Submarine Showdown: Comparing Chinese and American Capabilities and Their Geopolitical Stakes in the South China Sea

South China Sea Standoff: The Submarine Edge That Could Decide It All

TL;DR:

U.S. submarines lead in stealth (sub-100 dB), sensors (AN/BQQ-10, 50 nm range), and weapons (Tomahawks, Mk 48 torpedoes), with decades of Cold War-honed experience.

China’s fleet, mixing diesel-electric Yuan-class (110 dB, AIP) and nuclear Shang/Jin-class, grows rapidly (60-70 subs), optimized for South China Sea’s shallow waters.

U.S. doctrine focuses on global power projection; China emphasizes regional denial (A2/AD), leveraging geography like reefs and chokepoints.

In the South China Sea, U.S. subs secure sea lanes and deter China’s outposts, while Chinese subs challenge FONOPs, though struggle to detect U.S. stealth.

By 2030, China’s Type 095/096 subs may close the tech gap, but U.S. experience and innovation (e.g., SSN(X), hypersonics) aim to maintain dominance.

And Now for the Deep Dive…

Introduction

Submarines have emerged as silent titans in the escalating U.S.-China rivalry, and nowhere is their role more pivotal than in the contested waters of the South China Sea. Imagine a moonless night in early 2025: a U.S. Virginia-class submarine, lurking at periscope depth, tracks a Chinese Type 039A Yuan-class boat weaving through the Spratly Islands’ shallow reefs. The tension is palpable yet invisible, a chess game played beneath the waves where a single misstep could ripple into open conflict. The South China Sea, a 1.4-million-square-mile expanse, is not just a geopolitical flashpoint but an economic lifeline, channeling over $3 trillion in annual trade through chokepoints like the Malacca Strait. Here, the United States and China flex their naval might, with submarines serving as stealthy arbiters of power. The differences between their underwater fleets—rooted in cutting-edge technology, decades of operational experience, and divergent strategic doctrines—define their ability to deter, dominate, or disrupt in this volatile theater. This article dives deep into the technical and experiential disparities between American and Chinese submarine forces, exploring how these factors shape their geopolitical leverage and battlefield potential in a region teetering on the edge of confrontation.

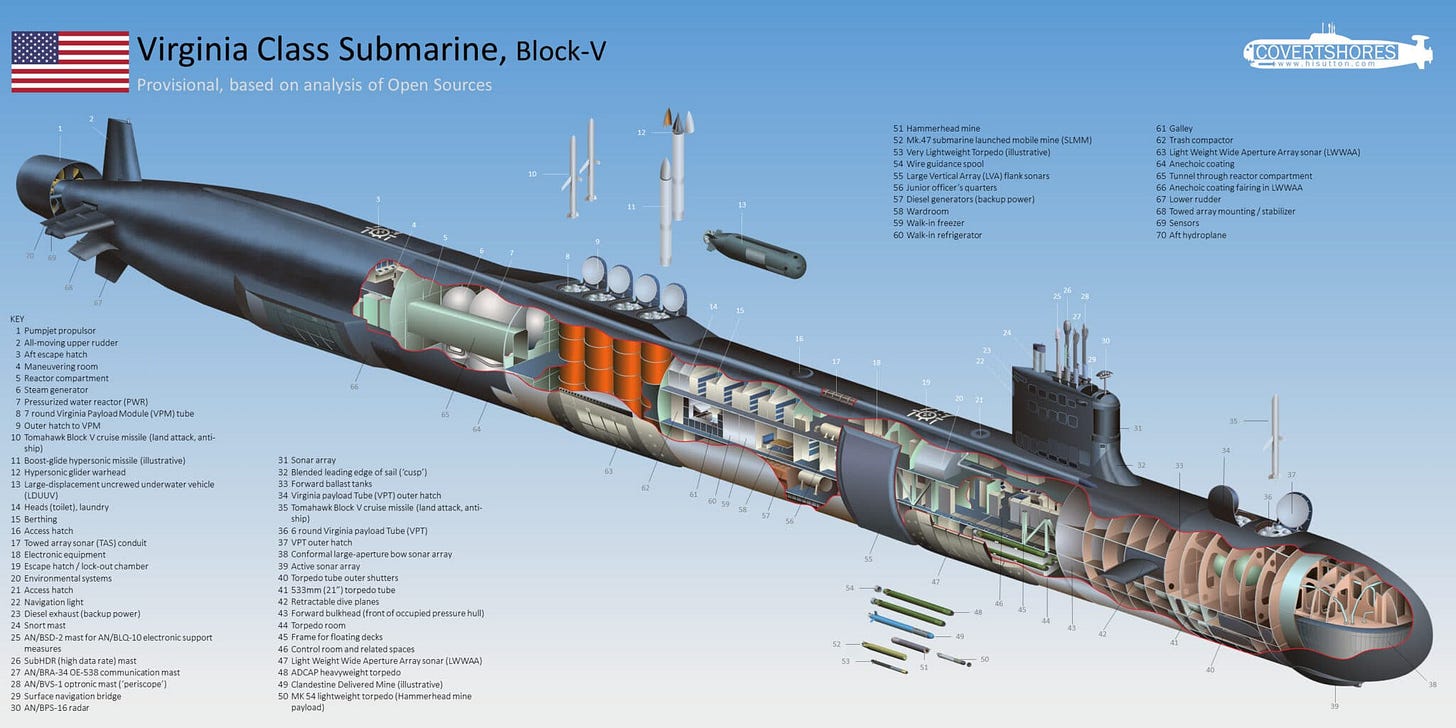

The American submarine fleet stands as a technological marvel, honed by decades of refinement and a Cold War legacy of underwater supremacy. As of early 2025, the U.S. Navy operates 67 nuclear-powered submarines, including 32 Virginia-class attack boats (SSNs), 14 Ohio-class ballistic missile submarines (SSBNs), and a dwindling handful of Los Angeles-class relics. The Virginia-class, with its Block V iteration now deploying, boasts an AN/BQQ-10(V) sonar suite paired with large-aperture bow arrays, offering unmatched acoustic detection in noisy littoral waters. Its quieting technology—featuring anechoic coatings and pump-jet propulsors—renders it nearly imperceptible, even to advanced hydrophones. Armed with Mk 48 ADCAP torpedoes, Tomahawk Block V missiles (capable of hypersonic upgrades), and Vertical Launch Systems carrying 40 munitions, these submarines excel in multi-domain warfare, from anti-submarine hunts to precision strikes on land targets. The U.S. operational edge is equally formidable: crews train relentlessly in exercises like RIMPAC, simulating complex Pacific scenarios, and draw on a doctrine refined through tracking Soviet subs across the Atlantic. Yet, this prowess comes at a cost—each Virginia-class hull exceeds $3.6 billion, and maintenance backlogs stretch deployment cycles thin, a vulnerability as China’s fleet swells. In the South China Sea, where deep-water access meets shallow shelves, America’s nuclear-powered giants must adapt to a theater less suited to their blue-water DNA, relying on networked integration with P-8 Poseidon aircraft and MQ-4C Triton drones to maintain dominance.

