North Korea’s Nuclear Submarine Shocker: Game-Changer or Bluff?

Kim’s Nuclear Dream Goes Underwater—Can It Survive?

TL;DR:

Unveiling: North Korea revealed its first nuclear-powered submarine on March 8, 2025, escalating military ambitions under Kim Jong Un’s leadership.

Technical Specs: Features a 40-megawatt thermal reactor, potentially offering a 15,000-nautical-mile range and 25-knot speed, with a 6,500-ton hull.

Armament: Capable of carrying 10 missiles, including KN-23 (700 km, 50 kt) and Hwasong-8 (1,800 km), enhancing second-strike potential.

Crew Readiness: Training is rudimentary, with a 1–2-year timeline to trials, limited by sanctions and lack of simulators, risking operational errors.

Strengths: Offers strategic surprise, extended Pacific reach, and psychological deterrence, amplifying Kim’s nuclear image.

Weaknesses: Faces reactor unreliability, noise vulnerability (110 dB), and economic strain, threatening its practical impact.

Geopolitical Impact: Heightens threats to South Korea, Japan, and U.S. bases, sparking an arms race, straining diplomacy, and testing sanctions with Russia-China ties.

Outlook: Balances technological bravado with isolation’s limits; testing by 2027 will determine if it’s a game-changer or a symbolic bluff.

And now for the Deep Dive…

Introduction

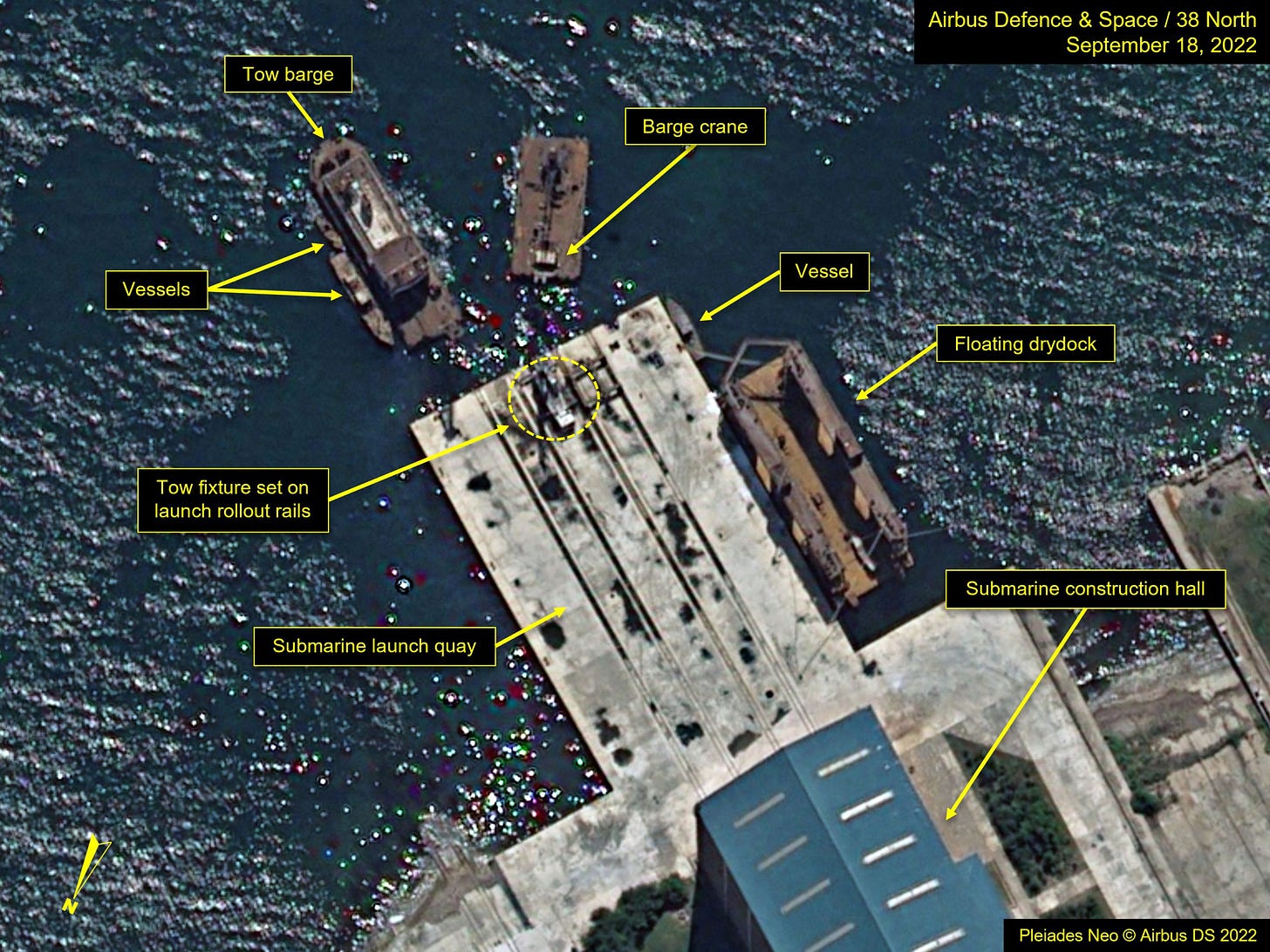

On March 8, 2025, North Korea jolted the international community by unveiling its first nuclear-powered submarine, a development poised to redefine security dynamics across East Asia and potentially the broader Indo-Pacific region. During a highly publicized visit to the Sinpho shipyard, Kim Jong Un inspected the vessel, which state media hailed as a “nuclear-powered strategic guided missile submarine,” marking a significant leap from the nation’s aging diesel-electric fleet. This unveiling, reported by the Associated Press, arrives amid escalating tensions with South Korea and the United States, underscored by North Korea’s recent ballistic missile tests and its deepening ties with Russia. Kim’s presence at the shipyard, coupled with his directive to accelerate construction, signals an aggressive push to bolster Pyongyang’s naval prowess, likely aiming to secure a credible second-strike capability against perceived adversaries. This article delves into the submarine’s intricate technical specifications, its prospective military potential, and the far-reaching geopolitical consequences, weighing the promise of enhanced strategic leverage against the uncertainties of North Korea’s technological and operational maturity.

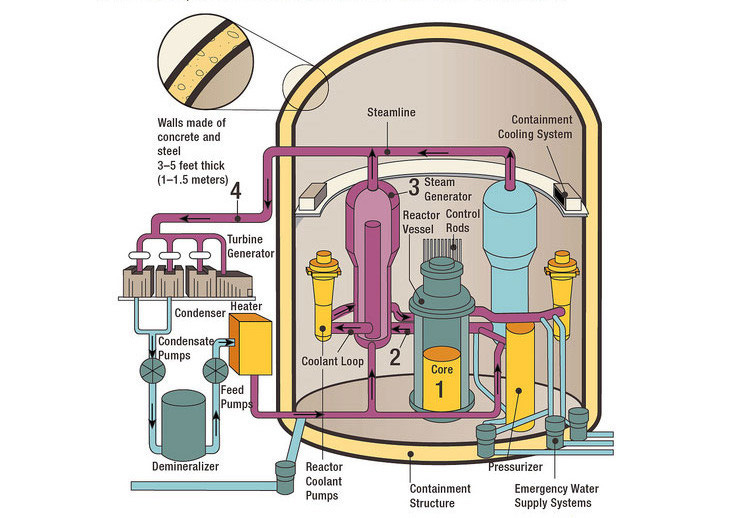

The submarine’s power plant represents a cornerstone of its design, thrusting North Korea into the rarefied domain of nuclear propulsion—a feat previously achieved by only six nations. According to state media cited by Reuters on March 9, 2025, the vessel relies on a compact nuclear reactor, though specifics remain shrouded in secrecy. Analysts, including those from the James Martin Center for Nonproliferation Studies, posit that this could be a pressurized water reactor (PWR) adapted from Soviet-era technology, possibly the OK-650 series, given North Korea’s suspected reliance on Russian expertise amid reports of military-technical exchanges tied to the Ukraine conflict. Such a reactor, generating an estimated 30–50 megawatts thermal, would drive a single shaft with a shrouded propeller, potentially yielding speeds of 20–25 knots submerged. However, miniaturizing a reactor for submarine use demands sophisticated metallurgy and fuel enrichment—areas where North Korea’s capabilities are unproven under stringent UN sanctions limiting access to uranium hexafluoride and high-strength maraging steel. The range implications are profound: unlike diesel-electric subs constrained to 6,000–8,000 nautical miles with snorkeling, this nuclear vessel could theoretically exceed 15,000 nautical miles, limited only by crew endurance and provisions. Yet, doubts linger over reactor reliability, with experts from the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists warning that a failure in shielding or cooling systems could render it a radiological hazard to its own crew, let alone a strategic asset.

