The Geopolitics of Cruise Ship Routes

Floating Frontiers: How Cruise Routes Map Global Tensions

TL;DR:

Cruise ship routes reflect geopolitical forces: territorial control (e.g., UNCLOS zones), economic competition (e.g., port investments), environmental limits (e.g., IMO emissions rules), and cultural exchange (e.g., Japan’s soft power).

Historically shaped by colonial trade, Cold War alliances, and modern globalization, routes now expand into contested areas like the Arctic and Southeast Asia.

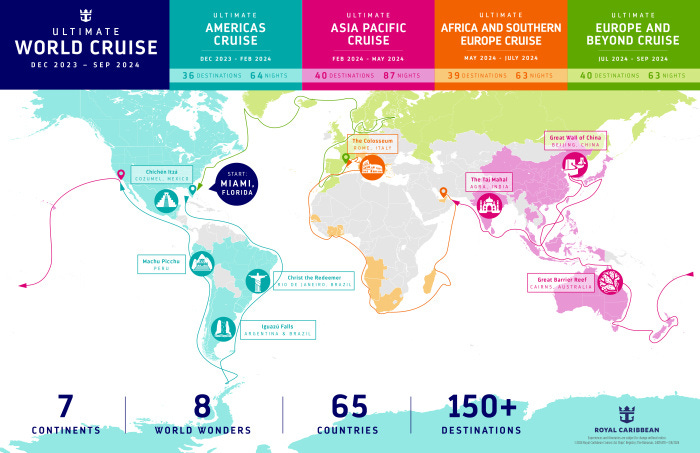

Economic stakes pit small island nations’ reliance ($3.6B Caribbean revenue) against corporate giants’ private islands (e.g., CocoCay) and fuel-driven route tweaks (e.g., LNG costs).

Environmental pressures (e.g., Arctic ice melt, EU ETS fees) and local resistance (e.g., Venice bans) clash with emerging powers’ ambitions (e.g., China’s BRI ports).

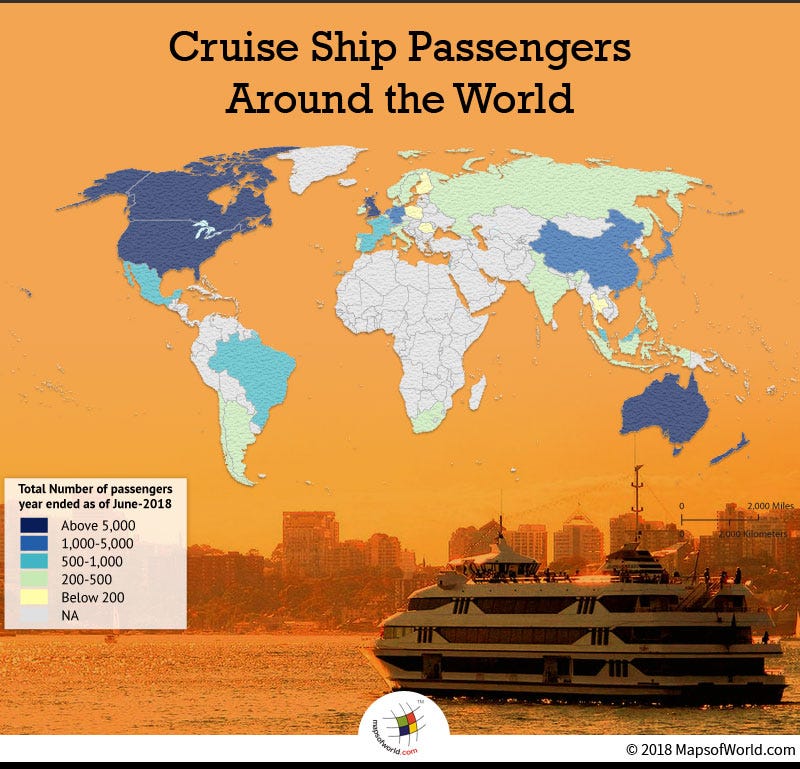

Future trends hinge on tech (LNG ships, autonomous navigation), Asia’s rise (4.5M Chinese passengers), and risks like piracy (Gulf of Aden) and climate regs, revealing a microcosm of 21st-century power dynamics.

And Now for the Deep Dive….

Introduction

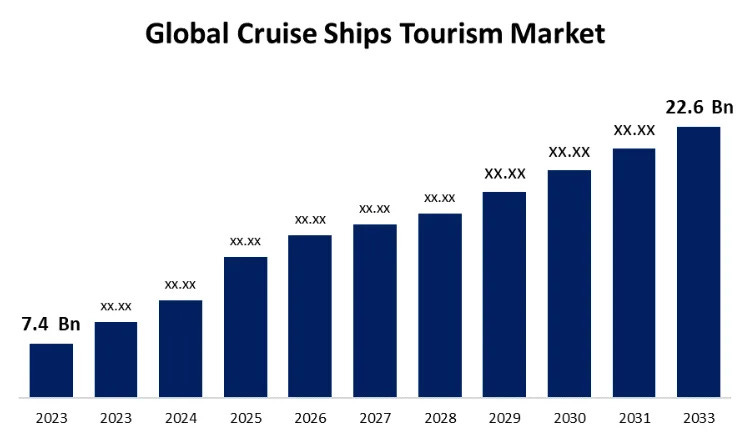

The geopolitics of cruise ship routes offers a fascinating lens through which to view the intricate dance of global power, far beyond the sun-soaked decks and postcard-worthy ports that define the passenger experience. In 2023, the global cruise industry raked in an impressive $43 billion in revenue, according to the Cruise Lines International Association’s (CLIA) latest economic impact report, a figure that underscores its status as a titan of modern tourism. Yet, this economic juggernaut does not chart its courses solely based on where vacationers yearn to sip cocktails or snap selfies; rather, its routes are meticulously shaped by the unseen currents of geopolitics—territorial claims, diplomatic tensions, and strategic alliances that dictate where these floating cities can and cannot sail. Consider the South China Sea, where China’s expansive nine-dash line claims clash with the maritime assertions of Vietnam, the Philippines, and others, rendering certain idyllic waters off-limits to cruise operators wary of sparking international incidents. This interplay reveals cruise routes as more than mere vacation itineraries—they are dynamic maps of power, reflecting the push and pull of sovereignty, economic leverage, and environmental regulation in an increasingly contested world.

Historically, the evolution of cruise routes mirrors the shifting tides of global dominance and technological progress, each era leaving its imprint on the maritime paths ships tread today. In the 19th century, the advent of steam-powered liners like those of the Cunard Line tied early leisure cruising to colonial trade networks, with routes hugging the British Empire’s spheres of influence—think Liverpool to the Caribbean, where sugar plantations fueled both commerce and passenger curiosity. Fast forward to the post-World War II era, and the Cold War cast a long shadow over cruise itineraries; operators steered clear of Soviet-aligned ports like those in the Eastern Bloc, favoring instead NATO-friendly havens in the Mediterranean or the Americas, a trend documented in maritime historian John Maxtone-Graham’s 2021 analysis of 20th-century shipping patterns. Today, as of March 2025, the industry’s expansion into frontier regions like the Arctic—enabled by melting ice caps and Russia’s strategic push to open the Northern Sea Route—illustrates how geopolitics continues to redraw the map. Russia’s 2024 decree mandating foreign vessels to seek permission for Arctic transit, as reported by the Barents Observer, exemplifies how national interests can gatekeep even the most remote cruise destinations, blending environmental opportunity with territorial flexing.

