The World’s Largest Polluter: China’s Role in Global Climate Change

The High Price of Progress: China’s Impact on Global Ecology

TL;DR:

China: World's Largest Polluter

Emits ~30% of global CO₂, primarily from coal.

Air pollution causes significant public health crises.

Renewable energy investments growing but coal dependence remains.

Environmental Policies in China

Stricter air pollution controls and carbon markets implemented.

Leading in solar & wind energy but struggles with policy enforcement.

Goal: Peak emissions by 2030, carbon neutrality by 2060.

Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) & Environment

Massive infrastructure projects causing deforestation & biodiversity loss.

High carbon footprint, with continued coal investments abroad.

"Green BRI" promoted, but implementation falls short.

Global Criticism & China's Response

NGOs & governments warn of environmental harm from BRI.

Some countries cancel or renegotiate BRI projects over sustainability concerns.

China defends BRI as a vehicle for green tech, but coal reliance undermines credibility.

Future Challenges & Opportunities

Needs stricter environmental enforcement & greener infrastructure.

Balancing economic growth with sustainability remains difficult.

China's climate policies will significantly impact global climate goals.

And now for the Deep Dive….

Introduction

China's role in global environmental discussions is dual-edged, marked by its status as the world's largest emitter of greenhouse gases and its extensive influence through the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). The country's heavy reliance on coal for energy, contributing around 27% of global CO2 emissions, alongside industrial pollution significantly impacts air quality and public health. Urbanization and rapid industrialization have led to severe ecological degradation, positioning China at the heart of both the problem and potential solutions in the climate change narrative.

The BRI, intended to boost China's economic ties globally, has sparked environmental concerns due to its massive infrastructure projects. These projects, spanning from Southeast Asia to Africa, often lead to deforestation, biodiversity loss, and water management issues. While China has introduced the concept of a "Green BRI" to promote sustainable development, the practical implementation falls short, with many projects still not adhering to high environmental standards, leading to criticisms of exporting environmentally harmful practices.

Efforts to mitigate China's environmental footprint include policy reforms like stringent air pollution controls and a push towards renewable energy. However, the continued construction of coal plants, both domestically and abroad, complicates the narrative of sustainable development. China's commitment to international climate goals, like the Paris Agreement, alongside its innovations in green technology, offers hope for a shift towards sustainability. Yet, the balance between economic growth and environmental stewardship remains delicate, with China's future actions critical to global climate outcomes.

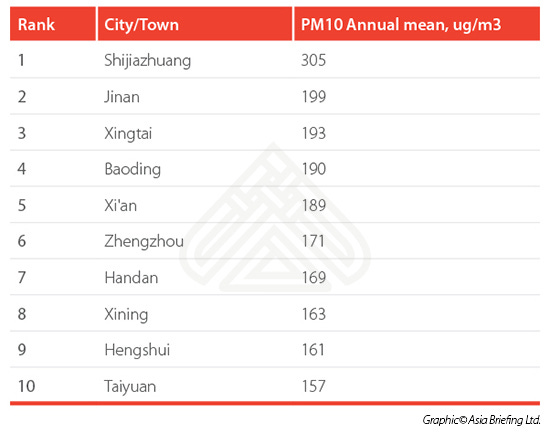

(Chart above: The top 10 most polluted Chinese cities, in terms of air pollution)

China as the World's Largest Polluter

China's position as the world's largest polluter is primarily defined by its massive carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions. In 2023, China emitted about 11.9 billion metric tons of CO2, which is significantly higher than any other nation, dwarfing the U.S. emissions, which stood at approximately 5.9 billion tons for the same year. This statistic places China at the forefront of global emissions, contributing roughly 30% to the world's total CO2 output. Over the last decade, China's emissions have not only been the highest but have also shown a steady increase, despite temporary dips due to economic slowdowns, like during the global health crisis. However, recent analyses indicate that while the growth rate of emissions has slowed, the absolute volume remains a major concern, with some sources suggesting a slight decrease in the growth rate due to policy interventions and technological advancements in renewable energy.