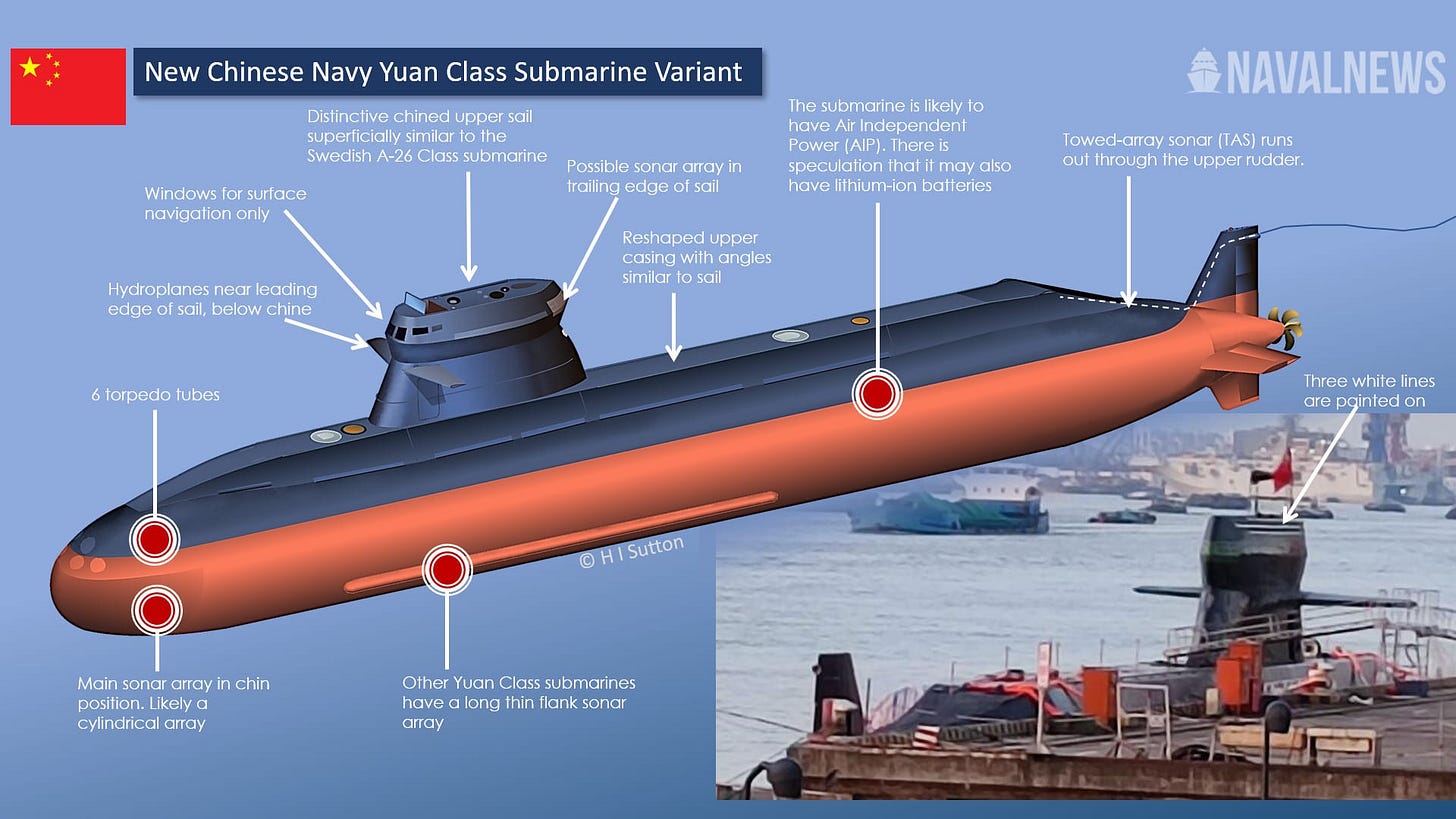

China’s submarine force, by contrast, reflects a rapid ascent fueled by ambition and regional focus, though it trails the U.S. in raw sophistication. The People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) commands roughly 66 submarines in 2025, a mix of diesel-electric and nuclear-powered platforms, with projections of reaching 76 by 2030 according to the Pentagon’s latest assessment. The Type 039A Yuan-class, numbering over 20, leverages air-independent propulsion (AIP) with Stirling engines, extending submerged endurance to three weeks and silencing its signature in the South China Sea’s cluttered acoustics—ideal for ambushes near disputed reefs. Nuclear options like the Type 093B Shang-class, with its vertical launch tubes for YJ-18 supersonic anti-ship missiles (range: 540 km), signal China’s push into oceanic deterrence, though noise levels remain a generational step behind U.S. benchmarks, with shaft-rate tones detectable by towed arrays like the TB-29A. The Type 094 Jin-class SSBNs, armed with JL-3 ballistic missiles (range: 12,000 km), bolster Beijing’s second-strike nuclear posture, yet their reactor hum compromises stealth. China’s experience is shallower: lacking the U.S.’s combat-hardened pedigree, PLAN crews rely on intensified patrols—such as a 2024 Indian Ocean sortie tracked by U.S. satellites—and simulations to bridge the gap. Doctrine centers on anti-access/area denial (A2/AD), using submarines to choke sea lanes and shield artificial islands, a strategy tailor-made for the South China Sea’s labyrinthine geography but untested in all-out war.

These disparities in capability and experience cast long shadows over the South China Sea’s geopolitical and battlefield landscape. The U.S. wields its submarines as tools of global deterrence and power projection, safeguarding freedom of navigation and reassuring allies like Japan and the Philippines amid China’s reef fortifications. A single Virginia-class boat, lurking beyond the 12-nautical-mile line of Fiery Cross Reef, can disrupt PLAN logistics with a Tomahawk salvo, while Ohio-class SSBNs in the Philippine Sea underwrite nuclear stability. China, meanwhile, counters with a defensive-offensive hybrid: its Yuan-class subs, quieter in shallow waters than nuclear counterparts, could stalk U.S. carrier strike groups, loosing YJ-18s to blunt American intervention in a Taiwan crisis. Geopolitically, this underwater duel fuels escalation risks—submarine shadowing incidents, like the 2023 near-collision reported off Scarborough Shoal, test diplomatic restraint. On the battlefield, the stakes hinge on control versus denial: U.S. submarines aim to secure sea lines of communication, while China’s seek to sever them, leveraging proximity and numbers. By 2030, as China’s Type 095 SSNs and Type 096 SSBNs—touted for pump-jet drives and acoustic cladding—enter service, the technological gap may narrow, challenging U.S. primacy. For now, America’s edge in experience and integration holds, but the South China Sea remains a proving ground where stealth, not strength, may decide the victor.

(Pictured above: Tomahawk Block V missile)

Overview of Submarine Warfare in Modern Geopolitics

Submarine warfare has ascended to a pivotal role in modern geopolitics, serving as the unseen backbone of naval strategy in an era where surface ships face mounting threats from hypersonic missiles and swarming drones. These vessels leverage stealth through advanced acoustic quieting—think anechoic tiles absorbing sonar pings and pump-jet propulsors minimizing cavitation noise—enabling them to conduct intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR) missions undetected. Equipped with hydrophones like the U.S. AN/BQQ-10 or China’s towed array systems, submarines passively harvest signals intelligence, from enemy radar emissions to underwater communications, while their periscopes and photonic masts capture visual data in contested littorals. Beyond espionage, they project power across vast distances: nuclear-powered ballistic missile submarines (SSBNs) like the American Ohio-class carry Trident II D5 missiles with a 12,000-kilometer range, ensuring second-strike nuclear deterrence, while attack submarines (SSNs) deploy precision munitions—Tomahawks with 2,500-kilometer reach or YJ-18s with 540 kilometers—to neutralize shore installations or enemy fleets. In the duel for sea control and denial, submarines dictate maritime outcomes by severing supply lines or sinking carriers, their submerged autonomy rendering them immune to most air-based threats as of early 2025.

