost and competitiveness of Vietnamese goods in the US market.

Trump Tariffs

Donald Trump has not explicitly threatened Vietnam with new tariffs in statements following his election victory for his term starting in January 2025. However, during his previous term, there were actions and statements that suggest Vietnam could be a target for tariffs under his administration. In 2020, the Trump administration initiated investigations into Vietnam's currency practices and trade policies under Section 301 of the Trade Act of 1974, which could have led to tariffs if findings were unfavorable. While these investigations did not result in immediate tariffs, they set a precedent for future trade policy actions.

Recent analyses and reports from economic think tanks and media outlets indicate that Vietnam might face tariff threats if Trump pursues his campaign promises of imposing high tariffs on imports to reduce trade deficits. Vietnam has one of the largest trade surpluses with the US, which was over $100 billion in recent years, making it a potential target for tariff policies aimed at correcting what Trump views as trade imbalances. Trump's appointment of advisors like Peter Navarro, known for advocating for tariffs, further fuels speculation that Vietnam could be in the crosshairs.

Moreover, posts on social media have hinted at the possibility of Vietnam facing tariffs due to its trade surplus with the US. Industry executives and analysts have expressed concerns in various forums about how a second Trump administration might treat Vietnam, especially with Trump's focus on bilateral trade deficits. The rhetoric around trade during Trump's campaign included broad threats to impose tariffs on countries with significant trade surpluses with the US, which would include Vietnam.

While there's no direct, new threat from Trump regarding Vietnam tariffs for 2025, the context from his past administration, his campaign promises, and the general direction of his trade policy suggest that Vietnam might need to prepare for potential tariff impositions or at least for negotiations under the threat of tariffs. This situation remains fluid, with much depending on the specific policies Trump chooses to enact once in office and the outcome of any trade negotiations or reviews that might occur.

Is Vietnam just another low rent China?

The question of whether transitioning trade from China to Vietnam merely swaps one mercantile government for another is nuanced but valid. Both China and Vietnam operate under systems where the state plays a significant role in economic activities, including using mechanisms like currency devaluation, tariffs, and subsidies to influence trade outcomes. China has long been criticized by the US for these practices, especially in terms of currency manipulation to keep the yuan undervalued, thereby making Chinese exports cheaper and more competitive. Vietnam, while not as large or influential as China, has also faced allegations of similar practices, although on a smaller scale.

Vietnam's currency, the Vietnamese đồng, has been noted by some analysts for its managed depreciation, which can be seen as an indirect form of export subsidy by making Vietnamese goods less expensive in dollar terms. The US Treasury has periodically labeled Vietnam as a currency manipulator or placed it on a watch list for currency practices. However, unlike China, Vietnam's economic influence globally is less pervasive, which means its practices, while similar in nature, do not have the same impact on a global scale.

On tariffs and subsidies, Vietnam has also employed strategies to boost its export sectors. The government offers various incentives to foreign investors, including tax breaks, land-use rights, and infrastructure support, which can be seen as subsidies. These incentives are designed to attract manufacturing and high-tech industries, particularly in light of the US-China trade tensions. While these practices are not unique to Vietnam (many countries use similar strategies to attract FDI), they do align with mercantilist policies aimed at enhancing export competitiveness.

Vietnam's engagement in multiple free trade agreements (like CPTPP, RCEP) imposes some international oversight and pressure to adhere to trade norms, which might not be as stringent for China given its economic weight and strategic importance.

Critically, the transition from China to Vietnam also reflects broader geopolitical strategies, including diversifying supply chains to mitigate risks. While Vietnam might employ some of the same economic tactics as China, the scale, impact, and international response differ. The US and other nations might view Vietnam's actions through a different lens, partly because Vietnam's strategic alignment with Western interests, particularly in countering China's influence in Southeast Asia, could influence trade policies and diplomatic relations.

In summary, while Vietnam does exhibit some mercantilist behaviors akin to those of China, the scale, global impact, and international context are different. The transition represents not just an economic choice but a strategic one, where geopolitical considerations and the quest for supply chain resilience play significant roles alongside economic policies.