The primary source of China's pollution is its dependency on coal for energy production. Coal, being the most carbon-intensive fossil fuel, accounts for approximately 70% of China's electricity generation. This reliance on coal for power has deep roots in China's economic development strategy, providing cheap energy for industrial expansion but at a high environmental cost. Manufacturing and industrial processes also contribute significantly to China's pollution profile. The country's role as the "world's factory" has led to an extensive array of industries, from steel production to chemicals, which are not only energy-intensive but also emit various pollutants. Additionally, urban expansion and the accompanying growth in transportation have escalated emissions from vehicles and construction activities, further compounding air quality issues.

The environmental impact of China's pollution extends far beyond its borders, significantly contributing to global warming. The high volume of greenhouse gases emitted, particularly CO2, traps heat in the Earth's atmosphere, exacerbating the greenhouse effect. This contribution is so substantial that even incremental changes in China's emissions profile could influence global climate trends. Moreover, the emissions from China's industries, including sulfur dioxide, nitrogen oxides, and particulate matter, have direct and indirect effects on air quality. These pollutants not only contribute to climate change but also lead to health crises, with air pollution in China linked to millions of premature deaths annually, primarily from respiratory and cardiovascular diseases.

The trend in China's CO2 emissions over the last decade reflects a complex interplay of economic growth, policy interventions, and international commitments. While the last decade has seen an overall increase in emissions, recent years have shown signs of potential stabilization, or even slight dips, thanks to aggressive renewable energy adoption and efficiency improvements. For instance, China has become the global leader in solar and wind installations, aiming to peak its CO2 emissions by 2030 and achieve carbon neutrality by 2060. These targets, announced in 2020, reflect a significant policy shift towards sustainability, although the path to these goals involves overcoming entrenched coal dependency and managing the economic implications of transitioning away from fossil fuels.

The impact on air quality, particularly in urban areas, continues to be a pressing issue. Cities like Beijing and Shanghai frequently experience smog levels that far exceed WHO guidelines, with PM2.5 levels often recorded at hazardous concentrations. This not only affects human health but also visibility, leading to economic impacts through lost productivity and increased healthcare costs. The Chinese government has responded with the Air Pollution Prevention and Control Action Plan, which aims to significantly reduce these pollutants, but enforcement and effectiveness vary across different regions and industries.

Global climate models incorporate China's emissions as a critical variable. Given its size, any shift in China's emissions trajectory can influence global climate strategies and outcomes. For example, if China were to successfully decarbonize its energy sector, this could provide a substantial buffer for global carbon budgets aimed at keeping global warming below 1.5 degrees Celsius, as outlined by the Paris Agreement. However, current projections and the ongoing construction of new coal plants suggest a challenging path ahead, potentially locking in emissions for decades.

The health implications of China's pollution are stark, with studies linking high levels of air pollution to increased incidences of lung cancer, heart disease, and stroke. The economic cost of these health effects is immense, with estimates suggesting billions in lost GDP due to health-related absences and treatment costs. This scenario underscores the urgency for China to integrate health considerations into its environmental policies, moving beyond economic metrics to evaluate the true cost of pollution.

While China's role as the largest polluter presents significant challenges to global climate stability, it also offers opportunities for leadership in climate action. The nation's recent policies and technological advancements in green energy indicate a potential shift, but the scale of change required is monumental. The interplay between economic development, energy policy, and environmental impact will continue to shape not only China's future but also global environmental narratives.

Environmental Policy in China

The historical context of China's environmental policy is marked by a significant shift from a focus on rapid industrialization to increasing environmental consciousness. Post-1978 economic reforms set China on a path of extraordinary growth, primarily fueled by heavy industry and coal, with environmental considerations often sidelined. The environmental toll became evident by the late 20th century, with severe pollution incidents like the 1998 Yangtze River floods and Beijing's smog crises prompting a reconsideration of environmental strategies. This awareness was further propelled by public demand for cleaner living conditions and international pressure to join global environmental treaties, leading to policy evolution towards sustainability.

In recent years, China has implemented several key environmental policies, with the Air Pollution Prevention and Control Action Plan (APPCAP) launched in 2013 standing out as a landmark initiative. This plan aimed to reduce PM2.5 concentrations by 25% over five years in major cities, involving strict emission standards for industries, vehicle emissions control, and coal use restrictions. The policy also introduced regional coordination for pollution control, acknowledging that air pollution knows no administrative boundaries. Subsequent data showed significant improvements in air quality in many regions, though challenges persist in certain industrial zones and during peak pollution seasons.