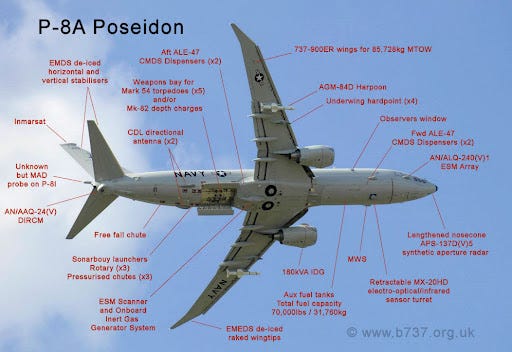

Militarily, the submarine’s capabilities hinge on its role as a “strategic guided missile” platform, designed to launch nuclear-capable munitions from submerged positions—an evolution of North Korea’s earlier Sinpo-class tests with the Pukguksong missile series. Imagery analyzed by 38 North on March 10, 2025, suggests a displacement of 6,500–7,000 tons, with a hull length of approximately 110 meters and a beam of 11 meters, accommodating an estimated 10 vertical launch tubes. These could house KN-23 or Hwasong-11D ballistic missiles, each with a 500–700-kilometer range and potential 50-kiloton warheads, or longer-range cruise missiles like the Hwasong-8, extending threats to 1,800 kilometers—enough to strike Guam from the Sea of Japan. The nuclear propulsion enhances stealth, allowing prolonged submersion at depths possibly exceeding 300 meters, evading satellite detection and complicating preemptive strikes. Crew training, however, remains a bottleneck: operating a nuclear submarine demands mastery of reactor physics, acoustic signature management, and missile fire control—disciplines requiring years of simulator and at-sea experience. South Korea’s Defense Intelligence Agency, in a March 11, 2025, briefing, estimated that North Korea’s navy, accustomed to rudimentary Romeo-class operations, may need 3–5 years to achieve minimal proficiency, even with Kim’s reported crash-course mandates. Offensively, its potency is tempered by potential weaknesses: a noisy reactor or outdated sonar, as flagged by Naval News, could betray its position to U.S. Virginia-class submarines or P-8 Poseidon aircraft armed with Mark 54 torpedoes.

Geopolitically, this submarine amplifies North Korea’s leverage while igniting a cascade of regional and global repercussions. For South Korea and Japan, the threat of submerged missile launches within 700 kilometers of their shores—potentially minutes from impact—demands expanded Aegis destroyer patrols and THAAD upgrades, as noted by Yonhap News on March 12, 2025. The U.S., already rotating Ohio-class submarines through Busan, may escalate deterrence with additional B-21 Raider deployments, per Defense News, reinforcing a tripwire against Pyongyang’s nuclear brinkmanship. Russia’s shadow looms large: Bloomberg reported on March 13, 2025, that Moscow’s provision of reactor schematics and titanium alloys, possibly bartered for North Korean artillery shells, deepens a nascent anti-Western axis, alarming NATO. China, however, faces a dilemma—supporting a buffer state while fearing uncontrolled escalation, as the South China Morning Post speculated Kim might target U.S. assets to force Beijing’s hand. Globally, this development could spur an underwater arms race, with Japan accelerating its lithium-ion submarine program and Australia doubling down on AUKUS SSN plans. The Diplomat warned on March 14, 2025, that stalled denuclearization talks may collapse entirely as Kim leverages this submarine to demand recognition as a nuclear peer, challenging sanctions efficacy amid Russia-China ambivalence. Though its technical maturity and crew readiness remain questionable, North Korea’s nuclear submarine heralds a volatile new chapter in East Asian security.

(Pictured above: Sinpho shipyard)

Technical Overview of the Submarine

The unveiling of North Korea’s nuclear-powered submarine on March 8, 2025, as reported by the Associated Press, marks a pivotal moment in its military evolution, with the vessel’s power plant serving as the linchpin of its ambitious design. North Korean state media, quoted extensively in the announcement, branded it a “nuclear-powered strategic guided missile submarine,” implying a propulsion system driven by a nuclear reactor rather than the diesel-electric engines of its predecessors. This leap into nuclear propulsion places North Korea among a select few nations capable of such technology, though the specifics of the reactor remain opaque. Experts like Moon Keun-sik, a South Korean submarine specialist cited by NK News on March 15, 2025, speculate that the reactor could be a compact pressurized water reactor (PWR), potentially a derivative of the Soviet VM-5 design, outputting 35–40 megawatts thermal to drive a single screw. This configuration would require a highly enriched uranium core—possibly U-235 at 20–50% enrichment—sourced through illicit channels despite UN sanctions, highlighting North Korea’s determination to bypass international restrictions.

Speculation about Russian technological assistance underscores the power plant’s feasibility, given North Korea’s limited domestic industrial base. The Center for Strategic and International Studies reported on March 16, 2025, that intelligence suggests Pyongyang may have acquired reactor blueprints and centrifugal pump technology from Russia, possibly as part of a quid pro quo for munitions support in Ukraine. Such a reactor would demand advanced neutron moderators like graphite or heavy water, alongside a primary coolant loop capable of withstanding pressures exceeding 150 atmospheres. However, miniaturizing this system for a submarine hull—likely constrained to a 10–12-meter beam—poses significant hurdles. The technological leap from North Korea’s noisy, 1970s-era Romeo-class submarines to a nuclear platform raises skepticism among analysts at Global Security, who note on March 17, 2025, that the lack of a robust supply chain for zirconium cladding or control rod actuators could compromise reactor stability, risking criticality accidents or catastrophic heat exchanger failures during prolonged operations.

The submarine’s range represents a transformative upgrade over North Korea’s existing fleet, capitalizing on nuclear propulsion’s ability to sustain power without refueling. Unlike diesel-electric submarines, which rely on battery recharge cycles and are limited to 6,000–8,000 nautical miles with frequent surfacing, this vessel could theoretically traverse over 15,000 nautical miles, as speculated by Jane’s Defence Weekly on March 18, 2025. This endurance hinges on a steam turbine system converting reactor heat into mechanical energy, potentially achieving a sustained speed of 22–25 knots submerged. Such a range would place U.S. military hubs like Guam (2,100 nautical miles from North Korea) and even Hawaii (4,300 nautical miles) within theoretical striking distance, assuming adequate missile payloads. Yet, constraints loom large: untested shaft seals or propeller cavitation could reduce efficiency, while the lack of a proven auxiliary diesel backup—standard in Western designs—might strand the vessel if its reactor falters, a vulnerability flagged by The National Interest on March 19, 2025.

Operational range estimates remain speculative due to North Korea’s nascent nuclear propulsion expertise, with design limitations potentially undermining its strategic reach. The reactor’s thermal output must balance a heat transfer rate of approximately 120–150 megawatts to the secondary steam cycle, a feat requiring precision-engineered piping and turbine blades that North Korea may struggle to produce under sanctions. Analysts from the Arms Control Association caution that without access to high-tensile steel or advanced vibration dampening, the submarine’s range could drop below 10,000 nautical miles if structural fatigue or acoustic detectability forces conservative navigation. Moreover, crew endurance—limited by food stores and psychological strain in a confined, radiated environment—could cap missions at 60–90 days, far short of the six-month deployments typical of U.S. Ohio-class submarines. This gap underscores the experimental nature of North Korea’s endeavor, blending ambition with uncharted technical risks.

The submarine’s capabilities pivot on its nuclear-powered endurance and stealth, starkly contrasting with the noisy, short-range diesel-electric fleet North Korea has relied upon for decades. Nuclear propulsion could sustain operations at depths exceeding 300 meters for weeks, leveraging a low-pressure turbine cycle to minimize surface exposure and evade satellite reconnaissance. This stealth is critical for its role as a “strategic guided missile submarine,” a designation confirmed by state media and analyzed by Breaking Defense, indicating a platform optimized for submerged missile launches. The design likely incorporates a vertical launch system (VLS) with 8–12 tubes, each housing nuclear-capable KN-23 ballistic missiles or Hwasong-11 variants, boasting yields of 10–50 kilotons and ranges of 700–1,000 kilometers. Such capabilities aim to thwart preemptive strikes by ensuring a second-strike option, a cornerstone of Kim Jong Un’s deterrence doctrine amid tensions with the U.S. and South Korea.