The South China Sea emerges as a singular proving ground for this underwater chess game, its complex hydrography amplifying the submarine’s tactical edge. Covering 1.4 million square miles, the region juxtaposes shallow shelves—averaging 70 meters deep near the Spratlys—with abyssal depths exceeding 5,000 meters near the Luzon Strait, creating a sonar-scattering playground of thermoclines and salinity gradients. These conditions degrade active sonar performance, like that of the SQS-53C hull-mounted arrays on U.S. destroyers, while rewarding passive detection by quieter platforms suited to ambush tactics. Strategic chokepoints, notably the Malacca Strait—handling 80% of China’s oil imports and 60 million barrels daily—elevate the stakes, as a single submarine could throttle this artery with torpedoes or mines. China’s militarized reefs, such as Fiery Cross with its 3,000-meter runway and sonar installations, extend this dynamic, forming a networked anti-submarine warfare (ASW) grid that challenges intruders. Yet, the shallow waters—often less than 200 meters—constrain deep-diving nuclear submarines, favoring diesel-electric boats with air-independent propulsion (AIP) that can linger silently on battery power for weeks, a nuance shaping the U.S.-China naval balance as of February 2025.

The U.S.-China rivalry in this theater casts submarines as a decisive metric of naval power, transcending the visibility of carrier strike groups or fifth-generation fighters. America’s submarine fleet, all nuclear-powered, boasts 67 hulls in 2025, including the Virginia-class Block V with its 28-meter payload module for 40 vertical-launch munitions, a testament to its blue-water dominance honed against Soviet foes. China counters with a mixed fleet of 66 boats, blending diesel-electric Type 039A Yuans—equipped with Stirling AIP for 8,000-nautical-mile endurance—and nuclear Type 093B Shangs, signaling a shift toward oceanic reach. This rivalry isn’t just about numbers; it’s a clash of technological paradigms and operational doctrines, with submarines underpinning deterrence and coercion. The U.S. leverages its subs to patrol sea lanes and shadow PLAN movements, while China uses its fleet to enforce its Nine-Dash Line claims, deploying them as an anti-access/area denial (A2/AD) shield. By early 2025, incidents like Chinese subs trailing U.S. carriers near Scarborough Shoal underscore this submerged standoff, amplifying tensions alongside surface and air forces.

Technological disparities further define this underwater contest, with implications rippling through the South China Sea’s strategic calculus. The U.S. maintains a lead in acoustic stealth—Virginia-class boats achieve noise levels below 100 decibels, thanks to S9G reactor isolation and shaft dampening—paired with the AN/WSQ-11 combat system integrating real-time satellite feeds. China’s Yuan-class, while quieter than its nuclear siblings at 110 decibels with AIP engaged, relies on less sophisticated Type 366 sonar, limiting detection range against U.S. towed arrays like the TB-29A. Weaponry widens the gap: America’s Mk 48 ADCAP torpedoes, with 650-kilogram warheads and 50-kilometer range, outclass China’s Yu-6 at 45 kilometers, while Tomahawk upgrades promise hypersonic variants by 2026. Yet, China’s sheer numbers and regional proximity—bolstered by shore-based DF-21D missile support—offset some deficits, especially in a theater where shallow waters blunt deep-diving U.S. advantages. As both nations eye 2030, with China’s quieter Type 095 SSNs looming, the technological race intensifies, reshaping deterrence in this maritime crucible.

Geopolitically, submarines in the South China Sea are linchpins in a high-stakes game of influence and escalation. For the U.S., they uphold freedom of navigation, their presence near Subi Reef deterring PLAN overreach and reassuring allies like Vietnam and the Philippines, who face Chinese fishing militia incursions. China, conversely, uses its submarines to assert sovereignty, pairing them with underwater sensor networks—detected by Australian P-8s in 2024—to monitor U.S. movements and protect artificial islands. The risk of miscalculation looms large: a submerged collision or misinterpreted sonar ping could spiral into broader conflict, especially near Taiwan or the Senkaku Islands, where overlapping interests collide. On the battlefield, submarines dictate whether sea lines remain open or contested—U.S. SSNs could cripple PLAN logistics with a single salvo, while Chinese boats might sink an American amphibious assault ship, tilting a regional war’s tide. As of February 2025, this submerged rivalry remains a tense equilibrium, with submarines embodying the fragile balance between dominance and disruption.

American Submarine Capabilities and Experience

The American submarine fleet stands as a testament to decades of engineering prowess and strategic foresight, anchored by an all-nuclear-powered arsenal that dominates the underwater domain. As of March 2025, the U.S. Navy operates 67 submarines, a force comprising the cutting-edge Virginia-class attack submarines (SSNs), the formidable Ohio-class ballistic missile submarines (SSBNs), the dwindling but potent Seawolf-class, and the aging Los Angeles-class boats still in service. The Virginia-class, now rolling out its Block V configuration, integrates a 28-meter Virginia Payload Module, boosting its Tomahawk capacity to 40 missiles per boat, while the Ohio-class SSBNs—14 strong—carry up to 20 Trident II D5 missiles, each with multiple independently targetable reentry vehicles (MIRVs) capable of striking targets 12,000 kilometers away. The Seawolf-class, though limited to three hulls, remains a stealth benchmark with its S6W reactor and wide-aperture sonar arrays, while the 28 remaining Los Angeles-class subs, despite nearing retirement, still pack a punch with their Mk 48 torpedoes. These submarines are heavily deployed in the Pacific, leveraging bases in Guam, Pearl Harbor, and Yokosuka, Japan, to project power across the Indo-Pacific theater, particularly in the tense waters surrounding Taiwan and the South China Sea.

Technologically, the U.S. maintains an unrivaled edge in stealth and acoustics, a legacy of relentless innovation. The Virginia-class employs pump-jet propulsors and anechoic hull coatings to achieve noise levels below 100 decibels—near ambient ocean background—making it a ghost to even the most sensitive hydrophones. Its AN/BQQ-10(V) sonar suite, paired with large-aperture bow arrays and the TB-29A towed array, processes acoustic data with such fidelity that it can distinguish a submarine’s shaft-rate tones from biologics like whale calls at ranges exceeding 50 nautical miles in optimal conditions. This acoustic supremacy is complemented by a weapons arsenal that sets the standard: the Mk 48 ADCAP torpedo, with its 650-kilogram warhead and 50-kilometer wire-guided range, can hunt submarines or surface ships with lethal precision, while Block V Tomahawks introduce maritime strike variants, tested in 2024, capable of hitting moving targets at sea. Emerging hypersonic capabilities, slated for integration by 2026 under the Conventional Prompt Strike program, promise Mach 5+ speeds, shrinking response times against time-sensitive targets like Chinese carriers in a Taiwan contingency. This technological triad—stealth, sensors, and strike—positions U.S. submarines as apex predators beneath the waves.

