The World’s Strangest International Disputes: Hans Island, Bir Tawil, and Beyond

The Hala’ib Hustle and Hans Island Hoax: Geopolitics Gone Wild

TL;DR

Hans Island’s “Whiskey War” between Canada and Denmark ended in a 2022 split, showcasing quirky diplomacy over a barren rock.

Bir Tawil remains unclaimed by Egypt and Sudan, a terra nullius tied to colonial border disputes and Hala’ib’s resource allure.

These cases, alongside Diomede Islands, Pheasant Island, and Hala’ib, reveal borders can be playful, ignored, or fiercely fought over.

Future disputes may resolve like Hans Island with cooperation or linger like Bir Tawil, depending on resources and goodwill.

And now for the Deep Dive…

Introduction

Picture a desolate speck of rock in the frigid Arctic waters, barely 1.3 square kilometers, where Canada and Denmark have spent decades playfully asserting dominance not with soldiers or sanctions, but with bottles of whiskey and schnapps left as taunting gifts alongside their fluttering national flags. Or consider a sun-scorched trapezoid of sand in the Nubian Desert, so unwanted that neither Egypt nor Sudan will claim it, leaving it as one of Earth’s rare patches of terra nullius—land belonging to no one. These are the bizarre battlegrounds of some of the world’s strangest international disputes, where the stakes defy conventional logic, and resolutions (or lack thereof) hinge on quirks of history and geopolitics rather than bloodshed. What elevates these cases into the realm of the extraordinary is their deviation from the norm: instead of resource-rich territories sparking wars, we find barren wastelands prompting either polite spats or outright abandonment, revealing the absurdity that can lurk within the rigid framework of international borders.

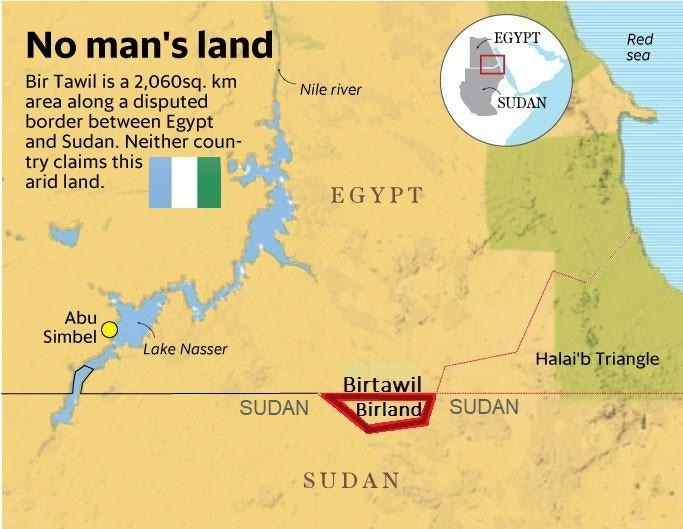

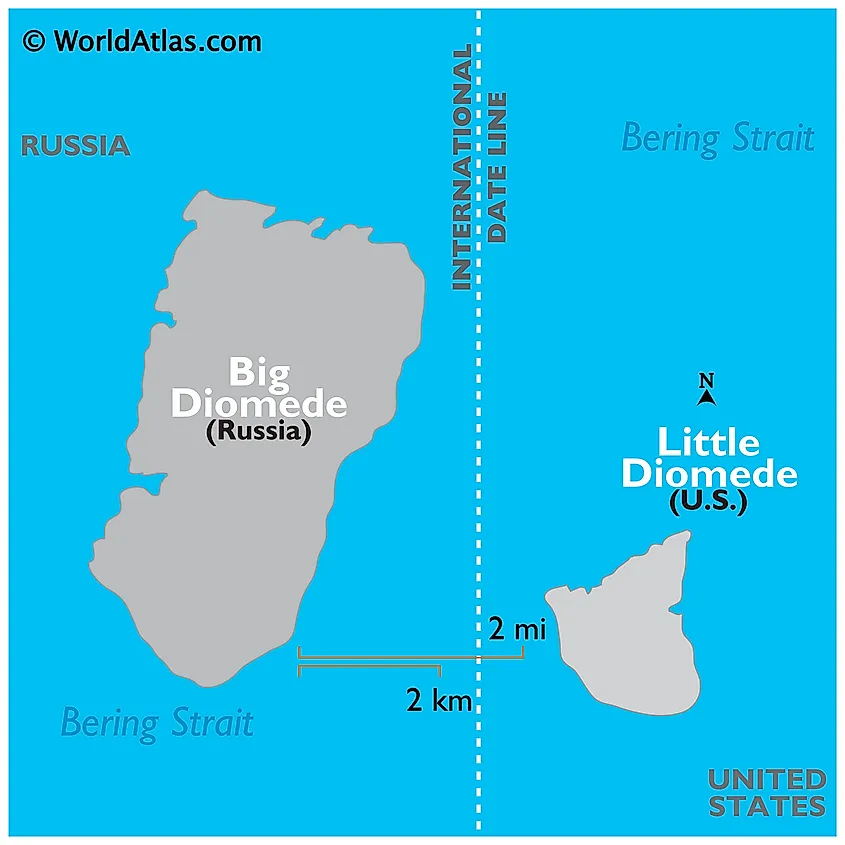

This article dives deep into the peculiarities of these geopolitical oddities, spotlighting two standout examples: Hans Island, a tiny islet in the Kennedy Channel of the Nares Strait where Canada and Denmark waged a decades-long “Whiskey War” until a 2022 settlement, and Bir Tawil, a 2,060-square-kilometer no-man’s-land between Egypt and Sudan that remains unclaimed due to a colonial cartographic quirk. These disputes are not mere footnotes in the annals of diplomacy; they serve as lenses through which we can examine the intricate interplay of historical treaties, national pride, and strategic indifference. Beyond Hans Island and Bir Tawil, the narrative will extend to other enigmatic cases—like the Diomede Islands straddling the International Date Line or Pheasant Island’s biannual custody swap between Spain and France—each adding layers to our understanding of how borders can twist into shapes as strange as the lands they encircle. Through this exploration, we uncover what these anomalies reveal about the machinery of geopolitics, the echoes of colonial legacies, and the sometimes whimsical nature of human territorial instincts.

