EP95: Mining the Moon and in Space: Legal Loopholes and Geopolitical Rivalries in Space

Cosmic Conflict: The Future of Space Law and Geopolitical Rivalries

TL;DR:

Space law, governed by treaties like the Outer Space Treaty, sets rules for the peaceful use of space, prohibits claims of sovereignty, and manages responsibilities for space activities. However, with the rise of private companies and new technologies, these laws are outdated, leaving gaps in areas like resource extraction, space debris, and traffic management. Geopolitics in space is heating up, with major powers and big tech competing for dominance through initiatives like the Artemis Accords versus China’s lunar plans. The future of space law will need to address modern challenges, balancing international cooperation, private innovation, and environmental sustainability to prevent space from becoming a battleground for global conflicts.

Introduction

In the vast expanse of space, beyond the traditional boundaries of nation-states, lies a frontier where international law meets the cosmos. Space law, a unique legal construct, governs activities in space, from satellite deployment to lunar exploration. Its impact on geopolitics is profound, shaping international relations, national security, economic ambitions, and the very ethos of global cooperation versus competition.

The Framework of Space Law

Space law originates from the 1967 Treaty on Principles Governing the Activities of States in the Exploration and Use of Outer Space, commonly known as the Outer Space Treaty. This treaty, ratified by over 100 countries, including all space-faring nations, sets foundational principles:

No nation can claim sovereignty over outer space or celestial bodies.

Space is the "province of all mankind," to be freely explored and used for peaceful purposes.

Nations are liable for damage caused by their space objects.

Astronauts are to be treated as "envoys of mankind" and provided aid if in distress.

Additionally, there are other treaties like the Rescue Agreement, the Liability Convention, the Registration Convention, and the Moon Agreement, the Artemis Accords each addressing specific aspects of space activities.

The Rescue Agreement

The Agreement on the Rescue of Astronauts, the Return of Astronauts and the Return of Objects Launched into Outer Space, commonly known as the Rescue Agreement, is an international treaty that complements the Outer Space Treaty by focusing on the rescue and safe return of astronauts and space objects. Here's an explanation of its key aspects:

The primary purpose of the Rescue Agreement is to ensure that if astronauts experience an accident, distress, or make an unintended landing, they are rescued and returned safely to their country of origin or to representatives of the launching authority. Additionally, it addresses the recovery and return of space objects that return to Earth outside of the territory of the launching state.

States that receive information about or discover astronauts in distress or who have landed in their territory must immediately notify the launching authority and the Secretary-General of the United Nations. This notification is crucial for initiating rescue operations.

The state where astronauts land or are found is obligated to take all possible steps to rescue them and provide necessary assistance. This obligation extends to astronauts on the high seas or in any other place not under the jurisdiction of any state, where capable states are encouraged to assist in search and rescue. Once rescued, astronauts must be safely and promptly returned to representatives of the launching authority, ensuring their well-being and security.

If a space object or its component parts returns to Earth outside the launching state's territory, the state where it lands must notify the launching authority and, upon request, recover and return the object. The costs for recovery are generally borne by the launching state, although this aspect can be negotiated.

The agreement applies to both state-led and, implicitly, private space missions, covering what is referred to as the "personnel" of spacecraft, which could include astronauts, cosmonauts, or space tourists.