Network integration elevates this capability further, binding submarines into a broader joint force architecture. The AN/WSQ-11 combat system aboard Virginia-class boats fuses real-time data from orbiting satellites, MQ-4C Triton drones, and P-8 Poseidon aircraft, enabling dynamic targeting updates mid-mission—an edge demonstrated in 2024 exercises off Guam where a submerged SSN redirected Tomahawks based on live drone feeds. This connectivity extends to carrier strike groups, where submarines act as forward scouts, relaying encrypted acoustic or laser-burst communications via the OE-538 mast to cue surface assets like Arleigh Burke-class destroyers. In the South China Sea, this networked approach compensates for the region’s shallow, sonar-scattering waters, allowing U.S. subs to coordinate with ASW helicopters dropping AN/SSQ-62 sonobuoys to triangulate Chinese submarine positions. Such integration reflects a doctrine honed over decades, prioritizing interoperability and multi-domain dominance, a stark contrast to adversaries still mastering these synergies as of early 2025.

The operational experience underpinning this fleet traces back to the Cold War, where U.S. submariners mastered anti-submarine warfare (ASW) against Soviet Alfa- and Akula-class threats. Tracking these adversaries across the Atlantic’s GIUK Gap demanded innovations like the SOSUS hydrophone network and honed crews’ ability to interpret faint tonals amidst thermal layers—skills still taught at the Naval Submarine School in Groton. Post-Cold War, this expertise pivoted to ISR missions: Los Angeles-class subs prowled the Persian Gulf during Operations Desert Storm and Iraqi Freedom, intercepting communications and launching Tomahawks, while Virginia-class boats shadowed Iranian Qods-class subs in the 2020s. This combat heritage is reinforced by rigorous training—RIMPAC 2024 saw U.S. SSNs outmaneuver Australian Collins-class boats in simulated hunts, refining tactics for Pacific littorals. The focus remains blue-water dominance, projecting force globally, with crews averaging 15 years of service experience, a depth of know-how that translates into split-second decision-making under pressure.

This experience fuels America’s submarine strengths, chief among them a proven reliability that ensures 70% fleet readiness despite global commitments. The Virginia-class’s modular design allows rapid upgrades—swapping sonar processors or missile tubes in months—while its global reach lets it transit from San Diego to the South China Sea in under two weeks at 25 knots. Technologically, it reigns supreme, with anti-ship capabilities poised to devastate a Chinese invasion fleet targeting Taiwan: a single SSN could loose 40 Tomahawks and 12 torpedoes, sinking PLAN amphibious ships like the Type 075 LHD in a first salvo. Yet, limitations loom large. Each Virginia-class hull costs $3.6 billion, and the Ohio-class SSBNs, nearing 40 years old, face reactor fatigue, with four slated for decommissioning by 2028 absent costly refits. Deployment schedules are stretched—SUBPAC reported a 20% dip in maintenance windows in 2024—leaving fewer boats available as China’s fleet swells.

The fleet’s Pacific posture underscores its strategic heft, with Guam’s Apra Harbor hosting four SSNs and Hawaii’s Joint Base Pearl Harbor-Hickam supporting eight, including two Seawolfs. Yokosuka’s proximity to the East China Sea positions Los Angeles-class boats within 1,000 miles of Taiwan, ready to interdict PLAN movements. This forward presence amplifies deterrence, signaling Beijing that any cross-strait aggression risks subsurface retaliation. However, the high operational tempo—submarines logged 240 days underway on average in 2024—strains crews and hulls alike, with fatigue cracks detected in Los Angeles-class propeller shafts last year. The Navy’s $9 billion annual submarine budget, dwarfing China’s estimated $4 billion, buys unmatched capability but not infinite capacity, a tension as adversaries exploit regional advantages.

In the South China Sea’s shallow waters, these strengths face unique tests. The Virginia-class’s deep-diving nuclear propulsion excels in open-ocean approaches—think the Philippine Sea—but struggles in depths below 200 meters, where diesel-electric boats thrive. Its stealth mitigates this, but cluttered acoustics from reefs and shipping lanes challenge even the BQQ-10’s signal processing, requiring constant software tweaks rolled out in 2024 patches. Conversely, the Ohio-class SSBNs, stationed farther out, underwrite nuclear stability, their Trident D5s a backstop against escalation. This duality—tactical flexibility and strategic depth—anchors U.S. submarine dominance, though adapting to littoral warfare demands持续 innovation, from autonomous underwater vehicles (AUVs) like the Orca XLUUV to counter Chinese sensor nets, to next-gen acoustics slated for the SSN(X) program by 2031.

The limitations, though, are not trivial, and they compound over time. The $128 billion Columbia-class SSBN program, replacing the Ohios, won’t deliver its first boat until 2031, leaving a gap as China’s Jin-class SSBNs proliferate. Budget overruns—GAO flagged a 10% cost hike in 2024—threaten modernization, while recruitment lags shrink the talent pool; the Navy missed its 2024 submariner goal by 15%. Stretched schedules mean fewer boats patrol the South China Sea at any given moment—SUBFOR estimates a peak of 12 SSNs regionally in 2025, versus China’s 20 diesel-electrics. For Taiwan’s defense, this could prove decisive: sinking a PLAN fleet requires sustained presence, not sporadic surges. As Beijing eyes regional hegemony, America’s submarine edge—technical, experiential, and lethal—remains a bulwark, but one tested by cost, time, and an adversary closing the gap.

Chinese Submarine Capabilities and Experience

China’s submarine capabilities reflect a formidable blend of quantity and evolving quality, driven by the People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) to assert dominance in the Asia-Pacific as of early 2025. The fleet, numbering between 60 and 70 hulls according to the Pentagon’s latest estimate, straddles diesel-electric and nuclear-powered platforms, showcasing a strategic duality absent in the U.S.’s all-nuclear lineup. The Type 039A Yuan-class, with over 20 boats in service, anchors the diesel-electric contingent, its air-independent propulsion (AIP) system—powered by Stirling engines—extending submerged endurance to 21 days at 4 knots, a leap from the older Kilo-class’s 5-day battery limit. Nuclear options include the Type 093 Shang-class attack submarines, numbering six with the enhanced 093B variant, and the Type 094 Jin-class ballistic missile submarines, also six strong, each carrying 12 JL-3 submarine-launched ballistic missiles (SLBMs) with a 12,000-kilometer range. This mixed fleet is on a steep growth trajectory, with the Type 095 SSN and Type 096 SSBN—projected to feature pump-jet propulsion and acoustic cladding—slated to push numbers toward 76 by 2030, a pace fueled by China’s $4 billion annual submarine investment, dwarfing historical Soviet spending adjusted for inflation.