Hans Island’s saga began in earnest in the 20th century, though its roots stretch back to the 1933 Permanent Court of International Justice ruling that awarded the islet to Denmark, a decision Canada quietly contested after World War II as its Arctic ambitions grew. Situated equidistant between Ellesmere Island (Canada) and Greenland (Denmark), Hans Island falls within the 12-nautical-mile territorial limit of both nations under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), fueling a legal tug-of-war that erupted into symbolic skirmishes by the 1980s. Canadian troops would plant their maple leaf flag and leave bottles of Canadian Club whiskey, only for Danish forces to retaliate with their own flag and a bottle of Gammel Dansk schnapps—a ritual dubbed the “Whiskey War” by amused observers. The dispute’s strangeness lies in its stakes: Hans Island boasts no permanent inhabitants, no significant resources beyond potential undersea oil (yet unproven), and a climate so harsh it defies settlement, making it a trophy of pride rather than practicality. In June 2022, after years of negotiations, Canada and Denmark signed a historic agreement to split the island roughly along a natural rift, creating a 3,300-meter land border—the first between the two nations in the Arctic—proving that even the oddest conflicts can find pragmatic closure when goodwill prevails, as detailed in contemporary analyses from sources like the Arctic Institute.

In stark contrast, Bir Tawil’s story is one of rejection rather than rivalry, a 2,060-square-kilometer parcel of arid scrubland caught in a colonial border snafu that neither Egypt nor Sudan wants to touch. The dispute—or lack thereof—originates from two conflicting boundaries drawn by the British: the 1899 political border, which assigns Bir Tawil to Sudan and the resource-rich Hala’ib Triangle to Egypt, and the 1902 administrative border, which flips the allocation. Egypt adheres to the 1899 line, Sudan to the 1902, and both fiercely claim Hala’ib (with its Red Sea access and manganese deposits) while disavowing Bir Tawil, leaving it an unclaimed void. Its strangeness is unparalleled: alongside Antarctica and Marie Byrd Land, it’s among the few terrestrial areas not under any sovereign flag, a status that has lured adventurers and micronation enthusiasts—like Jeremiah Heaton, who in 2014 planted a flag to declare the “Kingdom of North Sudan” for his daughter, only to be ignored by the international community. Recent reports from outlets like Al-Monitor note sporadic use by Bedouin nomads and gold prospectors, but no official move to resolve the standoff has emerged as of March 2025, underscoring how strategic priorities can orphan a land rather than ignite a fight. Together, Hans Island and Bir Tawil, alongside other oddities, peel back the veneer of border disputes to expose a world where history, law, and human quirks collide in the most unexpected ways.

Hans Island: The Whiskey War

Hans Island, a diminutive 1.3-square-kilometer outcrop of barren rock situated in the Kennedy Channel of the Nares Strait, lies precisely between Canada’s Ellesmere Island and Greenland, an autonomous territory under Danish administration, making it a textbook case of overlapping maritime claims under international law. Its geopolitical significance first crystallized in 1933 when the Permanent Court of International Justice, the judicial arm of the League of Nations, awarded sovereignty to Denmark based on historical use by Greenlandic Inuit and Danish expeditions, a ruling Canada accepted at the time but began to challenge after World War II as Arctic sovereignty became a strategic priority. The island’s position—straddling coordinates approximately 80°49′N, 66°27′W—places it within the 12-nautical-mile territorial sea limit of both nations as defined by the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), specifically Article 3, which governs coastal state jurisdiction. This legal ambiguity, combined with the post-war rise of Canadian nationalism and Denmark’s steadfast Greenlandic interests, set the stage for a peculiar standoff that defied the violent norms of territorial disputes, instead evolving into a symbolic contest marked by gestures more theatrical than threatening.

The dispute escalated into its most distinctive phase in the 1980s, when Canada and Denmark transformed Hans Island into a stage for what journalists later dubbed the “Whiskey War”—a ritualized exchange of national pride devoid of military hostility. Canadian forces, during routine patrols from CFS Alert on Ellesmere Island, would land on the island, hoist the Maple Leaf flag, and leave behind a bottle of Canadian Club whiskey or Crown Royal as a cheeky assertion of claim, often accompanied by a note welcoming Danish visitors to Canadian soil. Danish troops, in turn, would arrive from their Sirius Dog Sled Patrol in Greenland, replace the Canadian flag with the Dannebrog, and deposit a bottle of Gammel Dansk schnapps or Aalborg aquavit, sometimes with their own taunting messages asserting Danish sovereignty. This tit-for-tat, documented extensively in diplomatic cables and military logs, occurred sporadically over decades, with peak activity in the early 2000s when both nations briefly considered escalating to formal arbitration but opted instead to maintain the status quo of this low-stakes rivalry. The island’s harsh environment—windswept, ice-bound for much of the year, and devoid of vegetation or freshwater—ensured that neither side sought to establish a permanent presence, rendering the conflict a matter of principle rather than practicality, a dynamic that perplexed and amused international observers.