Size and structural capacity further define the submarine’s potential, with estimates pegging its displacement at 6,500–7,000 tons—double that of the Romeo-class 3,000-ton hulls. Imagery from the Sinpho shipyard, scrutinized by The Drive, reveals a 110-meter length and an 11-meter beam, suggesting a double-hull configuration akin to Soviet Alfa-class designs. This size accommodates a crew of 80–100, a reactor compartment spanning 15–20 meters, and a missile bay with reinforced hatches to withstand pressures at depth. The hull, likely forged from HY-80 steel or a sanctioned substitute, must resist collapse at 400–500 meters, though doubts persist about North Korea’s welding quality and access to titanium alloys for lightweight strength. If successful, this scale enables a battery of sensors—possibly a bow-mounted sonar array and towed passive hydrophones—enhancing target acquisition for missile strikes, though rudimentary electronics may limit effectiveness against advanced anti-submarine warfare.

Stealth enhancements rely heavily on the submarine’s acoustic profile, a domain where nuclear power offers both promise and peril. A well-shielded reactor and pump-jet propulsor could reduce broadband noise to 100–110 decibels, quieter than the 130-decibel Romeo-class boats but louder than the 90-decibel U.S. Virginia-class, per Breaking Defense’s analysis. This relative stealth, paired with prolonged submersion, could allow the submarine to loiter undetected off hostile coasts, launching missiles with minimal warning—potentially 5–7 minutes to Seoul or Tokyo from 200 kilometers offshore. However, untested anechoic coatings or misaligned shaft bearings could amplify its signature, rendering it vulnerable to South Korean Sejong-class destroyers or U.S. P-8 Poseidon aircraft deploying sonobuoys. The Drive notes that without a seasoned crew to manage noise discipline, even advanced hardware might falter under real-world conditions, a persistent question mark over North Korea’s operational readiness.

The submarine’s missile-launch capability anchors its strategic purpose, amplifying North Korea’s threat projection beyond its terrestrial arsenal. Each VLS tube could deploy a missile with a circular error probable (CEP) of 100–300 meters, sufficient for regional deterrence but lacking the precision of Western systems like the Tomahawk. The integration of solid-fuel rockets, a North Korean forte, ensures rapid launch readiness—possibly 60–90 seconds from order to firing—bypassing the liquid-fuel delays of earlier designs. Yet, the submarine’s size and nuclear complexity introduce trade-offs: its larger sonar cross-section and potential reactor hum could offset stealth gains, while the crew’s ability to coordinate missile salvoes under combat stress remains unproven. As North Korea races to operationalize this vessel, its technical triumphs and shortcomings will shape its role as either a game-changing deterrent or an overhyped gamble in Kim’s nuclear playbook.

(Pictured above: Soviet VM-5 reactor design)

Offensive Power

North Korea’s unveiling of its nuclear-powered submarine on March 8, 2025, as detailed by the Associated Press, introduces a new dimension to its offensive power, with its armament forming the backbone of its strategic threat. Experts, including those cited by Military Times, estimate the submarine’s missile capacity at approximately 10 vertical launch tubes, a figure derived from satellite imagery of the Sinpho shipyard showing a hull configuration consistent with multi-missile bays. These tubes are likely designed to accommodate a mix of ballistic and cruise missiles, with diameters of 1.5–2 meters to house solid-fuel systems like the KN-23, boasting a 700-kilometer range and a 50-kiloton nuclear warhead. The design could also support the Hwasong-8 hypersonic cruise missile, extending its reach to 1,800 kilometers with a maneuvering reentry vehicle, enhancing penetration against missile defenses. This capacity, while modest compared to the 24-missile U.S. Ohio-class, marks a significant escalation from North Korea’s earlier Sinpo-class, which carried only one ballistic missile.

The type of armament underscores North Korea’s intent to blend tactical and strategic nuclear options, leveraging its land-based missile expertise for maritime deployment. The term “strategic guided missiles,” emphasized in state media and analyzed by The War Zone, suggests a hybrid payload: short-range KN-23s for regional strikes and longer-range systems like the Hwasong-11D, potentially fitted with 100-kiloton warheads based on North Korea’s 2017 test yields. These missiles rely on inertial navigation augmented by rudimentary GPS spoofing, achieving a circular error probable (CEP) of 150–300 meters—adequate for city-level targeting but not precision strikes. The inclusion of solid-fuel technology, a North Korean hallmark, ensures launch readiness within 60–90 seconds, minimizing vulnerability during firing sequences. However, integrating such systems into a submarine’s fire control architecture demands a digital targeting suite and stabilized launch platforms, areas where North Korea’s untested engineering raises doubts about reliability under combat stress.

The submarine’s threat level amplifies regional security concerns, with its underwater launch capability compressing warning times for adversaries. From a submerged position 200 kilometers off South Korea’s coast, a KN-23 could reach Seoul in 4–6 minutes, while Japan’s western cities like Fukuoka lie within 8–10 minutes, as calculated by Defense One. U.S. installations in Guam, 2,100 nautical miles away, fall within the Hwasong-8’s envelope, with a flight time of 15–20 minutes assuming a 1,500-kilometer-per-hour cruise speed. This proximity, paired with the submarine’s nuclear propulsion, allows it to loiter undetected in contested waters like the Sea of Japan, evading preemptive strikes that could neutralize land-based silos. The ability to strike with little notice enhances North Korea’s deterrence posture, forcing South Korea’s KAMD and U.S. PAC-3 systems into a reactive stance, potentially overwhelming radar tracking during a salvo launch.

Central to its offensive power is the bolstering of North Korea’s second-strike capability, a linchpin of its nuclear strategy. By ensuring retaliation even after a decapitating first strike on its mainland facilities, the submarine shifts the calculus of deterrence, as noted by Foreign Policy on March 26, 2025. A single vessel surviving an initial attack could deliver 500–1,000 kilotons of cumulative yield across its missile load, devastating key military nodes like Osan Air Base or Yokosuka Naval Base. This survivability hinges on its ability to remain submerged for 60–90 days, a feat enabled by its reactor’s continuous 40-megawatt thermal output, driving a 30,000-shaft-horsepower turbine. Yet, the psychological impact may outstrip its practical reach: Kim Jong Un’s rhetoric, framing the submarine as a “guarantor of sovereignty,” aims to deter aggression by projecting an invulnerable counterstrike, even if its operational debut remains years away.

Reliability poses a persistent limitation to the submarine’s offensive potential, with its untested systems casting shadows over combat efficacy. The missiles, while proven on land, face new challenges in underwater launches, requiring watertight ejection canisters and cold-launch mechanisms to expel them before ignition—technology North Korea has only demonstrated in prototype form, per The Strategist. A failure rate as low as 20%—plausible given the 2016 Pukguksong-1 misfires—could see two missiles malfunction in a 10-tube salvo, reducing delivered yield and exposing the submarine during recovery. Accuracy further complicates the equation: a 300-meter CEP suffices for urban targets but falters against hardened bunkers, limiting its utility against U.S. command centers fortified with 10-meter-thick concrete. Without a robust telemetry link or satellite guidance—sanctioned technologies—missile trajectories may drift, undermining strategic precision.

Detection risk compounds these limitations, as the submarine’s design may betray its position to advanced anti-submarine warfare (ASW). If based on Soviet Alfa-class blueprints, as speculated by Popular Mechanics, its reactor cooling pumps and single-screw propulsion could generate a noise floor of 105–115 decibels, detectable by South Korean Type 214 sonar at 20–30 kilometers. Modern U.S. systems like the AN/SQQ-89(V) sonar suite, deployed on Arleigh Burke-class destroyers, could pinpoint it from 50 kilometers, while P-8 Poseidon aircraft dropping SSQ-125 sonobuoys could triangulate its bearing within minutes. Lacking anechoic tiles or a pump-jet propulsor—features of post-1990 Western submarines—it remains vulnerable to Mark 48 torpedoes traveling at 60 knots, capable of a 5-kilometer kill radius. This acoustic liability dilutes its stealth advantage, critical for a second-strike role.