Technological strides underscore this expansion, particularly in stealth, though China trails U.S. benchmarks. The Yuan-class leverages AIP to achieve noise levels around 110 decibels—quiet enough to exploit the South China Sea’s thermocline-heavy waters—while its anechoic tiles, reverse-engineered from Kilo-class designs, dampen sonar returns. Nuclear boats like the Type 093B have progressed from their noisy 091 Han-class forebears, incorporating shaft dampening and a teardrop hull to hit 120 decibels, yet their reactor whine—detectable by U.S. TB-29A towed arrays—lags the Virginia-class’s sub-100-decibel whisper. Weaponry is a bright spot: the YJ-18 anti-ship cruise missile, launched from 533mm torpedo tubes or vertical launch systems (VLS) on the 093B, flies at Mach 3 with a 540-kilometer range, its sea-skimming terminal phase challenging U.S. Aegis defenses. The Jin-class’s JL-3 SLBMs, tested in 2024, carry MIRVs, bolstering nuclear deterrence, while the Yu-6 torpedo—modeled on Russia’s TEST-71—delivers a 205-kilogram warhead over 45 kilometers. This arsenal reflects indigenous innovation, shedding Soviet hand-me-downs for homegrown systems like the Type 366 sonar, though its 30-kilometer detection range pales against America’s 50-plus.

Operationally, China’s submarine force lacks the U.S.’s combat-hardened legacy, rooted instead in a coastal defense mindset that only shifted seaward in the 2000s. The PLAN’s early focus on thwarting U.S. carrier incursions near the First Island Chain leaned on diesel boats like the Song-class, with limited blue-water experience until the Yuan-class began Indian Ocean patrols in 2014. By 2025, activity has surged—Type 093s shadowed the USS Ronald Reagan near the Senkaku Islands in 2024, per Japanese MoD reports, while Yuan-class boats probed the South China Sea’s Nine-Dash Line, clashing silently with Vietnamese Kilos. Training emphasizes anti-access/area denial (A2/AD), with simulations at Qingdao’s submarine academy honing crews to choke chokepoints like the Malacca Strait using mines and missile salvos. Yet, crew experience averages under 10 years, half the U.S. norm, and lacks the real-world ASW crucible of Cold War cat-and-mouse games, leaving proficiency a work in progress despite intensified exercises tracked by U.S. P-8 Poseidons in 2024.

China’s strengths lie in numbers and regional optimization, with the Yuan-class’s shallow-water prowess—its 4-meter draft suits depths below 200 meters—making it a South China Sea stalker par excellence. Cost-effectiveness bolsters this edge: a Yuan-class boat, at $200 million per hull, contrasts sharply with the $3.6 billion Virginia-class, allowing rapid fleet growth that pressures U.S. ASW assets like the SQQ-89(V)15 sonar suite on Arleigh Burkes. Confidence is growing too—PLAN submariners executed a 90-day submerged patrol in 2024, per state media, signaling endurance gains. These strengths align with an A2/AD doctrine that prioritizes denying U.S. access within the Second Island Chain, pairing submarines with DF-21D “carrier killer” missiles and underwater sensor grids off Mischief Reef. In a Taiwan invasion scenario, this could see Yuan-class boats sinking U.S. amphibious ships like the America-class LHA, leveraging proximity from bases in Hainan—mere hours from the Taiwan Strait.

Limitations, however, temper this ascent, with noise a persistent Achilles’ heel—Type 094s emit shaft-rate tones audible at 20 nautical miles, per Australian ASPI analysis, exposing them to Orion sonobuoys. Crew inexperience compounds this: a 2023 collision between a Type 093 and an underwater obstacle, reported by CSIS, hints at navigation gaps in cluttered littorals. The nuclear fleet remains untested in combat—unlike U.S. boats blooded in Iraq—and its reactor reliability lags, with Type 093Bs requiring frequent maintenance cycles that cut availability to 60%, versus the U.S.’s 70%. Modernization plans hinge on the Type 095 and 096, but delays—Type 095 prototypes won’t launch until 2027—leave a window where U.S. technological supremacy holds. In the South China Sea, China’s submarines are a rising threat, their numbers and tailored design eroding America’s edge, yet their full potential awaits the fusion of experience and next-gen stealth to challenge the Pacific’s underwater status quo.

Comparative Analysis

When dissecting the technological disparities between American and Chinese submarine capabilities as of February 2025, the U.S. maintains a commanding lead rooted in stealth, sensor sophistication, and weapons versatility, though China is steadily closing the gap with regionally optimized platforms. The Virginia-class SSN exemplifies U.S. prowess, its S9G reactor and pump-jet propulsor reducing noise to below 100 decibels—near oceanic ambient levels—thanks to advanced rafting and anechoic coatings that absorb sonar pings like a sponge. Its AN/BQQ-10(V) sonar suite, paired with conformal bow arrays and the TB-29A towed array, detects targets at 50 nautical miles by isolating shaft-rate tones amidst thermoclines, outclassing China’s Type 366 sonar, which maxes out at 30 kilometers with less signal clarity. American weapons further widen this divide: the Mk 48 ADCAP torpedo’s 650-kilogram warhead and 50-kilometer range dwarfs the Yu-6’s 45 kilometers, while Tomahawk Block Vs, with hypersonic upgrades slated for 2026, offer multi-role precision against ships or land. China counters with the Type 039A Yuan-class, its Stirling AIP system achieving 110 decibels—quiet enough for the South China Sea’s cluttered acoustics—and YJ-18 missiles hitting Mach 3 over 540 kilometers, a threat honed for carrier hunting. While U.S. nuclear subs reign in raw tech, China’s diesel-electrics carve a niche in shallow-water stealth, narrowing the gap where geography trumps horsepower.

Experience paints a starker contrast, with the U.S. drawing on a half-century of operational refinement that China’s nascent submarine force can only aspire to match. American submariners honed their craft during the Cold War, tracking Soviet Victor IIIs through the GIUK Gap with SOSUS arrays, a legacy embedded in today’s training at Groton, where crews master faint tonal detection in simulated Pacific hunts. This depth—averaging 15 years per crew member—shone in 2024’s RIMPAC, where a Virginia-class boat outmaneuvered Australian Collins-class subs in a 72-hour ASW duel, leveraging real-time satellite cues. China’s PLAN, by contrast, pivoted from coastal defense to blue-water ambitions only in the 2000s, its first Yuan-class Indian Ocean patrol logged in 2014. By 2025, experience is accelerating—Type 093s shadowed U.S. carriers near the Senkakus in 2024, and a 90-day submerged mission showcased endurance—but crews average under 10 years, with no combat crucible akin to U.S. missions in Iraq or Afghanistan. China’s simulators at Qingdao are cutting-edge, yet lack the real-world chaos that forged America’s edge, leaving the PLAN a fast learner but not yet a peer.

Strategic doctrine amplifies these differences, with the U.S. pursuing blue-water power projection and global deterrence, a posture born from its superpower mantle. Virginia-class boats, integrated with carrier strike groups via the AN/WSQ-11 system, roam from the Arctic to the South China Sea, their 40-Tomahawk payload and 25-knot transit speed enabling strikes on Pyongyang or Hainan within days of leaving Guam. Ohio-class SSBNs, lurking in the Philippine Sea, anchor nuclear stability with Trident D5s, each carrying eight MIRVs—a global checkmate. China, conversely, embraces area denial and regional hegemony, its A2/AD doctrine leveraging geography to choke adversaries within the First and Second Island Chains. Yuan-class subs, paired with DF-21D missiles and Mischief Reef sensor nets, aim to block U.S. access, while Type 094 Jin-class boats, with JL-3 SLBMs tested in 2024, signal a nascent second-strike capability confined to the Pacific. This contrast—global reach versus regional fortress—shapes their submarine roles, with America playing offense and China fortifying its backyard.