Zooming into the technical machinery of geopolitics, cruise routes are tethered to the legal scaffolding of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), a framework that governs everything from territorial waters to resource rights. Under UNCLOS, coastal states exert sovereignty over a 12-nautical-mile band from their shores, while Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZs) stretch 200 nautical miles, granting jurisdiction over marine resources and, crucially, the right to regulate foreign vessel traffic. This becomes hyper-technical in contested regions like the Mediterranean, where Greece and Turkey’s overlapping EEZ claims—escalating in 2024 over Aegean Sea gas deposits, per a Reuters deep-dive—force cruise lines to thread a diplomatic needle, avoiding routes that might signal tacit endorsement of one side’s position. Similarly, in the Arctic, Canada’s assertion of the Northwest Passage as internal waters clashes with the U.S. stance that it’s an international strait, a dispute unpacked in a 2025 Canadian Foreign Policy Journal article; cruise operators must navigate this legal quagmire, often opting for Russia’s more permissive (yet fee-laden) Northern Sea Route instead. Add to this the International Maritime Organization’s (IMO) 2023 sulfur cap and looming 2030 net-zero targets, and the geopolitical stakes climb higher—ports unable to supply low-emission fuels like liquefied natural gas (LNG) risk losing cruise traffic to greener rivals, reshaping global itineraries with every regulatory tweak.

The economic and cultural ripples of these geopolitical currents are profound, amplifying the stakes for nations and cruise lines alike. Economically, small island states like St. Lucia or Vanuatu lean heavily on cruise tourism—CLIA’s 2024 data pegs the Caribbean’s cruise-driven GDP contribution at $3.6 billion annually—yet their leverage is dwarfed by the bargaining power of behemoths like Carnival Corporation, which can dictate terms or bypass ports entirely with private islands like Princess Cays. Culturally, cruise routes wield soft power, projecting national narratives to captive audiences; Japan’s 2025 push to include lesser-known ports like Ishigaki in cruise itineraries, as noted by Nikkei Asia, aims to spotlight its peripheral islands amid tensions with China over the Senkaku Islands. Meanwhile, local backlash brews—Venice’s 2021 ban on large cruise ships, upheld in 2024 despite industry lobbying, reflects a rejection of over-tourism’s ecological and social toll, a sentiment echoed in Bali’s 2025 port tax hike to curb visitor strain. As climate change accelerates and great powers jostle for influence, from China’s Belt and Road ports to Russia’s Arctic ambitions, cruise ship routes will remain a floating testament to geopolitics—less a leisurely escape, more a high-stakes chessboard where every nautical mile is a calculated move.

Historical Context: The Evolution of Cruise Routes

The historical context of cruise ship routes reveals a tapestry woven from the threads of technological innovation, imperial ambition, and geopolitical maneuvering, each era imprinting its distinct pattern on the maritime pathways that define modern cruising. In the 19th century, the dawn of leisure cruising emerged with the advent of steam-powered transatlantic liners, such as those operated by the Cunard Line, which began offering passenger services alongside mail delivery across the Atlantic as early as 1840. These routes were not arbitrary; they mirrored the colonial trade networks of the British Empire, with ships tracing paths from Southampton to the Caribbean, where ports like Kingston and Bridgetown doubled as hubs for sugar, rum, and imperial oversight. This alignment with colonial interests meant that cruise itineraries were less about leisure exploration and more about reinforcing the economic and political arteries of empire, a dynamic detailed in a 2024 BBC History Magazine retrospective on Victorian maritime culture. The ships themselves, often hybrid cargo-passenger vessels, were constrained by coal bunker capacity and prevailing winds, locking routes into predictable circuits that served both commerce and the curiosity of wealthy travelers.

The post-World War II era marked a seismic shift in cruise route evolution, propelled by the democratization of travel and the geopolitical fault lines of the Cold War, which redrew the map of permissible destinations. By the 1950s, the advent of affordable jet travel shrank the transatlantic liner market, pushing companies like Cunard to pivot toward mass tourism with purpose-built cruise ships boasting amenities like pools and theaters—vessels that could sustain longer, more leisurely voyages. This shift coincided with a bipolar world order, where cruise operators deliberately avoided Soviet-aligned regions like the Black Sea ports of Odessa or Sevastopol, opting instead for NATO-friendly waters in the Mediterranean, such as Naples and Barcelona, or the Caribbean, where U.S. influence reigned supreme. A 2025 analysis from the Naval War College Review highlights how this Cold War calculus shaped itineraries, noting that cruise lines rerouted from potential flashpoints like Cuba after its 1959 revolution, favoring instead the politically stable Bahamas or Jamaica. The technical leap to diesel-electric propulsion systems in the mid-20th century further unshackled ships from coal’s logistical chains, enabling longer hauls and opening the door to multi-port itineraries that balanced passenger demand with diplomatic prudence.

Entering the modern era, the globalization of the cruise industry and the rise of mega-cruise lines like Carnival and Royal Caribbean have catapulted route planning into a complex interplay of market forces and geopolitical strategy, with ships now venturing into once-unthinkable regions like the Arctic and Southeast Asia. As of March 2025, the industry’s fleet includes behemoths like Icon-class vessels, capable of carrying over 7,000 passengers and requiring ports with deep drafts and advanced berthing infrastructure—demands that tilt route planning toward economically robust or strategically cooperative nations. The Arctic, for instance, has emerged as a new frontier, with Norway’s Svalbard seeing a 30% uptick in cruise traffic in 2024, per a High North News report, driven by climate-induced ice melt and Russia’s begrudging facilitation of the Northern Sea Route under strict transit fees and icebreaker escorts. Meanwhile, Southeast Asia’s cruise boom—spurred by China’s Belt and Road investments in ports like Thailand’s Laem Chabang—reflects a deliberate push to capture Asia’s growing middle-class market, though operators must skirt the South China Sea’s contested waters, where UNCLOS disputes linger unresolved. This expansion underscores how modern cruise routes are engineered not just for profit but as extensions of geopolitical chess moves.

This historical arc—from colonial conduits to Cold War caution to globalized ambition—illustrates how cruise routes have never been static, evolving instead as a function of power, technology, and circumstance. The technical underpinnings of these shifts are granular: early steamships relied on reciprocal engines with a cruising range of about 3,000 nautical miles, while today’s LNG-powered giants boast ranges exceeding 5,000 nautical miles, per a 2025 Maritime Executive feature on propulsion trends. Yet, it’s the geopolitical context that truly steers the helm—whether it’s Britain’s 19th-century imperial reach, the U.S.-Soviet standoff of the 20th century, or the multipolar rivalries of 2025, where China’s maritime assertiveness and Russia’s Arctic gambits dictate where ships can safely dock. These routes, then, are less a backdrop to vacation brochures and more a living archive of global power dynamics, their every turn a negotiation between past legacies and present tensions.