Vietnam or Mexico

When American companies consider decoupling from China, the choice between Vietnam and Mexico involves evaluating several key factors, each with its own set of advantages and challenges. Vietnam offers access to Asia, where proximity to other high-growth markets and established supply chains can be beneficial. Its labor costs are generally lower than in China, making it an attractive destination for labor-intensive manufacturing. Vietnam has been actively improving its infrastructure, including ports and industrial zones, to accommodate foreign investment. The country's participation in numerous trade agreements, like the CPTPP, provides advantageous tariff reductions and market access, enhancing its appeal for companies looking to export to multiple markets.

On the other hand, Mexico presents a compelling case with its geographical proximity to the United States, which significantly reduces shipping times and costs, especially important for just-in-time manufacturing models. The USMCA (United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement) further strengthens Mexico's position by providing duty-free access to North American markets, which is crucial for companies aiming to serve both the U.S. and Canadian markets efficiently. Mexico also has a more developed manufacturing base in sectors like automotive and electronics, with established supply chains that integrate well with U.S. industry needs. Additionally, labor costs in Mexico, while higher than in Vietnam, are still competitive when compared to U.S. wages and can be offset by savings in logistics and tariffs.

Cultural and language similarities between Mexico and the U.S. can ease business operations, reducing the learning curve for American companies. However, Mexico faces challenges like higher crime rates in some regions, which can affect business operations and security considerations. Vietnam, while culturally different, has shown a strong commitment to improving business environments, including legal reforms to protect intellectual property and encourage foreign investment.

Environmental regulations, labor laws, and political stability also play roles in decision-making. Vietnam is often perceived as having less stringent environmental regulations, which might attract companies looking for fewer compliance costs, though this is increasingly scrutinized by international standards. Mexico, with its more mature industrial sectors, has stricter environmental and labor standards but also benefits from being closer to U.S. regulatory oversight, which can be advantageous for compliance with American laws and consumer expectations.

Ultimately, the choice between Vietnam and Mexico might depend on the specific industry, the type of product being manufactured, and strategic corporate goals. For companies with a focus on electronics or textiles looking to leverage Asian supply chains, Vietnam might be preferable. Conversely, for those in automotive or other sectors where proximity to the U.S. market, cultural familiarity, and established North American supply chains are critical, Mexico could be the better choice. Some companies opt for a "China Plus One" strategy, using both Vietnam and Mexico to diversify risk and optimize supply chain resilience. This dual approach can leverage the strengths of each location while mitigating the risks associated with relying solely on one country.

Conclusion

Vietnam's emergence as an alternative to China highlights the complexities of shifting global trade dynamics. While Vietnam shares similarities with China in terms of state-driven economic policies—such as subsidies for key industries, managed currency devaluation to boost exports, and trade imbalances—it offers a unique opportunity for companies seeking to diversify their supply chains. These practices have made Vietnam a competitive player in global manufacturing.

Despite these parallels, Vietnam operates at a smaller scale and presents itself as a less dominant, more adaptable partner in international trade. Its strategic trade agreements, competitive labor costs, and improving industrial capacity give it an edge as a manufacturing hub. At the same time, Vietnam competes with Mexico for companies decoupling from China. While Mexico benefits from proximity to the United States, duty-free trade under the USMCA, and established supply chains, Vietnam's lower wages, access to Asian markets, and burgeoning infrastructure attract businesses looking for a foothold in Southeast Asia.

In the end, Vietnam is not a perfect replacement for China, nor is it free from challenges like infrastructure gaps, workforce development, and environmental concerns. However, it provides a potentially viable alternative for companies navigating the complexities of global trade. As Vietnam continues to develop its industrial base and address its structural issues, it remains a strategic option for those balancing the need to diversify from China with the opportunities presented by emerging markets. Whether as a complement to Mexico or as a standalone solution, Vietnam is poised to play a pivotal role in the evolving landscape of global supply chains.

Sources:

World Bank. (n.d.). Vietnam overview. World Bank. https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/vietnam/overview

Groupe Crédit Agricole. (n.d.). Vietnam economic overview. Groupe Crédit Agricole. https://international.groupecreditagricole.com/en/international-support/vietnam/economic-overview

Economist Intelligence Unit. (n.d.). Vietnam. EIU. https://country.eiu.com/vietnam

BNP Paribas. (2024, March 12). Vietnam: Wind in the sails. BNP Paribas Economic Research. https://economic-research.bnpparibas.com/html/en-US/Vietnam-wind-sails-2/13/2024,49349

Vietnam Briefing. (2023). Recap of Vietnam's economy in 2023. Vietnam Briefing. https://www.vietnam-briefing.com/news/recap-vietnams-economy-in-2023.html/