Renewable energy has become a cornerstone of China's environmental policy. The government set ambitious targets for renewable energy, aiming to increase the proportion of non-fossil fuels in its energy mix to around 20% by 2025. By 2023, China had already surpassed many of its goals, becoming the world leader in solar and wind power installations. This push includes massive investments in hydroelectric projects, despite the controversies surrounding large-scale dam constructions and their ecological impact. The integration of these renewable sources into the national grid has been a technical challenge, leading to issues like grid congestion and renewable energy curtailment, where generated power cannot be consumed or stored effectively.

Carbon trading and emissions reduction strategies have also been pivotal in China's environmental policy framework. In 2021, China launched the world's largest carbon market, initially covering the power generation sector, with plans to expand to other high-emission industries. This system operates on a cap-and-trade principle, where companies can either reduce their emissions or buy permits from those who exceed their reduction targets. This market mechanism is intended to incentivize companies to innovate for lower emissions but faces challenges in terms of setting realistic caps, ensuring transparency, and preventing market manipulations.

However, these policies face significant enforcement issues. The vast geographical spread of China, coupled with the power of local governments, often results in uneven policy application. While national policies might be stringent, local authorities might prioritize economic development over environmental compliance, leading to lax enforcement or outright violations. This is exacerbated by the historical performance evaluations of local officials, which heavily weigh economic achievements over environmental stewardship.

The core challenge in China's environmental policy landscape is balancing economic growth with environmental protection. The country's economic model, which has lifted millions out of poverty, has been heavily reliant on energy-intensive industries. Shifting towards a green economy requires not just policy adjustments but also a cultural shift in how economic success is measured. The tension between maintaining GDP growth and adhering to environmental targets often manifests in compromises, where short-term economic gains might be favored over long-term ecological sustainability.

China's commitment to international climate agreements, like the Paris Agreement, adds another layer of complexity. While China has pledged to peak its carbon emissions before 2030 and achieve carbon neutrality by 2060, translating these commitments into actionable policy that aligns with economic realities is daunting. The transition involves rethinking energy policies, urban planning, and industrial practices, all while ensuring that the economic engine does not stall.

China's journey towards sustainable environmental policy is characterized by significant strides but also by ongoing struggles. The nation's capacity to innovate in green technology and policy frameworks will be crucial, but so will be the political will to enforce these policies uniformly and to navigate the economic implications of a greener path. The balance China achieves in this domain will not only shape its domestic landscape but also influence global environmental trends and the effectiveness of international climate efforts.

The Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) and Environmental Impact

The Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), launched by China in 2013, aims to recreate the ancient Silk Road through modern infrastructure development, enhancing trade routes and economic connectivity across more than 140 countries. Its geographical scope spans from East Asia to Europe, covering Africa, the Middle East, and beyond, with a focus on building a network that includes railways, highways, ports, and energy pipelines. The initiative's primary goals are to boost economic integration, increase trade, and foster political cooperation, but these ambitions come with significant environmental considerations due to the scale and nature of the projects involved.

Infrastructure development under the BRI often necessitates large-scale environmental changes, particularly in Southeast Asia where deforestation has become a pronounced issue. The construction of roads, railways, and industrial zones requires clearing vast swathes of forested land, which not only reduces carbon sequestration but also leads to habitat fragmentation. This deforestation impacts biodiversity, particularly in regions known for their rich ecosystems, like the Mekong Basin or the rainforests of Indonesia. The environmental toll includes not just loss of forest but also the degradation of soil quality and increased risk of landslides and floods due to altered landscapes.

The impact on biodiversity is a critical concern with BRI projects. Construction activities often intersect with areas designated as biodiversity hotspots, where species richness and endemism are particularly high. For instance, in Africa, the building of railways and highways can disrupt the migration paths of wildlife, potentially leading to population declines of already threatened species. Similarly, in Europe, projects near or through national parks could harm delicate ecosystems. The BRI's potential to introduce invasive species during construction and operation phases further threatens native biodiversity, a risk highlighted by studies showing how new infrastructure can act as pathways for biological invasions.