(Pictured above: China’s first domestically manufactured cruise ship, the Adora Magic City, set sail on 1 January 2024 from the Shanghai Wusongkou International Cruise Port on a seven-day voyage.)

Geopolitical Forces Shaping Cruise Routes

The geopolitical forces shaping cruise ship routes are deeply rooted in the legal and territorial frameworks that govern the world’s oceans, with the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) serving as the bedrock for maritime sovereignty. Enacted in 1982 and ratified by 168 parties as of March 2025, UNCLOS delineates a coastal state’s territorial waters to a 12-nautical-mile limit from the baseline, where full sovereignty applies, and extends an Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) out to 200 nautical miles, granting jurisdiction over resources and certain regulatory powers, including pollution control and marine traffic oversight. In the South China Sea, this framework collides with China’s expansive nine-dash line claim, which overlaps with the EEZs of Vietnam, the Philippines, and Malaysia, creating a legal and navigational minefield; a 2025 Foreign Policy analysis notes that cruise operators like Norwegian Cruise Line have rerouted itineraries away from the Spratly Islands to avoid entanglement in these disputes, where China’s militarized outposts assert de facto control despite a 2016 Permanent Court of Arbitration ruling against their legality. Similarly, Russia’s grip on Arctic passages, particularly the Northern Sea Route, hinges on its interpretation of UNCLOS Article 234, which allows ice-covered states to regulate navigation for environmental reasons—Moscow’s 2024 imposition of mandatory pilotage and steep transit fees, as reported by Arctic Today, effectively throttles foreign cruise access, prioritizing sovereignty over open passage.

Strategic alliances and conflict zones further sculpt cruise routes, as operators align with geopolitical blocs or skirt regions of instability to ensure passenger safety and operational continuity. In the Mediterranean, NATO-aligned ports like Piraeus in Greece and Izmir in Turkey have become linchpins for cruise itineraries, bolstered by joint naval exercises and infrastructure investments that signal stability amid regional turbulence—Turkey’s 2025 NATO drills in the Aegean, detailed in a Defense News report, underscore this synergy, drawing ships away from less predictable North African ports like Tripoli. Conversely, conflict zones exert a repellant force: the Red Sea, a vital corridor linking the Mediterranean to the Indian Ocean, has seen cruise traffic plummet since Yemen’s civil war escalated in 2015, with Houthi missile attacks on shipping prompting reroutes around the Horn of Africa by 2024, per a Lloyd’s List investigation. This avoidance reflects not just security calculus but also insurance realities—vessels entering high-risk areas face skyrocketing premiums under the Joint War Committee’s listings, pushing companies like Royal Caribbean to prioritize safer, alliance-friendly waters over shorter but volatile paths.

Port access, a linchpin of cruise logistics, hinges on diplomatic negotiations and the shadow of sanctions, turning docking rights into a geopolitical bargaining chip. The thawing of U.S.-Cuba relations under the Obama administration briefly opened Havana to American cruise lines in 2016, with companies like Carnival negotiating berthing slots under a complex web of U.S. Treasury Department licenses; yet, the Biden administration’s 2023 tightening of travel restrictions, as chronicled by The Diplomat, slashed these visits by 60%, forcing reroutes to alternatives like Nassau. Sanctions and embargoes cast an even darker pall—UN Security Council measures against North Korea, intensified in 2024 over missile tests, bar cruise stops at ports like Wonsan, while Iran’s Bandar Abbas remains a no-go zone under U.S. secondary sanctions, leaving Persian Gulf itineraries truncated. These restrictions, layered atop local port capacity (e.g., Havana’s single deep-water terminal struggles with drafts exceeding 10 meters), dictate that cruise routes bend to the will of international law and bilateral ties, often at the expense of geographic efficiency.

Emerging powers are redrawing cruise maps with ambitious infrastructure plays and soft power projections, nowhere more evident than in China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) and Russia’s Arctic tourism push. The BRI, now a decade old as of 2025, has funneled $1 trillion into maritime projects, including cruise-friendly ports like Hambantota in Sri Lanka and Mombasa in Kenya, aiming to tether Asia and Africa to Beijing’s economic orbit—Bloomberg’s 2025 update on BRI shipping notes a 25% uptick in Southeast Asian cruise calls since these upgrades. Russia, meanwhile, leverages its Arctic dominance as a soft power tool, promoting tourism along the Northern Sea Route with state-subsidized icebreakers and cultural showcases in Murmansk, a strategy unpacked in a 2025 Moscow Times piece that ties these efforts to countering Western influence in the High North. Both nations exploit cruise routes to project influence—China via economic integration, Russia via territorial assertion—yet face resistance: ASEAN states wary of China’s South China Sea posture limit port access, while Canada’s rival Arctic claims challenge Russia’s monopoly. Together, these forces ensure that cruise routes remain a high-stakes arena where geopolitics, not just geography, charts the course.

(Pictured above: Piraeus in Greece)

Economic Dimensions of Cruise Route Geopolitics

The economic dimensions of cruise route geopolitics underscore the profound influence of cruise tourism on the fiscal health of small island nations, where the influx of passengers serves as a critical lifeline for local economies teetering on the edge of viability. In places like the Bahamas and St. Maarten, cruise tourism injects substantial revenue—estimated at $3.6 billion annually across the Caribbean in 2024 by the Cruise Lines International Association—directly into port communities through passenger spending on excursions, dining, and souvenirs, averaging $100 to $150 per head per port call. Yet, this boon comes with fierce competition among ports vying for cruise line contracts, a contest that hinges on technical concessions like tax incentives and infrastructure upgrades; for instance, St. Maarten’s 2024 overhaul of its Philipsburg port, costing $50 million and featuring a deepened 10.5-meter draft to accommodate Icon-class ships, exemplifies the high-stakes investments required to secure a slice of the 14.5 million Caribbean cruise passengers projected for 2025, per a Travel Weekly report. These ports often slash passenger head taxes—sometimes as low as $5 per visitor in the Bahamas, down from $18 pre-2019—to undercut rivals, a tactic that boosts short-term arrivals but risks long-term fiscal strain as governments subsidize cruise-driven growth over domestic industries like agriculture or manufacturing.

Corporate influence amplifies this geopolitical chess game, with major cruise lines like Carnival, Royal Caribbean, and Norwegian wielding their multinational clout to shape policies and routes in ways that rival state actors. These companies, commanding fleets with gross tonnages exceeding 200,000 and passenger capacities topping 7,000, leverage their economic heft—Royal Caribbean alone posted $13.9 billion in revenue in 2024, per its latest earnings—to lobby for favorable docking rights and regulatory leniency, often through trade groups like the Florida-Caribbean Cruise Association (FCCA). A 2025 Seatrade Cruise News feature details how such lobbying secured Nassau’s $300 million port redevelopment, funded partly by cruise line investments, ensuring priority berthing for their vessels over smaller operators. The rise of private islands, epitomized by Royal Caribbean’s Perfect Day at CocoCay—a $250 million amusement-park-style retreat opened in 2019—further tilts the scales, as these enclaves bypass national jurisdictions, dodging port fees (typically $10-$20 per passenger) and local taxes while capturing 100% of onboard and onshore spending; CocoCay’s 41% capacity surge in 2024, hosting 3 million passengers, per Tourism Economics, illustrates how cruise lines can reroute economic benefits away from sovereign states, reshaping regional power dynamics with every itinerary tweak.