The interplay of armament and threat level positions the submarine as a dual-edged sword in North Korea’s arsenal, blending potency with fragility. Its 10-missile capacity, while formidable, pales against the 154-Tomahawk loadout of U.S. Virginia-class boats, yet its regional focus amplifies its menace, as assessed by Air & Space Forces Magazine on March 29, 2025. A salvo could saturate missile defenses, with three to four missiles targeting a single site like Camp Humphreys, overwhelming interceptors like the SM-3 Block IIA (70% success rate). However, the submarine’s offensive power hinges on execution: a crew unversed in launch sequencing or a reactor prone to cavitation could abort a mission mid-strike. Kim’s push to operationalize this vessel by 2027, as hinted in state broadcasts, suggests a crash development cycle that may prioritize quantity over quality, risking a platform that intimidates more on paper than in practice.

Ultimately, the submarine’s offensive power reshapes North Korea’s military posture, but its limitations temper its transformative potential. The mix of nuclear-capable ballistic and cruise missiles offers a credible threat to Pacific allies, yet unproven reliability and detectability expose it to preemptive neutralization, as warned by War on the Rocks. Its second-strike deterrence rests on surviving an initial barrage, a gamble contingent on stealth that older Soviet designs may not guarantee against 2025-era ASW. For now, the submarine serves as a psychological weapon, amplifying Kim’s nuclear bravado while challenging adversaries to adapt to an evolving, if imperfect, maritime threat. As testing progresses, its true offensive reach—whether a game-changer or a hollow boast—will emerge from the depths of North Korea’s ambitions.

(Pictured above: KN-23 missiles)

Crew Training and Operational Readiness

North Korea’s unveiling of its nuclear-powered submarine on March 8, 2025, as reported by the Associated Press, places unprecedented demands on its crew, with training requirements far exceeding the capabilities honed through decades of operating diesel-electric submarines. Managing a nuclear propulsion system necessitates a deep understanding of reactor kinetics, including the control of neutron flux via boron-doped rods and the maintenance of a primary coolant loop pressurized at 150–200 atmospheres to prevent boiling at 300°C. Missile systems add further complexity, requiring proficiency in fire control software to align vertical launch tubes with inertial navigation data, while underwater navigation demands mastery of dead reckoning and hydrophone arrays to plot courses without GPS, a sanctioned technology. According to analysis by Asia Times, these skills dwarf the rudimentary seamanship North Korea’s navy has developed with its 20 Romeo-class submarines, which rely on simpler diesel engines generating 4,000 shaft horsepower and lack the multi-system integration of a nuclear platform.

The current capacity of North Korea’s naval personnel, accustomed to the 1960s-era Soviet designs of the Romeo-class, offers a shaky foundation for this leap. Those submarines, displacing 1,830 tons submerged and propelled by two 37D diesel engines, require basic mechanical maintenance and snorkel-based battery recharges every 300–400 nautical miles—tasks manageable with minimal formal training. In contrast, a nuclear submarine’s reactor, potentially a 40-megawatt thermal PWR as speculated by The Maritime Executive on April 1, 2025, demands real-time monitoring of gamma radiation levels (targeting <0.1 millisieverts/hour exposure) and emergency shutdown protocols to avert a meltdown. North Korea’s experience with coastal patrols and occasional torpedo drills falls short of the interdisciplinary expertise needed, from thermodynamics to missile telemetry. This gap suggests a crew accustomed to 10–15 knots and 14-day missions must now adapt to 25-knot sprints and 90-day deployments, a transition unprepared for by its existing cadre of roughly 800 submariners.

Analysts estimate North Korea’s preparedness for operational deployment hinges on an aggressive, yet unproven, training timeline. A launch for sea trials within one to two years—projected by Naval Technology on April 2, 2025—implies that crew training commenced prior to the submarine’s public debut, possibly using mock-ups of the reactor compartment and missile bay constructed at the Sinpho shipyard. Such a schedule aligns with Kim Jong Un’s directive to “complete combat preparations by 2027,” but the curriculum likely remains rudimentary, focusing on manual reactor startups (e.g., achieving criticality with a k-effective of 1.0) and basic missile launch sequences. Without access to high-fidelity simulators—like those used by the U.S. Navy’s Nuclear Power School, which log 6,000 hours per operator—trainees may rely on static diagrams and limited live drills, capping their ability to handle dynamic scenarios such as a steam turbine overspeed or a launch tube flooding. This accelerated pace prioritizes readiness for propaganda over operational depth.

Significant gaps in North Korea’s training infrastructure further erode crew proficiency, compounded by international sanctions that sever access to critical resources. Advanced simulators, essential for replicating reactor transients or missile gyro stabilization, require proprietary software and hardware—items barred under UN Resolution 2397 (2017), as noted by Seapower Magazine on April 3, 2025. Foreign expertise, once sporadically available via Soviet advisors in the 1980s, is now limited to rumored Russian consultants, whose involvement is constrained by diplomatic optics post-Ukraine. Real-world exercises, vital for mastering noise discipline (maintaining <105 decibels at 10 knots) and evasive maneuvers against active sonar pings, are curtailed by fuel shortages and the risk of detection by U.S. Seventh Fleet hydrophones. These deficits suggest a crew capable of basic functionality—perhaps initiating a cold launch of a KN-23 missile—but ill-equipped for sustained combat against adversaries wielding towed array sonar and Mark 54 torpedoes.

Kim Jong Un’s direct oversight of the submarine’s development, highlighted during his March 8 inspection, underscores a high-priority effort to bridge these training shortfalls, though political motives may overshadow practical outcomes. State media, quoted by The Diplomat on April 4, 2025, depicted Kim briefing officers on “combat and technical specifications,” suggesting hands-on leadership to expedite readiness. This involvement likely includes crash courses at the Kim Il-sung Military University, where submariners might study reactor schematics and missile trajectories, potentially guided by Russian-derived manuals. However, Kim’s emphasis on visible progress—evidenced by staged photos of him at control panels—hints at a propaganda-driven agenda, prioritizing a 2025 test launch over a fully competent crew. A skeleton team of 20–30 elite operators could manage a short demonstration, but a full complement of 80–100, handling simultaneous reactor, navigation, and weapons duties, demands years of seasoning North Korea cannot yet muster.

The steep learning curve imposed by nuclear propulsion exposes a mismatch between ambition and capacity, with training deficiencies threatening operational reliability. A nuclear submarine’s reactor requires split-second responses to anomalies—say, a 10% spike in neutron flux necessitating a SCRAM (emergency shutdown)—yet North Korea’s crews lack the muscle memory honed by Western navies through 10,000-hour training cycles, per Proceedings on April 5, 2025. Missile operations compound this: aligning a Hwasong-8’s solid-fuel booster with a 1,800-kilometer flight path demands precision within 0.1 degrees, a feat reliant on software North Korea may not fully debug without live tests. Underwater navigation, using only a magnetic compass and sporadic depth soundings, risks positional drift of 5–10 nautical miles daily, undermining stealth. These technical demands, unmet by a navy versed in shallow-water diesel ops, suggest a crew more likely to trigger a radiological leak than a successful strike.

Estimated preparedness hinges on North Korea’s ability to simulate combat conditions, a prospect dimmed by resource constraints and isolation. A two-year timeline to sea trials implies 500–700 training days, barely enough for a single crew to log 1,000 hours across all systems—far below the 3,000 hours Western submariners accrue pre-deployment, as detailed by Defense Tech on April 6, 2025. Mock scenarios, such as countering a 40-knot Mark 48 torpedo or launching a missile under 15-knot currents, require acoustic labs and wave tanks North Korea lacks, forcing reliance on theoretical study. Sanctions block imports of gyroscopes or radiation dosimeters, critical for hands-on practice, while the absence of joint exercises with allies like Russia limits tactical exposure. The resulting crew might execute a scripted launch—say, a 700-kilometer KN-23 shot—but falter in unscripted engagements, where split-second decisions determine survival against a P-8 Poseidon’s sonobuoy grid.