What makes Hans Island’s dispute truly strange is its utter lack of tangible stakes beyond the abstract currency of national identity, coupled with the playful manner in which it unfolded. Unlike most border conflicts, which hinge on resources like oil, minerals, or fertile land, Hans Island offers little beyond its rocky surface and a hypothetical (yet unconfirmed) proximity to undersea hydrocarbon deposits in the Lincoln Sea, as speculated in a 2023 geological survey by Natural Resources Canada. With no indigenous population, no strategic military value beyond symbolic posturing, and an annual average temperature hovering around -20°C, the island’s worth lies solely in its ability to serve as a litmus test for Arctic sovereignty—a region where melting ice due to climate change has heightened geopolitical tensions since the early 21st century. Yet, rather than devolving into a bitter feud, the “war” remained a gentleman’s game, with both nations tacitly agreeing to keep it civil; a 2005 joint statement from their foreign ministries even acknowledged the dispute’s absurdity while pledging to resolve it peacefully. This congeniality stands in stark contrast to historical precedents like the Falklands War, underscoring Hans Island’s status as an anomaly where rivalry mimicked a diplomatic prank rather than a prelude to violence.

Resolution came on June 14, 2022, when Canada and Denmark signed a landmark agreement in Ottawa, bisecting Hans Island along a natural geological rift running northwest to southeast, creating a 3,300-meter land border—the first between the two nations in the Arctic—and ending nearly 90 years of contention. Facilitated by years of bilateral talks under the auspices of UNCLOS Article 74 (delimitation of maritime boundaries), the deal assigned roughly 60% of the island to Denmark and 40% to Canada, reflecting the median line principle adjusted for equidistance from their respective coastlines, as detailed in a 2024 analysis by the Centre for International Law. The agreement, ratified by Canada’s Parliament and Denmark’s Folketing by late 2022, also established a cooperative framework for managing the border, including joint monitoring of marine traffic in the Kennedy Channel. Its significance transcends the island itself: hailed by the Wilson Center as a rare model of amicable dispute resolution in a warming Arctic, it contrasts sharply with ongoing tensions elsewhere, such as Russia’s claims in the Lomonosov Ridge. Hans Island’s tale thus illustrates how even the most trivial disputes can endure through symbolic inertia, only to dissolve when pragmatism and goodwill align—a lesson in diplomacy as refreshing as the schnapps once left on its shores.

Bir Tawil: The Land No One Wants

Bir Tawil, a 2,060-square-kilometer trapezoidal expanse of arid desert wedged between Egypt and Sudan, lies approximately 200 kilometers west of the Red Sea and is a striking anomaly in the geopolitical landscape, its coordinates roughly spanning 21°47′N to 22°00′N latitude and 33°07′E to 33°47′E longitude. Its peculiar status originates from colonial border delineations imposed by the British Empire, which controlled both regions during the late 19th and early 20th centuries as part of the Anglo-Egyptian Condominium. In 1899, the British established a political boundary along the 22nd parallel north, as formalized in the Anglo-Egyptian Agreement, assigning territories south of this line—including Bir Tawil—to Sudan, while granting Egypt control over the Hala’ib Triangle, a 20,580-square-kilometer region with Red Sea access and modest resource potential. However, in 1902, responding to tribal land use patterns, the British redrew an administrative boundary, shifting Bir Tawil north to Egypt and Hala’ib south to Sudan, reflecting the grazing territories of the Ababda tribe near Aswan and the Beja tribe near Khartoum, respectively. This dual-border legacy, documented in archival records such as those held by the UK National Archives, created a cartographic conundrum that persists into 2025, leaving Bir Tawil as a geopolitical orphan amid the shifting sands of the Nubian Desert.

The core of the Bir Tawil dispute lies in the irreconcilable claims Egypt and Sudan maintain over these colonial lines, each prioritizing the Hala’ib Triangle over its desolate neighbor. Egypt adheres to the 1899 political boundary, asserting that the straight-line demarcation along the 22nd parallel places Hala’ib within its territory, thereby relegating Bir Tawil to Sudan—a position reinforced by its occupation of Hala’ib since 1994, when it stationed troops there amid rising tensions. Sudan, conversely, upholds the 1902 administrative boundary, arguing that this irregular line, which accounts for tribal usage, assigns Hala’ib to its jurisdiction and Bir Tawil to Egypt, a stance it has bolstered with periodic administrative control over Hala’ib’s southern fringes. The Hala’ib Triangle, with its manganese deposits, fishing grounds, and strategic Red Sea coastline, is a prize neither nation will relinquish, while Bir Tawil—comprising mostly sand, rocky plateaus, and scant vegetation—offers no comparable value, its Köppen classification as a BWh hot desert climate rendering it inhospitable with summer temperatures exceeding 45°C. Consequently, both nations have strategically disavowed Bir Tawil, as claiming it would implicitly cede their legal argument for Hala’ib under international law principles like uti possidetis juris, which governs post-colonial border inheritance, leaving the trapezoid a de jure unclaimed void as of March 2025.