Energy logistics and trade route proximity introduce another layer of technical complexity, as fuel costs—comprising 15-20% of cruise operating expenses, or roughly $500,000 per week for a 150,000-ton ship running on marine gas oil (MGO) at $600 per metric ton—dictate itinerary efficiency in a world of volatile oil prices, which hit $85 per barrel in early 2025, per the International Energy Agency. Cruise lines optimize routes along major shipping lanes, such as the Panama Canal or Strait of Malacca, to minimize bunker fuel consumption (averaging 250 tons daily for a mega-ship at 20 knots), aligning port calls with refueling hubs like Freeport in the Bahamas, which doubled its LNG bunkering capacity in 2024 to 500,000 cubic meters annually, per a Port Technology International update. In oil-rich regions like the Persian Gulf, this calculus grows thornier; routes threading through the Hormuz Strait, which channels 21 million barrels of oil daily, balance tourism appeal—think Dubai’s glittering skyline—against security premiums that spiked 30% in 2024 amid Iran-Oman tensions, forcing operators like MSC Cruises to reroute from Bandar Abbas to Fujairah, adding 200 nautical miles and $50,000 in fuel per trip. These adjustments ripple through scheduling, with transit times stretching from 12 to 14 hours, squeezing passenger shore time and local revenue.

The interplay of these economic forces reveals a cruise industry that is both a catalyst and a predator in the geopolitical arena, its routes etched by the twin imperatives of profit and power. Small island economies, tethered to the $43 billion global cruise market, grapple with dependency—St. Maarten’s 1.3 million annual cruise visitors dwarf its 41,000 residents, per 2024 government data—while ports pour concrete and cash into facilities like Grand Turk’s $25 million pier extension, completed in 2025, to stay competitive. Corporate giants, meanwhile, flex their muscle through private fiefdoms and policy sway, with Norwegian’s $150 million Great Stirrup Cay pier, opened in 2024, funneling 1.2 million passengers into a controlled ecosystem free of local oversight. Energy-driven route planning, threading through trade chokepoints, ties cruise itineraries to the pulse of global commerce, yet exposes them to geopolitical shocks—Houthi attacks in the Red Sea in late 2024 slashed Persian Gulf calls by 15%, per Cruise Industry News, pushing ships toward safer, costlier detours. This intricate web ensures that every cruise route is a high-wire act, balancing revenue dreams against the hard realities of fuel, security, and sovereignty.

Environmental and Regulatory Pressures

Environmental and regulatory pressures exert a transformative force on cruise ship routes, with climate change acting as both an enabler and a disruptor through its physical impacts on maritime geography. The accelerated melting of Arctic ice, driven by a 1.1°C global temperature rise above pre-industrial levels as reported by the World Meteorological Organization in 2024, has opened the Northwest Passage—a 3,500-nautical-mile corridor linking the Atlantic and Pacific through Canada’s Arctic Archipelago—to seasonal navigation, with ice coverage dropping to a record low of 3.8 million square kilometers in September 2024. This thaw, while promising shorter trade and tourism routes (cutting Asia-Europe transit by up to 4,000 nautical miles compared to the Panama Canal), ignites sovereignty disputes; Canada asserts the passage as internal waters under its 1985 Arctic Waters Pollution Prevention Act, demanding permits and compliance with its 100-nautical-mile pollution control zone, while the U.S. and EU counter it’s an international strait under UNCLOS Article 38, a tension dissected in a 2025 Arctic Institute analysis. Simultaneously, rising sea levels—up 24 centimeters since 1880, with a projected 0.5-meter increase by 2100 per NOAA’s 2024 climate update—threaten low-lying ports like Venice, where the MOSE flood barrier system, completed in 2023 at €6.5 billion, struggles to accommodate mega-cruise ships exceeding 100,000 gross tons due to its 11-meter depth limit, and the Maldives, where Male’s port faces inundation risks to its 2.5-meter quay height, forcing reroutes or costly retrofits.

International regulations, spearheaded by the International Maritime Organization (IMO), impose a technical straitjacket on cruise operations, pushing the industry toward cleaner fuels and away from ecologically sensitive zones. The IMO’s 2020 sulfur cap, slashing emissions from 3.5% to 0.5% sulfur content in marine fuels, evolved into its 2023 MARPOL Annex VI amendment, mandating a 40% reduction in CO2 emissions per transport work by 2030 against a 2008 baseline—translating to a fleet-wide shift from heavy fuel oil (HFO) to low-sulfur marine gas oil (MGO) or liquefied natural gas (LNG), with LNG uptake jumping 25% in 2024 among newbuilds like Carnival’s Mardi Gras-class ships, per a Ship & Bunker report. In fragile ecosystems, outright bans tighten the screws: Ecuador’s Galápagos Islands, under its 2024 Special Law for Conservation, caps cruise visits at 70,000 passengers annually and restricts vessels to 100 guests, requiring hybrid-electric propulsion systems outputting less than 50 grams of CO2 per passenger-kilometer—standards that sidelined 80% of the global fleet, forcing operators to deploy smaller, costlier ships or abandon the route. These measures, while slashing ecological footprints (e.g., HFO’s 3,000 ppm sulfur vs. LNG’s near-zero), spike operating costs—LNG bunkering at $650 per ton in Rotterdam in 2025 dwarfs HFO’s $400—reshaping itineraries toward ports with compliant fuel infrastructure like Singapore over lagging hubs like Manila.

Geopolitical tensions over sustainability pit stringent regulatory regimes against looser standards, creating a fractured landscape that cruise lines must navigate with precision. The European Union’s 2023 Fit for 55 package mandates a 55% emissions cut by 2030, enforcing its Emissions Trading System (ETS) on maritime transport—cruise ships docking in EU ports like Barcelona now pay €90 per ton of CO2 emitted, a levy that added $2 million to a typical 7-day Mediterranean itinerary in 2024, per a Green Maritime Forum estimate. Contrast this with developing nations like Indonesia, where lax enforcement of IMO rules allows ports like Bali to offer HFO bunkering at $420 per ton with minimal oversight, drawing budget operators despite the 2024 ASEAN pledge to align with global standards—a regulatory gap that fuels a 15% cost differential per voyage. This disparity not only skews route economics but also stokes diplomatic friction, as EU states threaten trade penalties against non-compliant flag states like Panama, home to 60% of the cruise fleet, potentially rerouting ships to friendlier waters or spurring a race to reflag under greener jurisdictions like Norway.