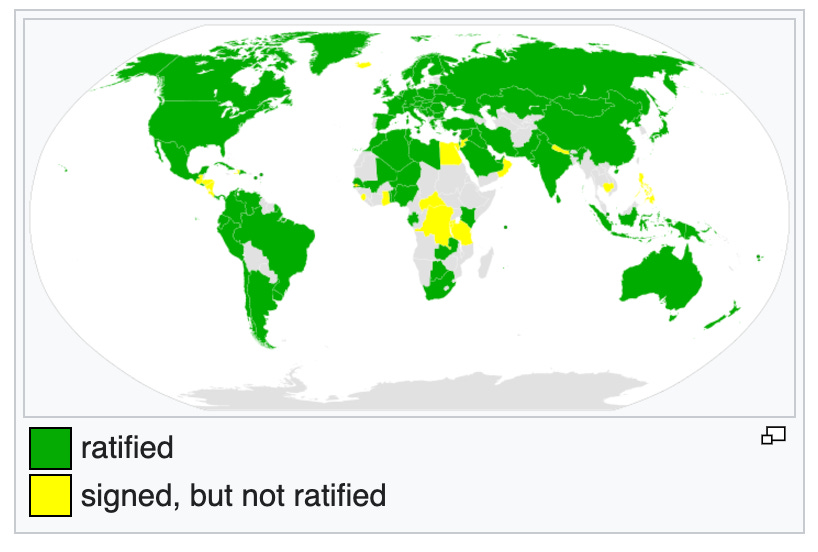

As of January 2022, 98 countries had ratified the treaty, with 23 having signed it. Some international intergovernmental organizations have also declared acceptance of the rights and obligations under this agreement.

This agreement reflects the spirit of international solidarity and the recognition that space activities, while competitive, should not neglect the safety and well-being of individuals involved in these ventures.

Liability Convention

The Convention on International Liability for Damage Caused by Space Objects, often simply referred to as the Liability Convention, is an international treaty that addresses the liability and compensation for damage caused by space objects. It was adopted by the General Assembly of the United Nations in 1971 as a follow-up to the Outer Space Treaty. Here are the key elements of the Liability Convention. The primary purpose of the Liability Convention is to establish a framework for determining responsibility and liability when a space object causes damage, whether on Earth, in air space, or in outer space.

The convention defines "damage" to include loss of life, personal injury or other impairment of health, or loss of or damage to property of States or of persons, natural or juridical, or property of international intergovernmental organizations. The launching State is absolutely liable to pay compensation for damage caused by its space object on the surface of the Earth or to aircraft in flight. This means liability applies regardless of fault. For damage caused elsewhere than on the surface of the Earth to a space object of one launching State or to persons or property on board such a space object by a space object of another launching State, liability is based on fault. If two or more States jointly launch a space object, they are jointly and severally liable for any damage caused by the object.

Claims for compensation must be presented through diplomatic channels. If the parties cannot agree on compensation, the claim can be submitted to a Claims Commission. The Claims Commission, consisting of three members, one appointed by each party and a third selected by agreement between the parties or, if necessary, by the Secretary-General of the United Nations, will decide on the compensation.

A launching State can be exonerated from absolute liability if it proves that the damage resulted either wholly or partially from gross negligence or from an act or omission done with intent to cause damage on the part of the claimant State or its nationals.

It provides a clear legal framework for liability, which is crucial for fostering international cooperation in space activities by ensuring that there is a system for redress in the event of damage. By making states liable for damages, it indirectly encourages better design, operation, and management of space objects to minimize risks. It protects countries that do not have space programs from damages caused by space objects, ensuring they have a mechanism to seek compensation. The convention plays a role in shaping international relations by providing mechanisms for resolving disputes that might arise from space activities.

While the convention holds the launching state liable, there are ongoing discussions about how it applies to private companies launching space objects.

The Liability Convention represents an early and significant attempt to manage the risks associated with space activities in a manner that is equitable and conducive to the peaceful use of outer space.

Ninety-right countries have ratified the Convention on International Liability for Damage Caused by Space Objects (Liability Convention). Nineteen States have signed but not ratified the treaty:

Intergovernmental Organizations that have declared acceptance of rights and obligations under the agreement include: the European Space Agency (ESA), the European Organisation for the Exploitation of Meteorological Satellites (EUMETSAT), the Intersputnik International Organization of Space Communications and the European Telecommunications Satellite Organization (EUTELSAT).

Registration Convention

The Convention on Registration of Objects Launched into Outer Space, commonly known as the Registration Convention, is an international treaty that complements the Outer Space Treaty by establishing a registration system for space objects.

The primary purpose of the Registration Convention is to facilitate the identification of space objects, thereby enhancing transparency, management of space traffic, and aiding in the implementation of the Liability Convention by ensuring there is a clear record of which country is responsible for a given space object.

Each State that launches or procures the launch of a space object shall maintain a national registry of such objects. Details like the name, design, location, and date of launch need to be recorded. States are required to furnish the United Nations with information on each space object they launch. This information includes:

Name of launching State or States

An appropriate designator of the space object or its registration number

Date and territory or location of launch

Basic orbital parameters, including nodal period, inclination, apogee, perigee

General function of the space object

The United Nations maintains a public UN Register of Objects Launched into Outer Space where the information provided by States is entered. This register is managed by the United Nations Office for Outer Space Affairs (UNOOSA). States must also notify the UN of any significant change in the status of the space object (like change in orbit, re-entry, or if the object ceases to be functional). The registration signifies that the State of registry retains jurisdiction and control over the space object and any personnel thereof while in outer space or on a celestial body.