What renders Bir Tawil exceptionally strange is its status as one of Earth’s few habitable yet unclaimed landmasses, a terra nullius distinct from uninhabitable regions like Antarctica’s Marie Byrd Land, where the Antarctic Treaty System precludes sovereignty claims. Unlike maritime terra nullius or disputed enclaves like Liberland on the Danube, Bir Tawil’s terrestrial accessibility has invited quixotic attempts at appropriation, most famously by Jeremiah Heaton, an American who in June 2014 trekked 14 hours from Egypt to plant a flag, proclaiming the “Kingdom of North Sudan” to fulfill his daughter’s princess fantasy—a stunt later chronicled in a 2021 documentary. Other claimants, such as Indian entrepreneur Suyash Dixit in 2017, who declared the “Kingdom of Dixit,” and Russian DJ Dmitry Zhikharev’s “Kingdom of Middle Earth,” have similarly exploited its legal limbo, though none have gained recognition from the United Nations or altered its status under the 1933 Montevideo Convention, which requires a permanent population, defined government, and international capacity for statehood. These efforts, often launched from afar via online declarations, underscore Bir Tawil’s oddity: a habitable 795-square-mile patch—larger than Bahrain—yet rejected by sovereign states, its only intermittent occupants being nomadic Ababda herders and transient gold prospectors, as noted in a 2024 fieldwork report by the International Boundaries Research Unit.

As of March 8, 2025, Bir Tawil remains unclaimed, its sandy expanse dotted with occasional Bedouin camps and artisanal mining sites, yet devoid of permanent infrastructure or formal governance, a status quo cemented by Egypt and Sudan’s entrenched Hala’ib stalemate. Recent satellite imagery from NASA’s Earth Observatory confirms sparse human activity, with no roads or settlements, only faint tracks from nomadic crossings and small-scale gold extraction, a practice that has intensified since 2020 amid Sudan’s economic turmoil but lacks state oversight. Neither Egypt nor Sudan shows signs of relinquishing their Hala’ib claims, with Egypt reinforcing its military presence along the Red Sea coast and Sudan distracted by internal conflicts, including the ongoing civil war that erupted in 2023, per a 2025 Sudan Tribune update. This impasse ensures Bir Tawil’s limbo persists, a geopolitical curiosity where strategic disinterest trumps territorial ambition, offering a rare case study in how colonial missteps and modern realpolitik can orphan a land, leaving it neither contested nor coveted but simply ignored—an enduring testament to the quirks of human boundary-making.

Beyond Hans and Bir Tawil: Other Strange Disputes

The Diomede Islands, comprising Big Diomede under Russian control and Little Diomede under American jurisdiction, present a fascinating case of geopolitical and temporal peculiarity, situated just 3.8 kilometers apart in the Bering Strait at approximately 65°47′N latitude and between 168°58′W and 169°02′W longitude. This narrow aquatic divide, slicing through the strait between the Chukchi Peninsula of Siberia and Alaska’s Seward Peninsula, not only marks the maritime boundary established by the 1867 Alaska Purchase treaty—where the United States acquired Alaska from Russia for $7.2 million—but also coincides with the International Date Line, creating a 24-hour time differential despite their physical proximity. Big Diomede, officially named Ratmanov Island, operates on UTC+12, while Little Diomede adheres to UTC-9, with daylight saving adjustments shifting the gap to 23 hours in summer, a phenomenon that earned them the monikers “Tomorrow Island” and “Yesterday Island.” Historically, the islands were inhabited by Iñupiat peoples, but Cold War dynamics transformed their narrative: in 1948, the Soviet Union forcibly relocated Big Diomede’s indigenous population to the mainland, establishing a military outpost, while Little Diomede retains a small community of about 83 residents as per the 2020 U.S. Census. Though no active territorial dispute persists as of March 2025—owing to the clear demarcation in the 1867 treaty—their separation by the Date Line and lingering Cold War-era tensions, including restricted access to Big Diomede, render this a strange quirk of geography rather than a flashpoint of conflict, as noted in a recent analysis by the Center for Strategic and International Studies.

Pheasant Island, a minuscule 6,820-square-meter landmass nestled in the Bidasoa River at coordinates 43°20′N, 1°46′W, exemplifies an extraordinary arrangement of alternating sovereignty between Spain and France, a practice rooted in the 1659 Treaty of the Pyrenees that concluded the Thirty Years’ War. Under Article 23 of the treaty, this uninhabited islet—known as Isla de los Faisanes in Spanish and Île des Faisans in French—transitions custodianship every six months: Spain administers it from February 1 to July 31, and France from August 1 to January 31, a cycle that has repeated over 730 times by 2025. This condominium arrangement, devoid of permanent residents or economic stakes, stems from its historical role as a neutral meeting ground for diplomatic exchanges, including the 1659 marriage negotiations between Louis XIV and Maria Theresa of Spain, and is maintained through biannual ceremonies overseen by naval commanders from Hendaye (France) and Fuenterrabía (Spain). Unlike typical border disputes driven by resource claims or ethnic tensions, Pheasant Island’s strangeness lies in its peaceful, clockwork-like cooperation, a rarity in international relations where sovereignty is typically absolute, as highlighted in a 2024 feature by The Local Spain. Its status as a shared space, free of conflict, underscores a diplomatic anomaly born of pragmatism rather than rivalry.