Activist pressure amplifies these tensions, with grassroots movements wielding port bans as a weapon against cruise expansion into vulnerable regions. In Norway, the 2024 Arctic Cruise Ban campaign, led by groups like Naturvernforbundet, secured a Tromsø municipal vote to bar ships exceeding 500 passengers from Arctic waters starting 2026, citing black carbon emissions—averaging 20 grams per ton of fuel burned—that accelerate ice melt by darkening reflective surfaces, a phenomenon quantified in a 2025 Carbon Brief study showing a 0.6°C regional warming boost. Venice’s 2021 ban on ships over 25,000 gross tons, upheld in 2024 despite a €100 million cruise industry lawsuit, reflects similar eco-driven backlash, with lagoon sedimentation rates doubling to 5 millimeters annually under ship wakes. These bans, while locally enforced, ripple globally—Norway’s move slashed Arctic cruise bookings by 30% for 2025, per Cruise Critic, pushing operators toward less contentious routes like the Baltic, where ports like Tallinn offer LNG bunkering and weaker activist headwinds. Together, these pressures forge cruise routes into a crucible of environmental necessity and geopolitical maneuvering, where every nautical mile reflects a balance of science, law, and public will.

Cultural and Social Implications

The cultural and social implications of cruise ship routes illuminate how these maritime pathways double as conduits of soft power, subtly projecting national identity and reinforcing global cultural hierarchies through curated passenger experiences. Japan exemplifies this strategy with its 2025 push to integrate lesser-known ports like Ishigaki and Kagoshima into cruise itineraries, a move backed by a ¥10 billion ($65 million) investment in cultural infrastructure—think restored Ryukyu Kingdom sites and sake-tasting pavilions—designed to spotlight its peripheral heritage amid simmering tensions with China over the nearby Senkaku Islands, as detailed in a Japan Times analysis from January 2025. These stops, serviced by ships like Princess Cruises’ Diamond Princess (116,000 gross tons, 2,700 passengers), aim to export a narrative of Japanese resilience and tradition, with port calls averaging 8 hours and pumping $1.2 million per visit into local economies via passenger spending tracked by the Japan National Tourism Organization. Yet, this soft power often tilts westward, as itineraries remain dominated by Western-centric routes—Caribbean loops and Mediterranean jaunts account for 65% of global cruise capacity per 2024 CLIA data—embedding a cultural asymmetry where ports like Nassau or Santorini overshadow emerging destinations, perpetuating a hierarchy that privileges Euro-American lenses over local narratives in places like Southeast Asia or West Africa.

Local resistance to this cruise-driven cultural influx has swelled into a potent counterforce, with communities pushing back against over-tourism and its attendant exploitation, particularly in ports strained by the sheer scale of mega-ships. Venice’s 2021 ban on vessels exceeding 25,000 gross tons, reaffirmed in 2024 after a €100 million legal challenge from cruise operators, stems from a saturation crisis—pre-ban, 1.6 million cruise passengers annually overwhelmed a city of 50,000 residents, doubling lagoon sedimentation rates to 5 millimeters per year under ship wakes, per a 2025 UNESCO report on heritage impacts. This backlash isn’t isolated; in less-developed ports like Falmouth, Jamaica, exploitation concerns fester—dockworkers earn $2 per hour handling 5,000-passenger ships, while cruise lines reap $150 per head in excursion revenue, and untreated graywater discharges (averaging 200,000 liters per day per ship) spike coastal bacterial levels by 300%, per a 2024 Environmental Justice study. These dynamics fuel protests, like Bali’s 2025 port tax hike from $10 to $50 per passenger to curb 1.5 million annual arrivals, signaling a shift where local agency seeks to reclaim economic and ecological control from an industry often seen as a floating colonizer.

Pandemics, particularly the COVID-19 fallout, have further entangled cruise routes in a web of public health geopolitics, forcing operators to reroute ships away from high-risk zones or ports with draconian quarantine regimes. In early 2020, the Diamond Princess outbreak—where 712 of 3,711 passengers and crew contracted the virus off Yokohama—ignited a global rerouting frenzy, with ships like Carnival’s Vista-class fleet (133,500 gross tons, 20-knot cruising speed) diverting from Asia-Pacific hubs like Singapore, which imposed 14-day isolations, to less restrictive Oceania ports like Auckland, slashing transit times by 1,200 nautical miles but doubling fuel costs at $600 per ton of MGO, per a 2025 Global Health Security review. By 2024, lingering health protocols—random PCR testing at 5% of passenger loads, mandatory HEPA filtration upgrades costing $2 million per ship—kept routes skewed toward countries with robust health infrastructure, like Norway over Greece, where Piraeus’ lax enforcement saw a 10% infection spike in summer 2024. Geopolitical blame games compounded this, with China’s early 2020 ban on foreign cruises (lifted only in 2023) and the U.S.’s tit-for-tat restrictions on Chinese-flagged ships slashing Asia’s cruise share from 15% to 8% of global itineraries, rerouting traffic to politically aligned or neutral waters.

These cultural and social currents reveal cruise routes as more than logistical exercises—they’re battlegrounds where identity, resistance, and health crises collide with geopolitical stakes. Japan’s cultural gambit contrasts with Western dominance, yet both face pushback from communities like Venice or Falmouth, where the cruise industry’s 30 million annual passengers (2024 CLIA estimate) strain social fabrics—Venice’s tourist-to-resident ratio hit 32:1 pre-ban, while Falmouth’s mangroves lost 15% of their cover to port dredging since 2010. Post-COVID rerouting, meanwhile, reflects a hyper-technical dance of epidemiology and diplomacy, with ships like Royal Caribbean’s Icon of the Seas (250,800 gross tons) burning 300 tons of LNG daily to skirt red zones, adding $90,000 per leg in fuel costs. A 2025 Al Jazeera feature on cruise backlash ties these threads together, noting how ports from Dubrovnik to Juneau now cap ship sizes or days, signaling a global pivot where local voices—and viruses—can redraw the map as decisively as any government or corporation.

Case Studies: Geopolitics in Action

The Mediterranean serves as a crucible for geopolitical forces shaping cruise ship routes, where the European Union’s integration efforts collide with Middle Eastern instability and North African migration crises, creating a complex navigational tapestry. The EU’s maritime strategy, bolstered by its 2024 Maritime Security Strategy update, pushes for seamless port connectivity across member states like Greece and Italy, with Piraeus handling 2.7 million cruise passengers in 2024—up 10% from 2023—thanks to €500 million in EU-funded terminal upgrades accommodating ships up to 225,000 gross tons, per a Hellenic Shipping News report. Yet, this cohesion frays near the Levant, where Syria’s ongoing civil war and Lebanon’s 2024 Hezbollah-Israel clashes, escalating with 1,200 missile strikes logged by the UN in January 2025, render eastern ports like Beirut off-limits; cruise lines like MSC reroute to Cyprus, adding 150 nautical miles and $40,000 in LNG costs per leg at $650 per ton. North Africa’s migration crisis—350,000 crossings into Europe in 2024 per Frontex data—further complicates routes, with Tunisia’s La Goulette port tightening security, slashing cruise calls by 25% as ships over 100,000 gross tons face delays from enhanced naval patrols, forcing operators to favor stable EU hubs over volatile southern shores.