By requiring registration, the convention promotes transparency in space activities, making it easier to hold countries accountable for their space objects. The registry aids in the management of space traffic, reducing potential conflicts and aiding in the tracking of debris. It helps in preventing the misidentification of space objects, which is crucial in times of heightened geopolitical tensions.

Sixty-five states have ratified or acceded to the Registration Convention, and there are also countries that have signed but not ratified it.

Again, as mentioned above, the rise of private sector space activities poses challenges in ensuring all launches are registered, especially when launches are performed by private entities. Not all countries with space capabilities have ratified or acceded to the convention, which can leave gaps in the global registry.

The Registration Convention plays a vital role in the governance of space activities, promoting a safer and more transparent use of outer space.

The Moon Agreement

The Agreement Governing the Activities of States on the Moon and Other Celestial Bodies, commonly known as the Moon Agreement or Moon Treaty, is an international treaty that extends the principles of the Outer Space Treaty to the Moon and other celestial bodies.

The Moon Agreement aims to prevent the militarization of the Moon, ensure the peaceful use of celestial bodies, and establish a framework for the governance of lunar resources. It was adopted by the General Assembly of the United Nations in 1979.

The Agreement declares that the Moon and its natural resources are the common heritage of mankind, prohibiting any State or private entity from claiming sovereignty, ownership, or exclusive rights over any part of the Moon or its resources. According to it, the Moon shall be used exclusively for peaceful purposes, with military bases, installations, and weapons not being placed or used on the Moon. There's an emphasis on scientific investigation of the Moon, promoting international cooperation in such endeavors. States are required to take measures to prevent the disruption of the existing balance of the Moon environment by their activities there.

Although the resources of the Moon are considered the common heritage of mankind, the treaty envisions an international regime to govern the exploitation of these resources when such activities become feasible. This regime is intended to manage the orderly and safe development of natural resources and ensure an equitable sharing of benefits derived from those resources.

Similar to previous space treaties, this agreement stipulates assistance to be given to astronauts, the return of personnel, and notification of activities.

It's the only international treaty that addresses the issue of resource utilization on celestial bodies, although it lacks the specifics needed for practical implementation. The "common heritage of mankind" principle represents a significant philosophical stance on how space resources should be treated, contrasting with more nationalistic or proprietary views.

The Moon Agreement has been ratified by only 18 countries, which notably does not include any major space-faring nations like the United States, Russia, China, or the European Space Agency members. The absence of major space powers has significantly diminished the treaty's impact and enforceability. Countries with significant stakes in space have not ratified it, citing concerns over national interests or the vagueness of how the "common heritage" principle would work in practice.

The Moon Agreement has been somewhat sidelined in practical space policy due to its limited ratification. However, with renewed interest in lunar exploration and resource utilization, especially with plans for lunar bases and mining operations, there's been discussion on revisiting or amending the treaty to make it more relevant to current and future lunar activities.

The Moon Agreement remains a subject of debate in the realm of space law, representing an idealistic approach to space governance that has not yet found widespread acceptance in practice.

Artemis Accords

The Artemis Accords are a set of non-binding bilateral agreements between the United States and other countries or entities interested in participating in the Artemis program, NASA's effort to return humans to the Moon by 2026 and to establish a sustainable presence there, with an eventual goal of human exploration of Mars. The Accords aim to establish a common set of principles to govern the civil exploration and use of outer space, particularly for the Moon, Mars, and beyond, under the Artemis program.

-mBy leading this initiative, the U.S. seeks to shape international space policy in line with its vision for space exploration, potentially creating an alternative framework to initiatives like China's proposed International Lunar Research Station.

As of November 2024, 48 countries have signed the Artemis Accords. These include a mix of established space powers and nations with emerging space programs, spanning Europe, Asia, South America, North America, Africa, and Oceania. Major space powers like Russia and China have not signed, reflecting geopolitical tensions and differing visions for space governance. Russia has criticized the Accords for being too U.S.-centric, while China has its own separate space cooperation frameworks.