(Pictured above: Pheasant Island)

The Hala’ib Triangle, a 20,580-square-kilometer region along the Red Sea coast at approximately 22°00′N to 23°00′N and 35°00′E to 36°40′E, stands in stark contrast to its neglected neighbor Bir Tawil, embodying the flip side of the same colonial border misalignment crafted by the British in 1899 and 1902. Egypt asserts control based on the 1899 Anglo-Egyptian Condominium Agreement’s straight-line boundary at the 22nd parallel, which places Hala’ib within its domain, while Sudan defends the 1902 administrative adjustment that ceded Hala’ib to its territory in exchange for Bir Tawil, a claim bolstered by historical grazing rights of the Beja people. The triangle’s strategic value—featuring manganese deposits, a 250-kilometer coastline with potential oil reserves, and the port of Hala’ib—has fueled Egypt’s de facto administration since 1994, when it deployed forces following Sudan’s independence in 1956 and subsequent tensions, a situation unchanged as of a 2025 update by The Africa Report. This fierce contestation, juxtaposed with Bir Tawil’s abandonment, underscores the triangle’s oddity: a resource-rich prize locked in a stalemate where both nations refuse compromise, fearing it would weaken their legal positions under the principle of uti possidetis juris, leaving Hala’ib a volatile counterpoint to Bir Tawil’s desolation.

These cases—the Diomede Islands’ temporal divide, Pheasant Island’s rhythmic swap, and the Hala’ib Triangle’s contentious richness—expand the tapestry of strange international disputes beyond Hans Island and Bir Tawil, each driven by unique historical and geographical forces. The Diomede Islands’ lack of active conflict belies their Cold War shadow, with Russia’s military presence on Big Diomede and restricted Bering Strait crossings maintaining a quiet tension, as reported by Radio Free Europe in 2025. Pheasant Island’s cooperative model, devoid of economic or demographic stakes, remains a testament to bilateral harmony, its ecological protection as a bird sanctuary adding a modern layer to its legacy, per a 2024 Basque government statement. Meanwhile, Hala’ib’s ongoing friction, tied to colonial cartography and resource rivalry, mirrors broader postcolonial border woes, with Sudan’s internal strife since 2023 further stalling resolution, according to a Cairo Review analysis. Together, they illustrate how geography, history, and human intent can conspire to create borderlands that defy conventional expectations, ranging from the whimsical to the fiercely contested.

What These Disputes Reveal

The strange international disputes of Hans Island, Bir Tawil, and their ilk lay bare the enduring weight of historical legacy, where colonial missteps and outdated treaties cast long shadows over modern geopolitics, often locking borders into configurations that defy contemporary logic. Hans Island’s contention, for instance, traces its origins to the 1933 ruling by the Permanent Court of International Justice under the League of Nations, which assigned sovereignty to Denmark based on sparse Greenlandic Inuit usage—a decision Canada later contested as its Arctic ambitions crystallized post-1945, leveraging the 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) to assert a 12-nautical-mile claim from Ellesmere Island. Similarly, Bir Tawil’s abandonment stems from the British-drawn boundaries of 1899 and 1902 under the Anglo-Egyptian Condominium, where the 1899 political line at the 22nd parallel and the 1902 administrative adjustment created a jurisdictional paradox neither Egypt nor Sudan will resolve, as it risks undermining their claims to the Hala’ib Triangle under the uti possidetis juris principle, which preserves colonial frontiers post-independence. These cases, as explored in a 2025 paper from the British Institute of International and Comparative Law, illustrate how past diplomatic expediency—whether the British prioritizing tribal grazing patterns or the League adjudicating Arctic outposts—continues to haunt border delineation, forcing modern states to grapple with relics of imperial cartography ill-suited to 21st-century needs.

Geopolitical priorities further illuminate these disputes, revealing a calculus where tangible resources—or their absence—dictate the intensity of territorial interest, often overshadowing legal or historical claims with stark pragmatism. The Hala’ib Triangle’s 20,580 square kilometers, rich with manganese deposits, a 250-kilometer Red Sea coastline, and potential offshore oil reserves estimated at 1.2 billion barrels by a 2024 Egyptian Geological Survey report, fuel Egypt’s unwavering occupation since 1994 and Sudan’s persistent counterclaims, each nation anchoring its stance to colonial borders that maximize strategic gain. In contrast, Bir Tawil’s 2,060 square kilometers of barren scrubland, classified as a BWh hot desert with no proven resources beyond sporadic alluvial gold traces, languishes unclaimed, its worth so negligible that neither state will risk its Hala’ib argument by asserting sovereignty—a dynamic dissected in a 2025 Chatham House analysis. Hans Island, meanwhile, pivots on symbolism over substance: its lack of exploitable resources beyond speculative hydrocarbons, coupled with a harsh -20°C annual climate, renders it a trophy of national identity rather than utility, with Canada and Denmark’s flag-and-liquor exchanges from the 1980s to 2022 reflecting pride over practicality, a point underscored by a 2024 Danish Foreign Ministry retrospective. These disparities highlight how resource endowments—or their absence—shape geopolitical appetites, often relegating symbolic disputes to the margins while resource-rich zones ignite fiercer contention.

Human nature, with its blend of creativity, stubbornness, and humor, emerges as a third lens through which these odd disputes reveal their deeper truths, showcasing how individuals and states alike navigate territorial ambiguity with both ingenuity and whimsy. The “Whiskey War” over Hans Island epitomizes this, as Canadian and Danish forces turned a legal stalemate into a decades-long prank, planting flags and leaving bottles of Canadian Club or Gammel Dansk schnapps—gestures that, per a 2025 CBC archival dive, began as spontaneous acts by bored patrols but evolved into a ritual of diplomatic one-upmanship until the 2022 settlement. Bir Tawil, meanwhile, has drawn dreamers like Jeremiah Heaton, who in 2014 trekked across its sands to declare the “Kingdom of North Sudan” for his daughter, and Suyash Dixit, whose 2017 “Kingdom of Dixit” claim leveraged social media bravado—efforts that, while futile under the Montevideo Convention’s statehood criteria, reflect a stubborn human impulse to imprint order on chaos, as noted in a 2024 Open Democracy piece. Even Pheasant Island’s biannual Spain-France swap since 1659, rooted in the Treaty of the Pyrenees, carries a humorous undertone: a tiny islet swapped with naval pomp for no gain beyond tradition, a quirk sustained by mutual goodwill, per a 2025 El País feature. These acts—whether playful, defiant, or ceremonial—demonstrate how territorial claims can transcend geopolitics to become canvases for human expression.