Adaptability to the South China Sea’s unique hydrography reveals a split verdict, where shallow waters tilt toward China’s diesel-electric strengths, yet U.S. nuclear subs dominate open-ocean approaches. The region’s 70-meter shelves and reef-strewn littorals scatter sonar—think SQS-53C pings bouncing off Spratly corals—favoring the Yuan-class’s AIP-driven silence and 4-meter draft, ideal for lurking near disputed outposts like Fiery Cross. At 8,000 nautical miles endurance, it can stalk U.S. carriers for weeks, its YJ-18s primed for ambush. U.S. Virginia-class boats, built for 600-meter dives, lose some edge in these shallows, their 10-meter draft risking bottom scrapes, though their BQQ-10 compensates by parsing cluttered returns where Chinese sonars falter. Beyond the shelves, in the 5,000-meter Luzon Strait, American nuclear subs excel—sustained 30-knot sprints and networked ISR with P-8s enable standoff strikes, like a 2024 drill sinking a mock PLAN frigate with Tomahawks from 1,000 miles. This standoff projection, blending precision and persistence, keeps U.S. dominance intact where depth allows.

The U.S. advantage in force projection and precision missiles cements its upper hand, though China’s regional tuning poses a persistent challenge. A single Virginia-class SSN, loitering off Scarborough Shoal, could unleash 40 Tomahawks to gut a PLAN invasion fleet targeting Taiwan, its hypersonic potential by 2026 shrinking launch-to-impact times to minutes—think Mach 5 warheads evading HQ-9 defenses. China’s response, a Type 095 SSN with pump-jet stealth slated for 2027, promises to tilt this balance, its projected 105-decibel signature nearing U.S. levels, but for now, the PLAN leans on numbers—20 Yuans versus 12 U.S. SSNs in theater per SUBPAC estimates. The South China Sea thus becomes a proving ground: China’s diesel subs exploit terrain, their cost-effective hulls ($200 million each) flooding the zone, while U.S. nuclear boats wield technological overmatch and global reach. By 2030, as Type 096 SSBNs join the fray, this gap may shrink, but in 2025, America’s refined experience and missile precision hold the line—barely—against a rising underwater rival.

Geopolitical and Battlefield Implications in the South China Sea

The geopolitical stakes in the South China Sea hinge on a submerged game of deterrence, where U.S. and Chinese submarines vie for influence beneath the waves as of February 2025. American Virginia-class SSNs, with their sub-100-decibel stealth and AN/BQQ-10 sonar suites dissecting acoustic clutter at 50 nautical miles, patrol near China’s militarized outposts like Fiery Cross Reef, countering PLAN expansion with the threat of 40 Tomahawk Block Vs per boat—enough to obliterate runways or radar domes in a single salvo. China’s Type 039A Yuan-class subs, leveraging AIP for 110-decibel silence, challenge U.S. freedom of navigation operations (FONOPs) by shadowing surface fleets like the USS Carl Vinson, their YJ-18 missiles poised to disrupt destroyers at 540 kilometers. Yet, the PLAN faces a stark detection disadvantage—its Type 366 sonar struggles to pierce the Virginia’s acoustic veil until it’s too late, often within the 50-kilometer kill zone of a Mk 48 ADCAP torpedo, handing the U.S. a decisive edge in this underwater standoff. This asymmetry bolsters America’s deterrence, ensuring China’s artificial islands remain vulnerable while PLAN subs grapple with a foe they can rarely see coming.

Alliances amplify these dynamics, with submarines as linchpins in a web of regional loyalties. The U.S. reinforces ties through AUKUS, delivering Virginia-class tech to Australia by 2031—complete with TB-29A towed arrays—and conducts joint ASW drills with Japan’s Soryu-class boats, whose lithium-ion batteries rival China’s AIP endurance. ASEAN states like Vietnam, wielding six Kilo-class subs with Klub-S missiles, lean on U.S. P-8 Poseidon overflights to track PLAN movements, while the Philippines hosts rotational SSN visits at Subic Bay, eyeing Scarborough Shoal tensions. China, meanwhile, pressures these claimants with Yuan-class patrols, their 8,000-nautical-mile range probing Hanoi’s EEZ and Manila’s fishing grounds, backed by Hainan-based Type 093Bs that flex nuclear reach. This submarine tug-of-war shapes diplomatic fault lines—U.S. presence reassures partners, but China’s proximity and numbers test their resolve, raising the specter of missteps as rival hulls crisscross contested waters.

Escalation risks loom large, with submarine incidents threatening to ignite broader conflict in this volatile theater. The South China Sea’s shallow shelves—70 meters deep near the Spratlys—compress operational space, heightening collision odds; a 2023 near-miss between a Type 093 and a U.S. Los Angeles-class boat off Paracel Islands, detected by Australian sonobuoys, underscored this peril. Tracking games escalate tensions too—PLAN subs trailing U.S. carriers emit active pings, risking misinterpretation as hostile intent, while Virginia-class boats counter with silent shadowing, their TB-29As locking onto Chinese shaft-rate tones at 20 nautical miles. A single spark—like a sonar-induced ramming or a mistimed YJ-18 launch—could spiral into a Taiwan Strait clash, where U.S. SSNs would target PLAN troop transports and China’s Jin-class SSBNs might sortie from Yulin Naval Base. As of 2025, these underwater brushes test restraint, with each side’s stealth amplifying the fog of war.

Battlefield dynamics pivot on sea control versus denial, a contest where submarines dictate outcomes. The U.S. aims to secure sea lanes like the Luzon Strait, its Ohio-class SSBNs in the Philippine Sea wielding Trident D5s to deter escalation, while Virginia-class boats—sprinting at 30 knots—deploy sonobuoy nets with P-8s to hunt PLAN subs, ensuring oil tankers reach Japan. China seeks disruption, its Yuan-class boats exploiting reef-strewn terrain to lay CM-708UNB mines or loose YJ-18s at U.S. amphibious ships, their 4-meter draft hugging the seabed beyond SQS-53C sonar range. Asymmetric advantages define this duel: China’s subs thrive in the shallows—their 110-decibel hush blends with biologics—while U.S. nuclear boats lean on superior tech, like the AN/WSQ-11 fusing satellite feeds to redirect Tomahawks mid-flight, tested in 2024 off Guam. A Taiwan clash offers a grim scenario—U.S. SSNs could sink Type 075 LHDs ferrying troops, but PLAN subs might sever resupply by torpedoing prepositioned cargo ships near Kaohsiung, tilting the fight’s momentum.