Water pollution and management issues are notably significant in Central Asia, where BRI projects like dams and pipelines affect transboundary water resources. The construction of dams, notably in the Mekong River, has altered water flows, impacting downstream countries' access to water for agriculture, fisheries, and domestic use. Pollution from construction sites, industrial operations, and increased shipping in newly developed ports can contaminate rivers and groundwater, affecting both local populations and aquatic life. This is compounded by poor regulatory frameworks in some BRI countries, which might not have the capacity or policies in place to manage such extensive environmental changes.

Analyzing specific case studies offers insight into the environmental-economic trade-offs of the BRI. The Hambantota Port in Sri Lanka, for example, has been both an economic boon and an environmental concern. While it has facilitated trade and attracted foreign investment, it has also led to habitat loss, increased coastal erosion, and potential water pollution from port activities. Similarly, the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) has seen significant infrastructure growth, particularly in energy production, but at the cost of environmental degradation. Coal power plants under CPEC have raised concerns about air quality and carbon emissions, potentially locking Pakistan into high-pollution energy pathways for decades.

In both cases, there's an evident tension between short-term economic gains and long-term environmental health. For Hambantota, the economic development has brought jobs and infrastructure, but at the potential expense of marine ecosystems and local livelihoods dependent on fishing. In CPEC, while rapid infrastructure development promises to uplift the economy, the environmental costs could manifest in health issues, loss of biodiversity, and challenges in meeting international climate commitments.

The environmental impact assessments (EIAs) for BRI projects have often been criticized for lacking rigor or being superficial. Many projects either bypass these assessments or conduct them with insufficient public consultation or transparency, leading to inadequate mitigation strategies. This has sparked international debate on the need for a standardized approach to environmental governance within the BRI framework, ensuring that development does not come at the expense of environmental integrity.

While the BRI holds the promise of economic development and global connectivity, its environmental implications are profound and multifaceted. Addressing these concerns requires not only better project planning and assessment but also a commitment from participating countries to incorporate sustainable practices into their development strategies. The balance between fostering economic growth and protecting the environment will be a defining challenge for the BRI moving forward, influencing its legacy in the context of global environmental stewardship.

(Pictured above: The Hambantota Port in Sri Lanka)

Global Criticism and Response

Global criticism of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) has been vocal, particularly from environmental NGOs. Organizations such as Greenpeace and the World Wildlife Fund have pointed out the potential for significant environmental degradation resulting from BRI projects. Their concerns include habitat destruction, increased carbon emissions, and the lack of robust environmental impact assessments. These NGOs advocate for stricter environmental standards and more transparent project planning, emphasizing that without these, the BRI could contribute to global biodiversity loss and accelerate climate change, particularly in regions with fragile ecosystems.

Countries hosting BRI projects have varied responses to these environmental concerns. Some nations, especially those in dire need of infrastructure development, see the economic benefits as outweighing immediate environmental costs. However, countries like Malaysia and Pakistan have voiced concerns over projects like the East Coast Rail Link and the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), respectively, where local environmental impacts have been significant. These countries have pushed for negotiations to include more sustainable practices or even canceled projects due to environmental or financial sustainability issues. This dynamic reflects a broader tension where economic desperation often leads to environmental compromises.

China, in defense of the BRI, has articulated its commitment to sustainable development. It argues that the initiative can be a vehicle for exporting green technology and practices, potentially improving environmental standards in less developed regions. Chinese officials often point to the "Green BRI" initiative, which promotes ecological civilization principles, green finance, and sustainable infrastructure. However, the practical application of these ideals is debated, with critics arguing that while the rhetoric is strong, the implementation often falls short, especially when economic returns are prioritized over environmental safeguards.

The Green BRI is one of several counterarguments China employs. This initiative includes policy documents like the "Guidance on Promoting Green Belt and Road" and commitments to reduce the carbon footprint of its projects. China has also engaged in international collaborations, such as the Belt and Road Initiative International Green Development Coalition, aiming to foster sustainable development among BRI countries. Yet, the effectiveness of these initiatives is debated, with some projects still involving high-pollution industries like coal, which contradicts green objectives.