Being non-binding, their legal enforceability is limited, relying instead on political commitment.

The Artemis Accords represent a significant step towards defining how space exploration might be conducted in the coming decades, focusing on cooperation, safety, and sustainability in the exploration of the cosmos.

Other agreements, laws, treaties and accords

Beyond the major treaties like the Outer Space Treaty, the Rescue Agreement, the Liability Convention, the Registration Convention, and the Moon Agreement, as well as the more recent Artemis Accords, there are several other notable space laws, treaties, and accords that contribute to the governance of space activities.

1. The Treaty Banning Nuclear Weapon Tests in the Atmosphere, in Outer Space and Under Water (1963). While not exclusively a space law, this treaty, commonly known as the Partial Test Ban Treaty, prohibits nuclear weapons tests in outer space among other environments, contributing to the peaceful use of space.

2. The Declaration of Legal Principles Governing the Activities of States in the Exploration and Use of Outer Space (1963) actually preceded the Outer Space Treaty. It set out basic principles like the freedom of exploration, the non-appropriation of space, and the use of space for peaceful purposes.

3. The Principles Governing the Use by States of Artificial Earth Satellites for International Direct Television Broadcasting (1982) are principles that address the use of satellites for direct television broadcasting, emphasizing sovereignty, non-interference, and the promotion of free flow of information.

4. The Principles Relating to Remote Sensing of the Earth from Outer Space (1986) outlines how remote sensing data should be managed, promoting the use of such data for the benefit of all countries, especially developing nations, and ensuring access to data.

5. The Principles Relevant to the Use of Nuclear Power Sources in Outer Space (1992) provides guidelines for the safe use of nuclear power in space, focusing on safety, notification, and emergency response.

6. The Declaration on International Cooperation in the Exploration and Use of Outer Space for the Benefit and in the Interest of All States (1996) encourages cooperation in space activities, particularly considering the needs of developing countries, promoting the sharing of benefits from space activities.

Other Regional Agreements of Note

The Convention for the Establishment of a European Space Agency (ESA) (1980). While not a global treaty, the ESA Convention establishes a framework for cooperation among European countries in space science, technology, and applications.

Other items of note:

The Space Launch Competitiveness Act (U.S., 2015). While not an international treaty but it is significant as it grants U.S. citizens the right to engage in commercial exploration and exploitation of space resources, aligning with international law but adding a national legislative layer.

The International Telecommunication Union (ITU) Constitution and Convention (1992, with origins in 1865). While primarily about telecommunications, the ITU's role includes the allocation of radio frequencies and satellite orbits, crucial for space communications.

The Convention on the International Mobile Satellite Organization (Inmarsat) (1976, amended in 1998) focuses on the provision of maritime, aeronautical, and land-mobile satellite communication services.

Emerging and Proposed Agreements:

The Draft Treaty on the Prevention of the Placement of Weapons in Outer Space, the Threat or Use of Force against Outer Space Objects (PPWT) (2008). This was proposed by Russia and China. This draft treaty seeks to prevent an arms race in outer space by prohibiting weapons placement in space, although it hasn't been widely adopted.

The Hague International Space Resources Governance Working Group (2016). While not a treaty, this working group is developing principles for the governance of space resource activities, reflecting the growing interest in space mining.

These laws, treaties, and accords collectively aim to ensure that space remains a domain for peaceful exploration and use, balancing national interests with the common good of humanity. However, the rapid pace of space technology development, private sector involvement, and geopolitical shifts continue to challenge and evolve this legal framework.

Complications involving commercial space companies

The advent and expansion of private commercial companies in space have indeed highlighted several limitations and inadequacies in the existing framework of space laws, treaties, and accords. The treaties above primarily bind countries, not private entities directly. While states are responsible for authorizing and supervising the activities of non-governmental entities under the Outer Space Treaty, this indirect responsibility can lead to jurisdictional grey areas. Private companies might operate under national laws that are more permissive than international treaties, leading to discrepancies in how space law is applied.

The Registration Convention requires states to register space objects, but with private launches, ensuring all launches are registered and the liability framework is applied uniformly can be challenging, especially if companies launch from international waters or less regulated countries.