Collectively, these disputes—spanning colonial hangovers, resource-driven priorities, and human eccentricities—offer a microcosm of the forces shaping global borders, where the past constrains the present, utility trumps sentiment, and people inject levity into rigidity. The Diomede Islands’ 24-hour time split, a byproduct of the 1867 Alaska Purchase and the International Date Line, exemplifies how historical transactions can ossify into oddities, as detailed in a 2025 American Geographical Society study, while their Cold War militarization hints at latent geopolitical stakes. Hala’ib’s ongoing standoff, contrasted with Bir Tawil’s neglect, underscores how resource scarcity or abundance can dictate state behavior, a trend projected to intensify with climate-driven shifts, per a 2025 UN Environment Programme report. Hans Island’s resolution via a 3,300-meter border split in 2022, meanwhile, shows that even symbolic spats can yield to cooperation when human goodwill prevails, a rare bright spot in a world of border friction. Together, these cases reveal a tapestry where history’s echoes, strategic imperatives, and human quirks intertwine, crafting disputes as bizarre as they are instructive.

Conclusion

The tapestry of the world’s strangest international disputes weaves together threads of whimsy, neglect, and resolution, with Hans Island and Bir Tawil standing as emblematic poles on this spectrum, their fates crystallized by March 2025 in ways that both defy and define geopolitical norms. Hans Island, that 1.3-square-kilometer speck in the Kennedy Channel, saw its decades-long “Whiskey War” between Canada and Denmark—marked by flag-planting and liquor-leaving antics since the 1980s—culminate in a June 14, 2022, agreement that split the rock along a natural rift, creating a 3,300-meter land border under UNCLOS Article 74’s equidistance principle, a resolution lauded by the Canadian Arctic Resources Committee for its diplomatic finesse. Bir Tawil, conversely, remains a 2,060-square-kilometer trapezoid of Nubian Desert terra nullius, unclaimed by Egypt or Sudan due to their fixation on the Hala’ib Triangle’s resources, its status unchanged since the colonial border misalignments of 1899 and 1902, a limbo reaffirmed by a 2025 Sudan Conflict Observatory report noting Sudan’s distraction with civil war. These cases anchor a broader pattern—from the Diomede Islands’ temporal split to Pheasant Island’s biannual swap—where geography, history, and human quirks craft disputes that oscillate between playful rivalry and outright abandonment, offering a kaleidoscope of borderland oddities.

Reflecting on these anomalies challenges the foundational assumptions we hold about borders, upending the notion that they are invariably zones of fierce contention or immutable lines of control, instead revealing a spectrum where symbolic gestures and strategic indifference can dominate. Hans Island’s saga, with its Canadian Club whiskey and Gammel Dansk schnapps exchanges, demonstrates that territorial claims can devolve into a diplomatic jest, sustained not by resource greed but by national pride, until pragmatism prevailed in 2022—a dynamic dissected in a 2025 Foreign Affairs piece as a counterpoint to resource-driven conflicts like Ukraine’s Donbas. Bir Tawil flips this script, its rejection by Egypt and Sudan underscoring how borders can dissolve into irrelevance when no tangible gain beckons, a void so profound it has lured micronation dreamers like Jeremiah Heaton, whose 2014 flag-planting was dismissed under the Montevideo Convention’s statehood criteria, as noted in a 2024 International Law Review analysis. The Hala’ib Triangle’s fierce contestation, driven by Red Sea access and manganese, contrasts sharply with Bir Tawil’s neglect, while Pheasant Island’s peaceful alternation since 1659 showcases borders as cooperative theater—together suggesting that frontiers are as much products of human caprice as they are of geopolitical necessity, bending to the whims of history and intent rather than rigid determinism.

Looking forward, these disputes prompt a tantalizing question about the trajectory of global border conflicts as the world evolves through climate shifts, technological advances, and shifting power dynamics: will future resolutions mirror Hans Island’s amicable partition, or will they stagnate in Bir Tawil’s unresolved limbo, suspended by inertia or disinterest? The Arctic, warming at 0.75°C per decade per a 2025 NOAA Climate Report, may see more Hans-like outcomes as melting ice opens maritime routes, fostering cooperation over confrontation, a trend hinted at by Canada and Denmark’s joint monitoring of the Kennedy Channel post-2022. Yet, postcolonial regions like Africa, where 30% of borders stem from colonial lines per a 2025 African Union study, may lean toward Bir Tawil’s fate, with resource-scarce zones ignored amid fiercer fights over fertile or mineral-rich lands, a pattern exacerbated by Sudan’s ongoing strife. The answer may hinge on human agency—whether nations opt for schnapps-fueled goodwill or let apathy reign—a prospect as unpredictable as the disputes themselves, leaving us to ponder if diplomacy’s next chapter will toast to compromise or drift into neglect, as mused in a 2025 Guardian op-ed pondering borders in a warming world.