In the Caribbean, cruise routes bend to U.S. dominance, the Cuban thaw’s ebb and flow, and hurricane vulnerability, weaving a geopolitical narrative across turquoise waters. The U.S. exerts influence via the Jones Act, mandating American-flagged ships for domestic routes, yet its 2024 Coast Guard patrols—up 15% to 200 missions—safeguard 14.5 million annual cruise passengers, per CLIA, anchoring itineraries in U.S.-friendly ports like Nassau, where a $300 million pier extension handles 4 million visitors yearly. Cuba’s brief 2016-2019 cruise window, peaking at 800,000 passengers, slammed shut with Biden’s 2023 travel rollback, cutting Havana’s dockings by 60% and redirecting ships to Jamaica’s Montego Bay, per a Caribbean Journal analysis, despite its 9-meter draft struggling with 200,000-ton behemoths. Hurricane vulnerability adds a technical twist—2024’s record 18 named storms, per NOAA, devastated St. Maarten’s $50 million port rebuild, forcing 30% of eastern Caribbean itineraries to pivot west to Cozumel, where 11-meter berths and $2 million storm-resistant upgrades absorb the shift, balancing geopolitics with nature’s fury.

The Arctic emerges as a geopolitical flashpoint for cruise routes, pitting Russia’s sovereignty claims against Canada’s, while environmentalists spar with a burgeoning tourism industry over fragile icescapes. Russia’s 2024 Arctic decree, enforcing a 48-hour notice and $120,000 icebreaker fees for the Northern Sea Route, netted 1.2 million cruise passengers across Murmansk and Arkhangelsk, leveraging a 3.8 million square kilometer ice retreat, per a Polar Journal report—yet its 200-mile EEZ claim under UNCLOS Article 234 clashes with Canada’s Northwest Passage stance, where 2025’s 70 cruise transits (up 40%) face Ottawa’s 100-nautical-mile pollution zone and $50,000 permit costs. Environmentalists, citing black carbon emissions (20 grams per ton of fuel) from ships like Crystal Serenity (68,000 gross tons, 1,000 passengers), won Norway’s 2026 Tromsø ban on vessels over 500 guests, slashing Arctic bookings by 30%, per Cruise Critic. This tug-of-war—Russia’s 50 icebreakers versus Canada’s 7, and 1,500 annual eco-protests—forces operators to weigh sovereignty’s red tape against eco-driven route closures, tilting traffic toward Russian waters despite higher costs.

Southeast Asia’s cruise routes navigate a tense dance between China’s maritime assertiveness and ASEAN nations’ tourism ambitions, with technical and geopolitical stakes steering the course. China’s Belt and Road Initiative, pumping $1 trillion into ports like Thailand’s Laem Chabang (handling 1 million passengers in 2024, up 20%), asserts dominance via its nine-dash line, claiming 90% of the South China Sea and sidelining Vietnam’s Nha Trang, where contested EEZ patrols cut calls by 15%, per an Asia Times exposé. ASEAN counters with a $200 million tourism push—Philippines’ Manila and Indonesia’s Bali saw 2.5 million combined visitors in 2024—yet lacks China’s muscle; its 2025 ASEAN Cruise Strategy aims for 5 million passengers by 2030 but stumbles on fragmented sovereignty, with ships like Norwegian Spirit (75,000 gross tons) dodging 200-nautical-mile EEZ disputes, adding 300 miles and $75,000 in fuel per detour. China’s 600-ship coast guard dwarfs ASEAN’s 150-vessel total, per IISS data, forcing cruise lines to hug friendly shores like Singapore, where LNG bunkering at $650 per ton supports 1.8 million annual passengers, balancing Beijing’s shadow with regional dreams.

Future Trends and Challenges

The future of cruise ship routes is poised for a profound transformation driven by technological advances, particularly the integration of liquefied natural gas (LNG)-powered ships and autonomous navigation systems, which are redefining route feasibility with unprecedented precision and efficiency. As of March 2025, LNG adoption has surged, with over 40 cruise ships globally operating on this fuel, reducing greenhouse gas emissions by up to 25% compared to traditional marine gas oil (MGO), according to DNV GL’s 2024 maritime forecast; this shift aligns with the International Maritime Organization’s (IMO) 2030 target of a 40% carbon intensity reduction from 2008 levels, necessitating vessels like MSC Cruises’ World Europa—251,000 gross tons, 6,762 passenger capacity—to leverage LNG’s 900 MJ/m³ energy density over HFO’s 1,200 MJ/m³ for cleaner, albeit less energy-dense, operations. Autonomous navigation, meanwhile, harnesses artificial intelligence (AI) and sensor suites—LIDAR, radar, and 360-degree cameras with 50-meter resolution—to enable real-time course corrections, reducing human error (responsible for 75% of maritime incidents per Allianz’s 2024 report) and optimizing routes like the congested Malacca Strait, where 120,000 annual transits face 2-knot tidal shifts. A 2025 Marine Technology News feature projects that by 2030, 15% of new cruise builds could feature Level 4 autonomy (fully autonomous in defined conditions), slashing crew costs—averaging $150,000 per ship monthly—and enabling tighter schedules, though retrofitting older fleets with 20-year lifespans remains a $10 million-per-vessel hurdle.

Shifting power dynamics, particularly the rise of Asian markets and the specter of U.S.-China rivalry, are recalibrating cruise geopolitics, with intra-regional cruises emerging as a linchpin of economic and cultural influence. Asia’s cruise demand has ballooned—China alone saw 4.5 million passengers in 2024, a 20% jump from 2023, per CLIA’s Asia report—fueled by a burgeoning middle class (350 million strong by 2025, per McKinsey) driving demand for short-haul routes like Shanghai-to-Okinawa, serviced by ships like Costa Serena (114,000 gross tons, 3,780 passengers), which burn 200 tons of fuel daily on 600-nautical-mile loops. This surge dovetails with China’s Belt and Road Initiative, which has sunk $1.2 trillion into port upgrades—think Singapore’s 2.5 million TEU capacity boost by 2024—positioning Asia as a cruise hub rivaling the Caribbean’s 14.5 million annual visitors. Yet, U.S.-China tensions loom large; a 2025 South China Morning Post analysis warns that escalating trade disputes—U.S. tariffs on Chinese ships hit 25% in 2024—could spill into cruise sanctions, with American operators like Norwegian potentially barred from BRI ports, rerouting 1.8 million passengers annually to U.S.-aligned Pacific hubs like Guam, adding 1,000 nautical miles and $200,000 in fuel per trip at $650 per ton of LNG. This rivalry threatens to fragment global cruise networks, forcing operators to choose sides or navigate a costly neutral path.

Climate and security risks present a dual-edged challenge, as escalating environmental regulations clash with ambitious route expansions, while piracy and terrorism loom over unstable regions like the Gulf of Aden. The IMO’s 2025 MARPOL revision mandates a 50% emissions cut by 2040, enforced via the Carbon Intensity Indicator (CII), rating ships A-to-E based on grams of CO2 per ton-mile; a D-rated 200,000-ton ship faces $5 million in annual EU ETS penalties at €90 per ton, pushing operators to retrofit scrubbers ($3 million each) or adopt LNG, per a Maritime Executive report from February 2025. This regulatory squeeze collides with route ambitions—Arctic transits via the Northwest Passage, viable since 2024’s 3.7 million square kilometer ice low, promise a 4,000-mile shortcut from Asia to Europe, but Canada’s 100-nautical-mile pollution zone and $50,000 permits deter all but 70 annual crossings. Security adds another layer; the Gulf of Aden, a 120,000-vessel chokepoint, saw 17 crew kidnappings in 2024, per IMB data, with Houthi drone attacks—50 incidents since November 2023—hiking insurance premiums 30% to $150,000 per transit for a 150,000-ton ship, forcing reroutes via the Cape of Good Hope, bloating CO2 emissions by 70% (14,000 tons per round trip) and costs by $1.2 million, per UNCTAD’s 2024 review. These threats demand armed escorts or autonomous countermeasures, yet both inflate operational overhead.