The diplomatic and economic implications of China's environmental practices under the BRI are significant. On the diplomatic front, China's environmental policies influence its standing in global climate negotiations. Participation in international frameworks like the Paris Agreement requires China to demonstrate leadership in reducing emissions, both at home and through its international projects. However, the environmental impact of BRI projects has sometimes put China at odds with its international climate commitments, potentially affecting its credibility in global climate discussions.

Economically, the BRI presents trade-offs in international relations. Countries participating in BRI projects sometimes face a dilemma: accept the environmental risks for economic gains or resist and potentially lose out on development opportunities. This has led to what some describe as "debt-trap diplomacy," where environmental considerations might be sidelined for financial aid or infrastructure development. This situation can strain international relations, particularly when environmental degradation leads to public outcry or when projects do not yield the expected economic benefits, leading to increased scrutiny and criticism from both domestic populations and international observers.

Moreover, the BRI's environmental footprint influences China's international image. As global awareness of climate change grows, so does the scrutiny of China's role as a global player. Countries and international bodies are increasingly evaluating their partnerships with China based on environmental impacts, which can influence trade agreements, diplomatic relations, and global alliances. The push towards greener BRI projects could be seen as an attempt to mitigate some of these criticisms, but the slow pace of change and ongoing projects with high environmental costs continue to fuel debate.

The global discourse around the BRI's environmental impact is complex, involving a mixture of criticism, defense, and strategic responses. The challenge for China lies in reconciling its ambition for global leadership in both economic and environmental spheres. The way China navigates these criticisms and adapts its strategies will not only affect its international relations but also the global approach to sustainable development in the context of massive infrastructure initiatives.

Future Prospects and Potential Solutions

Global criticism of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) has been vocal, particularly from environmental NGOs. Organizations such as Greenpeace and the World Wildlife Fund have pointed out the potential for significant environmental degradation resulting from BRI projects. Their concerns include habitat destruction, increased carbon emissions, and the lack of robust environmental impact assessments. These NGOs advocate for stricter environmental standards and more transparent project planning, emphasizing that without these, the BRI could contribute to global biodiversity loss and accelerate climate change, particularly in regions with fragile ecosystems.

Countries hosting BRI projects have varied responses to these environmental concerns. Some nations, especially those in dire need of infrastructure development, see the economic benefits as outweighing immediate environmental costs. However, countries like Malaysia and Pakistan have voiced concerns over projects like the East Coast Rail Link and the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), respectively, where local environmental impacts have been significant. These countries have pushed for negotiations to include more sustainable practices or even canceled projects due to environmental or financial sustainability issues. This dynamic reflects a broader tension where economic desperation often leads to environmental compromises.

China, in defense of the BRI, has articulated its commitment to sustainable development. It argues that the initiative can be a vehicle for exporting green technology and practices, potentially improving environmental standards in less developed regions. Chinese officials often point to the "Green BRI" initiative, which promotes ecological civilization principles, green finance, and sustainable infrastructure. However, the practical application of these ideals is debated, with critics arguing that while the rhetoric is strong, the implementation often falls short, especially when economic returns are prioritized over environmental safeguards.

The Green BRI is one of several counterarguments China employs. This initiative includes policy documents like the "Guidance on Promoting Green Belt and Road" and commitments to reduce the carbon footprint of its projects. China has also engaged in international collaborations, such as the Belt and Road Initiative International Green Development Coalition, aiming to foster sustainable development among BRI countries. Yet, the effectiveness of these initiatives is debated, with some projects still involving high-pollution industries like coal, which contradicts green objectives.

The diplomatic and economic implications of China's environmental practices under the BRI are significant. On the diplomatic front, China's environmental policies influence its standing in global climate negotiations. Participation in international frameworks like the Paris Agreement requires China to demonstrate leadership in reducing emissions, both at home and through its international projects. However, the environmental impact of BRI projects has sometimes put China at odds with its international climate commitments, potentially affecting its credibility in global climate discussions.

Economically, the BRI presents trade-offs in international relations. Countries participating in BRI projects sometimes face a dilemma: accept the environmental risks for economic gains or resist and potentially lose out on development opportunities. This has led to what some describe as "debt-trap diplomacy," where environmental considerations might be sidelined for financial aid or infrastructure development. This situation can strain international relations, particularly when environmental degradation leads to public outcry or when projects do not yield the expected economic benefits, leading to increased scrutiny and criticism from both domestic populations and international observers.