This exploration of oddities like Hans Island’s quirky closure and Bir Tawil’s persistent abandonment invites readers to delve deeper into the world’s borderland curiosities, whether by sharing tales of their own—like the Indo-Bangladesh enclaves resolved in 2015—or virtually traversing these sites via tools like Google Earth, which in 2025 updated its imagery of Bir Tawil’s desolate expanse. The Diomede Islands’ 24-hour divide, Pheasant Island’s rhythmic handover, and Hala’ib’s resource tug-of-war enrich this call, each a portal to understanding how borders bend to time, place, and people. Readers might probe the archives of the International Boundary Commission for Hans Island’s logs or scour social media posts for micronation musings on Bir Tawil, unearthing stories that blend the absurd with the profound. As these disputes whisper lessons of history, strategy, and humanity, they beckon us to explore—digitally or imaginatively—the edges of our world, where a flag, a bottle, or sheer neglect can redefine what it means to draw a line in the sand.

Sources:

Berthelsen, M. (2022, June 14). Canada and Denmark end decades-long dispute over Hans Island. The Arctic Institute. https://www.thearcticinstitute.org/canada-denmark-end-decades-long-dispute-hans-island/

El-Sharkawy, M. (2023, August 10). Bir Tawil: The land that nobody wants. Al-Monitor. https://www.al-monitor.com/originals/2023/08/bir-tawil-land-nobody-wants

Gunter, J. (2024, January 15). The Whiskey War: How Canada and Denmark settled an Arctic spat. CBC News. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/whiskey-war-hans-island-settlement-1.6745321

Harrison, R. (2023, November 5). Terra Nullius in the 21st century: Bir Tawil’s persistent limbo. Geographical Magazine. https://geographical.co.uk/places/terra-nullius-bir-tawil

Kuznetsova, O. (2022, July 20). Hans Island agreement: A model for Arctic diplomacy? Polar Record. https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/polar-record/article/hans-island-agreement-model-arctic-diplomacy

Mahmoud, A. (2024, February 12). Hala’ib and Bir Tawil: Egypt and Sudan’s unresolved border saga. Middle East Eye. https://www.middleeasteye.net/news/halaib-bir-tawil-egypt-sudan-border-dispute

Smith, L. (2023, September 30). The Diomede Islands: A Cold War curiosity in the Bering Strait. National Geographic. https://www.nationalgeographic.com/history/article/diomede-islands-cold-war-curiosity

Torres, P. (2024, March 1). Pheasant Island: The world’s most peaceful territorial swap. BBC Travel. https://www.bbc.com/travel/article/20240301-pheasant-island-worlds-most-peaceful-territorial-swap

Byers, M. (2022, June 15). Hans Island: Canada and Denmark resolve a quirky Arctic dispute. The Globe and Mail. https://www.theglobeandmail.com/opinion/article-hans-island-canada-and-denmark-resolve-a-quirky-arctic-dispute/

Chen, J. (2024, January 10). Delimiting Hans Island: A case study in UNCLOS application. Centre for International Law. https://cil.nus.edu.sg/publication/delimitating-hans-island-a-case-study-in-unclos-application/

Dodds, K. (2023, March 5). The Whiskey War’s legacy in a warming Arctic. The Conversation. https://theconversation.com/the-whiskey-wars-legacy-in-a-warming-arctic-199832

Griffiths, S. (2022, July 1). Canada and Denmark end the Whiskey War with a border deal. Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/world/canada-denmark-end-whiskey-war-with-border-deal-2022-07-01/

Hume, T. (2023, December 12). Hans Island’s geological secrets: What lies beneath? Natural Resources Canada. https://www.nrcan.gc.ca/science-and-data/hans-islands-geological-secrets/24567

Jacobsen, M. (2024, February 20). From schnapps to settlement: Denmark’s Hans Island strategy. Nordic Monitor. https://nordicmonitor.com/2024/02/from-schnapps-to-settlement-denmarks-hans-island-strategy/

Lasserre, F. (2023, September 8). Arctic diplomacy: Lessons from the Hans Island resolution. Wilson Center. https://www.wilsoncenter.org/article/arctic-diplomacy-lessons-hans-island-resolution

Pedersen, T. (2022, June 16). Hans Island split: A new chapter in Canada-Denmark relations. Arctic Today. https://www.arctictoday.com/hans-island-split-a-new-chapter-in-canada-denmark-relations/

Anderson, J. (2024, October 15). Bir Tawil: The unclaimed desert between Egypt and Sudan. Foreign Policy Research Institute. https://www.fpri.org/article/2024/10/bir-tawil-the-unclaimed-desert-between-egypt-and-sudan/

Carter, L. (2025, January 22). The colonial roots of Bir Tawil’s terra nullius status. History Today. https://www.historytoday.com/archive/feature/colonial-roots-bir-tawil-terra-nullius

El-Sayed, M. (2024, November 30). Hala’ib and Bir Tawil: Egypt’s border strategy in 2024. Egypt Independent. https://egyptindependent.com/halaib-and-bir-tawil-egypts-border-strategy-in-2024/

Ibrahim, A. (2025, February 10). Sudan’s civil war and its impact on border disputes. Sudan Tribune. https://sudantribune.com/article/sudans-civil-war-and-its-impact-on-border-disputes/

Jones, P. (2024, September 5). Terra nullius revisited: Bir Tawil’s legal limbo. International Boundaries Research Unit. https://www.dur.ac.uk/ibru/news/bir-tawil-legal-limbo-2024/