Lowy Institute. (2016). The missing middle: The political economy of economic restructuring in Vietnam. Lowy Institute. https://www.lowyinstitute.org/publications/missing-middle-political-economy-economic-restructuring-vietnam

Embassy of the Republic of Belarus in Vietnam. (n.d.). Export by Belarus to Vietnam. Embassy of the Republic of Belarus in Vietnam. https://vietnam.mfa.gov.by/en/exportby/business/viobzec/

U.S. Department of State. (2022). 2022 Investment climate statements: Vietnam. U.S. Department of State. https://www.state.gov/reports/2022-investment-climate-statements/vietnam/

Asian Development Bank. (n.d.). Vietnam: Economy. Asian Development Bank. https://www.adb.org/where-we-work/viet-nam/economy

International Monetary Fund. (n.d.). Vietnam: Raising millions out of poverty. IMF. https://www.imf.org/en/Countries/VNM/vietnam-raising-millions-out-of-poverty

Vietnam Briefing. (n.d.). Why manufacturing is driving Vietnam's growth. Vietnam Briefing. https://www.vietnam-briefing.com/news/why-manufacturing-is-driving-vietnams-growth.html/

Modern Materials Handling. (n.d.). Global labor rates: China is no longer a low-cost country. MMH. https://www.mmh.com/article/global_labor_rates_china_is_no_longer_a_low_cost_country

Cosmosourcing. (n.d.). China vs Vietnam manufacturing sourcing: Pros and cons. Cosmosourcing. https://www.cosmosourcing.com/blog/china-vs-vietnam-manufacturing-sourcing-pros-and-cons

Global Payroll Magazine. (2016, August/September). The minimum wage debate across China, India, and Vietnam. Global Payroll. https://global.payroll.org/publications-resources/Global-Payroll-Magazine/august-september-2016-issue/features-minimum-wage-debate-across-china-india-and-vietnam

Supply Chain Dive. (n.d.). Vietnam's rise as a manufacturing hub for semiconductors. Supply Chain Dive. https://www.supplychaindive.com/news/vietnam-manufacturing-semiconductors-hub-growth-us-biden-china-amkor-intel-google/700461/

SupplyIA. (n.d.). Manufacturing moving from China to Vietnam. SupplyIA. https://www.supplyia.com/manufacturing-moving-from-china-to-vietnam/

Statista. (n.d.). Manufacturing labor costs per hour - China, Vietnam, Mexico. Statista. https://www.statista.com/statistics/744071/manufacturing-labor-costs-per-hour-china-vietnam-mexico/

Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. (2020, June 18). Is Vietnam eating into China's share of manufacturing? Carnegie Endowment. https://carnegieendowment.org/2020/06/18/is-vietnam-eating-into-china-s-share-of-manufacturing-pub-82094

Wall Street Journal. (2019, August 20). For manufacturers in China, breaking up is hard to do. WSJ. https://www.wsj.com/articles/for-manufacturers-in-china-breaking-up-is-hard-to-do-11566397989

Forbes. (2017, June 7). Vietnam is losing ground to China because it lacks skilled workers. Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/ralphjennings/2017/06/07/vietnam-is-losing-ground-to-china-because-it-lacks-skilled-workers/

Avela. (n.d.). Is Vietnam the new China for manufacturing? Part 1. Avela. https://avela.com/is-vietnam-the-new-china-for-manufacturing-part-1/

Quartz. (2021, February 24). If China is no longer the world's factory, what will replace it? Quartz. https://qz.com/1953026/if-china-is-no-longer-the-worlds-factory-what-will-replace-it

The Diplomat. (2017, February 14). Which Asian country will replace China as the world's factory? The Diplomat. https://thediplomat.com/2017/02/which-asian-country-will-replace-china-as-the-worlds-factory/

U.S. Department of Commerce. (n.d.). Vietnam - power generation, transmission, and distribution. U.S. Department of Commerce. https://www.trade.gov/country-commercial-guides/vietnam-power-generation-transmission-and-distribution

Vietnam Briefing. (n.d.). Port infrastructure in Vietnam: 3 hubs for importers-exporters. Vietnam Briefing. https://www.vietnam-briefing.com/news/port-infrastructure-vietnam-3-hubs-for-importers-exporters.html/