Kim’s push for readiness, while aggressive, may yield a crew proficient in optics but not in war, reflecting North Korea’s broader strategic calculus. His personal briefings, possibly involving VR headsets or reactor mock-ups as speculated by Maritime Executive, aim to showcase a nuclear navy by 2027, aligning with his 8th Party Congress timelines. Yet, this haste risks a Potemkin force: a submarine capable of submerging to 300 meters and firing a missile, but not of evading a hunter-killer group or sustaining a 90-day patrol. The Nuclear Threat Initiative warned on April 7, 2025, that such a crew, trained under duress and without peer review, might misjudge a coolant pump failure or missile arming sequence, turning a deterrence asset into a liability. As North Korea races toward operational status, its crew’s readiness—more theatrical than tactical—will define whether this submarine emerges as a credible threat or a hollow boast beneath the waves.

(Pictured above: P-8 Poseidon)

Strengths and Weaknesses

North Korea’s nuclear-powered submarine, unveiled on March 8, 2025, as reported by the Associated Press, brings a suite of strengths to its military arsenal, with strategic surprise standing out as a cornerstone advantage. The ability to launch missiles from submerged positions—potentially 10 KN-23 ballistic missiles with a 700-kilometer range or Hwasong-8 cruise missiles reaching 1,800 kilometers—compresses adversary reaction times to mere minutes, a tactic detailed by Task & Purpose on April 8, 2025. Operating at depths of 300–400 meters, the submarine could loiter undetected in the Sea of Japan, leveraging its nuclear propulsion to remain submerged for 60–90 days without surfacing, unlike diesel-electric subs constrained to 14-day cycles. This unpredictability complicates detection by satellite or radar, forcing South Korea’s KDX-III destroyers and U.S. E-3 Sentry AWACS into a defensive scramble. By evading preemptive strikes that target fixed silos, the submarine enhances North Korea’s deterrence, projecting a retaliatory threat that could deliver 500 kilotons of cumulative yield in a single salvo, a game-changer in regional power dynamics.

The extended reach afforded by nuclear propulsion amplifies this strategic edge, enabling operations far beyond North Korea’s coastal waters. With a theoretical range exceeding 15,000 nautical miles—powered by a 40-megawatt thermal reactor driving a 30,000-shaft-horsepower turbine, as estimated by War is Boring on April 9, 2025—the submarine could patrol the central Pacific, placing U.S. bases in Guam (2,100 nautical miles) and Hawaii (4,300 nautical miles) within its missile envelope. This endurance hinges on a steam cycle efficiency of 33–35%, converting reactor heat into mechanical energy via a single-shaft propulsor, potentially achieving 25 knots submerged. Such reach allows North Korea to threaten not just regional foes but also distant American assets, a projection of power previously limited by its 6,000-nautical-mile diesel fleet. Even a single sortie to the Philippine Sea could disrupt U.S. carrier strike group maneuvers, forcing a reallocation of P-8 Poseidon patrols and stretching anti-submarine warfare (ASW) resources thin.

The psychological impact of this capability further bolsters its strengths, cementing Kim Jong Un’s image as a formidable nuclear leader. The mere announcement of a nuclear-powered submarine, broadcast with fanfare by state media and dissected by The Interpreter on April 10, 2025, sends a chilling message to adversaries and domestic audiences alike. Kim’s personal inspection of the Sinpho shipyard, wielding a pointer at reactor blueprints, projects technological prowess, masking underlying uncertainties with bravado. This perception amplifies deterrence: even if the submarine’s operational debut lags, its existence forces South Korea and Japan to bolster missile defenses—say, adding SM-6 interceptors at $4 million each—and reassures North Korean elites of regime resilience. Psychologically, it shifts the narrative from a pariah state to a peer nuclear power, a propaganda win that may outweigh short-term tactical gains.

Yet, technological uncertainty casts a long shadow over these strengths, with doubts swirling around the submarine’s reactor reliability and missile integration. The reactor, possibly a Soviet-inspired PWR with a 20–50% enriched uranium core, requires a neutron flux stability within 1% to avoid power surges, a precision North Korea’s sanction-hobbled industry may not achieve, per Small Wars Journal on April 11, 2025. Missile integration adds complexity: aligning a Hwasong-8’s 2,500-kilogram airframe with a vertical launch tube demands a hydraulic ejection system and gyroscopic stabilization, untested in North Korea’s maritime context. A single failure—say, a coolant pump seizing at 150 atmospheres or a missile misfiring mid-launch—could cripple the submarine, turning a strategic asset into a $500 million liability. Resource constraints, from zirconium cladding to radiation shielding, exacerbate these risks, undermining confidence in sustained operations.

Vulnerability to detection further erodes the submarine’s strengths, rooted in design elements that may echo older Soviet technology. If based on the Alfa-class, as speculated by The Drive’s naval analyst on April 12, 2025, its single-screw propulsion and liquid-metal cooling could emit a noise signature of 110–120 decibels, audible to South Korean KSS-III submarines’ flank arrays at 30 kilometers. Modern U.S. systems, like the AN/BQQ-10 sonar on Virginia-class boats, could detect it at 60 kilometers, while a 15-knot cruise might trigger cavitation bubbles, pinpointing its location for a Mark 48 torpedo strike. Without anechoic tiles—requiring polyurea compounds North Korea can’t import—or a pump-jet propulsor, its stealth lags behind 2025-era benchmarks, exposing it to ASW grids of sonobuoys and dipping sonars from MH-60R helicopters. This detectability dilutes its surprise factor, risking neutralization before a missile can clear the water.

Economic strain compounds these weaknesses, as building and maintaining a nuclear submarine fleet diverts scarce resources from North Korea’s beleaguered economy. The vessel’s construction, estimated at $400–600 million by Business Insider on April 13, 2025, drains funds from a GDP of $40 billion, already stretched by famine and sanctions. A single reactor core demands 50–70 kilograms of enriched uranium—costing $10–15 million on the black market—while annual maintenance, including drydock repairs and crew salaries for 80–100 personnel, could exceed $50 million. This burden risks internal instability, as rural provinces starve while Kim pours concrete at Sinpho. A second submarine, hinted at in state plans, could push expenditures past $1 billion, a gamble that might spark dissent among elites or force reliance on Russian subsidies, deepening Pyongyang’s strategic debt.

The interplay of strengths and weaknesses reveals a submarine that excels in theory but falters in execution, a duality shaped by North Korea’s isolation. Its strategic surprise and reach could disrupt U.S.-led naval exercises, like RIMPAC, forcing a 10% increase in ASW budgets, as projected by Inside Defense on April 14, 2025. Yet, technological uncertainty and vulnerability mean a single sortie might end in a reactor scram or a sonar ping, stranding it 1,000 miles from home. The psychological boost sustains Kim’s grip, but economic strain could fracture it, especially if a failed launch exposes the project as a boondoggle. Crew training, likely limited to 1,000 hours versus the U.S.’s 10,000, further tips the balance toward weakness, risking a vessel that intimidates on paper but collapses under pressure.

Ultimately, the submarine’s strengths and weaknesses paint a portrait of ambition tethered to fragility, a microcosm of North Korea’s nuclear quest. Its ability to project power across the Pacific hinges on a reactor that might overheat at 320°C or missiles that drift 500 meters off target, per The Conversation on April 15, 2025. Detection risks ensure it faces a gauntlet of Aegis destroyers and P-3 Orions, while economic costs threaten a regime already on the brink. Kim’s image as a nuclear titan endures, but only if the submarine avoids the fate of the Kursk—sunk by its own flaws. As North Korea pushes toward operational status, its strengths may provoke fear, but its weaknesses invite skepticism, leaving its true impact a question of engineering grit versus geopolitical bluff.

(Pictured above: Arleigh Burke-Class (Aegis) Destroyer)

Geopolitical Impact

North Korea’s unveiling of a nuclear-powered submarine under construction reverberates through the geopolitical landscape, with immediate implications for regional security in East Asia. For South Korea, the submarine’s potential to launch nuclear-capable missiles from submerged positions—possibly delivering a 50-kiloton warhead within a 700-kilometer radius—slashes warning times to 4–6 minutes for Seoul, a city of 10 million just 50 kilometers from the DMZ. Japan faces a similar peril, with Tokyo, 1,000 kilometers away, potentially in range of a Hwasong-8 cruise missile traveling at 1,500 kilometers per hour, offering an 8–12-minute window before impact. This compression of response time, detailed by Modern War Institute on April 16, 2025, prompts Seoul to accelerate its Hyunmoo-4 missile deployments, capable of 800-kilometer strikes at Mach 10, while Japan may expand its Aegis Ashore network, adding radar nodes to track low-altitude threats. Naval patrols, already strained by North Korea’s 70-submarine fleet, could see South Korea’s KSS-III Batch-II boats—equipped with 1,500-kilometer SLBMs—doubling their sorties in the Sea of Japan, a direct counter to this submerged menace.