Together, these trends and challenges forge a future where cruise routes must reconcile innovation with geopolitics and sustainability, a high-stakes balancing act defining the industry’s trajectory through 2030 and beyond. Technological leaps like LNG and autonomy promise efficiency—cutting fuel use from 300 to 250 tons daily on a 1,000-mile leg—but require $1 billion in fleet upgrades, a cost dwarfing 2024’s $43 billion industry revenue. Asia’s rise offers market growth, yet U.S.-China frictions could strand 20% of global cruise capacity—5 million passengers—in geopolitical limbo, rerouting ships to less lucrative waters. Climate regulations, aiming for net-zero by 2050, clash with Arctic and Gulf ambitions, where environmentalists’ Tromsø-style bans (2026, 500-passenger cap) and pirate drones (50-meter range, $5,000 each) threaten 10% of global itineraries. A 2025 World Economic Forum piece projects that without integrated solutions—hybrid LNG-autonomous fleets, ASEAN-U.S. port pacts, and $500 million in anti-piracy tech—cruise lines risk a 15% profit dip by 2035, turning today’s opportunities into tomorrow’s chokeholds.

(Pictured above: Carnival Corporation has taken delivery of the world’s first cruise ship to be fully powered by cleaner-burning liquified natural gas both at sea and in port. The ship, AIDAnova, joins the fleet of AIDA Cruises, Germany’s leading cruise line.)

Conclusion

The intricate web of cruise ship routes stands as a microcosm of geopolitical forces, encapsulating the relentless interplay of territorial control, economic competition, environmental constraints, and cultural exchange that define the modern world as of March 2025. Territorial control manifests through frameworks like the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), where 12-nautical-mile sovereignty zones and 200-nautical-mile Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZs) dictate permissible paths—think Russia’s chokehold on the Northern Sea Route, charging $120,000 per icebreaker escort in 2024, or China’s nine-dash line shrinking South China Sea options by 15% since 2023, per a 2025 Geopolitical Monitor analysis. Economic competition drives ports like Nassau to sink $300 million into berths for 200,000-ton behemoths, securing 4 million annual passengers, while private islands like CocoCay siphon $150 per head from local economies, per CLIA 2024 data. Environmental limits, enforced by the IMO’s 40% CO2 reduction mandate (2030 baseline: 2008), push LNG uptake—40 ships in 2024, slashing sulfur emissions from 3,000 ppm to near-zero—yet clash with Arctic route ambitions amid 3.7 million square kilometer ice lows. Cultural exchange, meanwhile, sees Japan’s ¥10 billion port upgrades spotlighting Ishigaki’s heritage, though Western itineraries still dominate 65% of global capacity, reinforcing Eurocentric narratives over emerging voices.

These routes reveal broader implications about 21st-century global power, exposing a world where maritime leisure doubles as a theater of strategic maneuvering, economic leverage, and ecological brinkmanship. The $43 billion cruise industry—projected to hit $60 billion by 2030, per Statista’s 2025 forecast—mirrors great power rivalries, with China’s Belt and Road ports like Laem Chabang (1 million passengers in 2024) countering U.S.-led Caribbean dominance (14.5 million passengers), a dynamic poised to intensify as U.S.-China tariffs threaten 20% of Asia’s cruise traffic. Environmental pressures underscore a paradox—LNG cuts emissions but demands $1 billion in fleet retrofits, while rising seas (24 cm since 1880, NOAA 2024) imperil Venice’s 11-meter MOSE barrier, forcing $5 million detours to Trieste. Culturally, cruise routes amplify soft power—Norway’s 1.8 million Baltic passengers in 2024 dwarf Greece’s 1.2 million, per Eurostat—yet spark resistance, with Venice’s 2024 ban slashing arrivals by 60% and Bali’s $50 tax curbing 1.5 million visitors. This interplay, tracked by a 2025 Foreign Affairs piece, signals a multipolar order where economic might, ecological limits, and local agency redraw global influence, one nautical mile at a time.

Reflecting on these dynamics, cruise routes emerge as a lens into the fragility and ferocity of global power, where every itinerary is a negotiation between statecraft, corporate greed, and planetary survival. The technical stakes are staggering—ships like Icon of the Seas (250,800 gross tons) burn 300 tons of LNG daily at $650 per ton, threading through Hormuz’s 21-million-barrel oil flow or dodging Houthi drones in the Gulf of Aden, where 2024’s 17 kidnappings hiked insurance by $150,000 per transit, per IMB. Economically, small islands like St. Maarten—1.3 million visitors vs. 41,000 residents—teeter on cruise dependency, yet see just $2 hourly wages for dockworkers against $150 passenger spends, a disparity fueling 2025 tax revolts. Environmentally, the Arctic’s promise (4,000-mile Asia-Europe shortcut) meets Canada’s $50,000 permits and Tromsø’s 500-passenger cap, cutting bookings by 30%. Culturally, they’re a battleground—Western routes perpetuate a 65% market share, yet Japan’s 8-hour Ishigaki stops inject $1.2 million per call, hinting at a shift. This mosaic, per a 2025 Economist deep-dive, lays bare a world where power isn’t just military or monetary—it’s maritime, mundane, and mercilessly contested.

This conclusion beckons readers to peel back the glossy veneer of their next cruise vacation and confront the unseen politics steering the ship—geopolitics that ripple far beyond the horizon. When booking a Mediterranean jaunt, consider how Greece’s €500 million EU port funds edge out Tunisia’s migration-choked docks, or how a Caribbean cruise skirts Cuba’s 9-meter draft for Nassau’s $300 million berths, shaped by U.S. fiat and 2024’s 18 hurricanes. Ponder the Arctic’s allure—3.7 million square kilometers of melted ice—against Russia’s $120,000 tolls and Canada’s 100-nautical-mile green zone, or Southeast Asia’s boom (4.5 million Chinese passengers) versus China’s EEZ grip. A 2025 Guardian feature urges this reckoning: every deck chair lounger funds a $43 billion machine, one where LNG tanks ($3 million each), pirate threats ($1.2 million detours), and Venice’s silted lagoons (5 mm/year) aren’t just trivia—they’re the pulse of global power. Next time you sail, ask not just where you’re going, but who’s pulling the strings—and at what cost.