While the Artemis Accords and other principles promote debris mitigation, the rapid increase in satellite launches by private companies exacerbates the debris problem. There's no enforceable international law specifically addressing how private companies should manage space debris or the environmental impact of their operations.

The current treaties do not provide a detailed framework for Space Traffic Management (STM) managing traffic in space, especially in Low Earth Orbit (LEO) where private constellations are becoming dense. This leads to potential safety issues, like close calls or collisions.

The issue of intellectual property rights in space, especially concerning inventions or discoveries made in space, isn't covered effectively by current space law.

The legal frameworks do not fully address the commercialization of space, like space tourism, mining, or manufacturing, leading to potential exploitation without clear guidelines on rights, safety, or environmental impact.

There's little in the treaties to prevent monopolistic practices or ensure fair competition in space, which could become problematic as private companies dominate certain aspects of space commerce.

International space law lacks strong enforcement mechanisms, particularly when private entities are involved. Disputes involving private companies might not be easily resolved through the current state-to-state mechanisms.

The treaties do not specify how to handle disputes involving private companies, leaving room for complex legal battles that might not align with international agreements.

The rapid evolution of space activities driven by private sector innovation has outpaced the legal frameworks designed in an era dominated by state actors, underscoring the urgent need for legal evolution in space governance.

Resource exploitation and mining is a very big issue that needs to be resolved. The governance of rights over minerals and resources recovered from space is primarily influenced by a mix of international treaties, national laws, and more recent accords and principles. There is a great deal of ambiguity especially as it applies to private, non-governmental efforts.

The in Article II of the Treaty on Principles Governing the Activities of States in the Exploration and Use of Outer Space, including the Moon and Other Celestial Bodies (Outer Space Treaty, 1967), it explicitly states that outer space, including the Moon and other celestial bodies, is not subject to national appropriation by claim of sovereignty, by means of use or occupation, or by any other means. This has been interpreted to mean that no one can claim ownership over celestial bodies themselves. However, is mineral resource extraction a claim of ownership over a celestial body?

There is ambiguity regarding whether this prohibition extends to resources extracted from celestial bodies. The treaty does not explicitly address the ownership rights over resources once they have been removed from their natural state.

Article 11 of the Agreement Governing the Activities of States on the Moon and Other Celestial Bodies (Moon Agreement, 1979) declares the Moon and its natural resources to be the common heritage of mankind, meaning no state or private entity can claim ownership over them. However, it also mentions the future establishment of an international regime to govern the exploitation of these resources when such becomes feasible. The Moon Agreement has been ratified by only 18 countries, none of which are major space-faring nations, limiting its practical impact.

We find some greater clarity in the Artemis Accords that affirm that the extraction of space resources does not inherently constitute national appropriation under Article II of the Outer Space Treaty. This interpretation supports the idea that private entities or states can utilize resources extracted from space. To manage potential conflicts, the Accords propose the establishment of "safety zones" around operation sites to avoid harmful interference during resource extraction activities.

Several countries have passed domestic legislation to address the issue of space resource rights, reflecting a more proactive approach. The United States has the Commercial Space Launch Competitiveness Act (2015). This act grants U.S. citizens the right to engage in commercial exploration for and commercial recovery of space resources free from harmful interference. It specifies that any resources obtained are entitled to the U.S. citizen or entity involved, provided it's in accordance with applicable law, including international obligations.

Luxembourg has the Law on the Exploration and Use of Space Resources (2017). Similar to the U.S., Luxembourg's law recognizes the right of private operators to own resources they extract from space, stating that space resources are capable of being appropriated.

The United Arab Emirates has Federal Law No. 12 of 2019 on the Regulation of the Space Sector. This law also permits the ownership of space resources by UAE nationals or companies.

Japan has the Law on Promoting the Use of Space Resources (2021). It has enacted laws to encourage space resource activities, allowing for the ownership of extracted resources.

The debate between national interests in resource exploitation and the principle of the common heritage of mankind remains unresolved, complicating the legal landscape for resource rights in space.

There's also the question of how resource extraction should be conducted to preserve the space environment, an aspect not fully addressed by current laws.

The combination of international treaties, national legislation, and bilateral accords like the Artemis Accords reflects an evolving but still largely incomplete framework for managing rights over space resources. The tension between encouraging private sector innovation and adhering to the principles of international space law continues to shape this area of space governance.