Moreover, the BRI's environmental footprint influences China's international image. As global awareness of climate change grows, so does the scrutiny of China's role as a global player. Countries and international bodies are increasingly evaluating their partnerships with China based on environmental impacts, which can influence trade agreements, diplomatic relations, and global alliances. The push towards greener BRI projects could be seen as an attempt to mitigate some of these criticisms, but the slow pace of change and ongoing projects with high environmental costs continue to fuel debate.

The global discourse around the BRI's environmental impact is complex, involving a mixture of criticism, defense, and strategic responses. The challenge for China lies in reconciling its ambition for global leadership in both economic and environmental spheres. The way China navigates these criticisms and adapts its strategies will not only affect its international relations but also the global approach to sustainable development in the context of massive infrastructure initiatives.

Conclusion

In conclusion, China's environmental footprint, both domestically and through the Belt and Road Initiative, underscores its complex role in global climate discussions. As the world's largest polluter, China's heavy reliance on coal and its vast industrial sector continue to pose significant environmental challenges, affecting air quality, biodiversity, and global carbon emissions. While China has made notable strides in renewable energy, carbon trading, and pollution control policies, the scale of change required to align with international climate goals remains daunting.

The Belt and Road Initiative further complicates this narrative, as large-scale infrastructure projects bring both economic development and environmental concerns. Despite the promise of a "Green BRI," many projects still contribute to deforestation, biodiversity loss, and emissions, raising global scrutiny. China's response to international criticism has included policy adjustments and commitments to sustainable development, but implementation remains inconsistent.

Moving forward, the balance between economic growth and environmental responsibility will define China's role in the global sustainability movement. Strengthening enforcement of environmental policies, enhancing transparency in international projects, and accelerating the shift away from coal are critical steps for China to solidify its commitment to a greener future. The decisions China makes in the coming years will not only shape its domestic environmental landscape but also have profound implications for global climate stability.

Sources:

Zhang, X., et al. (2024). China's CO2 emissions in 2023. National Bureau of Statistics of China. Retrieved from http://www.stats.gov.cn/english/PressRelease/202401/t20240105_1952267.html

IEA. (2023). Coal 2023: Analysis and forecast to 2026. International Energy Agency. Retrieved from https://www.iea.org/reports/coal-2023

Wang, J. & Feng, K. (2023). China’s industrial emissions and air quality management. Journal of Environmental Management, 328, 116982. Retrieved from https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0301479723000149

Global Carbon Project. (2023). Global Carbon Budget 2023. Retrieved from https://www.globalcarbonproject.org/carbonbudget/23/highlights.htm

Huang, Y. (2022). China's energy transition: Is the world's largest polluter doing enough? Earth.org. Retrieved from https://earth.org/chinas-energy-transition-is-the-worlds-largest-polluter-doing-enough/

Zhang, Q., et al. (2023). Trends in China's air quality and their association with national energy policies. Environmental Science & Technology, 57(13), 5637-5646. Retrieved from https://pubs.acs.org/doi/abs/10.1021/acs.est.2c07814

Liu, J., & Diamond, J. (2023). China's environmental challenges: Pollution's impact on public health. Science Advances, 9(2), eabq1647. Retrieved from https://www.science.org/doi/full/10.1126/sciadv.abq1647

Li, M., et al. (2024). The economic cost of air pollution in China. Nature Sustainability, 7, 298-307. Retrieved from https://www.nature.com/articles/s41893-023-01226-9

Zhang, L., & Chen, Y. (2020). Evolution of environmental policy in China. Environmental Science & Policy, 104, 159-168. Retrieved from https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1462901119311997

Wang, S., et al. (2023). Impact assessment of China's Air Pollution Prevention and Control Action Plan. Environmental Pollution, 335, 122309. Retrieved from https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0269749123015768

Li, J., et al. (2024). Renewable energy in China: Policy, challenges, and prospects. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 191, 114470. Retrieved from https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1364032123010495