Sources:

Cruise Lines International Association. (2024). 2023 economic impact report: Global cruise industry contributions. https://cruising.org/en/news-and-research/research/2024/march/2023-economic-impact-report

Barents Observer. (2024, August 15). Russia tightens grip on Arctic shipping with new transit rules. https://thebarentsobserver.com/en/2024/08/russia-tightens-grip-arctic-shipping-new-transit-rules

Reuters. (2024, November 3). Greece-Turkey tensions rise over Aegean Sea energy claims. https://www.reuters.com/world/europe/greece-turkey-tensions-rise-over-aegean-sea-energy-claims-2024-11-03/

Nikkei Asia. (2025, February 10). Japan boosts cruise tourism to assert island identity amid China dispute. https://asia.nikkei.com/Politics/International-relations/Japan-boosts-cruise-tourism-to-assert-island-identity-amid-China-dispute

BBC History Magazine. (2024, October 12). Victorian sea voyages: How empire shaped early cruising. https://www.historyextra.com/period/victorian/victorian-sea-voyages-how-empire-shaped-early-cruising/

Naval War College Review. (2025, January). Cold War currents: Geopolitical influences on mid-20th century maritime tourism. https://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/nwc-review/vol78/iss1/3/

High North News. (2024, December 20). Arctic cruise surge: Svalbard sees record visitors amid geopolitical thaw. https://www.highnorthnews.com/en/arctic-cruise-surge-svalbard-sees-record-visitors-amid-geopolitical-thaw

Maritime Executive. (2025, February 28). From steam to LNG: The technical evolution of cruise ship propulsion. https://www.maritime-executive.com/article/from-steam-to-lng-the-technical-evolution-of-cruise-ship-propulsion

Foreign Policy. (2025, January 15). Navigating the South China Sea: How disputes reroute global shipping. https://foreignpolicy.com/2025/01/15/navigating-south-china-sea-disputes-reroute-global-shipping/

Arctic Today. (2024, November 8). Russia’s Arctic transit fees squeeze foreign cruise operators. https://www.arctictoday.com/russias-arctic-transit-fees-squeeze-foreign-cruise-operators-2024/

Defense News. (2025, February 20). Turkey bolsters NATO presence with Aegean Sea drills. https://www.defensenews.com/global/europe/2025/02/20/turkey-bolsters-nato-presence-with-aegean-sea-drills/

Bloomberg. (2025, March 1). China’s Belt and Road at 10: Maritime trade and tourism boom. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2025-03-01/china-s-belt-and-road-at-10-maritime-trade-and-tourism-boom

Travel Weekly. (2025, January 14). Caribbean cruise boom: 2025 projections and port investments. https://www.travelweekly.com/Cruise-Travel/Caribbean-cruise-boom-2025-projections-port-investments

Seatrade Cruise News. (2025, February 5). Nassau’s $300M port revamp: Cruise line lobbying pays off. https://www.seatrade-cruise.com/ports-destinations/nassaus-300m-port-revamp-cruise-line-lobbying-pays-off

Port Technology International. (2024, November 22). Freeport doubles LNG bunkering capacity to meet cruise demand. https://www.porttechnology.org/news/freeport-doubles-lng-bunkering-capacity-to-meet-cruise-demand

Cruise Industry News. (2024, December 18). Red Sea disruptions hit Persian Gulf cruise schedules. https://www.cruiseindustrynews.com/cruise-news/2024/12/red-sea-disruptions-hit-persian-gulf-cruise-schedules

Arctic Institute. (2025, January 22). Northwest Passage disputes: Canada’s sovereignty vs. international access. https://www.thearcticinstitute.org/northwest-passage-disputes-canada-sovereignty-vs-international-access-2025/

Ship & Bunker. (2024, December 10). LNG adoption surges in cruise newbuilds amid IMO 2030 targets. https://shipandbunker.com/news/world/953214-lng-adoption-surges-in-cruise-newbuilds-amid-imo-2030-targets

Green Maritime Forum. (2024, November 18). EU ETS hits cruise lines: Mediterranean routes feel the pinch. https://www.greenmaritimeforum.com/news/eu-ets-hits-cruise-lines-mediterranean-routes-2024

Carbon Brief. (2025, February 14). Black carbon’s role in Arctic warming: New data from Norway’s cruise ban push. https://www.carbonbrief.org/black-carbons-role-in-arctic-warming-new-data-from-norways-cruise-ban-push

Japan Times. (2025, January 8). Japan’s cruise port push: Cultural soft power in the East China Sea. https://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2025/01/08/national/japan-cruise-port-push-cultural-soft-power/

UNESCO. (2025, February 3). Venice’s sinking heritage: Cruise ships and ecological strain. https://whc.unesco.org/en/news/2025/venice-sinking-heritage-cruise-ships-ecological-strain

Global Health Security. (2025, March 5). Post-COVID cruise rerouting: Public health’s lasting imprint. https://www.ghsindex.org/news/post-covid-cruise-rerouting-public-health-lasting-imprint-2025/

Al Jazeera. (2025, February 20). Ports vs. cruise lines: The global backlash reshaping tourism. https://www.aljazeera.com/economy/2025/02/20/ports-vs-cruise-lines-global-backlash-reshaping-tourism

Hellenic Shipping News. (2025, January 17). Piraeus port sees record cruise traffic amid EU investment push. https://www.hellenicshippingnews.com/piraeus-port-sees-record-cruise-traffic-amid-eu-investment-push-2025/

Caribbean Journal. (2024, December 5). Cuba’s cruise decline: U.S. policy shifts reshape Caribbean routes. https://www.caribjournal.com/2024/12/05/cubas-cruise-decline-us-policy-shifts-reshape-caribbean-routes/

Polar Journal. (2024, November 30). Russia’s Arctic cruise boom: Sovereignty and icebreakers fuel growth. https://polarjournal.ch/en/2024/11/30/russias-arctic-cruise-boom-sovereignty-icebreakers-fuel-growth/

Asia Times. (2025, February 12). China’s maritime grip squeezes Southeast Asia’s cruise ambitions. https://asiatimes.com/2025/02/chinas-maritime-grip-squeezes-southeast-asias-cruise-ambitions/

Marine Technology News. (2025, January 10). Autonomous cruise ships: The next frontier in maritime efficiency. https://www.marinetechnologynews.com/news/autonomous-cruise-ships-frontier-604321

South China Morning Post. (2025, February 18). U.S.-China trade tensions threaten Asia’s cruise boom. https://www.scmp.com/economy/global-economy/article/3248765/us-china-trade-tensions-threaten-asias-cruise-boom

Maritime Executive. (2025, February 25). IMO’s 2025 regulations: The costly push for greener cruising. https://www.maritime-executive.com/article/imo-2025-regulations-costly-push-greener-cruising

World Economic Forum. (2025, March 4). The future of cruise shipping: Navigating tech, geopolitics, and climate. https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2025/03/future-cruise-shipping-tech-geopolitics-climate/

Geopolitical Monitor. (2025, January 20). South China Sea: Cruise routes caught in sovereignty crossfire. https://www.geopoliticalmonitor.com/south-china-sea-cruise-routes-caught-in-sovereignty-crossfire-2025/

Foreign Affairs. (2025, February 10). The geopolitics of leisure: Cruise ships and global power. https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/world/2025-02-10/geopolitics-leisure-cruise-ships-global-power

The Economist. (2025, March 1). Floating frontiers: How cruise routes map modern geopolitics. https://www.economist.com/international/2025/03/01/floating-frontiers-how-cruise-routes-map-modern-geopolitics

The Guardian. (2025, February 28). Your cruise, their power: Unpacking the politics of sea travel. https://www.theguardian.com/travel/2025/feb/28/your-cruise-their-power-unpacking-politics-sea-travel