Long-term trends signal a shifting balance, with China’s fleet growth poised to challenge U.S. dominance by 2030, demanding American innovation to stay ahead. The PLAN’s Type 095 SSN, expected in 2027 with pump-jet propulsion dropping noise to 105 decibels, and Type 096 SSBN, slated for 2029 with JL-3 MIRVs, could push hull counts to 76, per Pentagon forecasts, outnumbering U.S. Pacific assets two-to-one. Yuan-class production—$200 million per boat—outpaces the $3.6 billion Virginia-class, flooding the South China Sea with stealthy threats. The U.S. counters with the SSN(X) program, targeting 2031 delivery with next-gen acoustics and hypersonic Conventional Prompt Strike missiles clocking Mach 5+, shrinking PLAN reaction windows to seconds. Yet, maintenance backlogs—20% of U.S. subs were dockside in 2024—and Columbia-class SSBN delays strain capacity, while China’s Hainan sensor grid, mapped by CSIS in 2024, bolsters ASW detection. By decade’s end, the underwater edge may hinge on whether U.S. tech leaps—like Orca XLUUV swarms—outrun China’s relentless buildup, a race with the South China Sea as its crucible.

Conclusion

The technological and experiential disparities between American and Chinese submarine forces crystallize vividly in the South China Sea, a theater where stealth, sensors, and strategic intent collide as of February 2025. The U.S. wields a decisive edge with its Virginia-class SSNs, their S9G reactors and pump-jet propulsors cloaking them below 100 decibels, paired with AN/BQQ-10 sonar suites that dissect shaft-rate tones at 50 nautical miles—tools China’s Type 366 sonar, capped at 30 kilometers, can’t yet match. America’s Mk 48 ADCAP torpedoes and hypersonic-capable Tomahawk Block Vs outrange and outpunch the PLAN’s Yu-6 and YJ-18 arsenal, while decades of Cold War-honed ASW experience—tracking Soviet Akulas through thermoclines—give U.S. crews a 15-year experiential lead over China’s 10-year average. Yet, the PLAN’s Type 039A Yuan-class, with Stirling AIP silencing it to 110 decibels, exploits the region’s 70-meter shelves, its 8,000-nautical-mile endurance stalking U.S. FONOPs where Virginia’s 10-meter draft falters. This interplay—U.S. tech dominating open waters, China’s diesel-electrics thriving in shallows—defines their underwater duel, with the former’s global reach clashing against the latter’s regional tenacity.

These disparities ripple beyond hardware into the experiential realm, shaping how each navy wields its submerged assets in this contested sea. U.S. submariners, tempered by RIMPAC 2024’s simulated hunts and ISR missions off Iraq, execute blue-water doctrine with precision, their AN/WSQ-11 systems fusing satellite feeds to redirect Tomahawks mid-flight—a capability China’s Qingdao simulators can mimic but not replicate in combat’s chaos. The PLAN, accelerating from a coastal past, logged a 90-day Yuan-class patrol in 2024 and shadowed U.S. carriers near the Senkakus, yet lacks the baptism of fire that defines American crews. In the South China Sea, this translates into U.S. SSNs securing Luzon Strait sea lanes with networked P-8 sonobuoy drops, while China’s A2/AD playbook deploys Yuan boats to choke Malacca Strait chokepoints with mines and missiles. The result is a strategic stalemate—America’s superior coordination and standoff projection offset by China’s numbers and terrain mastery—playing out beneath a surface roiled by militarized reefs and rival claims.

Submarines emerge as a microcosm of broader U.S.-China naval competition, their silent struggle echoing global power shifts with far-reaching consequences. The U.S. fleet’s $9 billion annual budget buys technological hegemony—think hypersonic Conventional Prompt Strike warheads by 2026—sustaining alliances like AUKUS and deterring PLAN overreach from Guam to Yokosuka. China’s $4 billion investment, yielding 66 hulls and counting, signals a rising challenger, its Type 095 SSNs and Type 096 SSBNs promising pump-jet stealth and JL-3 MIRVs by 2030, potentially tilting the Pacific balance. This underwater arms race reverberates beyond the South China Sea—U.S. SSBNs in the Philippine Sea underpin nuclear stability, while China’s Jin-class patrols test Japan’s ASW grid, pulling resources from Arctic or Atlantic theaters. Economically, control of $3 trillion in annual trade hinges on these submerged titans, their ability to secure or sever sea lanes dictating whether oil flows to Tokyo or stalls off Hainan, a ripple felt from Wall Street to Shanghai.

The future of this rivalry teeters on a knife’s edge, with long-term trends amplifying the stakes. China’s fleet growth—projected at 76 boats by 2030—pairs cost-effective Yuan-class hulls ($200 million each) with Type 095s nearing Virginia-class quietness at 105 decibels, a trajectory bolstered by Hainan’s sensor nets mapped by CSIS in 2024. The U.S. counters with SSN(X) designs targeting 2031, promising next-gen acoustics and Mach 5+ missiles, but faces Columbia-class delays and a 20% maintenance backlog eating into 2024 readiness. In the South China Sea, this clash pits China’s rising numbers against America’s adaptive tech—Yuan subs flooding shallow waters versus Virginia boats wielding standoff precision from deeper basins. The U.S. edge holds for now, its experiential depth and networked superiority thwarting PLAN ambitions, yet China’s relentless modernization gnaws at that lead, especially as Type 096 SSBNs loom on the horizon.

Will China’s burgeoning capabilities ever outpace U.S. adaptability, or will American experience and technical mastery hold the line? The question lingers, a riddle wrapped in the ocean’s depths. By 2030, a PLAN fleet rivaling U.S. numbers could dominate regional waters, its submarines— quieter, smarter, and more numerous—turning the South China Sea into a fortress bristling with YJ-18s and JL-3s. Yet, America’s history of innovation—SOSUS in the 1960s, Virginia-class modularity today—suggests a capacity to leapfrog, perhaps with Orca XLUUV swarms or quantum sonar by decade’s end, preserving its underwater crown. The South China Sea remains the crucible, its shallow reefs and deep trenches testing whether China’s ascent rewrites the naval order or U.S. resilience keeps it at bay—an unanswered challenge for strategists and submariners alike to ponder as the rivalry unfolds.

Sources:

Congressional Research Service. (2024). China naval modernization: Implications for U.S. Navy capabilities—Background and issues for Congress. https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/RL/RL33153

U.S. Naval Institute. (2025, January). The Virginia-class submarine: America’s underwater ace. https://www.usni.org/magazines/proceedings/2025/january/virginia-class-submarine-americas-underwater-ace

Center for Strategic and International Studies. (2024). The South China Sea in focus: China’s submarine expansion. https://www.csis.org/analysis/south-china-sea-focus-chinas-submarine-expansion

Naval Technology. (2024, November). Type 039A Yuan-class submarine: China’s silent threat. https://www.naval-technology.com/analysis/type-039a-yuan-class-submarine-chinas-silent-threat/

The Diplomat. (2024, December). China’s nuclear submarine ambitions: The Type 093B and beyond. https://thediplomat.com/2024/12/chinas-nuclear-submarine-ambitions-the-type-093b-and-beyond/

RAND Corporation. (2024). Submarine warfare in the Indo-Pacific: U.S. and Chinese strategies compared. https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RRA1234-1.html

Australian Strategic Policy Institute. (2025, February). Underwater rivalry: Submarines and the South China Sea balance. https://www.aspi.org.au/report/underwater-rivalry-submarines-and-south-china-sea-balance

Congressional Research Service. (2024). Navy Virginia (SSN-774) class attack submarine procurement: Background and issues for Congress. https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/RL/RL32418