However, while these treaties form the backbone of international space law, their vagueness and the emergence of new space actors have led to evolving interpretations and applications.

Geopolitical Implications

The Outer Space Treaty prohibition on nuclear weapons in space does not prevent other forms of military use, like intelligence gathering or potential space-based weaponry platforms. This has led to a militarization of space, where countries like the United States, Russia, and China develop capabilities for space warfare, impacting global military strategies.

As commercial space ventures grow, particularly in satellite technology, space tourism, and asteroid mining, the economic stakes in space increase. The ambiguity in resource rights under current laws fosters a competitive environment where countries like the U.S. with the Commercial Space Launch Competitiveness Act (2015) assert rights over resources their citizens extract, prompting geopolitical friction and a race for space resources.

Space has been a domain for showcasing technological prowess and fostering international collaboration, as seen with the International Space Station (ISS). However, with rising nationalism and strategic competition, particularly between the U.S. and China, space is increasingly viewed as a theater for geopolitical rivalry. Initiatives like the Artemis Accords by the U.S., aiming to set norms for lunar exploration, contrast with China and Russia's plans for their lunar station, indicating potential new 'blocs' in space.

The rapid advancement of private sector involvement in space, spearheaded by companies like SpaceX and Blue Origin, challenges the existing legal framework. The debate over who regulates these activities, how international laws apply to private entities, and how to manage debris and environmental impact in space, all have geopolitical ramifications.

The regulatory landscape becomes complex when private entities begin to eclipse state-run programs in innovation and access to space. This scenario raises questions about jurisdiction, liability, and the applicability of space treaties to non-state actors. For instance, if a private company causes damage in space or on another celestial body, under whose jurisdiction would they fall? This leads to discussions on whether new treaties or amendments to existing ones are necessary to clarify these ambiguities.

Achievements in space continue to be a source of national pride and a tool for soft power. The ability to perform high-profile space missions, like Mars rovers or lunar landings, not only boosts a nation's scientific reputation but also its global image. This competition can influence international alliances, trade agreements, and even public opinion on a global scale.

Space technology often has dual-use applications, impacting terrestrial technologies. The development of satellite technology has led to advancements in communication, navigation (GPS), and surveillance, which have military, economic, and social implications. Countries invest in space not only for the prestige but for the technological benefits that can bolster their economies and security apparatus.

Future Directions and Considerations

There's a growing recognition that the current treaties, primarily products of the Cold War era, might need updates or supplementary agreements to address modern challenges like space traffic management, debris mitigation, and resource extraction rights. The lack of a global consensus on these matters could lead to unilateral actions by nations or companies, potentially escalating tensions.

Countries like India, Japan, and the United Arab Emirates are entering the space arena, not just as participants but as potential influencers of space law. Their involvement could lead to a diversification of space governance, with new perspectives on how space should be used and regulated.

The dual nature of space as both a cooperative and competitive domain will continue to shape geopolitics. While space has been a platform for international cooperation, the potential for conflict over resources, strategic high ground, or even accidents due to space debris could lead to new forms of geopolitical tension or necessitate novel diplomatic efforts.

The role of private corporations in shaping space law cannot be understated. Their interests, capabilities, and sometimes their agendas might push for different interpretations or applications of space law, influencing national policies and, by extension, international relations.

Conclusion:

Space law, while designed to ensure the peaceful exploration of space, has become a pivotal element in the geopolitical chessboard. As nations and private entities push the boundaries of space exploration, the law must evolve to maintain peace, encourage cooperation, and prevent the cosmos from becoming another arena for terrestrial conflicts. The future of space law will likely involve balancing sovereignty, commercial interests, environmental concerns, and the shared heritage of humanity, all while navigating the complex web of international politics. The way these laws are interpreted and enforced will continue to shape not only our journey to the stars but also the geopolitical landscape on Earth.

Sources:

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0265964606000245

https://academic.oup.com/ia/article-abstract/73/4/776/2624393?redirectedFrom=fulltext

https://www.wilsoncenter.org/article/global-legal-landscape-space-who-writes-rules-final-frontier

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0265964623000279

https://www.spacefoundation.org/space_brief/international-space-law/

https://www.geostrategy.org.uk/britains-world/how-will-space-impact-the-future-of-geopolitics/

https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-981-97-0714-0_2