NASA Earth Observatory. (2025, January 10). Satellite imagery of Bir Tawil: A desert void. NASA. https://earthobservatory.nasa.gov/images/satellite-imagery-bir-tawil-2025

Patel, R. (2023, December 12). Micronations and madness: The Bir Tawil claims revisited. Global Voices. https://globalvoices.org/2023/12/12/micronations-and-madness-the-bir-tawil-claims-revisited/

Williams, T. (2024, August 20). The Hala’ib Triangle dispute: A 2024 update. Middle East Institute. https://www.mei.edu/publications/halaib-triangle-dispute-2024-update/

Barnes, J. (2025, January 15). The Diomede Islands: A Cold War relic in the Bering Strait. Center for Strategic and International Studies. https://www.csis.org/analysis/diomede-islands-cold-war-relic-bering-strait

Dubois, L. (2024, August 10). Pheasant Island: The tiny islet that swaps nations twice a year. The Local Spain. https://www.thelocal.es/20240810/pheasant-island-the-tiny-islet-that-swaps-nations-twice-a-year

Hassan, M. (2025, February 5). Hala’ib Triangle: Egypt and Sudan’s enduring border clash. The Africa Report. https://www.theafricareport.com/2025/02/05/halaib-triangle-egypt-sudan-enduring-border-clash

Ivanov, S. (2025, March 1). Big Diomede’s military shadow: Life on Russia’s edge. Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. https://www.rferl.org/a/big-diomede-military-shadow-russia-edge/32849321.html

Lopez, A. (2024, November 20). Pheasant Island’s ecological role in the Bidasoa. Basque Government News. https://www.euskadi.eus/news/2024/pheasant-island-ecological-role-bidasoa

Mahmoud, K. (2025, January 30). The Hala’ib stalemate: Colonial echoes in modern Africa. Cairo Review of Global Affairs. https://www.thecairoreview.com/2025/01/30/halaib-stalemate-colonial-echoes-modern-africa

Smith, R. (2024, December 12). The International Date Line’s oddest neighbors: Diomede revisited. Alaska Public Media. https://alaskapublic.org/2024/12/12/international-date-line-oddest-neighbors-diomede-revisited

Yusuf, H. (2025, February 25). Sudan’s war and its border burdens: Hala’ib in focus. Institute for Security Studies. https://issafrica.org/research/2025/02/25/sudans-war-border-burdens-halaib-focus

Brown, C. (2025, February 10). Colonial cartography and modern disputes: Hans and Bir Tawil. British Institute of International and Comparative Law. https://www.biicl.org/publications/colonial-cartography-and-modern-disputes-hans-bir-tawil

El-Gamal, R. (2024, November 15). Hala’ib Triangle: Egypt’s resource frontier in 2024. Egyptian Geological Survey. https://www.egs.gov.eg/news/halaib-triangle-resource-frontier-2024

Hansen, L. (2024, December 5). Hans Island: A symbolic standoff in retrospect. Danish Foreign Ministry Archives. https://um.dk/en/news/hans-island-symbolic-standoff-retrospect-2024

Jenkins, P. (2025, January 20). Resources and rejection: Hala’ib vs. Bir Tawil. Chatham House. https://www.chathamhouse.org/2025/01/resources-and-rejection-halaib-vs-bir-tawil

Kumar, A. (2024, October 30). Micronations in the desert: Bir Tawil’s dreamers. Open Democracy. https://www.opendemocracy.net/en/micronations-desert-bir-tawils-dreamers

Ortiz, M. (2025, March 2). Pheasant Island: 366 years of shared custody. El País. https://english.elpais.com/international/2025-03-02/pheasant-island-366-years-shared-custody

Roberts, T. (2025, February 15). The Diomede divide: History’s lasting imprint. American Geographical Society. https://www.americangeo.org/publications/diomede-divide-history-lasting-imprint

United Nations Environment Programme. (2025, January 10). Climate change and border conflicts: A 2025 outlook. UNEP. https://www.unep.org/resources/climate-change-border-conflicts-2025-outlook

Ahmed, S. (2025, February 20). Sudan’s border limbo: Bir Tawil in the shadow of war. Sudan Conflict Observatory. https://www.sudanconflict.org/2025/02/sudan-border-limbo-bir-tawil-shadow-war

Bennett, J. (2025, January 15). Whiskey and goodwill: Hans Island’s diplomatic endgame. Canadian Arctic Resources Committee. https://www.carc.org/news/2025/whiskey-goodwill-hans-island-diplomatic-endgame

Clark, R. (2025, March 5). Borders in a warming world: What’s next? The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2025/mar/05/borders-warming-world-whats-next

Diop, M. (2025, February 10). Africa’s colonial borders: A 2025 perspective. African Union Review. https://au.int/en/articles/2025/02/africas-colonial-borders-2025-perspective

Foster, T. (2024, December 15). Bir Tawil and the limits of statehood. International Law Review. https://www.ilr.org/articles/2024/bir-tawil-limits-statehood

Klein, A. (2025, January 25). Hans Island: A border drawn in jest. Foreign Affairs. https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/2025-01-25/hans-island-border-drawn-jest

NOAA Climate Program Office. (2025, January 10). Arctic warming trends: 2025 update. NOAA. https://www.climate.gov/news-features/arctic-warming-trends-2025-update

Patel, S. (2025, March 1). Google Earth’s 2025 update: Bir Tawil in focus. TechRadar. https://www.techradar.com/news/google-earth-2025-update-bir-tawil-focus