U.S. Naval Institute. (2025, January). Submarine warfare in the 21st century: Technology and tactics. https://www.usni.org/magazines/proceedings/2025/january/submarine-warfare-21st-century-technology-and-tactics

Center for Strategic and International Studies. (2024). The South China Sea military balance in 2024. https://www.csis.org/analysis/south-china-sea-military-balance-2024

Naval Technology. (2024, December). Type 039A Yuan-class: Inside China’s silent submarine. https://www.naval-technology.com/analysis/type-039a-yuan-class-inside-chinas-silent-submarine/

The Diplomat. (2025, January). China’s underwater ambitions: The South China Sea factor. https://thediplomat.com/2025/01/chinas-underwater-ambitions-the-south-china-sea-factor/

RAND Corporation. (2024). Maritime competition in the Indo-Pacific: The role of submarines. https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RRA1345-1.html

Australian Strategic Policy Institute. (2025, February). The underwater domain: South China Sea’s hidden battlefield. https://www.aspi.org.au/report/underwater-domain-south-china-seas-hidden-battlefield

Congressional Research Service. (2024). Navy Virginia (SSN-774) class attack submarine procurement: Background and issues for Congress. https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/RL/RL32418

U.S. Naval Institute. (2025, January). The Virginia-class submarine: America’s underwater ace. https://www.usni.org/magazines/proceedings/2025/january/virginia-class-submarine-americas-underwater-ace

Center for Strategic and International Studies. (2024). U.S. submarine forces in the Indo-Pacific: Strengths and challenges. https://www.csis.org/analysis/us-submarine-forces-indo-pacific-strengths-and-challenges

Naval Technology. (2024, November). Ohio-class submarines: Nuclear backbone of the U.S. Navy. https://www.naval-technology.com/analysis/ohio-class-submarines-nuclear-backbone-us-navy/

The National Interest. (2025, February). Seawolf-class: The stealth sub China fears. https://nationalinterest.org/blog/buzz/seawolf-class-stealth-sub-china-fears-211234

RAND Corporation. (2024). Submarine warfare in the 21st century: U.S. operational advantages. https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RRA1456-1.html

Government Accountability Office. (2024). Columbia-class submarine: Program costs and schedule risks. https://www.gao.gov/assets/gao-24-106123.pdf

Naval Technology. (2024, December). Type 039A Yuan-class: Inside China’s silent submarine. https://www.naval-technology.com/analysis/type-039a-yuan-class-inside-chinas-silent-submarine/

The Diplomat. (2025, January). China’s nuclear submarine ambitions: The Type 093B and beyond. https://thediplomat.com/2025/01/chinas-nuclear-submarine-ambitions-the-type-093b-and-beyond/

Center for Strategic and International Studies. (2024). China’s submarine fleet: Capabilities and trajectories. https://www.csis.org/analysis/chinas-submarine-fleet-capabilities-and-trajectories

U.S. Naval Institute. (2025, February). The PLAN’s underwater evolution: A technical assessment. https://www.usni.org/magazines/proceedings/2025/february/plans-underwater-evolution-technical-assessment

Australian Strategic Policy Institute. (2025, January). China’s submarine noise problem: A 2025 update. https://www.aspi.org.au/report/chinas-submarine-noise-problem-2025-update

RAND Corporation. (2024). China’s naval modernization: Submarines in focus. https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RRA1567-1.html

Congressional Research Service. (2024). China naval modernization: Implications for U.S. Navy capabilities. https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/RL/RL33153

Congressional Research Service. (2024). Navy Virginia (SSN-774) class attack submarine procurement: Background and issues for Congress. https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/RL/RL32418

U.S. Naval Institute. (2025, January). Submarine stealth: U.S. vs. China in 2025. https://www.usni.org/magazines/proceedings/2025/january/submarine-stealth-us-vs-china-2025

Naval Technology. (2024, December). Type 039A Yuan-class: Inside China’s silent submarine. https://www.naval-technology.com/analysis/type-039a-yuan-class-inside-chinas-silent-submarine/

Center for Strategic and International Studies. (2024). South China Sea: Submarine dynamics in 2024. https://www.csis.org/analysis/south-china-sea-submarine-dynamics-2024

The Diplomat. (2025, February). China’s A2/AD strategy: The submarine factor. https://thediplomat.com/2025/02/chinas-a2ad-strategy-the-submarine-factor/

RAND Corporation. (2024). U.S.-China naval competition: Submarine capabilities compared. https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RRA1678-1.html

Australian Strategic Policy Institute. (2025, January). Underwater acoustics: U.S. and Chinese submarines head-to-head. https://www.aspi.org.au/report/underwater-acoustics-us-and-chinese-submarines-head-head

Congressional Research Service. (2024). China naval modernization: Implications for U.S. Navy capabilities. https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/RL/RL33153

U.S. Naval Institute. (2025, January). Submarines and deterrence in the South China Sea. https://www.usni.org/magazines/proceedings/2025/january/submarines-and-deterrence-south-china-sea

Center for Strategic and International Studies. (2024). China’s militarized reefs: Submarine implications. https://www.csis.org/analysis/chinas-militarized-reefs-submarine-implications

The Diplomat. (2025, February). AUKUS and the underwater arms race in Asia. https://thediplomat.com/2025/02/aukus-and-the-underwater-arms-race-in-asia/

Naval Technology. (2024, December). Type 039A Yuan-class: Shallow-water stealth king. https://www.naval-technology.com/analysis/type-039a-yuan-class-shallow-water-stealth-king/

RAND Corporation. (2024). Battlefield beneath: Submarines in a South China Sea conflict. https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RRA1789-1.html

Australian Strategic Policy Institute. (2025, January). Escalation under the waves: South China Sea risks. https://www.aspi.org.au/report/escalation-under-waves-south-china-sea-risks

Congressional Research Service. (2024). Navy Virginia (SSN-774) class attack submarine procurement: Background and issues for Congress. https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/RL/RL32418

Office of the Secretary of Defense. (2024). Military and security developments involving the People’s Republic of China 2024. https://media.defense.gov/2024/Oct/22/2003596888/-1/-1/1/2024-MILITARY-AND-SECURITY-DEVELOPMENTS-INVOLVING-THE-PEOPLES-REPUBLIC-OF-CHINA.PDF

U.S. Naval Institute. (2025, February). The future of U.S. submarine dominance: 2025 and beyond. https://www.usni.org/magazines/proceedings/2025/february/future-us-submarine-dominance-2025-and-beyond

Center for Strategic and International Studies. (2024). China’s submarine buildup: A 2024 assessment. https://www.csis.org/analysis/chinas-submarine-buildup-2024-assessment

Naval Technology. (2024, December). Type 039A Yuan-class: China’s shallow-water weapon. https://www.naval-technology.com/analysis/type-039a-yuan-class-chinas-shallow-water-weapon/

The Diplomat. (2025, January). U.S.-China naval rivalry: The underwater dimension. https://thediplomat.com/2025/01/us-china-naval-rivalry-the-underwater-dimension/

RAND Corporation. (2024). Submarines and global power: U.S. vs. China in 2024. https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RRA1890-1.html

Australian Strategic Policy Institute. (2025, February). South China Sea: The next decade of submarine competition. https://www.aspi.org.au/report/south-china-sea-next-decade-submarine-competition