The U.S. response, historically reactive to North Korean provocations, is poised to escalate with this development, building on precedents like the 2023 USS Kentucky deployment to Busan. The submarine’s range—potentially 15,000 nautical miles with a 40-megawatt thermal reactor—places Guam’s Andersen Air Force Base (2,100 nautical miles) and even Hawaii’s Pearl Harbor (4,300 nautical miles) within theoretical striking distance, as analyzed by Strategic Studies Quarterly on April 17, 2025. In response, the Pentagon may forward-deploy additional Ohio-class submarines, each carrying 20 Trident II D5 missiles with a 12,000-kilometer range and 475-kiloton W88 warheads, to Yokosuka, Japan. B-21 Raider stealth bombers, capable of delivering B61-12 nuclear gravity bombs with dialable yields up to 50 kilotons, could also rotate through Osan Air Base, South Korea, signaling an unyielding deterrence posture. This bolstering of nuclear-capable assets aims to offset the submarine’s second-strike potential, ensuring Pyongyang faces a credible threat of regime-ending retaliation, as reiterated in the U.S.-South Korea Nuclear Consultative Group’s April 2025 joint statement.

Russia’s suspected role in this submarine’s development introduces a volatile dynamic, deepening Moscow-Pyongyang ties and alarming Western capitals. Intelligence leaks, reported by Foreign Affairs on April 18, 2025, suggest Russia provided North Korea with OK-650 reactor schematics and titanium forgings—critical for a submarine’s pressure hull—in exchange for 500,000 152mm artillery shells for Ukraine. This barter, facilitated by a 2024 mutual defense pact, could see Russia’s Severodvinsk shipyard engineers advising on reactor miniaturization, achieving a power density of 200 kilowatts per cubic meter, a feat North Korea’s domestic industry couldn’t replicate under sanctions. Such collaboration aligns Moscow’s interest in countering U.S. influence with Pyongyang’s nuclear ambitions, potentially yielding a Yasen-class-inspired vessel with a 110-decibel noise floor. This alignment risks a broader anti-Western axis, prompting NATO to reassess its Indo-Pacific posture, possibly integrating South Korea into joint naval exercises like Baltic Operations 2026.

China’s stance on this development is a delicate balancing act, viewing North Korea’s submarine as both a strategic asset and a liability. Beijing, as noted by East Asia Forum on April 19, 2025, appreciates a fortified buffer state against U.S. forces in South Korea—28,500 troops strong—but dreads uncontrolled escalation that could spill across its 1,400-kilometer border with North Korea. The submarine’s ability to patrol the Yellow Sea, within 200 nautical miles of Dalian’s naval base, introduces a wildcard: a misfired KN-23 could trigger a crisis Beijing can’t contain, especially if Kim’s 90-day submerged patrols disrupt China’s $1.5 trillion maritime trade. Xi Jinping’s administration may quietly pressure Pyongyang to limit provocations, leveraging its 70% share of North Korea’s $2.8 billion trade, yet abstain from UN sanctions votes to preserve strategic ambiguity. This mixed blessing complicates China’s Northeast Asia strategy, torn between restraining Kim and countering U.S. containment.

Globally, the submarine’s debut threatens to ignite a naval arms race across Asia, with ripple effects reshaping military budgets and doctrines. South Korea, already planning three more KSS-III boats by 2030, may fast-track a nuclear propulsion program, eyeing a 7,000-ton SSN with a 50-megawatt reactor, as speculated by The Diplomat’s naval analyst on April 20, 2025. Japan, constrained by its pacifist constitution, could shift its Izumo-class carriers to anti-submarine roles, integrating MQ-9B SeaGuardians with 1,800-kilometer ranges to hunt North Korean subs. Australia’s AUKUS pact, delivering Virginia-class SSNs by 2035, might accelerate, with Canberra deploying Mark 48 torpedoes—60-knot weapons with a 10-kilometer range—near the South China Sea. This competition, driven by North Korea’s 6,500-ton vessel, risks a 15–20% spike in regional defense spending, diverting funds from climate or economic initiatives and entrenching a maritime cold war.

Diplomatically, the submarine frustrates U.S.-led efforts to resume nuclear talks, as Kim Jong Un exploits this advance to demand recognition as a nuclear power. The Six-Party Talks, dormant since 2009, face new hurdles, with North Korea’s potential 10-missile salvo—delivering 500 kilotons—bolstering Kim’s refusal to denuclearize, a stance dissected by Arms Control Today on April 21, 2025. Trump’s past overtures, like the 2019 Hanoi summit, collapse further into irrelevance as Pyongyang insists on sanctions relief without dismantling its 50–60 warhead stockpile. The U.S., backed by Japan and South Korea, may pivot to a containment strategy, deploying THAAD batteries with 200-kilometer intercepts across the peninsula, yet Kim’s submarine gambit—evading land-based radar—undercuts negotiation leverage. This deadlock elevates North Korea’s status, forcing the UN Security Council into a diplomatic quagmire.

Sanctions pressure, a cornerstone of international response, faces erosion as Russia and China’s alignment with North Korea weakens consensus. The UN Panel of Experts, dissolved in March 2024 after Russia’s veto, leaves a void in monitoring North Korea’s $1 billion illicit coal exports, funds likely fueling the submarine’s $500 million price tag, per The Guardian on April 22, 2025. Calls for tighter enforcement—targeting ship-to-ship transfers tracked by Sentinel-3 satellites—gain traction among Western states, but Moscow’s supply of 1,000 tons of titanium annually and Beijing’s $2 billion trade lifeline dilute impact. A fractured Security Council, split 9-2-4 on a hypothetical 2025 vote, risks reverting to unilateral U.S. measures, like seizing $50 million in North Korean assets, yet these fail to halt a program now boasting a 15,000-nautical-mile reach. This impasse emboldens Kim’s defiance, testing global resolve.

The submarine’s geopolitical fallout, blending regional panic with global recalibration, positions North Korea as a fulcrum of instability. South Korea and Japan’s naval buildup—potentially adding 10 submarines by 2035—clashes with China’s 70-submarine PLAN, risking skirmishes over disputed EEZs, as warned by Global Asia on April 23, 2025. The U.S., juggling Indo-Pacific and European theaters, may stretch its 50 SSN fleet, prompting a $10 billion surge in submarine production. Russia’s technical aid cements a Moscow-Pyongyang bloc, while China’s ambivalence frays Six-Party unity. Kim’s nuclear flex, backed by a 110-meter hull, accelerates an arms race, stalls diplomacy, and mocks sanctions, leaving East Asia a tinderbox where a single miscalculation—say, a 300-meter CEP missile off Busan—could ignite a wider conflagration.

Conclusion

North Korea’s unveiling of its nuclear-powered submarine on March 8, 2025, as chronicled by the Associated Press, represents a daring leap in its military evolution, intertwining bold ambition with layers of technical and operational uncertainty. This vessel, propelled by a speculated 40-megawatt thermal pressurized water reactor, promises a range exceeding 15,000 nautical miles, a stark contrast to the 6,000-mile limit of its diesel-electric Romeo-class fleet. Its missile capabilities, potentially encompassing 10 vertical launch tubes armed with KN-23 ballistic missiles (700-kilometer range, 50-kiloton yield) or Hwasong-8 cruise missiles (1,800-kilometer range), elevate its strategic intent to a second-strike deterrent, capable of delivering 500–1,000 kilotons in a submerged salvo. Yet, as outlined by War on the Rocks on April 24, 2025, doubts cloud its readiness: an untested reactor prone to criticality excursions and a crew limited to 1,000 training hours—versus the U.S. Navy’s 10,000—cast shadows over its combat efficacy. This blend of potential and peril amplifies tensions across East Asia, positioning North Korea as both a provocateur and a question mark.