Zhang, Q., & He, K. (2022). China’s carbon markets: Challenges and opportunities. Nature Climate Change, 12, 401-403. Retrieved from https://www.nature.com/articles/s41558-022-01323-9

Liu, Y., & Wang, M. (2023). Enforcement of environmental policy in China: A study on regional disparities. Journal of Environmental Management, 335, 117580. Retrieved from https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0301479723002112

Huang, Y. (2022). Balancing economic growth and environmental sustainability in China. Earth.org. Retrieved from https://earth.org/balancing-economic-growth-and-environmental-sustainability-in-china/

Guan, D., et al. (2021). The socioeconomic drivers of China's primary PM2.5 emissions. Environmental Research Letters, 16(1), 014008. Retrieved from https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.1088/1748-9326/abd07b/meta

Zhang, X., & Xu, W. (2023). China's path to carbon neutrality: Policy analysis and future scenarios. Energy Policy, 173, 113349. Retrieved from https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0301421522005673

Li, Y., & Wu, Z. (2023). Environmental impacts of the Belt and Road Initiative: A review. Journal of Environmental Management, 340, 117980. Retrieved from https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0301479723007425

Zhang, H., et al. (2022). Deforestation and biodiversity loss under the Belt and Road Initiative. Conservation Letters, 15(5), e12895. Retrieved from https://conbio.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/conl.12895

Ascensão, F., et al. (2018). Environmental challenges for the Belt and Road Initiative. Nature Sustainability, 1(5), 206–209. Retrieved from https://www.nature.com/articles/s41893-018-0059-3

Eyler, B., & Weatherby, C. (2021). Mekong Dam Monitor: The Cost of Power. Stimson Center. Retrieved from https://www.stimson.org/2021/mekong-dam-monitor-the-cost-of-power/

Perera, R. (2020). Environmental impacts of the Hambantota Port Development Project. Marine Pollution Bulletin, 157, 111326. Retrieved from https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0025326X20304722

Hussain, M. & Khan, S. (2023). Environmental implications of the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 30, 12132-12146. Retrieved from https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11356-022-21909-5

Teo, H. C., et al. (2020). Environmental impacts of infrastructure development under the Belt and Road Initiative. Land Use Policy, 92, 104476. Retrieved from https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0264837719319459

WWF. (2017). The Belt and Road Initiative: WWF Recommendations and Spatial Analysis. World Wildlife Fund. Retrieved from https://wwf.panda.org/?316994/The-Belt-and-Road-Initiative-WWF-Recommendations-and-Spatial-Analysis

Greenpeace. (2023). Belt and Road Initiative: A Greenpeace assessment. Greenpeace International. Retrieved from https://www.greenpeace.org/international/publication/38483/belt-and-road-initiative-a-greenpeace-assessment/

WWF. (2021). The Belt and Road Initiative and its impact on biodiversity. World Wildlife Fund. Retrieved from https://wwf.panda.org/?364344/The-Belt-and-Road-Initiative-and-its-impact-on-biodiversity

Mahathir, M. (2018). Malaysia cancels China-backed rail project. Al Jazeera. Retrieved from https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2018/8/21/malaysia-cancels-china-backed-rail-project

Liu, J., & Diamond, J. (2020). China's Environment in a Globalizing World. Nature, 580, 23-25. Retrieved from https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-020-00998-x

Zhang, Q., et al. (2021). Greening the Belt and Road Initiative: An assessment of China's green development guidance. Environmental Science & Policy, 116, 128-136. Retrieved from https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1462901120313395

Gallagher, K. P., & Qi, G. (2020). China's Belt and Road Initiative and the global climate regime. Global Environmental Politics, 20(2), 39-60. Retrieved from https://direct.mit.edu/glep/article/20/2/39/96013/China-s-Belt-and-Road-Initiative-and-the-Global

Lee, Y. (2022). Debt-trap diplomacy: The fallacy of the Belt and Road Initiative. The Diplomat. Retrieved from https://thediplomat.com/2022/02/debt-trap-diplomacy-the-fallacy-of-the-belt-and-road-initiative/

Ascensão, F., et al. (2018). Environmental challenges for the Belt and Road Initiative. Nature Sustainability, 1(5), 206-209. Retrieved from https://www.nature.com/articles/s41893-018-0059-3