Our World in Data. (n.d.). Energy in Vietnam. Our World in Data. https://ourworldindata.org/energy/country/vietnam

Statista. (n.d.). Vietnam: Leading sea ports by throughput. Statista. https://www.statista.com/statistics/1045072/vietnam-leading-sea-ports-by-throughput/

U.S. Department of Commerce. (n.d.). Vietnam - Energy sector. U.S. Department of Commerce. https://www.trade.gov/market-intelligence/vietnam-energy-sector

Vietnam Briefing. (n.d.). Why Vietnam's infrastructure is crucial for economic growth. Vietnam Briefing. https://www.vietnam-briefing.com/news/why-vietnams-infrastructure-crucial-for-economic-growth.html/

HP Toàn Cầu. (n.d.). List of seaports in Vietnam. HP Toàn Cầu. https://hptoancau.com/en/list-of-seaports-in-vietnam/

Marine Insight. (n.d.). 5 major ports of Vietnam. Marine Insight. https://www.marineinsight.com/know-more/5-major-ports-of-vietnam/

WHA Vietnam. (n.d.). Overview of infrastructure industry in Vietnam and notes on renting industrial zones. WHA Vietnam. https://www.whavietnam.com/news-articles/overview-of-infrastructure-industry-in-vietnam-and-notes-on-renting-industrial-zones-282-155.html

Financial Times. (2006, December 15). Vietnam's economic surge. Financial Times. https://www.ft.com/content/0f5e5b90-c51d-11db-b110-000b5df10621

IndexMundi. (n.d.). Vietnam - NEET rate. IndexMundi. https://www.indexmundi.com/facts/vietnam/indicator/SL.UEM.NEET.MA.ZS

World Education News + Reviews. (2017, November). Education in Vietnam. WENR. https://wenr.wes.org/2017/11/education-in-vietnam

Asia Society. (n.d.). Education in Vietnam. Asia Society. https://asiasociety.org/global-cities-education-network/education-vietnam

Scholaro. (n.d.). Education system in Vietnam. Scholaro. https://www.scholaro.com/db/Countries/Vietnam/Education-System

U.S. Census Bureau. (n.d.). U.S. trade in goods with Vietnam. U.S. Census Bureau. https://www.census.gov/foreign-trade/balance/c5520.html

General Statistics Office of Vietnam. (2023, July). Overcoming difficulties, Vietnam has a trade surplus of 12.25 billion USD in 6 months of 2023. GSO. https://www.gso.gov.vn/en/data-and-statistics/2023/07/overcoming-difficulties-vietnam-has-a-trade-surplus-of-12-25-billion-usd-in-6-months-of-2023/

Observatory of Economic Complexity. (n.d.). Vietnam (VNM) and United States (USA) trade. OEC. https://oec.world/en/profile/bilateral-country/usa/partner/vnm

U.S. International Trade Commission. (2019). Vietnam trade shifts. USITC. https://www.usitc.gov/research_and_analysis/trade_shifts_2019/vietnam.htm

U.S. Department of Commerce. (2022). 2022 Statistical analysis of U.S. trade with Vietnam. BIS. https://www.bis.doc.gov/index.php/country-papers/3429-2022-statistical-analysis-of-us-trade-with-vietnam/file

U.S. Department of Commerce. (n.d.). Exporting to Vietnam: Market overview. U.S. Department of Commerce. https://www.trade.gov/knowledge-product/exporting-vietnam-market-overview

Air University. (2023). US-Vietnam trade ties: Challenges ahead. JIPA. https://www.airuniversity.af.edu/JIPA/Display/Article/3344116/usvietnam-trade-ties-challenge-ahead/

U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis. (2023). U.S. international trade in goods and services - September 2023. BEA. https://www.bea.gov/news/2023/us-international-trade-goods-and-services-september-2023

Nasdaq. (n.d.). Vietnam posts record 2022 trade surplus with U.S. as China deficit rises. Nasdaq. https://www.nasdaq.com/articles/vietnam-posts-record-2022-trade-surplus-with-u.s.-as-china-deficit-rises

Radio Free Asia. (2024, November 8). Vietnam commentary: Trump's trade. RFA. https://www.rfa.org/english/opinions/2024/11/08/vietnam-commentary-trump-trade/

Vietnam Briefing. (n.d.). Relocating production to Vietnam for US businesses: What you need to know. Vietnam Briefing. https://www.vietnam-briefing.com/news/relocating-production-vietnam-for-us-businesses-what-you-need-to-know.html/