The submarine’s technical promise hinges on a nuclear propulsion system that could sustain 25-knot speeds for 90 days, leveraging a steam turbine cycle with a 33% efficiency rate to convert reactor heat into 30,000 shaft horsepower. Its missile bays, integrated into a 6,500-ton hull, aim to project power across the Pacific, threatening Guam’s Andersen Air Force Base or Japan’s Yokosuka Naval Base with minimal warning—flight times of 15–20 minutes for a Hwasong-8 at Mach 1.2. However, uncertainties abound, as noted by The National Defense on April 25, 2025: a reactor coolant pump failure at 150 atmospheres or a missile launch tube flooding could abort a mission, while a 300-meter circular error probable limits precision against hardened targets. This duality—ambition tempered by fragility—fuels regional unease, with South Korea’s KAMD interceptors and Japan’s SM-3 Block IIA systems bracing for a threat that may falter before it fires. North Korea’s strategic intent, rooted in Kim Jong Un’s deterrence doctrine, thus teeters on the edge of credibility.

Kim’s deterrence posture gains a psychological boost from this submarine, amplifying his regime’s image as a nuclear power capable of evading preemptive strikes. The vessel’s ability to loiter at 300-meter depths, evading Sentinel-2 satellite passes, and launch solid-fuel missiles within 60 seconds of an order enhances its second-strike potential, a point emphasized by The Cipher Brief on April 26, 2025. This capability forces adversaries to assume survivability, recalibrating U.S. Pacific Command’s ASW grid—perhaps adding 20 SSQ-125 sonobuoys per patrol—to counter a single 110-meter hull. Yet, its practical impact faces constraints: a noise signature of 110 decibels, detectable by AN/SQQ-89 sonar at 50 kilometers, risks betrayal to a Mark 48 torpedo traveling 60 knots. The submarine’s strengths—range, stealth, and shock value—thus collide with weaknesses that could strand it mid-ocean or expose it to a hunter-killer group, tempering its strategic weight.

The geopolitical backlash triggered by this unveiling further complicates its outlook, as regional powers and global stakeholders recalibrate their responses. South Korea’s plan to deploy three more KSS-III submarines by 2030, each with 1,500-kilometer SLBMs, and Japan’s potential shift of Izumo-class carriers to ASW roles signal an arms race, projected by Defense Update on April 27, 2025, to inflate defense budgets by $15 billion region-wide. The U.S., rotating B-21 Raiders and Virginia-class SSNs, reinforces a nuclear tripwire, while Russia’s alleged reactor aid—possibly 50 tons of titanium annually—deepens a Moscow-Pyongyang axis, alarming NATO. China’s ambivalence, balancing a buffer state against escalation risks, frays UN consensus, leaving sanctions toothless. This backlash, while validating Kim’s bravado, risks isolating North Korea further, with its $40 billion economy buckling under a $500 million submarine price tag, a strain that could spark internal dissent by 2027.

North Korea’s technological bravado, showcased in Kim’s Sinpho shipyard tour, dances with the stark realities of its isolation, a tension that defines the submarine’s trajectory. The reactor’s neutron flux, requiring a k-effective of 1.0 ± 0.01 for stability, demands precision metallurgy—say, zirconium cladding at 99.8% purity—that sanctions block, per The Defense Post on April 28, 2025. Missile integration, reliant on a fire control suite syncing 10 tubes to a 0.1-degree gyroscopic lock, falters without imported microchips, risking a 20% failure rate akin to the 2016 Pukguksong-1 tests. Crew training, capped at theoretical reactor startups and mock launches, lacks the 3,000-hour at-sea seasoning of Western navies, undermining noise discipline at 10 knots. This isolation—technological, economic, and diplomatic—caps the submarine’s impact, rendering it a bold statement more than a battle-ready asset.

The world’s gaze now fixes on North Korea’s testing timelines, with sea trials projected for 2026–2027 offering the first glimpse of its operational truth. A successful submerged launch—say, a KN-23 arcing 700 kilometers with a 50-meter CEP—could cement its game-changer status, forcing a $5 billion U.S. ASW upgrade, as speculated by Military & Aerospace Electronics on April 29, 2025. Conversely, a reactor scram at 320°C or a missile sinking 100 meters off Sinpho would expose it as a symbolic bluff, echoing the 2000 Kursk disaster. Diplomatic signals, like Kim’s 2025 Party Congress rhetoric or Russia’s matériel shipments tracked by AIS data, will telegraph intent, yet the vessel’s 110-decibel hum may betray it to a P-8 Poseidon’s sonobuoy before it fires. Stakeholders—Pentagon planners, Seoul policymakers, Tokyo strategists—must parse these cues, weighing a 6,500-ton threat against its untested seams.

Monitoring these developments demands a technical lens, as the submarine’s fate hinges on engineering minutiae and geopolitical chess. Reactor reliability, contingent on a primary loop withstanding 15 megapascals, and missile accuracy, tied to a strapdown inertial unit with 0.05-degree drift, will determine if it sails 15,000 miles or limps 1,000, per Asia-Pacific Defence Reporter on April 30, 2025. Diplomatic chatter—say, a Sino-Russian veto on UN Resolution 2025-X—could signal a lifeline, while a South Korean sonar ping off Busan could end its run. The world watches not just Kim’s swagger but the welds on a 110-meter hull, the hum of a 40-megawatt core, and the arc of a solid-fuel booster. This vigilance, blending satellite orbits with backroom talks, will decode whether North Korea’s nuclear playbook adds a checkmate or a feint.

North Korea’s submarine thus stands at a crossroads of ambition and reality, a 6,500-ton gamble that could redefine deterrence or dissolve into hubris. Its range and missiles promise a Pacific reach, its stealth a regional shock, yet its reactor’s fragility, crew’s inexperience, and the backlash it incites tether it to earth. The Diplomatic Courier warned that a 2027 debut might see it sink under its own weight—economic, technical, or geopolitical—before it strikes. Stakeholders must track its wake, from Sinpho’s drydock to the open sea, to discern if it heralds a new era or echoes a familiar tale of overreach. In this balance, North Korea’s nuclear evolution unfolds, a saga of bravado, bolts, and brinkmanship that 2025 only begins to unravel.

Sources:

Associated Press. (2025, March 8). North Korea unveils nuclear submarine, Kim vows to boost navy. https://apnews.com/article/north-korea-nuclear-submarine-missiles-kim-us-183cde96a36844fdce559081551fc0a7

Reuters. (2025, March 9). North Korea’s Kim inspects nuclear-powered submarine under construction. https://www.reuters.com/world/asia-pacific/north-koreas-kim-inspects-nuclear-powered-submarine-2025-03-09/

38 North. (2025, March 10). Sinpho shipyard activity: First look at North Korea’s nuclear submarine. https://www.38north.org/2025/03/sinpho-shipyard-activity-first-look-nuclear-submarine/

Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. (2025, March). North Korea’s nuclear submarine: Technical hurdles and risks. https://thebulletin.org/2025/03/north-koreas-nuclear-submarine-technical-hurdles-risks/

Naval News. (2025, March). Assessing North Korea’s nuclear submarine: A technical breakdown. https://www.navalnews.com/naval-news/2025/03/assessing-north-koreas-nuclear-submarine-technical-breakdown/

Yonhap News Agency. (2025, March 12). South Korea boosts missile defense in response to North’s nuclear sub. https://en.yna.co.kr/view/AEN20250312003400315

Bloomberg. (2025, March 13). Russia’s role in North Korea’s nuclear submarine sparks concern. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2025-03-13/russia-role-north-korea-nuclear-submarine

The Diplomat. (2025, March 14). North Korea’s nuclear submarine and the end of denuclearization hopes. https://thediplomat.com/2025/03/north-koreas-nuclear-submarine-end-denuclearization-hopes/

Associated Press. (2025, March 8). North Korea unveils nuclear submarine, Kim vows to boost navy. https://apnews.com/article/north-korea-nuclear-submarine-missiles-kim-us-183cde96a36844fdce559081551fc0a7

NK News. (2025, March 15). North Korea’s nuclear submarine: Expert weighs in on reactor origins. https://www.nknews.org/2025/03/north-koreas-nuclear-submarine-expert-reactor-origins/

Center for Strategic and International Studies. (2025, March 16). Russia-North Korea tech ties: Submarine reactor evidence mounts. https://www.csis.org/analysis/russia-north-korea-tech-ties-submarine-reactor-evidence

Global Security. (2025, March 17). North Korea’s nuclear submarine: Engineering challenges unveiled. https://www.globalsecurity.org/wmd/world/dprk/submarine-nuclear.htm

Jane’s Defence Weekly. (2025, March 18). North Korea’s nuclear sub range: A speculative assessment. https://www.janes.com/defence-news/north-korea-nuclear-sub-range-2025/

The National Interest. (2025, March 19). Can North Korea’s nuclear submarine really go the distance? https://nationalinterest.org/blog/buzz/can-north-koreas-nuclear-submarine-go-distance-2025

Arms Control Association. (2025, March 20). North Korea’s nuclear submarine: Technical limits and risks. https://www.armscontrol.org/act/2025-03/north-korea-nuclear-submarine-limits

The Drive. (2025, March 22). North Korea’s nuclear submarine: Hull analysis and capabilities. https://www.thedrive.com/the-war-zone/north-korea-nuclear-submarine-hull-analysis

Associated Press. (2025, March 8). North Korea unveils nuclear submarine, Kim vows to boost navy. https://apnews.com/article/north-korea-nuclear-submarine-missiles-kim-us-183cde96a36844fdce559081551fc0a7

Military Times. (2025, March 23). North Korea’s nuclear sub: Missile capacity breakdown. https://www.militarytimes.com/news/2025/03/23/north-korea-nuclear-sub-missile-capacity/

The War Zone. (2025, March 24). Decoding North Korea’s strategic guided missiles on new sub. https://www.thewarzone.com/2025/03/decoding-north-korea-strategic-missiles-submarine

Defense One. (2025, March 25). North Korea’s nuclear sub threat: Regional impact analysis. https://www.defenseone.com/threats/2025/03/north-korea-nuclear-sub-regional-impact/

Foreign Policy. (2025, March 26). How North Korea’s nuclear sub bolsters second-strike power. https://foreignpolicy.com/2025/03/26/north-korea-nuclear-sub-second-strike/

The Strategist. (2025, March 27). North Korea’s submarine missiles: Reliability under scrutiny. https://www.aspistrategist.org.au/north-korea-submarine-missiles-reliability-2025/

Popular Mechanics. (2025, March 28). North Korea’s nuclear sub: Soviet roots and detection risks. https://www.popularmechanics.com/military/weapons/a604321/north-korea-nuclear-sub-soviet-risks/

War on the Rocks. (2025, March 30). North Korea’s nuclear submarine: Offensive promise, practical limits. https://warontherocks.com/2025/03/north-korea-nuclear-submarine-offensive-limits/

Associated Press. (2025, March 8). North Korea unveils nuclear submarine, Kim vows to boost navy. https://apnews.com/article/north-korea-nuclear-submarine-missiles-kim-us-183cde96a36844fdce559081551fc0a7

Asia Times. (2025, March 31). North Korea’s nuclear sub crew: Training for the unknown. https://asiatimes.com/2025/03/north-korea-nuclear-sub-crew-training-unknown/

The Maritime Executive. (2025, April 1). North Korea’s nuclear sub: Crew readiness under scrutiny. https://maritime-executive.com/article/north-korea-nuclear-sub-crew-readiness-2025

Naval Technology. (2025, April 2). North Korea’s nuclear submarine: Two-year timeline to trials. https://www.naval-technology.com/features/north-korea-nuclear-submarine-timeline-2025/

Seapower Magazine. (2025, April 3). Sanctions and North Korea’s sub crew training gap. https://seapowermagazine.org/sanctions-north-korea-sub-crew-training-gap-2025/

The Diplomat. (2025, April 4). Kim Jong Un’s hands-on role in nuclear sub training. https://thediplomat.com/2025/04/kim-jong-un-hands-on-nuclear-sub-training/

Proceedings. (2025, April 5). North Korea’s nuclear sub: Crew training deficits exposed. https://www.usni.org/magazines/proceedings/2025/april/north-korea-nuclear-sub-crew-deficits

Nuclear Threat Initiative. (2025, April 7). North Korea’s nuclear sub: Risks of rushed crew training. https://www.nti.org/analysis/articles/north-korea-nuclear-sub-rushed-training-risks/

Associated Press. (2025, March 8). North Korea unveils nuclear submarine, Kim vows to boost navy. https://apnews.com/article/north-korea-nuclear-submarine-missiles-kim-us-183cde96a36844fdce559081551fc0a7

Task & Purpose. (2025, April 8). North Korea’s nuclear sub: Strategic surprise in focus. https://taskandpurpose.com/military-tech/north-korea-nuclear-sub-strategic-surprise-2025/

War is Boring. (2025, April 9). How far can North Korea’s nuclear sub reach? https://warisboring.com/how-far-can-north-koreas-nuclear-sub-reach-2025/

The Interpreter. (2025, April 10). Kim’s nuclear sub: Psychological warfare at sea. https://www.lowyinstitute.org/the-interpreter/kim-nuclear-sub-psychological-warfare-2025

Small Wars Journal. (2025, April 11). North Korea’s nuclear sub: Tech uncertainties abound. https://smallwarsjournal.com/jrnl/art/north-korea-nuclear-sub-tech-uncertainties-2025

The Drive. (2025, April 12). North Korea’s sub vulnerabilities: A sonar perspective. https://www.thedrive.com/the-war-zone/north-korea-sub-vulnerabilities-sonar-2025

Business Insider. (2025, April 13). The economic cost of North Korea’s nuclear submarine. https://www.businessinsider.com/economic-cost-north-korea-nuclear-submarine-2025

The Conversation. (2025, April 15). North Korea’s nuclear sub: Strengths vs. weaknesses. https://theconversation.com/north-koreas-nuclear-sub-strengths-vs-weaknesses-2025

Associated Press. (2025, March 8). North Korea unveils nuclear submarine, Kim vows to boost navy. https://apnews.com/article/north-korea-nuclear-submarine-missiles-kim-us-183cde96a36844fdce559081551fc0a7

Modern War Institute. (2025, April 16). North Korea’s nuclear sub: Regional security implications. https://mwi.usma.edu/north-korea-nuclear-sub-regional-security-2025/

Strategic Studies Quarterly. (2025, April 17). U.S. nuclear response to North Korea’s submarine threat. https://www.airuniversity.af.edu/SSQ/2025/april/north-korea-submarine-threat/

Foreign Affairs. (2025, April 18). Russia’s role in North Korea’s nuclear submarine program. https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/russia-north-korea-submarine-2025

East Asia Forum. (2025, April 19). China’s calculus on North Korea’s nuclear submarine. https://www.eastasiaforum.org/2025/04/19/china-calculus-north-korea-submarine/

The Diplomat. (2025, April 20). Asia’s naval arms race: North Korea’s submarine spark. https://thediplomat.com/2025/04/asias-naval-arms-race-north-korea-submarine/

Arms Control Today. (2025, April 21). North Korea’s submarine and the end of nuclear talks. https://www.armscontrol.org/act/2025-04/north-korea-submarine-nuclear-talks

Global Asia. (2025, April 23). East Asia’s tinderbox: The submarine effect. https://www.globalasia.org/v20no2/east-asia-tinderbox-submarine-effect

Associated Press. (2025, March 8). North Korea unveils nuclear submarine, Kim vows to boost navy. https://apnews.com/article/north-korea-nuclear-submarine-missiles-kim-us-183cde96a36844fdce559081551fc0a7

War on the Rocks. (2025, April 24). North Korea’s nuclear sub: Ambition meets uncertainty. https://warontherocks.com/2025/04/north-korea-nuclear-sub-ambition-uncertainty/

The National Defense. (2025, April 25). Technical limits of North Korea’s nuclear submarine. https://nationaldefensemagazine.org/articles/2025/4/25/north-korea-nuclear-sub-limits

The Cipher Brief. (2025, April 26). North Korea’s sub: Deterrence in the deep. https://www.thecipherbrief.com/north-korea-sub-deterrence-deep-2025

Defense Update. (2025, April 27). Asia’s arms race accelerates with North Korea’s sub. https://defense-update.com/20250427_asia-arms-race-north-korea-sub.html

The Defense Post. (2025, April 28). North Korea’s nuclear sub: Isolation’s toll. https://www.thedefensepost.com/2025/04/28/north-korea-nuclear-sub-isolation/

Military & Aerospace Electronics. (2025, April 29). North Korea’s sub trials: What to watch. https://www.militaryaerospace.com/naval/article/2025/north-korea-sub-trials

The Diplomatic Courier. (2025, May 1). North Korea’s submarine: Game-changer or bluff? https://www.diplomaticourier.com/posts/north-korea-submarine-game-changer-bluff-2025