Vietnam Briefing. (n.d.). Why companies relocate to Vietnam. Vietnam Briefing. https://www.vietnam-briefing.com/doing-business-guide/vietnam/why-vietnam/why-companies-relocate-to-vietnam

Expat Arrivals. (n.d.). Relocation companies in Vietnam. Expat Arrivals. https://www.expatarrivals.com/asia-pacific/vietnam/relocation-companies-vietnam

Vietnam Briefing. (n.d.). Why Vietnam has become a promising alternative for US businesses in Asia. Vietnam Briefing. https://www.vietnam-briefing.com/news/why-vietnam-has-become-promising-alternative-for-us-businesses-in-asia.html/

The Investor. (n.d.). American businesses make strong progress in Vietnam. The Investor. https://theinvestor.vn/american-businesses-make-strong-progress-in-vietnam-d6535.html

Vietnam Briefing. (n.d.). Relocating to Vietnam to mitigate the effect of the US-China trade war. Vietnam Briefing. https://www.vietnam-briefing.com/news/relocating-to-vietnam-to-mitigate-the-effect-of-the-us-china-trade-war.html/

VietnamInsiders. (n.d.). American companies are moving factories out of China, as Vietnam is the most mentioned destination. VietnamInsiders. https://vietnaminsiders.com/american-companies-are-moving-factories-out-of-china-as-vietnam-is-the-most-mentioned-destinations/

Reuters. (2017, May 22). U.S. companies sign billions in deals with Vietnam. Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-ge-vietnam/u-s-companies-sign-billions-in-deals-with-vietnam-idUSKBN18R2F2/

LinkedIn. (n.d.). Why so many foreign businesses are moving to Vietnam. LinkedIn. https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/why-so-many-foreign-businesses-moving-vietnam-alberto-vettoretti

Vietnam Briefing. (n.d.). Relocating production: Comparing Vietnam and its peers. Vietnam Briefing. https://www.vietnam-briefing.com/news/relocating-production-comparing-vietnam-and-its-peers.html/

Viettonkin Consulting. (n.d.). Billions pour into Vietnamese businesses: Which U.S. corporation leads the investment race? Viettonkin Consulting. https://www.viettonkinconsulting.com/fdi/billions-pour-into-vietnamese-businesses-which-us-corporation-leads-the-investment-race/

New York Times. (1993, February 8). U.S. businesses turning to Vietnam. New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/1993/02/08/business/us-businesses-turning-to-vietnam.html

U.S. Department of Commerce. (n.d.). Vietnam - import tariffs. U.S. Department of Commerce. https://www.trade.gov/country-commercial-guides/vietnam-import-tariffs

European Commission. (n.d.). EU-Vietnam Free Trade Agreement. European Commission. https://trade.ec.europa.eu/access-to-markets/en/content/eu-vietnam-free-trade-agreement

DHL. (n.d.). The guide to Vietnam import duty and taxes. DHL. https://www.dhl.com/discover/en-my/logistics-advice/import-export-advice/the-guide-to-vietnam-import-duty-and-taxes

World Trade Organization. (n.d.). Tariff profile - Vietnam. WTO. https://www.wto.org/english/res_e/statis_e/daily_update_e/tariff_profiles/vn_e.pdf

FNM Vietnam. (n.d.). Vietnam import tax duties. FNM Vietnam. https://fnm-vietnam.com/import-export/vietnam-import-tax-duties/

Cosmosourcing. (n.d.). How to export from Vietnam to the United States: Regulations and tariffs when importing to the US. Cosmosourcing. https://www.cosmosourcing.com/blog/how-to-export-from-vietnam-to-the-united-states-regulations-and-tariffs-when-importing-to-the-us

Nations Encyclopedia. (n.d.). Vietnam - Customs and duties. Nations Encyclopedia. https://www.nationsencyclopedia.com/Asia-and-Oceania/Vietnam-CUSTOMS-AND-DUTIES.html

US Customs Clearance. (n.d.). Import costs from Vietnam. US Customs Clearance. https://usacustomsclearance.com/process/import-costs-from-vietnam/

Vietnam Briefing. (n.d.). Vietnam's import-export regulations explained. Vietnam Briefing. https://www.vietnam-briefing.com/news/vietnams-import-export-regulations-explained.html/